Introducer: Our next talk will be tackling how social media companies are creating a global morality standard through content regulations. This will be presented by the two persons standing here, the digital rights advocate Mathana, and writer and activist Julian C. York. Please give them a warm applause.

Mathana: Hello everybody. I hope you had a great Congress. Thank you for being here today. We’re almost wrapped up with with the congress, but we appreciate you being here. My name is Mathana. I am a communication strategist, creative director, and digital rights advocate focusing on privacy, social media, censorship, and freedom of the press, and expression.

Jillian C York: And I’m Jillian York and I work at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, where I work on privacy and free expression issues, as well as a few other things. I’m based in Berlin. [applause] Thank you. For Berlin? Awesome. I hope to see some of you there.

So today we’re going to be talking about sin in the time of technology, and what we mean by that is the way in which corporations, particularly content platforms and social media platforms are, driving morality and our perception of it. We’ve got three key takeaways to start off with.

The first is that social media companies have an unparalleled amount of influence over our modern communications. This we know. I think this is probably something everyone in this room can agree on.

These companies also play a huge role in shaping our global outlook on morality and what constitutes it. So the ways in which we perceive different imagery, different speech, is being increasingly defined by the regulations that these platforms put upon us [in] our daily activities on them.

And third they’re entirely undemocratic. They’re beholden to shareholders and governments, but not at all to the public; not to me, not to you. Rarely do they listen to us, and when they do there has to be a fairly exceptional amount of public pressure on them. So that’s that’s our starting point. That’s what we want to kick off with. I’ll pass the mic to Mathana.

One strong hint is buried in the fine print of the closely guarded draft. The provision, an increasingly common feature of trade agreements, is called “Investor-State Dispute Settlement,” or ISDS. The name may sound mild, but don’t be fooled. Agreeing to ISDS in this enormous new treaty would tilt the playing field in the United States further in favor of big multinational corporations.

Elizabeth Warren, “The Trans-Pacific Partnership clause everyone should oppose”

Mathana: So thinking about these three takeaways, I’m going to bring it kind of top-level for a moment, to introduce an idea today, which some people have talked about, the idea of the rise of the techno class. Probably a lot of people in this room have followed the negotiations leaked in part and then in full by WikiLeaks about the Trans-Pacific Partnership, the TPP. What some people have mentioned during this debate is the idea of a corporate capture, a world now in which the corporations are becoming, are maturing to the to the extent in which they can now sue governments, that the multinational reach of many corporations [is] larger than that, the diplomatic reach of countries. And with social media platforms being part of this, the social media companies now are going to have the capacity to influence not only cultures but people within cultures, and how they communicate with people inside their culture, and communicate globally. So as activists and technologists, I would like to propose at least that we start thinking about and beyond the product and service offerings of today’s social media companies and start looking ahead to two, five, ten years down the road, in which these companies may have social media services and social media service offerings which are indistinguishable from today’s ISPs and telcos and other things. And this is really to say that social media is moving past the era of the walled garden into neo-empires.

