Good afternoon. My name is Chris Clark. I’m here to talk to you today about the intersection between design and linguistics, which seems very apt given the topic of this conference.

Linguistics is a social science. It’s not unlike anthropology or sociology, those studies that have helped us so much in the design field for the last few decades. But linguistics is the study of language specifically. Not of any particular language. I only speak English. I tried French and Italian; didn’t take. But human language in general, as a phenomenon. Our unique ability to produce and comprehend language, and the evolution of language over time.

In particular if we look at the intersection of interaction design and sociolinguistics (sociolinguistics is one of the many many subspecialties), we look at how language affects our social interactions. That is to say the consequences of our words on the people we speak to. And to turn that around, it goes both ways. The interactions we have have an impact on the words, and have an impact on the language. Our interactions as people define cliché, they define taboos, they define what’s offensive and what is humorous. Because humor and offense are not inherent to language. There’s nothing inherently offensive about any word, but the things we do with them cause offense or amusement. And those things change over time. The march of society is that we continue to evolve as a society and so our language does as well. Our usage of language as a people changes the meaning of individual words.

And as people who are working on predominantly software, and with software becoming increasingly social, the impact of language on our online interactions is increasingly relevant to us as designers. The names we use for features, the prompts that we put in the UI, can make people confident and comfortable with the platforms we build for them, or they can make them feel nervous and guarded. This is true of social software, where the prompts that we give them set expectations of behavior when they’re going to be interacting with other people. But it’s also true of single-user tools.

We’ve been doing this for a long time already, even before social software became a thing. We’ve already been exercising our ability to set people at ease or put people on guard, with color and animation and shape. We’re already trying to control emotional affect every day that we’re designing. Because we know that mood impacts usability.

Twenty, thirty years ago now, Don Norman was telling us about visceral design, behavioral design, and reflective properties in design, that these very simple things can in fact impact how we feel and how we act further down the line. And that’s why we design attractive software. That’s why we want to make bright colors and smooth shapes, to put people at ease. And language can play a huge part in this. Because design is already about communication. We’re communicating affordances, we’re communicating expectations to our customers, to our users. And we’re communicating our brand values.

But we try to do as much as we can with this non-linguistically. We try not to rely on words because we know that people aren’t reading them. We know that they’re just skimming and we can pray that they get through one or two words to get the gist of what we’re saying. But even though we know that words are the lowest priority for any of our users, they’re still an integral part of our work.

As designers, we’re inevitably labeling things and naming features. We’re writing error messages and tooltips. We’re trying to help people navigate through these complex interactive tools. And we know that marketers and content strategists and other people will eventually get in there. They might polish up a few words, they might give a feature they’ve been working on a stupider name so that it can go public, and they might change things. But more and more often, the words that we used in our wireframes ends up what’s shipping out to the public. Which should give us pause. It can be a little scary to think that something that you wrote just off the top of your head in two seconds ends up shipping to millions of customers.

Because language is functional, even when it was poor form. Even when we do a bad job, it still works. But as professionals we’re striving for good form. That’s why we’re here. We’re trying to do better than the baseline, because language is an aesthetic pursuit. And understanding it and mastering it isn’t just aesthetic, it’s not just a subjective act. It can be enhanced by science. We can objectively improve our communication. Which is why we can turn to fields like linguistics to help us out.

But the question is, is communication really that difficult? Because we do it every day. We’re pretty well-practiced at it. But you could say the same about dressing yourself or feeding yourself. I’ve been eating terribly the last few days because I’m traveling. But just because you do something every day doesn’t mean you’re doing it well. And just because we all have the capacity to write doesn’t make us all writers. Because effective communication isn’t up to us.

