Sareeta Amrute: Hi everybody. Welcome to Data & Society. My name is Sareeta Amrute. I’m the Director of Research here. It’s my sincere pleasure and honor to welcome you to data and Society for this discussion inspired by Mary Gray and Siddharth Suri’s recently-released book Ghost Work: How To Stop Silicon Valley From Building a New Global Underclass.

Mary Gray is Senior Researcher at Microsoft Research and Fellow at Harvard University’s Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society. Mary also maintains a faculty position in the School of Informatics, Computing, & Engineering, with affiliations in anthropology, gender studies, and the Media School at Indiana University. Her research looks at how technology access, material conditions, and everyday uses of media transform people’s lives. And today she’ll be talking to us about her latest book, written with Siddharth Suri who’s based in Seattle. Take it away Mary.

Mary L. Gray: Thank you. Thank you everyone for coming out. And I see some familiar faces and I just really want to voice my appreciation for all the support I’ve had over the years doing this work. First and foremost to my coauthor Sid Suri, but to all the workers who have given their time and let us into their lives to learn about their experiences. This work wouldn’t be possible without the time that they’ve given to us.

So with that I wanted to start by giving you a sense of where this work came from. And for me, I was thinking about my own research questions before coming to Microsoft Research. Most of them circled around the question of how do we become more or less seen? How are we known and valued as people? And what role do technologies play in that? And much of the heralding of the Internet was that we’re going to become more visible. We’re going to be able to speak our truth, hear all voices. And much of my grounding in anthropology and critical media studies brings me to the question of how so? When is that not true? And what are the conditions under which people make that more or less true?

So, I come to this project with that background. And in many ways What I’m hoping to do is incite you to care about this world of work that is more or less seen, known, and valued, depending on where you are in this universe. It really started with coming to Microsoft Research and asking a basic question about how artificial intelligence is made. I had no idea.

And so when I started asking computer scientists and engineers in my lab what goes into developing algorithms and the models that are built to be able to advance artificial intelligence, it turns out that there are a lot of people involved in that work outside of the coders and the engineers and computer scientists that are theorizing these technological innovations. It’s a lot of people who are effectively cleaning and managing data, the training data that become the models for building algorithms out. And there isn’t a case of any artificial intelligence that exists that doesn’t depend at some point in someone touching that data, curating that data, and taking something that’s otherwise kind of structuralist nonsense and putting it into some structured sense that a computational process could then model and learn from.

So the goal of this book, if there’s nothing else you take from this book, is to understand that artificial intelligence always has human hands in it. That we are benefiting from a lot of people contributing to advancing these technologies. Even in cases where we might fully automate one process along the way, particularly as its impact or its application to a domain it wasn’t expected to enter. Say language, like text translation that’s done in real time. If you’re a speaker of multiple languages and you’re code switching, odds are pretty good that the AI isn’t going to be able to keep up with you. So look at those cases where you then have to bring people back into the mix to be able to develop a model that would be able to capture what kind of exchange is happening.

That’s really the beginning of this book, is to understand who are the people who are doing all of this work. And it turns out that when you ask computer scientists and engineers, often their responses are, “I don’t really know.” I’ve never really met these people. The beauty of this technology is that I don’t have to meet them. And I say that now with all seriousness. The sense is that this is a technological innovation often called “human computation” or “crowdsourcing.” The technique of being able to thread a person into a moment of judgment where you need a person to be able to evaluate or decide something that a computational process can’t quite figure out?, bringing that person into that moment, that judgment, and then threading them into a computational process, an automated process so that you can carry on with an output.

So, we’re somewhat familiar with some of the applications. They’re are little bit visible to you today. This is an iceberg. Most of you are familiar perhaps with your Uber driver. You’ve met them. Maybe you’ve chatted with them. You might be familiar with other platform services, on-demand services, that effectively are using the same technology of human computation to match a person who’s able to deliver a service through a mix of application programming interfaces that calls that person to the job, whatever it might be. Whether it’s to pick you up at the airport, or to pick up some food and bring it to your door. Or if it’s a content moderator.

And I think what’s fascinating is two years ago if I’d said the phrase “content moderator” or “content moderation,” I would’ve just gotten blank looks. How many of you know what content moderation is today? It turns out they’re doing an incredibly important job. They are people who effectively curate, look at pieces of text and images that are beyond the capacity of any computational process to analyze and evaluate and say, “Ah. That’s pornography.” Or that’s spam versus someone sharing information.

So it turns out that we’re not that far along in being able to evaluate text and images to figure out is that content that should or should not be there. You could say anything that’s hard for a human to evaluate and decide, “Is that misinformation or just a fact that I’m not familiar with yet?” the odds are very good a computational process isn’t even close to being able to figure that out. If it’s hard for a person to figure out it’s going to be intractably, a technically hard process for computation to model. You have to have really certain this or that, yes or no, to build code with accuracy to be able to automate something.

So again, take away how much this world that’s completely dependent on having people at a moment of judgment enter the scene, like content moderation, and then look below that surface. And that surface below that iceberg, that is this spiraling, growing, expansive world of services that effectively are building to keep a person in a computational loop. Because it turns out it’s much more efficient and effective to be able to match a person to a task like captioning and translation, or a task that might be image tagging for a new set of images that you’re trying to evaluate, whether it’s for training AI or that you want to do a marketing project. In all of those cases, all of these businesses that’re probably unfamiliar to you that are on this slide, are quickly making the best of a business model that brings contract-driven, task-oriented work to people mostly doing work in their homes, or if they’re in a setting they’re covered by what are called vendor management systems. And again, they’re people that you will never meet as an end consumer, but that you benefit from every day.

So when I’m asking engineers and computer scientists about this work of human computation and the role of people in the loop, it turns out that most of these businesses are effectively doing what these engineers are doing, which is bringing people in as quickly as they can and then moving on to the next project. They’re not asking who are these people? Under what conditions might be be working? And in most cases they’re working on contract for that specific task itself. So the moment of engagement might not last more than a few minutes at best. So it’s a pretty kaleidoscopic world.

So, at Microsoft Research I feel incredibly lucky to be around people who do reflect on this question of what are they building for the rest of the world. And in many cases when I meet a group of people who are saying, “I don’t really know who are the workers who are here,” there’s at least a subset of those folks who will say, “I don’t exactly know but you know, the technology really keeps me at a distance.” And then there was a third set that would answer fairly regularly, “I don’t know and I don’t know if I want to know.”

And as you can imagine, for any anthropologists in the room that’s just…that’s…you really want to pursue that question. What makes somebody uncomfortable about knowing who is on the other side of a screen? What makes it seem an intractably, socially-uncomfortable question to find out about their work conditions?

So when I met Sid Suri, he was really one of the first people who genuinely coming out of computer science wanted to not only know what work conditions people might be engaging but what their lives were like. And so we started on the journey, and I don’t use that word lightly. It took us five years to develop a methodology for being able to bring the value of qualitative critical work that engages people in their everyday lives and figure out where you could integrate measurement and computational analyses to build out a picture of this world of work.