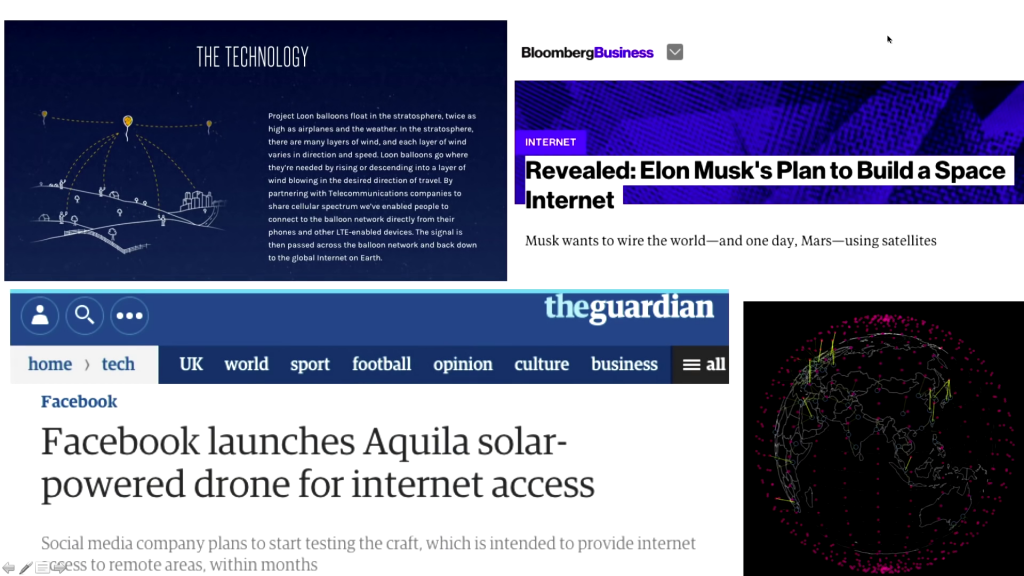

Pictured: Project Loon, “Revealed: Elon Musk’s Plan to Build a Space Internet”, “Facebook launches Aquila solar-powered drone for internet access”

One of the things that’s on this slide are some headlines about different delivery mechanisms in which the social media companies and people like Elon Musk are looking to roll out and almost leapfrog, if not completely leapfrog, the existing technologies of terrestrial broadcasting, fiber optics, these sort of things. So now we’re looking at a world in which Facebook is now going to have drones, Google is looking into balloons, and other people are looking into low Earth orbit satellites, to be able to provide directly to the end consumer, to the user, to the handset, the content which flows through these networks.

So one of the first things I believe we’re gonna see in this field is free basics. Facebook has a service (it was launched as Internet.org and now has been rebranded to Free Basics), and why this is interesting is that in one hand Free Basics is a free service that is trying to get people that are not on the Internet now to use Facebook’s window to the world. It has maybe a couple dozen sites that are accessible. It runs over the data networks for countries. Reliance, a telecommunications company in India is one of the larger telcos, but not the largest. There’s a lot of pressure that Facebook is putting on the government of India right now to be able to have this service offered across the country.

One of the ways that this is problematic is because a limited number of websites flow through this, that people that to get exposed Free Basic, this might be their first time seeing the Internet in some cases. An example that’s interesting think about is a lion born into a zoo. Perhaps evolution and other things may have this lion dream of perhaps running wild on the plains of Africa, but at the same time it will never know that world. Facebook Free Basic users, knowing Facebook’s window of the Internet, may not all jump over to a full data package on their ISP, and many people may be stuck in Facebook’s window to the world.

Meanwhile, the postings, pages, likes, and friend requests of millions of politically active users have helped to make Zuckerberg and colleagues very rich. These people are increasingly unhappy about the manner in which Facebookistan is governed and are taking action as the stakes continue to rise on all sides.

Rebecca MacKinnon, “Ruling Facebookistan”

York: In other words, we we’ve reached an era where these companies have, as I’ve said, unprecedented control over our daily communications. Both the information that we can access, and the speech and imagery that we can express to the world and to each other. So the postings and pages and friend requests of millions of politically active users as well have helped to make Mark Zuckerberg and his colleagues, as well as the people at Google and Twitter and all these other fine companies extremely rich. And yet we’re pushing back. In this case I’ve got a great quote from Rebecca MacKinnon where she refers to Facebook as Facebookistan, and I think that that is an apt example of what we’re looking at. These are corporations but they’re not beholden at all to the public, as we know, and instead they kind of turned into these quasi-dictatorships that dictate precisely how we behave on them.

The U.S. Internet market remains too big to ignore, as a result of which products are typically tailored to suit the speech norms of this market and have been tailored in this manner for almost two decades.