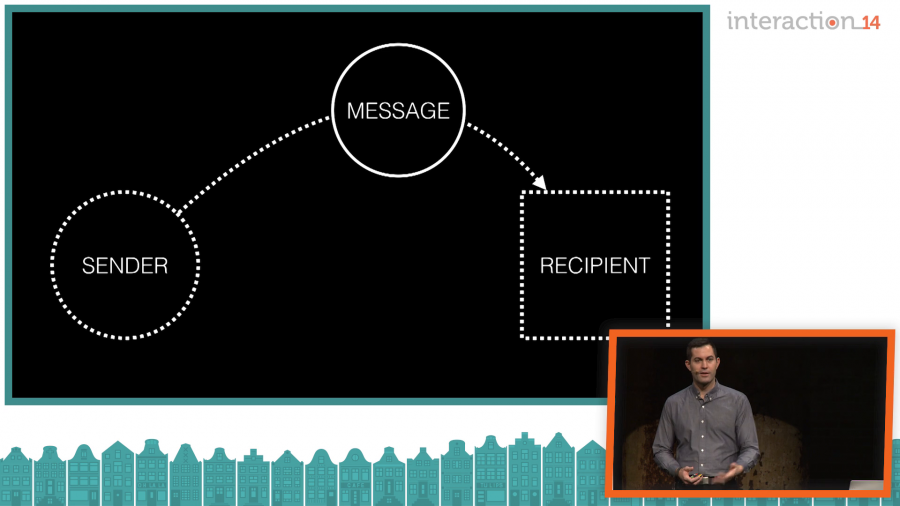

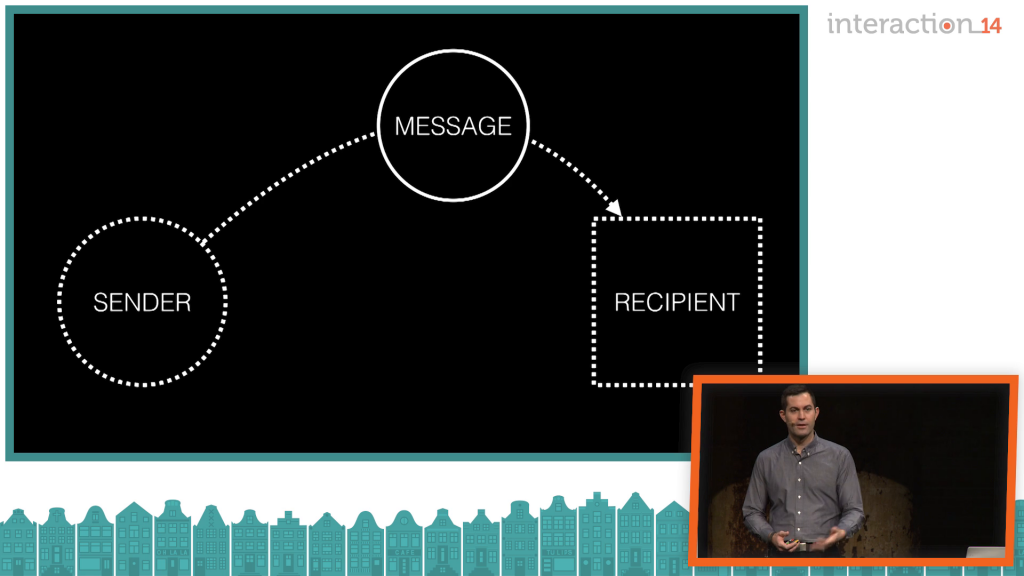

Any communication has a sender and a recipient and a message, and you can only do so much as the sender. If the message is sent in a format that the recipient doesn’t understand, it’s meaningless. All of its meaning is completely lost. You need to speak in a language that the recipient is expecting.

But what is language, really? From a linguistic perspective it’s just any sufficiently complex system of communication. Which is kind of tautological. But when we as lay people talk about languages, we think of languages that have names like French, and Dutch, and English. But what we call “English” is not a language. It’s a complete mess of languages. English is a mishmash of thousands of subsystems of communication. English is just a convenience label; it’s a political label that we use. Because there is no one definitive English language. Even in England, English people are terrible at English. There are too many kinds of English in England to comprehend.

And there are these cultural and geographic variations that cause miscommunications. Where you learned to speak, who taught you to speak, these impact greatly on how you speak. It creates a cultural identity for you that you take with you around the world. In linguistics we call these dialects.

I grew up in Western Australia, and I learned to speak Australian English there, which is heavily influenced by British English dialects, especially in the West Coast. Because you know, they send their convicts over on boats and the convicts bring us new dictionaries every year, so that’s where we get new languages. But I live in the United States now, in California, which is decidedly not British. They fought a whole war over it. So I’ve had to learn this United States English dialect.

I remember the first time that I introduced myself when I arrived. I walked up to somebody and said [affecting an Australian accent], “G’day, my name’s Chris Clark.”

And they said, “Clock? Like, clock like you’re telling the time?”

“Nonono. My name’s Chris Claaaarrrrk.”

That was my first step in this journey of learning the American dialect so that the people I was talking to could understand me better. And I had to change whole vocabulary words. In Australia we say toilet, in the United States they say bathroom. Spanner became a wrench. And tomato sauce (or [Australia accent again] tomahto sauce) became ketchup, which is especially relevant because in the United States tomato sauce is something you put on pasta.