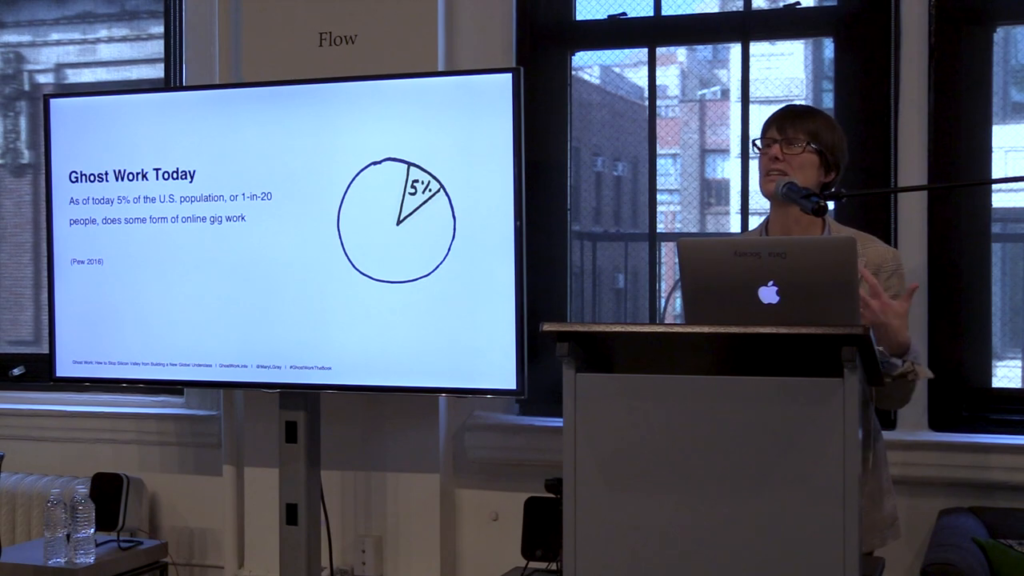

So, often will get this question of well, how big is this market? Underneath that question is often people who feel like why should we bother caring? This is work that’s going to be automated any day. If you buy the beginning premise of this book, and I hope you do, this work isn’t going away. The tasks will change. But in fact we’re building towards a world of a service industry, information services, knowledge work, that isn’t a niche job. This is the dismantlement of full-time employment. The dismantlement of full-time employment for anyone who does creative work.

So we might not be able to see how large that market is. Arguably we’ve never done a head count. There is no effective way to do a worker census of an environment that is by design distributed, global, and often doesn’t have a category of work that people would recognize and resonate with where they could say, “Yeah, that’s me. I do that work.” So this is both a world in which our old categories of “what job do you do” is being blown apart. And, it’s a world in which we don’t have any mechanisms for tracking and holding accountable the supply chain that’s going into this world of work.

But let’s take some guesses here. And some of this is drawing on economics and the secondary literature about the possible size of this market. Right now we know that there’s about an estimate of about 5% of the US population alone, according to Pew, that’s doing some form of online work. So at least in part, the work is sourced, scheduled, managed, shipped, and built through an application programming interface (an API) and the Internet; 5%. That doesn’t necessarily mean they’re doing their entire job online. It means that a form of income that’s important to them is coming from one of these jobs.

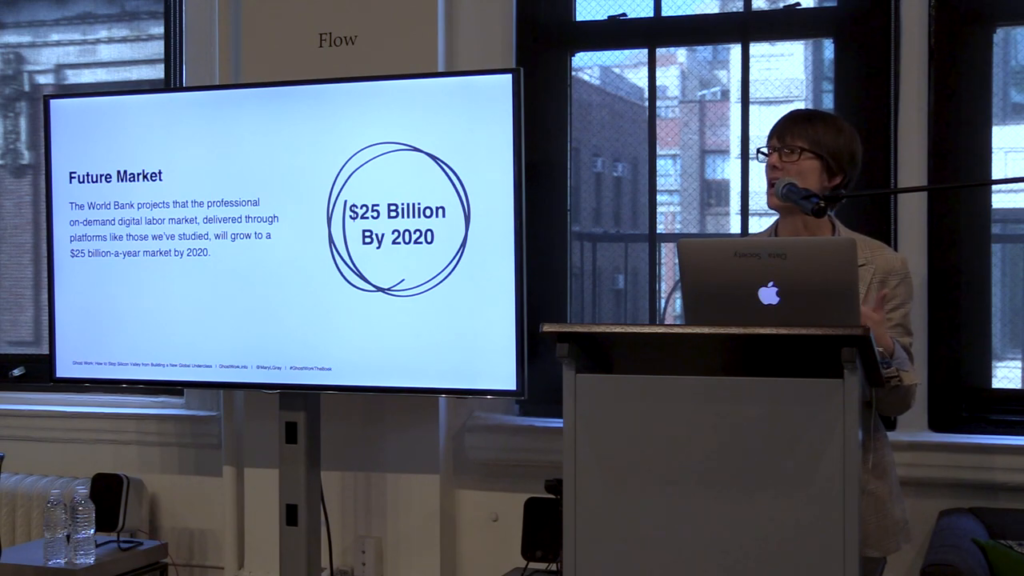

Now this is really striking if you take into consideration we’ve only had the possibility of making an income from this form of work for about a decade. So to have 5% of the US population already doing this work, start thinking through the size of this market, the growth of this market.

And if that’s not quite enough, think about how large the global market for the businesses generating value will be by next year. It’s a $25 billion dollar industry already. And that’s not a small number if you think about how it compares to other industries that are fairly mundane. So that iceberg that I showed you, all of those businesses that are spinning up below the surface of our visibility as consumers, is building an incredible amount of economic value that up to this point doesn’t seem to be moving to the other side of the screen, to the workers themselves who are doing the work.

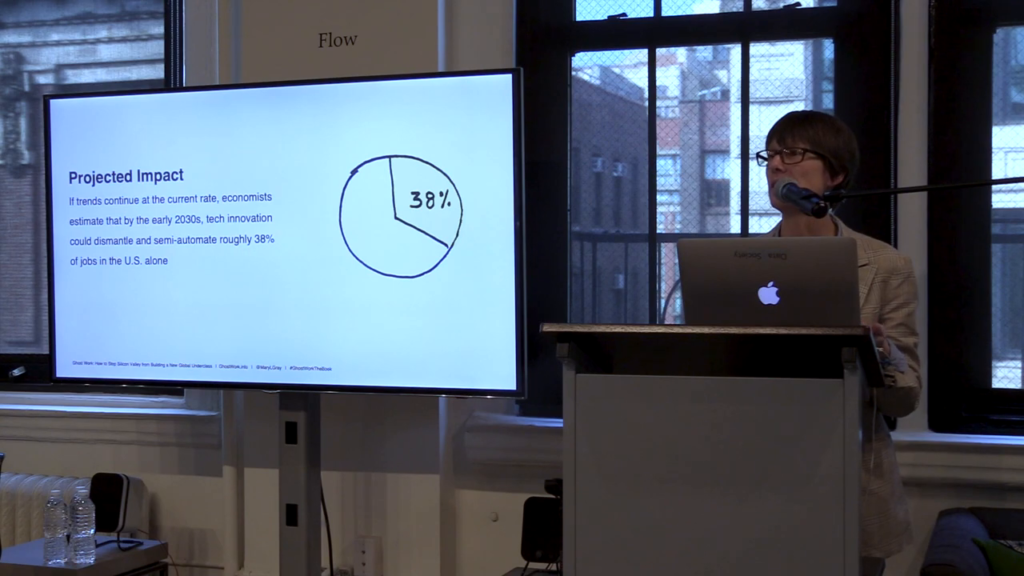

Another projection here of thinking about the implications of dismantling employment is to imagine this is not the displacement or the full automation of occupations and work. It’s the semi-automation of work and being able to taskify it that is the target of most of these industries and the technologies that companies are building. Everybody would like to figure out how to break down things like scheduling, managing any sorts of appointments, any of your workflow. Figuring out how to break that down and turn it into a task that you can hand off to someone else so that you can up whatever it is that is your main point of view or value, right. That this is again the object of most of the industry on building out the technologies. At the rate we’re going, we’re looking at 38% of jobs within the US moving to being semi-automated by the 2030s.