Ben Wagner, “Governing Internet Expression: How Public and Private Regulation Shape Expression Governance”, Journal of Information Technology and Politics, Volume 10, Issue 4, 2013

I also wanted to throw this one up to talk a little bit about the global speech norm. This is from Ben Wagner, who’s written a number of pieces on this but who can of course the the concept of a global speech standard, which is what these companies have begun and and are increasingly imposing upon us. This global speech standard is essentially catering to everyone in the world, trying to make every user in every country and every government happy, but as a result of kind of tampered down free speech to the this very basic level that makes both got the governments of let’s say the United States and Germany happy, as well as the governments of countries like Saudi Arabia. Therefore we’re looking at really kind of the lowest common denominator when it comes to some types of speech, and this sort of flat, grey standard when it comes to others.

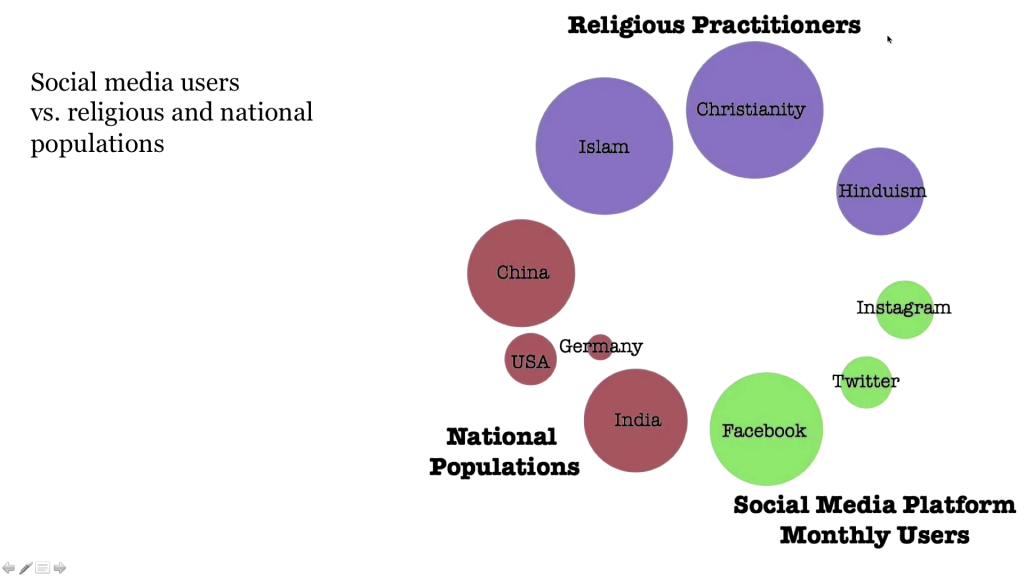

Mathana: So as Jillian just mentioned, we have countries in play. Facebook and other organizations, social media companies are trying to pivot and play with an international field, but let’s just take for a moment a look at the scale and scope and size of these social media companies.

I just pulled some figures from the Internet, and with some latest census information. We have China, 1.7 billion people. India, 1.25 billion people. 2.2 billion individuals and practice of Islam and Christianity. But now we have Facebook with, according to their statistics, 1.5 billion active monthly users. Their statistics; I’m sure many people here would like to dispute these numbers, but at the same time these platforms are now large. I mean not larger than some of the religions, but Facebook has more monthly active users than China or India have citizens. So we’re not talking about basement startups, we’re now talking about companies with the size and scale to be able to really be influential in a larger institutional way.