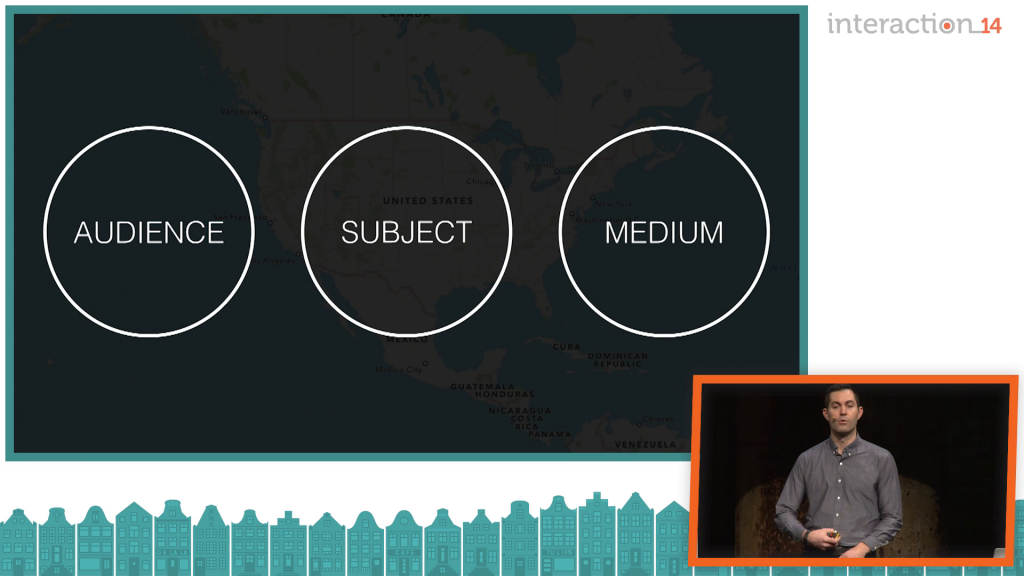

So while dialects are tied to who you are, tied to where you come from, there are other kinds of variants in language. There are situational variants. You can have contextual languages that you don’t use all the time, that don’t have to do with strictly who you are, where you came from. And rather than linguistic differences between two people being determined by who they are, you can have linguistic differences that are determined by who they’re talking to, or what they’re talking about, or the manner they’re talking to each other. We call those diatypes. Actually there are dozens of words for this because this is still kind of an in-progress research in linguistics. They can be called mesolects, they can be called registers. Diatype is just sufficiently unique and similar to dialect that I decided to use it here. Diatypes can be, for designers, kind of our secret weapon for communication. So I’d like to go through some of these things.

For audience, when you speak to different people, you speak differently. You literally speak differently. You use a different vocabulary. You use a different intonation. And you speak at different speeds. For instance, if you wanted to ask someone what they liked about their dinner last night, and say it’s a peer of yours, say it’s your boss, you might just say, “How’d you like your dinner?” But if you’re talking to a very small child, you probably lean down and say [affecting baby talk], “Did you like your numnums?” And if you’re talking to a very old person, you might yell a little and just say, “How was dinner?” It’s the same message delivered three different ways, and it’s dependent on the recipient. It has nothing to do with you. In a way.

And you’ll speak differently whether you’re talking to a friend or whether you’re talking to a salesperson or whether you’re talking to a police officer, and that’s where the name of this talk comes from. You could imagine if you’re in a bar with some friends and you’ve been talking to your friends for hours, and then you receive a phone call and it’s your mother. You spend a few minutes on the phone with your mother trying to get her off the line because you’re in a bar. And when you hang up your friends turn to you and they say, “You have the weirdest mom voice.”

And it’s not that you have a weird mom voice, it’s that you have a weird everything voice. The voice that you use for your friends is drastically different to the voice you use with your mother. It’s drastically different to the voice you use with your boss. All of them are weird voices. And these variants are actually indicative of power relationships with the people in your life. The people who have more power, more authority, and more respect are spoken to differently in our society.

These reflect our cultural biases and our prejudices. In the child-directed speech example I gave earlier… Child-directed speech is a well-studied diatype, because it sounds so weird. We exaggerate our tones. We simplify our words. We speak slower. It serves an educational function. We’re trying to show the kid the patterns of the language so that they can pick it up and learn it. But in the elder-speak example, it doesn’t have that function. There’s no educational function. We’re making assumptions about the elder person’s cognitive ability and adjusting the way we speak accordingly. Which is a little insulting. I hope that as I get older people don’t start talking to me like I’m an idiot. But this is a prejudice that we have. And when you hear yourself doing it to different people as you go about your life talking to different people, talking to your boss, talking to people at restaurants, you can notice yourself doing it. And it’s fully subconscious; it’s a completely automatic process. But knowing this about yourself is very revealing. But forewarned is forearmed. You can learn more about yourself and figure out how to treat people all a little better.