Now, that might sound like a shocking number but let’s just make it mundane. That means taking most of office work, knowledge work, information services, and turning it into contract work. That’s already happened, in a lot of places. So it’s not as though this is so futuristic. And in many ways the goal of this book is to say it is not too late to redefine what this world looks like. We’re really just at the beginning, but note that it’s moving quickly.

So the kinds of work that this entails… Again, because you can’t see it it’s often really hard to describe. It’s everything from editing, copy editing, content curation. If anybody participates in these kinds of jobs, you might see yourselves in these these tasks. Taking surveys, marketing design, any sort of graphic design. Any sort of data entry. And labeling, which is a pretty labor-intensive, cognitively-hard job. If you’re constantly looking at again, data that’s coming in that scraped from somewhere with not a lot of context and you’re trying to figure out what would you call this material? Analyzing somebody’s attitude about a product; how would you assess that attitude? It’s actually pretty challenging work. And it goes very quickly, kind of task by task.

We were studying very specific companies. I’m going to just go through a bit of the methodology that we used. But we were looking at companies that generate sales leads. So you can scrape the Web and get an idea of who your contact person might be if you sell air conditioners. But you’re going to do much better doing your sales if you know who you should call in that office. Turns out generating sales leads, that’s a particular kind of on-demand ghost work. Being able to take what is otherwise just a web scrape of people’s contact information, and curating that list and figuring out who should I contact, and then handing it over to a business that wants the best contacts. That’s a very specific vertical within this industry.

And then translation. TED has one of the largest open translation projects that was the beginning of a volunteer community invested in making videos available for hard of hearing communities and for linguistic diversity. And it was the the heart and soul of amara.org, which is one of the organizations that we studied.

And then the other kinds of tasks that again are becoming more familiar to some of you, content moderation, classification tasks, that are meant to optimize your search query experience. So if you’re typing in something—and this will happen happen every election year. If you have a new candidate up for election, odds are pretty good if you’ve never seen that candidate before they had to do some work to make sure that when people were searching that term, searching that name, that it matched to the proper biography or person’s official presence online. So it’s kind of this renewal of a need for making sure the information is relevant.

I love the example of— How many of you remember a moment during the past elections when Romney made a reference to binders full of women? Right. To be able to figure out should that be a trending topic? Because if you just think about that phrase, that’s a nonsensical phrase. Aside from who said it. And so realize that took a lot of content moderators working very quickly to be able to identify oh, the context for that. Oh, it’s an election cycle, a candidate debate. Yes, trending. Makes sense. That’s happening below the surface. You will never see it happen, and it’s not something that can be automated, anytime soon would be my argument.

And then lastly thinking about these mundane uses of location verification. How many of you had a favorite restaurant that went out of business last month? Odds are if it moved somewhere the location needed be reverified and updated within search queries. That’s still very much the handwork of people below the API.

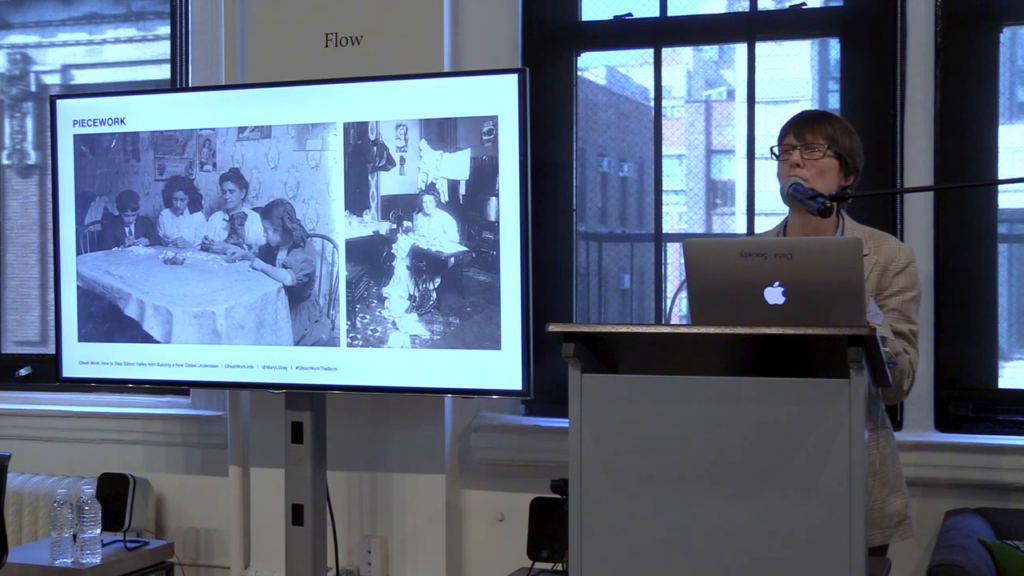

So, there’s a lineage here. This is not so new. And we take great pains to point out that the tendency to treat contingent work that seems like it’s going to go away anytime as therefore not that valuable and something we don’t need to care about in terms of our employment relationships. That’s old news.

So if you think about the experience of the Industrial Age and piecework and the work that was literally something that couldn’t be accomplished by the newly quickly-moving loom but that could be taken to mostly family farms in the United States context, and be able to share that raw material and the material that’s been created, say a shirt. And to have the button or the flourish of bows that could then be attached by a person. That’s the kind of work that the entire time the hope was eventually that would be automated away. And yes, eventually the machines were able to attach the flourish, the button, the bows. That didn’t mean that the work entirely displaced other kinds of work that needed to be put on the table.

This could go on for generations, and did. In manufacturing arguably. The only reason automation can knock it out of the park is precisely because you can build the factory around the automated mechanical processes and get people entirely out of the building. But in any case where you’re working with people, and effectively when you’re trying to serve their interests and anticipate their needs, you’re in an entirely different world of required task on a person’s time and cognitive ability.

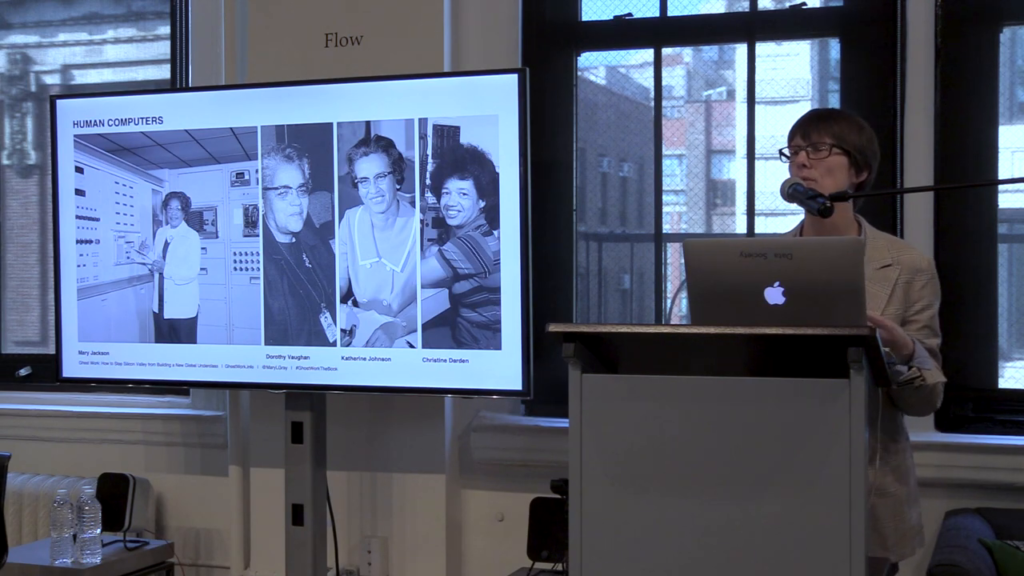

So, if you think about the next generation of lineage here, and the computers behind being able to put people in space or to be able to do some amazing technical achievements, we’ve always had these moments where the assumption was there’s something rote and uncreative about this work. It can be done by, and often is done by, the same suspects generation to generation. But their work is not seen as integral to what is really valued and worth retaining or underwriting through full-time employment.