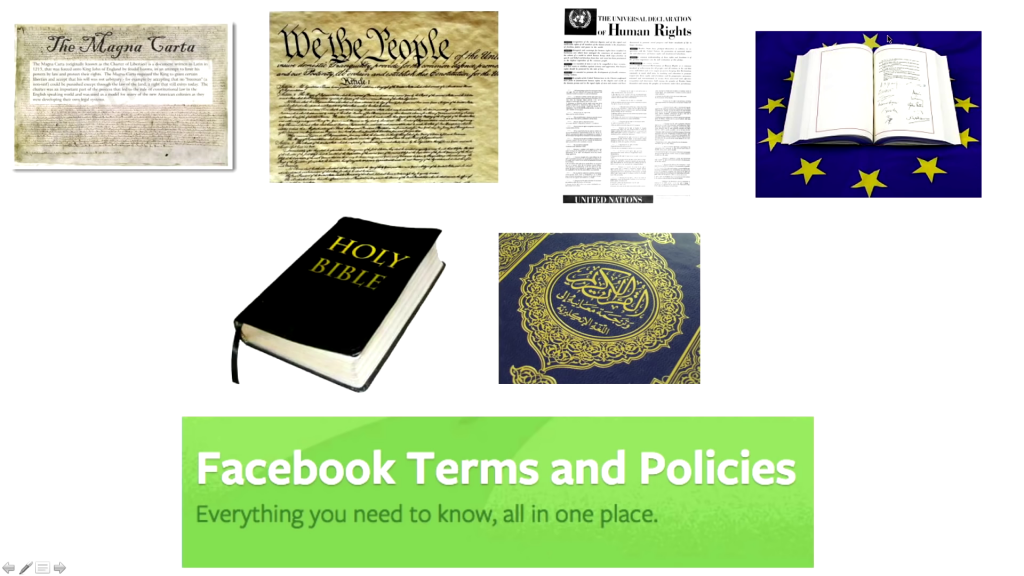

Magna Carta, the US Constitution, the Declaration of Human Rights, the Treaty of Maastricht, the Bible, the Koran. These are time-tested, at least long-standing, principal documents that place upon their constituents, whether it be citizens or spiritual adherents, a certain code of conduct. Facebook, as Jillian mentioned, mentioned is non-democratic. Facebook’s terms and standards were written by a small group of individuals with a few compelling interests in mind, but we are now talking about 1.5 billion people on a monthly basis that are subservient to a terms of service which they had no input on.