In commerce, the exact same rules apply. Restaurateurs train their staff in the restaurant’s voice, as it were. In a classy restaurant, the staff are extremely formal, they’re extremely polite, they’re bowing and scraping, they are your willing servants. Every wish is their command. Yes, sir. How is your meal, sir? When you go into a diner, it’s a much more friendly, welcoming, casual atmosphere. It’s like they’re your buddies. They just want you to be happy. It’s like you’re their houseguest, almost. And both of them illustrate this power disparity between the customer and the server, because the paying customer has all the power. I mean, the paying customer is literally holding money in the hope that the server is polite to them, and is nice to them and gives them a good meal. And obviously the restaurant wants that money, so they’re acting out this play where the restaurateur is making you feel special by the way that they speak to you.

In the classy restaurants, the norm is that the customer has significantly more power than the staff do. In a classy restaurant where you’re paying hundreds of dollars for a meal, the customer has way more economic, political, and social power than the server does. Although, in a diner where the norm is that the customer is closer economically and politically to the server, that means that the server can be a little more familiar. They can be a little more friendly, because they know that they have some things in common.

This is Vancouver, BC. This is a beautiful town. While I was there, I learned what happens when you break expectations, when you take that expectation around how servers are supposed to treat customers and turn it upside down. There’s a restaurant in Vancouver called Elbow Room. And I think there’s a restaurant in every town called Elbow Room, but the one in Vancouver is a diner where the staff are rude to you. They’re just kind of short with you, they’re a little surly. And when they give you your cup of water, they point in the corner and show you where the refills are. Because you get your own damn refills. The same with your coffee. They’ll bring you your first coffee; get your own refills.

They just take your order, they take it to the kitchen, and it’s their entire job to just ferry food between the table and the kitchen. They’re not trying to be nice to you. They’re not hovering over you making sure you’re happy with every aspect of your meal. So it’s a diner but it has this attitude of being a dive bar. It’s like the people who work there are all way cooler than you and they’re looking down at you for being there. They wish you weren’t there. And the staff, they’re judging you almost on how you participate in this subversive cultural experiment, which as a mismatch for your expectations is kind of interesting. It’s given them a reputation. The only reason I was there at all is because a friend told me there’s a restaurant in town where the staff are rude. And I thought, that’s really weird. I have to check this out. There’s this unique, marketable position that they’ve taken as being the rude restaurant.

So you have to think with your users, with your customers, what is your actual relationship? Are they your gods? Are they your guests? Are they a nuisance to you? Because you know where the power is. If they depend on you, if you run a monopoly, or if your product has high switching costs, you know that you have all the cards. If there are low switching costs from your product to any competitor’s product, then they have all the power. You have to keep them happy, otherwise they’ll jump ship. This is like the difference between a power company or a Twitter client.

But the power relationship that exists, versus the power relationship that you expose with your language don’t have to be the same thing. That’s a design decision that is on you. You might need to bow and scrape to keep your customers and users extremely happy, but you don’t have to act that way. You can play it cool.

The second ingredient of diatypes is the subject. Because when we know a little about something, we use very very different language to when we’re ignorant of something. We have this highly specialized vocabulary when we know a lot about a topic, and in tech we call that jargon. But it exists in all subject areas. Anywhere you can be an expert at something. In medicine or sports or law, they have jargons.

In law in particular… Who here has been in a contract dispute or has filed a patent and has had to deal with lawyers? Lawyers speak this very weird variant of the English language called legalese. And it’s a diatype that only lawyers and judges really understand, and certainly only lawyers and judges can write. And it’s not its own language, it’s not even a dialect. These lawyers don’t go home and speak this to their kids. They only use it on the job. It is entirely situational, and what’s unique about legalese is that it doesn’t evolve the way that normal language does.

Normal language is just a big popularity contest. Phrases come into fashion, some phrases go out of fashion, and that’s why they have to revise the dictionary all the time. But legalese evolves in battle, and it’s evolved by fiat. So when a lawyer writes a patent or writes a contract, they are basically putting down a record of what they think ought to happen and they write it down to the best of their abilities. If some other lawyer somewhere in the world disagrees with them, say a client’s lawyer wants to get out of a contract, or a different lawyer wants to break a patent, they’re going to go to court for that and the other lawyer’s going to try to find ways to destroy the language that they’ve written down. They’re looking for loopholes, they’re looking for weaknesses that they can convince a judge to invalidate the patent, invalidate the contract.