So for much of the women who were involved in the Cold War projects through NASA and through other aeronautics institutions, they were on contract. They didn’t have full-time jobs. They could be released at any point, and particularly before it was illegal to fire women because they were pregnant, women could be dismissed as soon as they married because odds were good they would get pregnant.

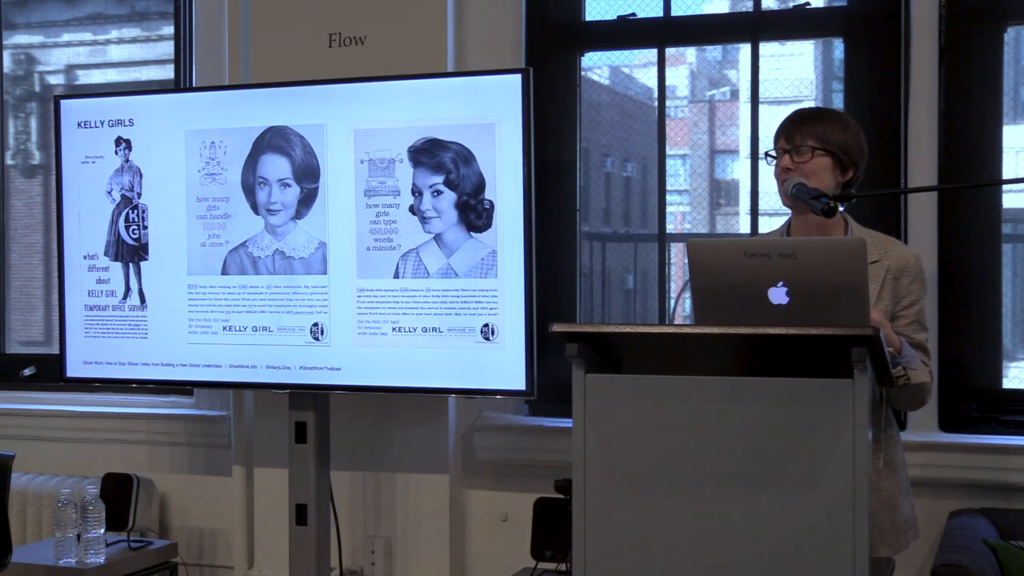

So thinking about this lineage it’s important to imagine who is often invited to take on these contract positions precisely because into the 60s they were imagined to be the perfect temporary workforce. Both able to do the work, as in Kelly Girls, and selling Kelly Girls as the opportunity for business professionals to have someone take care of their needs and then quickly exit to bring in fresh minds, fresh bodies, for the work that needs to be done around the office. So, you might see a pattern developing here in this lineage of who is seen as replaceable or less valuable and therefore ripe for contract work.

As we move into the early 80s to late 90s, and the Internet and connected communication devices allow the workflow of office work that otherwise seemed the domain of professionals, from accounting to human resources, to any sort of financial services, it becomes quite easy to take that work and move it to other continents where you have enough linguistic capacity to be able to take advantage of labor arbitrage, a cheaper workforce, and still be able to get the work done.

So, what I’m hoping you see in this lineage is precisely the set of assumptions that say who’s not so valuable here? Who is the person that should hold this temporary job? Because we don’t necessarily need to care about them too much. And what are all of the ways in which contingent work, particularly in the United States, set in motion a framing of contract work as disposable, less important? Contingency becomes a value proposition to the business, not to the worker.

So, the way in which we went about studying this, and I can go into this in the the Q&A, it’s really hard to figure out how to find people behind a distributed system who are working globally in their homes. I’ll be the first to confess that. I’m someone who really likes to find the people that people assume are otherwise really hard to find. Because it turns out if you just ask people, “Hey, where are those people?” they’ll quickly identify themselves and say, “Oh I do this work.” This was a whole other level of challenge.

And so, the way we went about it was to find four institutions, organizations, that were producing this kind of labor and then to figure out ways in which we could meet the workers who were participating in these labor markets. We work agnostically with the assumption that this is contract work unless it’s otherwise called something else. And we worked with the terms of the people who were engaging in these projects.

So we studied Amazon Mechanical Turk, which set the baseline for how most of task-based work is framed and treated, and the sidestepping of any legal frameworks or classification that go with it.

And then we also looked at the Universal Human Relevance System, which is the internal platform that Microsoft has. Please note, every large tech company has an internal platform, that you can’t see, that’s larger than Amazon Mechanical Turk, that has far more work than you could ever track. Because when it comes to the accounting of this workforce, it’s effectively the equivalent of paper. It’s not considered labor capital. It’s just an asset being bought and sold through a procurement farm, or through a procurement office.

So I say that coldly because importantly, that’s part of the legal framework and arrangements that exist between businesses hiring outside of their companies to be able to have full-time labor on tap through other firms that are the employer of record. So it’s a really important lineage to understand how it pipes into the back of several of these companies.

The other two companies we looked at, or organizations that we looked at, LeadGenius is a social entrepreneurship… It was a startup founded in Silicon Valley that generate sales leads. And they have a global workforce, with a lot of recognition that trying to do the work that they want to have done in the United States is not something they could legally do without being classified as formal employers. So they’ve moved a lot—almost all—of their workforce outside of the United States.

And then a fourth organization that we studied, Amara, Amara On Demand. I’m fascinated by Amara On Demand. And one of the cofounders and organizers of it, Dean Jansen’s going to join us for a conversation later. But what fascinates me about Amara is that it started out as a volunteer community, again doing captioning and translation of video, which is technically a very hard problem to solve. To be able to look at video in any robust way and interpret what are the actions that are happening in that video, that’s way beyond computation right now.

And this community of volunteers effectively became a magnet for companies and organizations that wanted to be able to translate and caption their videos in other languages. So companies started approaching them saying, “Can we just pay you to do this fast?” So it created a labor market that from it’s very beginning was organized by the volunteer energy and the attention to the workers doing the work for this community. And I think it’s a wonderful example of what we could be doing differently in terms of organizing these worlds of work around workers themselves.

So, in looking at these four companies it became an opportunity to start from there and to put out surveys on each of those platforms to be able to reach workers themselves and ask them about themselves. And at the end of those surveys to be able to ask them, “Would you be willing to meet in person for an interview?” And the map that you’re looking at… For work that is in theory work that can go anywhere, that’s available to anyone, you should see some patterns. There’s something that maps onto the infrastructure of outsourcing, of places where there are not many job opportunities that are comparable to service work at retail stores or in other settings where the payment is about the same as what you might be able to get in these online markets. So note the pattern, because that should tell us there’s something structuring again, who does this work, where they do this work, what are the other opportunities that it forecloses or suggests are not available?

And on top of those, once we had enough people interested to do the interviews it just turned into old-fashioned anthropology in a lot of ways. Of go to where the people are, meet people, see who would be willing to allow us into their lives for a long enough period of time to be able to understand the ebb and flow of their engagement with this work. So it becomes really important for example to be able to be in India and see what happens when the monsoon season hits, and how people then whether (no pun intended) the work that they have to do, which is effectively being online and having to be hypervigilant to pick up tasks that are then delayed by whatever might be getting in the way of their Internet access, for example.

The layer… And you know, hats off to Sid for figuring out the ways that he would be able to measure this world. Because I have to confess, I didn’t really care that much about measuring. I cared about if there’s anybody experiencing this world that’s enough for me. And thankfully, he helped me see there’s a lot of value in being able to understand the distribution of this work, the other patterns. And so what I want to share with you is really the outcome of merging these two approaches.