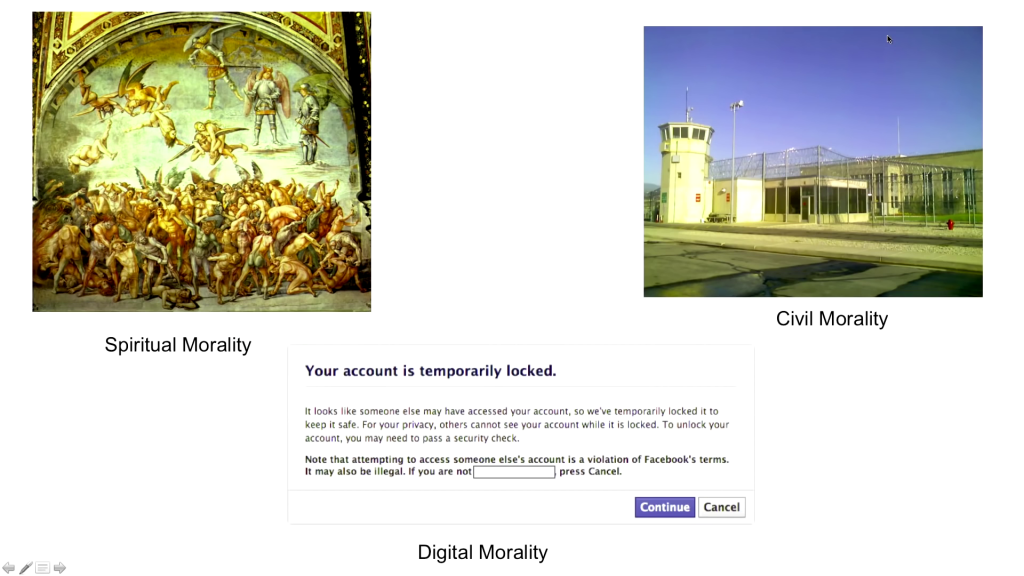

So to pivot from there and bring it back to spirituality, why is this important? Well, spiritual morality has always been a place for religion. Religion has a monopoly on the soul, you could say. Religion is a set of rules which if you obey, you are able to not go to hell or have an afterlife, [be] reincarnated, whatever the religious practice may be. Civil morality is quite interesting in the sense that the sovereign state as a top-level institution has the ability to put into place a series of statutes and regulations, the violation of which can send you to jail. Another interesting note is that the state also also has a monopoly on the use of sanctioned violence. Say that the official actors of the states are able to do things which the citizens of that state may not. And if we take a look at this concept of digital morality I spoke about earlier, with services like Free Basic introducing new individuals to the Internet, well by a violation of the terms of service, you can be excluded from from these massive global networks. And Facebook is actively trying to create if not a monopoly, a semi-monopoly on global connectivity in a lot of ways.

So what what drives Facebook? And this is a few things. One is a protectionistic legal framework. The control of copyright violations is something that a lot of platform stomped out pretty early. They don’t want to be sued by the RIAA or the MPAA, and so there were mechanisms in which copyrighted material was able to be taken out of the platform. They also limit potential competition. And I think this is quite interesting in the sense that they’ve shown this in two ways. One, they’ve purchased rival or potential competitors. You see this with Instagram being bought by Facebook. But Facebook has also demonstrated the ability or shown the willingness to censor certain content. tsu.co is a new social site, and mentions and links to this platform were deleted or not allowed on Facebook. So even using Facebook as a platform to talk about another platform was not allowed. And then a third component is the operation on a global scale. It’s not only the size of the company but it’s also about the global reach. Facebook maintains offices around the world, as other social media companies do. They engage in public diplomacy, and they also operate in many countries and many languages.

So just to take it to companies like Facebook for a moment. If we’re looking at economics, you have the traditional twentieth-century multinationals, Coca-Cola, McDonald’s. The goal for the end user of these products was consumption. This is changing now. Facebook is looking to capture more and more parts of the supply chain, and as a service provider, as a content moderator, and responsible for negotiating and adjudicating the content disputes. At the end of the day users are really the product. It’s not for us Facebook users, the platform, it’s really for advertisers. And [if] we take a hierarchy of the platform, we have the corporation, advertisers, and then users kind of at the fringes.

Pictured: “Inside Facebook’s Outsourced Anti-Porn and Gore Brigade, Where ‘Camel Toes’ are More Offensive Than ‘Crushed Heads’ ”, “The Laborers Who Keep Dick Pics and Beheadings Out of Your Facebook Feed”