So after the lawyers have presented all their arguments, the judge decides whether what has been written is legally enforceable. At the end of that, that’s a precedent. So future generations of lawyers know about all these precedents, and they write their contracts accordingly. They avoid the language that they know has been defeated in court before, and they use the language that they know has been held up in court before. And that’s what makes legalese so ridiculous. We’re dealing with hundreds and hundreds of years of legal precedent that makes the language even more ridiculous and twisty as we go along. Because in every court case, plainer language went to court and lost.

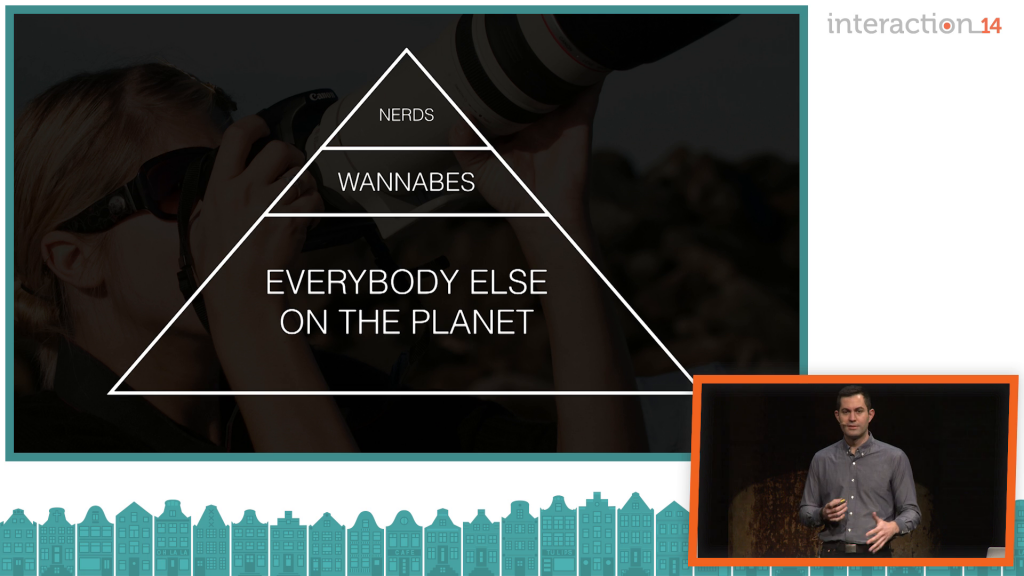

So there’s jargon in all areas of interest, all knowledge domains. Legalese is just particularly egregious because it almost doesn’t represent English at all. But you talk about food, you talk about wine, you talk about music…people have these highly-developed vocabularies. If you take professional photographers—I’m sure many of you are pros or prosumers—you talk about shutter speed, you talk about ISO and aperture and light balance, and these words are like little membership badges. They say that you’re in the I‑know-how-this-stuff-works group. And it shows who’s in the club of experts.

But for any area of interest, any subject domain in the world, you have these experts, you have enthusiasts, and then you have everybody else. So point and shoot cameras ignore everyone at the top of this pyramid. Point and shoot cameras have one button, and they don’t tell you anything about the ISO. They hide all the jargon, and in doing so they kind of thumb their noses at the experts of the world, and experts thumb their noses in return.

When you’re working on your products, you have a choice of how your address your customers. You can use language that talks to the experts, and talks to the enthusiasts (who are just experts in training), and in doing so you alienate the majority a little. You use very complex language and it scares people away. Or you can embrace the majority. You can embrace those seven billion people who don’t know anything about your area of expertise, and leave the experts unimpressed in the process. We see that a lot in the market, where products like the iPhone, they don’t don’t say anything about the megahertz, they don’t say anything about the gigabytes. All we know is that every year the iPhone gets better. We don’t know that it’s measurably better. We cannot make technical spec comparisons, really. But in doing so they’ve made computing accessible to way more than just the nerds of the world.

And this is a difficult tightrope to walk, because it’s really easy for engineering language to sneak into the user experience. It’s really easy for legal language to sneak into the user experience because when lawyers come to you saying that they needs these terms of service built into the app, you know, they’re lawyers. You freak out a little and you put it in there even though no one will understand it, ever.

But how much of this stuff you expose to your customers is a design decision. So there’s this third ingredient to diatypes that is the medium. It’s the idea that the method of communication, as well as other things, impact what you say, how you say it. In spoken conversation, when two people meet and start talking, the first thing they do is size each other up. They look at each other and they figure out which one of them is more powerful and who’s going to get more respect out of the conversation, and they evaluate each other for expertise to figure out how much technical language they can use when they’re talking to each other.