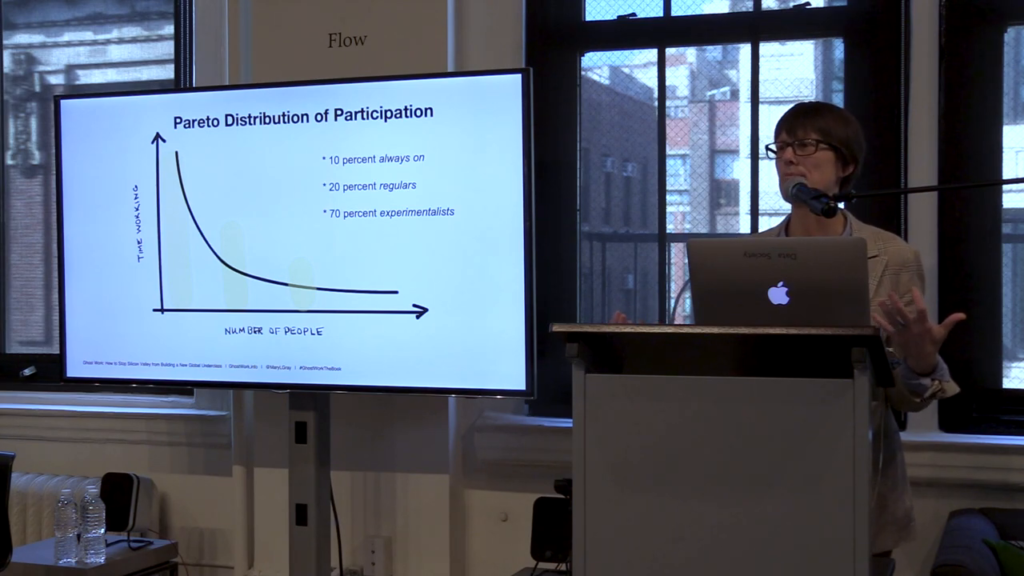

What we found was, and this is to me one of the most striking findings in the book, is that there’s a real Pareto distribution of participation. And when I say that, like so many other power laws that are out there it turns out there’s a concentrated few that are picking up and doing most of the work in these markets. So a good…depending on the platform, a good 10 to 15, 20% at most are picking up most of the tasks to be had.

And then there’s this core group of people that we call “regulars.” That first group, we call them “always on.” And they literally are. They’ve turned this into an income stream that maintains their livelihoods. And they might have other income streams and often they’re working on multiple platforms. They’ve turned it into full-time work for themselves.

The second group. There’s about 30% at most but closer to 20, are what we call regulars. They’re stepping into this, they’ve sunk the costs of figuring out how to make these platforms pay off. They’ve learned what they need to learn. And importantly they’ve connected with peers. Much like the always-on have, they’ve connected with discussion forums, other people who help them manage and figure out how to reduce their costs getting this work done. They are the bench, the deep bench, that is always able to step up into this labor market and pick up a task and do it. And it is what allows anybody who’s always on to step away and not have the entire market just fall apart. The argument we have here is there’s no way to turn this into fully on time, always on work. To turn it into full-time work precisely works against what it is that people who have entered this world have said is important to them about entering this labor market. I’m going to come to this in a moment.

But lastly and most importantly, there’s a good 70% of people who walk into this—we call them “experimentalists”—try it, and they’re like, “Peace out. Don’t wanna do this.” They have a range of reasons they decide they don’t want to do it. All of them are still providing value, both to the companies that are able to claim that they have 500 thousand workers on demand. So think about any time you’ve used Lyft or Uber, being able to see enough of those little cars that tells you okay, I’ll bother. That’s the value all the experimentalists are bringing to this market.

And picking up one task or two tasks, it is precisely being available that they are offering. Being willing and available. That’s the most valuable thing that they’re doing. And I think it raises this question of, “And yes, isn’t that valuable?” Why isn’t that considered valuable? They’re bringing an incredible amount of value certainly to the businesses. They weather all of the costs. These are in most cases the people who could not figure out how to tap into a communication network to make this manageable, often felt isolated, and alienated.

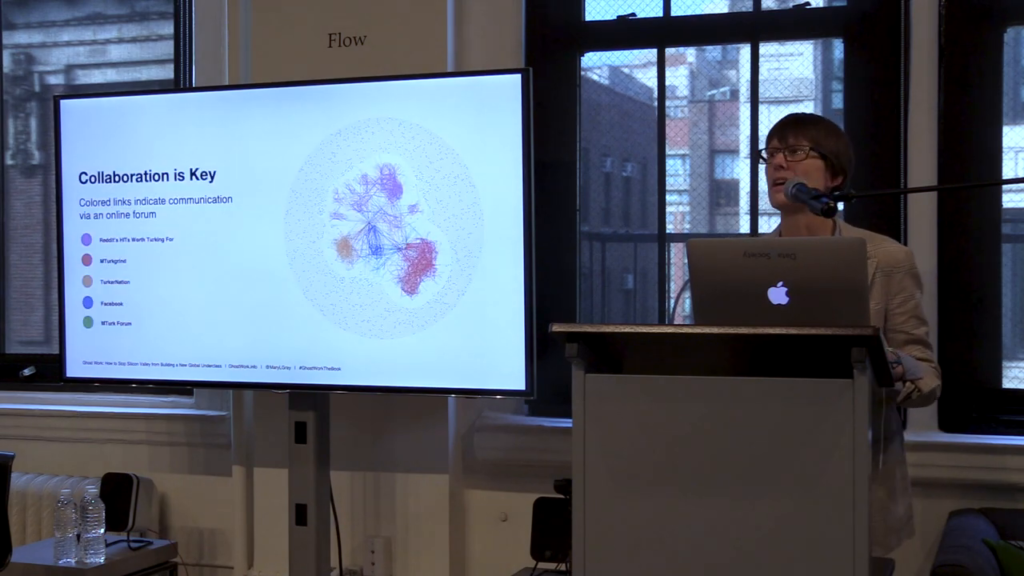

So, collaboration is key in this environment. The thing that allowed people to find their footing; to be able to make enough money to make this worthwhile; and again, the trade-off being being able to do it on particular terms, was tapping into a network. This is from an experiment that Sid Suri and one of our coauthors Ming Yin developed to be able to identify what were the communities that people were engaged in—discussion forums. The different colors are the different discussion forums for—this is just for Amazon Mechanical Turk. So an incredibly robust, rich, nuanced, complicated environment of interaction. And all of the small dots are the solitary workers.

So the vast majority of people who haven’t connected with somebody are there, still providing value, but you’ve got this tight cluster and groups who are organizing around specific communities who again really scaffold with each other and make this manageable work.

If you have to work through the night, you plug in earphones, put the phone to charge, and talk all night.

Akbar, an on-demand worker in Hyderabad, who talks with other workers while he works nights. [slide]

I wanted to share this quote from one of the workers talking about how important it becomes to be able to connect with other people doing this work. I think the deep irony here is that the platform builders assumed this is great work because you can do it alone, and you don’t have to interact with anybody, you don’t need any help. what they hadn’t anticipated, perhaps because they didn’t have enough anthropologists and sociologists in the room, was that people might still be invested in having social connections. The social connections are actually incredibly valuable to getting work done. It’s just immeasurably valuable. And that’s part of this environment, is figuring out how to recognize the value of that connection.

The motivators that came up most often, and this might sound trite, it actually maps on entirely to the literature we have already about how people talk about their work, what they value from work, particularly when they decide to be self-employed or to try and freelance. It’s about controlling your time, and I’d like everybody to stop using the word “flexibility” if you please. Because this isn’t about flexibility. It’s about having other constraints on your time and needing to control your schedule, often having to do with family care, elder care. child care, other work responsibilities and other interests. Having interest in other education. Other hobbies, other joys. And in most cases people doing that calculus of “how can I make this kind of work sustain me so that I can make my life run the way I want it to run?” That’s aspirational to be sure but it’s certainly part of what motivates people to keep at this.