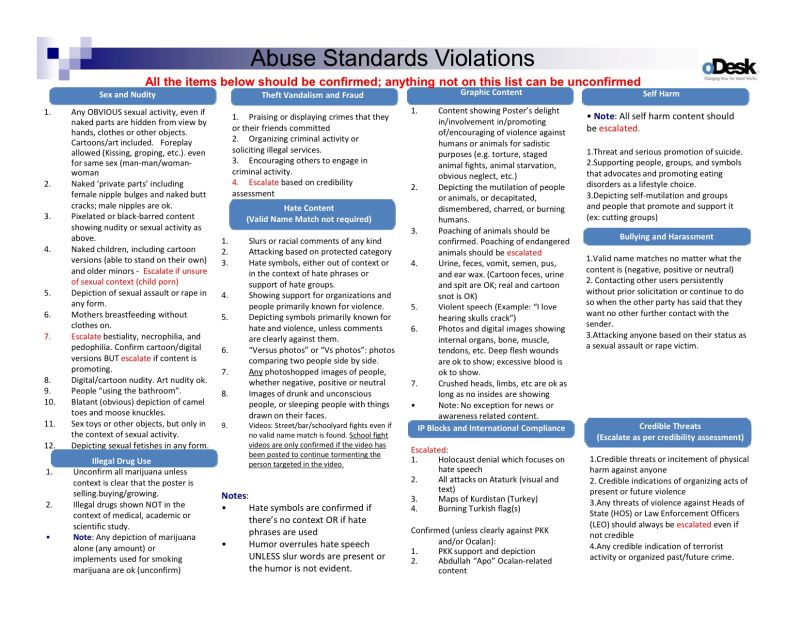

York: So let’s get into the nitty gritty a little bit about what content moderation on these platforms actually looks like. I’ve put up two headlines from Adrian Chen, a journalist who wrote these for Gawker and Wired respectively. They’re both a couple years old. But what he did was he investigated who was moderating the content on these platforms. And what he found and accused these companies of is outsourcing their content moderation to low-paid workers in developing countries. In the first article I think Morocco was the country, and I’m going to show a slide from that a bit, of what those content moderators worked with. And the second article talked a lot about the use of workers in the Philippines for this purpose. We know that these workers are probably low-paid. We know that they’re given very very minimal time frame to look at the content that they’re being presented.

So here’s how it basically works across platforms, with small differences: I post something. (And I’ll show you some great examples of things I posted later.) I post something, and if I post it to my friends only, my friends can then report it to the company. If I post it publicly, anybody who can see it, or who’s a user of the product can report it to the company. Once a piece of content is reported, a content moderator then looks at it and within that very small time frame (we’re talking half a second to two seconds, probably, based on the investigative research that’s been done by a number of people) they have to decide if this content fits the terms of service or not.

Now, most of these companies have a legalistic terms of service as well as a set of community guidelines or community standards which are clear to the user, but they’re still often very vague, and so I want to get into a couple of examples that show that.

Image: Gawker

This slide is one of the examples that I gave. You can’t see it very well, so won’t leave it up for too long, but that was what content moderators at this outsource company, oDesk, were allegedly using to moderate content on Facebook.

This next photo contains nudity.

Image: Paper

I think everyone probably knows who this is and has seen this photo. Yes? No? OK. This is Kim Kardashian, and this photo allegedly broke the Internet. It was a photo taken for Paper Magazine. It was posted widely on the Web, and it was seen by many many people. Now, this photograph definitely violates Facebook’s Terms of Service, buuut Kim Kardashian’s really famous and makes a lot of money, so in most instances as far as I could tell, this photo was totally fine on Facebook.

We restrict the display of nudity because some audiences within our global community may be sensitive to this type of content — particularly because of their cultural background or age.

Facebook Comunity Standards, accessed January 13, 2016, (bolding added)

Now let’s talk about those rules a little bit. Facebook says that they restrict nudity unless it is art. So they do make an exception for art which may be why they allowed that image of Kim Kardashian’s behind to stay up. Art is defined by the individual. And yet at the same time they make clear that let’s say a photograph of Michelangelo’s David or a photograph of another piece of art in a museum would be perfectly acceptable, whereas your sort of average nudity maybe probably is not going to be allowed to remain on the platform.

They also note that they restrict the display of nudity because their global community may be sensitive to this type of content, particularly because of their cultural background or age. So this is Facebook, in their community standards, telling you explicitly that they are toning down free speech to make everyone happy.