If they misjudge that, then they make asses of themselves. You talk a little too expertly to somebody who’s a complete amateur, and you’ve just made a little bit of an ass of yourself. But you recover. During the conversation, there are rules. There are these unwritten social rules about length and turn-taking, which are fascinating. If someone is talking, there is a certain length at which they shouldn’t talk anymore. They need to hand it over to the other person. And if they do, they pause for a second, the other person can take the conch and start talking, or the other person can just bounce it right back by just kind of nodding or they can just say, “Uh huh,” and that signals that they don’t want their turn. They bounce the turn back to the other person. But these turn-taking rules are part of what polite conversation is built on. So if you flaunt those rules, again, you make an ass of yourself.

But spoken conversation is extremely flexible. You can make a lot of syntactic mistakes, you can lotta make a—make a lot of grammatical errors like I’m doing right now, and you could just recover from them. You can easily make jokes. You can start sentences and just trail off and change the subject, and you can get away with it because speech is an extremely forgiving medium.

Writing is not. There is no turn-taking in writing. If somebody doesn’t get what you’re saying, they just have to keep reading and hope that they get it by the end. Journalists and academics and scientists, when they’re writing, they’re putting their thoughts down on the permanent record. And that’s kind of cool that they’re creating a little time capsule of their brain that can then travel around the world and be read by someone twenty years in the future. That’s something you cannot do with conversation.

So when they’re writing these things, they need to be clear and they need to be exhaustive so that there are no questions left unanswered. But then they need to be factual, and then they try to be formal. They try to be as formal as they can. They try to hone in on standard English. And earlier when I said there is no standard English because it’s all just a mess of dialects, they hone in on standard English that I’ll call “English teacher English,” the lowest common denominator of the English language. The hope is with this, especially for scientists, that in a hundred years people will still be able to understand it because you’re not using any slang, you’re not using any weird swear words, you’re not using anything that’s culturally relevant right now. You’re using stuff that will hopefully persist. Because that’s the idea use case for a scientist when they’re writing; they write their paper, and in a hundred years people are still reading it and saying, “Wow, that guy’s really smart. I’m so glad he wrote this paper a hundred years ago.”

Texting is a relatively new phenomenon. Texting is written, obviously, but it’s more conversational. You can take liberties with your punctuation, you can take liberties with your spelling, and you can get real-time feedback from the party that you’re texting with. It’s a really forgiving medium, even though it’s written. And parents and educators freak out about this a little. They think that texting might be a danger to literacy. Texting and driving is a danger to a lot of things, but texting is no more a danger to literacy than speaking is. Texting is a completely different medium, and so it’s a different diatype. And the key is teaching young people the difference between those two things, the same way that you teach them the difference between how they can write a note for their mom that they leave on the kitchen table before they go out to play, versus writing a school essay.

These are situational differences, and it’s like teaching children not to swear. When you teach a kid not to swear, you’re not trying to stop them from swearing for their entire lives. You know that you’re never going to accomplish that. You just need to teach them when it’s not okay to swear. Not in front of the teachers, not in front of the boss, not in front of your mother-in-law. Just save it for when you hit yourself on the thumb with a hammer. Everyone’ll be okay with that. It’s the situational appropriateness.