The second thing they’re after is to be able to control what they work on. And I’d imagine many people in this room share that. They’d do just about anything to be able to define what their project is rather than have somebody else tell them what to do.

And the third is controlling your work environment. And if you’re pushed to the margins, controlling your work environment is not a “nice-to-have.” So people with disabilities, queer-identifying people, women who felt marginalized by the formal employment opportunities in their area all talked about this work being away of relief from those other constraints.

I can make money wherever I am and work on things that matter to me. All I need to do is take my computer with me. I’m living my ideal life.

Carmela, an on-demand worker in the US who does ghost work to support her dream of being a choreographer [slide]

So when Carmela is talking about effectively being able to turn to this work because she can then pick up her computer and do it from anywhere, I want to take very seriously and not dismiss her claiming that this is the kind of work that lets her live her ideal life. It’s how do we recognize, take that at face value, and still remain critical of a system that might still take advantage of her desire to do this work, without somehow thinking that Carmela is the problem here?

So, I want to move into thinking about where do we go from here? What have we learned from the way these workers not only survive this work but make it meaningful, that we could then use to redefine this world of work? Because I’ll continue to say, this is early days. We have an opportunity to really design this purposefully, with people at the center of our equation.

So I want to focus on two things. If you get the book, the entire conclusion is just here’s what we could do. It’s my bucket list, that comes from the bucket list of the workers we engaged.

But the one I want to focus on for this conversation is to think about what it means to redefine the social safety net and job classification. I’m just going to say it, I would like to completely blow up employment classification as we know it. I do not think that defining full-time work as the place where you get benefits, and part-time work as the place where you have to fight to get a full-time job, is an appropriate way of addressing this labor market. And particularly if we consider that globally there are so few people in the world who have ever had access to full-time employment that provided any benefits.

So let’s start organizing our classification and treatment of employment with all of the contingent work we’ve seen in this lineage and imagining that we will be those workers in the future. And if that is the case, then the best thing we could do is say there are some basics here. That we’re building a commons. We have a labor commons that every company benefits from being able to draw from. They can dip in and out of this pool. So, how are we going to support that pool? How are we going to make it sustainable? So that the value proposition isn’t here, let’s just exhaust this pool and drain it. Because that’s a tragedy. We know of the tragedy of the commons. Apply the same logic. Imagine if Healthcare4all isn’t just a nice thing to do because it’s charitable, it’s like that makes business sense. You need a healthy workforce. You need people to be able to step in and out of it to be able to make it sustainable.

Continuing ed, there wasn’t a person that we interviewed who didn’t talk about how often they were going to online resources to be able to continue exploring what were the kinds of materials they needed to follow up on and choose to read to be able to do their next project. We all benefit from being able to do that. Everybody had a baseline of a liberal arts education. The big news is, a liberal arts education and learning how to learn is the baseline for every worker in this market. Because it’s creative work. All of us had to learn how to learn as that baseline and then build from there. This is not specialized work. This is using your brain all the time. So the basic education that comes with critical thinking is key. And then being able to make everything else available becomes critical.

And then thinking about coworking spaces, I just want to leave you with this vision. When I saw all of the home office setups of everybody we interviewed, and at the end of the day thought of the health and safety administration and what our workplace around health and safety was set up to do, it was to prevent public health crises. We have a public health crisis in people setting up their home offices and not having resources to do it in a way that’s healthy. So I know that sounds small, but every municipality could have coworking space that is thinking public health. That’s an intervention at the public health level. Everybody should be able to get to a space where they can get relief for their back, for their neck. Again, sounds trite, but if you’re doing office knowledge work, it’s critical.

And then lastly I want to dwell on this notion of a retainer. So, there’s a lot of conversation about universal basic income as a solution here. What frustrates me most is the framing of that suggestion is that these are the poor souls who can’t outrun the robots. That doesn’t really account for how much what we really need is to retain the cognitive and creative capacity of people to be available to businesses, to each other, for service work. So people should be on a retainer, for sure. Give everybody who’s a working-age adult a retainer that says here’s your baseline so that you don’t have to think about paid leave or unemployment. But that literally you have what sustains you to be able to step away when you need to step away. Have children, take care of someone. And at the same time know that you are going to have the financial means to get back into that commons, right.

Very different attitude than universal basic income. The idea that somehow the poor are going to rise against us, and therefore we need to give them some small amount of money completely misses where is this economy headed? It’s a service economy. It’s an information service and care economy, where we’re caring for each other. And so to be able to do that, we really have to imagine how would we give everybody the basic support financially to do that, to be able to come and go in that work?

So, the last thing we have to do is on us. If you use any of these services, now is the time, and today is a great day to do it. There’s a strike by Lyft and Uber drivers. If you’re a consumer of any ride-hailing app, be thinking about, critically, if you’re somebody who consumes with care, if you think about where you buy your clothes or buy your food, there’s nothing small about that movement. Consumer advocacy and boycotting have been incredibly powerful. They led to the Bangladesh Accord, which was the beginning of holding companies accountable for the long supply chain involved in getting the shirts on our backs and in thinking about agriculture and places where knowing the supply chain became critical to making sure the quality of food, but the quality of people’s work conditions growing that food was something everybody could know, and then make your choices. And that will never be enough. This is not a land of let businesses be kind to workers, or let consumers be self-interested consumers. It’s about setting up the possibility for the right regulation and classification for employment of the future.

So, the key takeaway, other than AI always requires people so we’re not getting rid of them anytime soon, is that this is a commons. This is a labor commons that relies on people coming in and out. And what will it take for us to be able to support and value labor? No matter where it happens, no matter how many hours somebody puts in. Because in fact, the value of these markets, it’s aggregating up what we do. It is literally the aggregation of everybody’s input. And from there, what it’s providing. So think Uber. It’s all of those drivers being available to you. It’s not just the one driver who took you to the airport. So to be able to value all of the aggregation of that labor and say what will it take to say each of the people participating in that are equally important to our livelihoods, to our lives?

And with that, I want to thank my collaborators. Because there’s nothing like a book about this kind of work to make you hopefully always aware of how much— Everything that went into this book came from an incredibly rich team of people bringing a range of expertise. From Greg Minton, who made the beautiful maps. To all the research assistants who were involved in doing the fact-checking. To the key research assistants that we had in India to be able to maintain the contacts with the people we had met through fieldwork. So there wasn’t a person on this team who didn’t do something integral, that if they weren’t here I don’t know that this book would be here either. So with that, thank you.

Sareeta Amrute: Thank you Mary. That was amazing. I’d like to invite Dean Jansen to join us here at the front of the room. Dean is the Executive Director and Chief Executive Officer of the Participatory Culture Foundation, the parent organization of Amara on Demand, co-leading PCF with Aleli Alcala. Amara is featured in Ghost Work and we’re thrilled to welcome him into the conversation.

So as moderator I’m going take the host privileges of asking a few questions of Dean and then Mary. And then I’ll open it up to the floor for discussion.

Dean, maybe I’ll start with you if you don’t mind? Okay. If you could tell us a little bit about what’s changed for Amara since the book was written.

Dean Jansen: Sure, yeah. This was a great question and one that you know, thinking about what has changed as an organization, we’ve gotten bigger. When we started, and when AoD was first starting, I think the staff was about nine to…twelve people? The initial group of folks that were doing the translation, around two hundred. And today the staff is closer to thirty. There are thousands of different folks who have signed on and are working with AoD at this point.