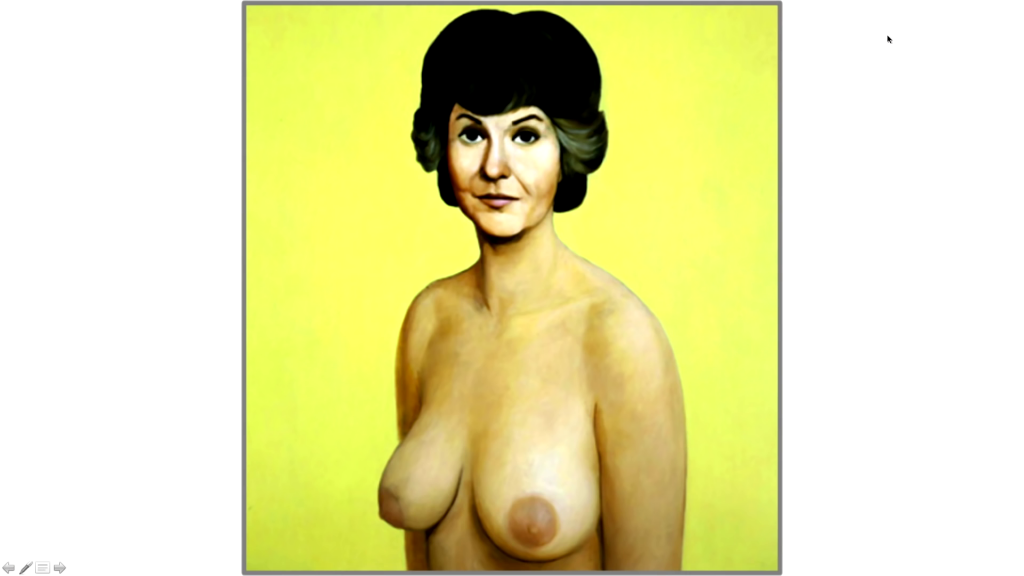

This is another photograph. Germans particularly, I’m interested to see, is everyone familiar with the show The Golden Girls? Quite a few. So you might recognize her. She was Dorothy in The Golden Girls. This is the actress Bea Arthur, and this is from a painting from 1991 by John Curran of her. It’s unclear whether or not she sat for the painting. It’s a wonderful image. It’s beautiful. It’s a very beautiful portrait of her. But I posted it on Facebook several times in a week. I encouraged my friends to report it, and in fact Facebook found this to not be art. Sorry.

Another image. This is by a Canadian artist called Rupi Kaur. She posted a series of images in which she was menstruating. She was trying to essentially describe the normal the normality of this, the fact that this is something that all women go through. Or most women go through, rather. And as a result, Instagram: denied. Unclear on the reasons. They told her that it had violated the terms of service but weren’t exactly clear as to why.

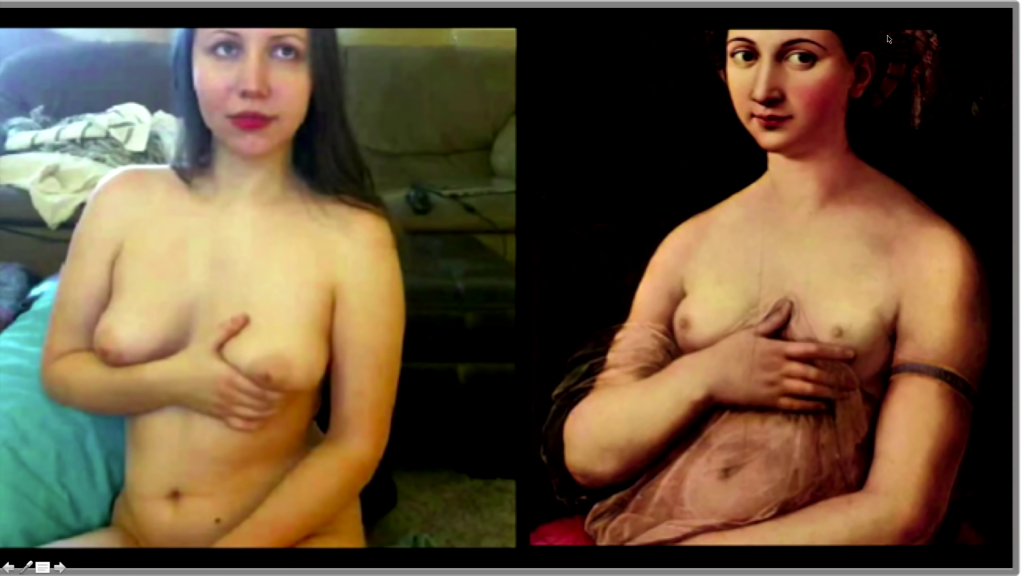

“sexcutrix as La Fornarina, Raphael” from Webcam Venus, by Addie Wagenknecht & Pablo Garcia