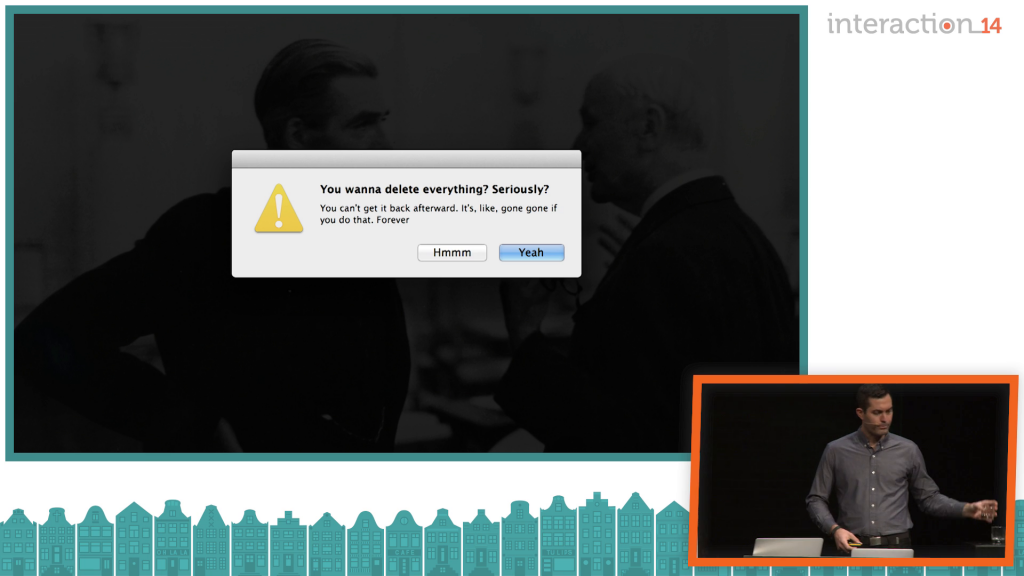

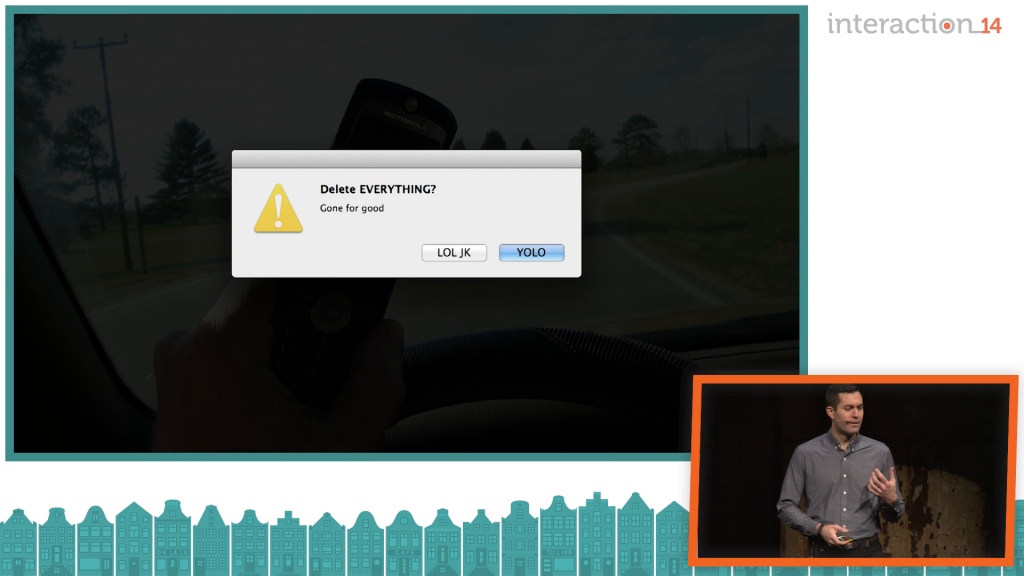

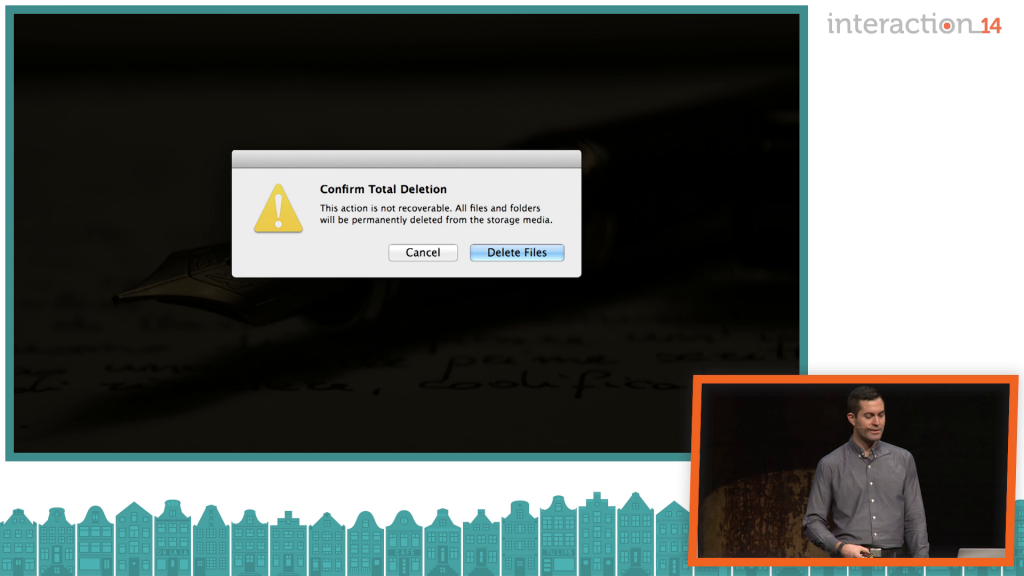

Interactive products, the products that we work on are in an interesting middle ground. Interactive is not conversation. A dialog box is not a dialogue. Even though this user has a button to respond, they can contribute to the conversation, that’s not turn-taking. You don’t have to explain everything in your dialogs because you can let people find out more information elsewhere, like you would in a conversation. Because interactive products are kind of a choose-your-own-adventure. They are one big conversation between a person and a computer system.