And then as far as just the marketplace, that’s something that you know…when we began there was obviously a robust translation marketplace. But the audiovisual subtitling and dubbing side of things was still pretty nascent. And that’s really starting to pick up more and more today. So those’re two areas that have changed significantly.

Amrute: One thing that Mary talks about in the book is this idea of the double bottom line. And she talks about that specifically when it comes to Amara’s work, which tries to create fair and collaborative labor practices for people who are doing translation and subtitle work. And so what I wanted to ask you Dean is, how do you respond to people who say that the double bottom line is a nice idea but it’s not really practicable. That in fact a business like yours can’t sustain itself with that model in place.

Jansen: Yeah, that’s a great question. And one that I think might be answered well with another question, which is what does it mean to be sustainable from organization to organization? Again, in the space that we’re in, in translation, we saw early on these kind of more-established players had very high margins. And so again just a just a question of, how do you define sustainability? Sustainability for whom and for what?

I think if you’re asking more maybe about kind of the lower-margin end of things? We’re talking about some companies that are the biggest and most powerful and profitable in the history of the planet. And so I think it’s a question less, in our eyes at least, of is it sustainable? More a question of how can we make it sustainable?

Amrute: I’ll just name MTurk as one of those companies, since Dean was too polite to say it.

Another question I wanted to ask about is really playing off of what Mary was talking about at the end of her talk. We can think about consumer advocacy. We can think also about regulation. In your mind from where you sit, what are the possibilities and limits on what a business enterprise can do to value and protect micro labor?

Jansen: Hm. Another great question. I think… Well, let’s see. So, as far as the limitations go, I think there are a lot of things that organizations can and should be doing. And we were kind of joking about the—not joking, but a couple of weeks ago talking about how low the bar is when the bar is “recognize that these are human beings that are doing this work.” Early on when speaking with Mary, one of the things that really struck me was her describing conversations she would have, as she mentioned, with engineers who really didn’t see where all these layers existed with human labor in them.

So to me in many ways, the work that Mary and Sid and all the people that have made this book possible, all the people that Mary spoke with, shining a light on it and making it visible as like the first step in figuring out… I think I’ve just…skipped your question, but in terms of like, zooming out and looking at societally what can we do and how can we accomplish some of these things? Just that first step of having some recognition of who and where people are is really important. But obviously on an individual organizational level, there is a ton that can be done.

Amrute: Can you give us just a few examples from your own experience?

Jansen: Sure, yeah. So let’s see. In terms of… I mean, again, providing people space to communicate and work with one another, one of the things that we found in translation was there’s this kind of stereotype of the lonely translator. Someone who is working in an isolated sort of— And in many ways, that’s…again, I’m not a translator so this is just my learning and understanding of it. But historically people do…it has been a more isolated kind of work. So for us, bringing the collaborative side of the tools and platform that we’re providing and building, to continue listening to what sorts of things people need to do their work better, and to collaborate more effectively. That’s been something that’s been…that’s kind of the bread and butter of some of what we’ve been doing.

Amrute: Thank you. Being cognizant of time, I will just ask Mary a few short questions and then open it up to the floor.

So Mary, one of the key concepts in your book is this paradox of automation’s last mile. Could you pull that out for us a little bit and maybe relate it to the lineage of contract/contingent labor that you put up for us, which in your book actually very interestingly starts with the experience of slavery in the United States.

Mary L. Gray: Yeah. I mean, to think about this paradox in many ways is to grapple with what has been the use of the lion’s share of manual labor, for example. And early days with you know, if we think about what defines modernity, what defines our modern era, it’s imagining we’re going to get our hands out of the soil and be able to put our minds to work. It’s an erudite notion of what does advancement look like? What is progress, and progress driven by technology?

And so the paradox is that as we strive to pull ourselves out of manual labor, I believe we start recognizing that it actually takes quite a bit of creativity and complexity to be able to do any enterprise, to be able to do anything productive. So starting the lineage with slavery in the book is to say that was really our first labor law in the United States. It defined who could be owned, who could be used in a way that only treated their bodies as valuable, and didn’t imagine that any kind of work that we do involves a human capacity…not to be too humanist here…but a human capacity to be able to bring creativity, to be able to bring responding to spontaneity, to whatever we’re doing.

So that moment of delaying recognizing the value, the real deep integration of creativity with everything that we do, I believe that is this moment. It’s this reckoning with a paradox we keep introducing of thinking we’re just gonna…we’re going to get the thinking and the talking out of it. It’s just going to be something we can automate. And then we’re just left with things that are really hard, you know. The professional class will be able to do the really hard work. It throws to the wind the idea that taking care of…if you’ve ever taken care of an elderly parent? That takes a lot of thinking. A lot of creativity.

There’s a beautiful book that really for me sets up the discussion of the paradox and it’s by Levy and Murnane. They’re a computer scientists and an economist who talked about the new division of labor. And they were trying to analyze what is it that a computational process can do, and what is it that a human can do, that are really distinct? What is that division?

And so we’re trying to theorize why it is as we strive to automate things we keep discovering anew that the capacity to think creatively is in the thick of it? And that as we keep pushing to automate and reaching for having something else do things for us, we’ll keep discovering those bits that are really the heart and soul of what what humans do, which is sense each other’s needs, anticipate, and I joke often: be able to apologize when we get it wrong. Like, computation can’t do that.

Amrute: I’m going to just ask one last question. I know there’s a lot of people waiting.

One thing I wanted to underline which I loved in your presentation, and in the book, is the way that you use the task of Mechanical Turk itself to set tasks to get research for the book. I think this is a brilliant methodology. So I just want to put a big fat line under that. And then based on that I wanted to ask you if you could pull out for us the significance for you in doing transnational, comparative work, especially as it relates to identifying the challenges and opportunities in labor organizing?

Gray: Yeah. No, I mean I think from the… To be clear, starting with India and the United States in some ways was following the labor markets that Amazon Mechanical Turk had created by paying in both cash and rupees. They had built this labor market by design, without probably much thought, certainly, about the kinds of workforces it would create. And in drawing that comparison, it meant we were constantly able to pull out the places where connection broke down. The kinds of nationalisms that would spark around different workgroups, for example. So the transnational comparison gives us a chance to see where do people throw boundaries back up.

And I thought it was most striking in India how quickly a kind of pan-Indian way of orienting to work, across all the platforms, also came to the forefront. So the number of women and men who would start referring to each other as sister and brother to navigate the gender politics of working in settings with somebody of a different gender. The amazing use of English as a way of navigating linguistic boundaries, and what that can mean. The meshing and sidestepping of religious and caste differences. Those complexities could come out, and in some ways being able to see the complexities around class and race that played out in the United States in different ways, really came to the fore with that comparison.

The technique of putting the surveys online…I think in many ways I’m really dedicated to us always imagining that anthropology, sociology…of engaging people’s lives means getting in their lives? I have a difficult time feeling like stopping at a discussion forum and letting that stand in for people’s experiences can answer the questions I’m interested in. I think it has everything to do with the question you’re asking. But for the most part the question we were asking was “What does the rest of your life look like?” And so there was really no way to ask that without moving from those platforms into their living rooms, into the cafes they circulated in. And that became the the methodology.

Amrute: Thank you. Who would like to ask a question? danah?

danah boyd: This is Mary’s fault, she set me up. She was like, “You have to ask a question.” and I was like—

Gray: A hard question, please.

boyd: Yeah. Alright, ready? So, much of what you’re grappling with is a dynamic that we’ve seen iterate over and over again throughout history. And you’ve pointed to them by talking about the enslaved people and as a form of contract within labor markets, where different versions of capitalism have evolved in response to these different governing structures. And we keep seeing a regulatory move, and capitalism evolves. We are now at a late-stage capitalism structure, where we’re not only seeing the efficiencies that are produced by capitalism as an operating system but reinforced, as you point out, by technical systems.