But we know that people won’t tolerate length. We know that people won’t read more than a couple words of this. There’s also no prosody in your writing. Prosody is the tone and the rhythm, the cadence of how you speak. And prosody is useful for sarcasm. You can’t do sarcasm without tone. You can’t use sarcasm in writing in interactive products. And humor will tend to fall flat.

But interactive isn’t texting, either. It’s written, and then it’s published. Errors in what you do, errors in punctuation, errors in spelling and basic grammar, are less forgivable in interactive products, which is kind of weird. We have this kind of desire to be more professional-looking, even as we try to be friendly as brands.

So it’s not like texting, and it’s not like writing, either. Because it’s not a publication. What you’re writing in your interactive products is not on the permanent record. Our products are fleeting. Our products are evolving. And the copy that you write today probably won’t even be there in two years. If the company is there in two years, if the product is there in two years, it may have been completely redesigned. It may have moved in a completely different direction, that feature may be completely obsolete by then.

So we’re constantly adjusting and republishing our products. We make mistakes and the we just fix them. It’s not like traditional publishing in that you don’t get to do a second edition unless you sell ten million of your first edition. You’re constantly putting out second editions. There’s always a .1 release.

So unlike an academic audience, your audience for interactive purposes is right now. You can make timely references as part of how you speak to your customers, because they won’t be there in a hundred years. You can reference a new Beyoncé album in an error dialog and then when it’s not a new album anymore, you just change the error dialog. It’ll take you five seconds. So we have to work with these strengths and weaknesses of our medium that have never really been taken into concern before. Because diatype is a design decision through and through.

Of these three ingredients in diatype, people get how relationship impacts speech just kind of intuitively. People know to be polite and professional during a job interview, but they don’t necessarily consider that they can flaunt those rules. That they can be a little cheeky, be a little rude, and it works to their favor.

People get that jargon is kind of difficult when you’re working with newbs. They don’t realize jargon’s ability to include or exclude people. Jargon has this power to create in-groups and out-groups that help people feel like they belong, or it can make people feel unwelcome, which is really kind of scary. We can address a large audience, or we can address a very small audience and make that audience feel ultra-special that we’re talking directly to them. We can communicate with them with very specific language they understand. We can appear more trustworthy and more credible for speaking to them directly, when you’re targeting a very specific slide of society.

And people understand intuitively how talking is different from writing. You show anyone a transcript of how they talk, they’ll see a lot of false starts. They’ll see a lot of ums and ahs that makes them feel weird because they would never write that. But they don’t consider that they can choose this style, that you could actually go out of your way to write an entire English essay as if it were dictated with all the ums and ahs and false starts that you want.

In university, since I was simultaneously studying linguistics and computer science, I got in a lot of trouble with my computer science professors for writing like a linguistics student. It’s like I was blogging my computer science papers. And the professors hated that, but they couldn’t mark me down for it because it was just stylistic. It was not a factual problem.

In our medium, it was not that long ago that shrink-wrapped software was only updated annually, maybe at best. Maybe every three or four years instead. Nowadays we’re shipping web sites daily, we’re shipping apps every month, and the updates are all free and automatic. They just appear. And this affords us all kinds of freedoms as designers. These are freedoms to make mistakes and fix them later, because diatype isn’t just about communication, it’s about branding. As much as color and typography are about branding. And diatype also impacts learnability and usability.

And most of all it impacts people’s emotional affect. Because we know that there’s no such thing as no design. We know that when an engineer says, “Oh, I just put this together. It hasn’t been designed,” what that really means is, “I made a bunch of design decisions without thinking.” In that same vein there’s no such thing as no diatype. There are just the diatypes that we subconsciously choose, without thinking.

And the ones that we subconsciously choose are usually about who is going to be proofreading it. When you write something for work, you’re either writing it for yourself, or your boss, or the engineers. So we have a responsibility to think more about the impacts of our words. We need to choose when we’re going to speak to our customers with respect. We’ve got to choose when we’re going to speak to them with disdain, or compassion. We can choose snobbery. We can choose jargon. All of these are design decisions.

A non-choice is just a cop-out. Because the world is full of people who don’t all talk like you. They don’t all talk like me. They don’t all talk like your peers. We didn’t have the same upbringing. We didn’t come from the same countries. We didn’t have the same education or opportunities. We don’t have the same experience with technology. And we certainly don’t have the same experience with this specific product that if you’ve been working on it for a while you’ve got all kinds of research and design background in. It’s our responsibility as designers to choose the language that we use to communicate with them wisely, for them.

So good luck, and thank you.

Further Reference

This presentation’s description and bio for Clark, at the Interaction14 site.