But we’re doing it in an environment, to sort of riff off of Sareeta’s point, where we’re not actually dealing with bounded nation-state structures. And I’ve noticed you’re not screaming to tear down late-stage capitalism…mmm, maybe yeah—you know I know you. But part of it is how do we actually think about the boundary work of nation-state structures and the evolutions of late-stage capitalism as something that can actually grapple with this so that it doesn’t just keep slipping and evolving?

Gray: So two things popped in my head the last week or so. One is thinking multinationals have figured this out in some ways. They know how to cash flow. And so to take at face value that multinationals generating quite a bit of wealth internationally and circulating it internationally can’t figure out how to circulate and distribute the value seems—

boyd: [inaudible] saying they should govern?

Gray: Uh, hell no. No, they should not govern. No. It is to say there’s clearly a way to exchange money, globally. I’ll just…I’ll say it flatly like that. And that means in terms of governing the revenue generated, the redistribution of it, that is a global conversation. We know that multinationals are regulated in in specific countries; start there. So, make the United States, make the EU, the battleground for saying, “New classification. Everybody gets basics. Go from there.”

I think it’s for me very frustrating to realize how many large companies—and we’re pretty much in a monopolistic world here. How many of the large companies that have merged and acquired each other have been able to stay on the sidelines of a conversation around universal healthcare in the United States. That makes no sense. And it should be on everybody’s mind to be advocating to these companies, and it can’t be about just advocacy but certainly making the case “Why are you on the sidelines? You benefit from being able to see this healthy workforce.”

And in fact one way to think about this is supply chains and good work codes for enterprises to say there should be a call for regulation that if you are hiring a vendor, you should make sure that vendor provides healthcare, just as you are required or at least benefiting from providing healthcare. I think there’s a business case there. Can it happen without regulation? No. We all need to say this is ridiculous that we don’t provide basic healthcare. And I would just keep making that case.

But the second thing that came to mind is that it really is on all of us to stop letting liberal and neoliberal economics define the value of labor. To call labor a marketplace and not see the moralism within that… Like, I’m just going to spell this out just plainly. We have allowed people in elite positions, both government and private enterprise, to say that our labor is the same kind of capital as a set of records or a car. We’re not durable goods. Labor means something else. So let’s stop assuming that the marketplace sets the value of our labor. My salary is not coming from some magically-discerned value of me on a marketplace. It’s coming from power. I have a particular kind of power and privilege to command a price. And that is a set of irrational power moves. It’s not the logic of the market playing out.

So I really want us all to start questioning. There should be no turn to the market “what is the market paying for this task?” It should be, baseline, labor deserves support, because we need healthy workers to move the world forward. I’m a pragmatist, that’s why I’m not that interested in blowing up capitalism writ large. I don’t know, you could probably get me there, danah.

But there are alternative versions of marketplaces like cooperative marketplaces. Marketplaces we haven’t even imagined yet because we haven’t let ourselves think that the market can’t set the value of us. Nor should it. And that’s why that lineage started with slavery. Why would we have ever imagined that the market, or a market, should define the value of humans? Let’s stop that, and set a baseline. And then go from there. Perks, sure you get perks if you’re an extra good worker.

Audience 2: I think I might have a simple question, but I’m sort of thinking as you’ve been talking about people’s power and how we might choose a baseline that might be a retainer or some sort of work for all. Do you think that that might be really difficult as more and more people are doing labor unwittingly? Like for example Google uses verification to make sure you’re not a robot. And we’re like, “Great. That’s great. I want to prove I’m human,” but you’re actually doing work for…you’re doing that task and you don’t know that you’re doing it. So do you think that like Hulu or subscription services are going to start making people do work in order to watch a video, and because they want to watch it they’re going to do work like in these microtransactions? Do you see that maybe killing the labor force, too, because all the work’s going to be spread out to everyone that are very willing to watch their content to do it?

Gray: So, love that question. Two really optimistic reasons that I think that won’t happen. One is that when people become more aware that when you check the “I’m not a robot” that you’re actually doing work for a company that makes a lot of money and doesn’t actually make your service better, we should all be saying, Hell. No.” And it’s not that we’re going to walk away from it, because we’re all enjoying those services. It’s that we’re all going to become publicly aware that you are having your time taken. You are having your time taken without your permission. That should never be okay, right. So, one answer to your question is we absolutely have to have more public awareness of the sheer robbery of our time that’s happening.

We make pains—the second response to your question—we make pains in the book to distinguish between paid labor and unpaid labor. And the reason to focus on paid labor is precisely to say that it’s a different relationship. It’s a social— it’s not a charity when you get a job from somebody. You’re providing value. It’s a business transaction. Be cold about it. So that we can start living our lives and stop having work define who we are, right? Like this is— Kathy Weeks is one of my favorites on this. It’s like, why are we not fighting for the end of work rather than for a forty-hour work week? Hell, no, right? So let’s go there. And I think the beginning of it is with an awareness of when we are giving away…and actually I think that’s the wrong framing. When our time is being taken from us. Let’s stop saying we’re giving it away. Because our time is being taken from us. Without our permission. And we have to say that’s not okay. That’s the first part.

Amrute: Okay, last question.

Audience 3: Thank you guys. This is just great. So I wanted to ask about… I’m looking at the cover of the book and intensely wondering who is this person. But it brings back the question, the topic of the visibility of people doing this work and their relative invisibility. And I wondered if you could talk about that and talk about why or how that visibility might be important to the bigger equation of change that you imagine.

Gray: There’s not a day that goes by that somebody doesn’t tell me about their Lyft or their Uber driver when I talk about this book. And so there’s clearly something poignant and pressing for people when the person that they’re worried about is right in front of them. I mean and that’s a good thing. And I think in some ways let’s tactically deploy that if you’re an organizer.

I do think we care. I mean you know, I’m a relentless optimist. I think when we see someone in pain we want to relieve it? Usually we save that for people we love the most, but our impulse is there. And so I want to believe that by raising visibility, by seeing the people who do this work, that it changes what we want for them. You could just be crass and cynical and say, “This could be you. So don’t you want to change your circumstances?” It will absolutely be someone in your life. Do you want to see their life better?”

So I think it is for me— It’s funny you raised that. The cover was actually really… I was uncomfortable with that cover. I found it sensationalistic. I’ll just say this, I love my press, I don’t know if they’re here right now. Clearly what they wanted was to get this book in peoples’ hands and they wanted something that people might reach for. And it might have that effect. I hope it does. That was their reason. For me I’m now on this mission to find out who is he, you know. And I’ll get back to you. I’ll post something. I’ll find out who he is.

Audience 3: [I mean?] how else can you make people visible. Other than [indistinct] book.

Gray: Yeah. And that is actually a really complicated question. Because at the end of the day, for the people I interviewed, they’re folks doing their jobs, living their lives, and they’re not particularly interested— And actually for the folks I’ve asked, “Do you want to be on any of the TV shows I might be on?” And the first thing they say is, “No.” And the second thing they’ll say is, “I don’t have time.” And the third thing they’ll say is, “I don’t want to be seen as one of those people who’s a victim.” So what I don’t really appreciate is most of the coverage out there frames the people who do this work as victims, or dupes, or unaware of their circumstances. The people doing this work are painfully aware of their circumstances. And we would do best by listening to them. I think we could just listen rather than need to see them. This isn’t really about making you see everybody who’s had a hand in making your social media palatable. It’s about knowing there are people who are helping you. And they’re working. So how do we support them?

Amrute: Thank you very much. Buy the book. It’s over here. Thank you, Dean.