And finally this is another one. This was by an artist friend of mine. I’m afraid that I have completely blanked on who did this particular piece, but what it was is they took famous works of nude art and had sex workers pose in the same poses as the pieces of art. I thought it was a really cool project. But Google+ did not find that to be really cool project, and because of their guidelines on nudity they banned it.

This is a cat. Just wanted to make sure you’re awake. It was totally allowed.

“Diversity” at social media companies

Facebook: 68% men globally. In the US, 55% white.

Twitter: 66% men globally. In the US, 59% white.

Google: 70% men globally. In the US, 60% white.

[presentation slide]

In addition to the problems of content moderation, I’m going to say that we also have a major diversity problem at these companies. These statistics are facts. These are from all of these companies themselves. They put out diversity reports recently, or as I like to call them “diversity” reports. The statistics are a little bit different because they only capture data on ethnicity or nationality in their US offices, just because of how those standards are sort of odd all over the world. So the first stats refer to their global staff; the second ones in each line refer to their US staff. But as you can see these companies are largely made of white men, which is probably not surprising, but it is a problem.

Now why is it a problem, particularly when you’re talking about policy teams? The people who build policies and regulations have an inherent bias. We all have an inherent bias. But what we’ve seen in this is really a bias of sort of the American style of prudeness. Nudity is not allowed, but violent extreme violence as long as it’s fictional is totally OK. And that’s generally how these these platforms operate. And so I think that when we ensure that there is diversity in the teams creating both our tools, our technology, and our policies, then we can ensure that diverse worldviews are brought into those that creation process, and that the policies are therefore more just.

So what can we do about this problem as consumers, as technologists, as activists, as whomever you might identify as?

The first one I think a lot of the technologists are going to agree with: develop decentralized networks. We need to work toward that ideal because these companies are not getting any smaller. I’m not going to necessarily go out and say that they’re too big to fail, but they are massive and as Mathana noted earlier they’re buying up properties all over the place and making sure that they do have control over our speech.

The second thing is to push for greater transparency around terms of service takedowns. Now, I’m not a huge fan of transparency for the sake of transparency. I think that these companies have been putting out transparency reports for a long time that show what countries ask them to take down content or hand over user data. But we’ve seen those “transparency” reports it to be incredibly flawed already. So in pushing for greater transparency around terms of service takedowns, that’s only a first step.

The third thing is we need to demand that these companies adhere to global speech standards. We already have the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. I don’t understand why we need companies to develop their own bespoke rules. [applause] And so by demanding that companies adhere to global speech standards, we can ensure that these are places of free expression. Because it is unrealistic to just tell people to get off Facebook. I can’t tell you how many times in the tech community over the years I’ve heard people say, “Well, if you don’t like it just leave.” That’s not a realistic option for many people around the world and I think we all know that deep down.

And the other thing I would say there, though, is that public pressure works. We saw last year with Facebook’s real name policy there were a number of drag performers in the San Francisco Bay Area who were kicked off the platform because they were using their performance, their drag names. Which is a completely legitimate thing to do just as folks have hacker names or other pseudonyms, but those folks pushed back, they formed a coalition, and they got Facebook to change a little bit. It’s not completely there yet, but they’re making progress and I’m hoping that this goes well.

And the last thing (and this is totally a pitch; throwing that right out there), support projects like ours, which I’m going to throw to Mathana to talk about, onlinecensorship.org, and another project done by the excellent Rebecca MacKinnon called Ranking Digital Rights.

Mathana: So just a little bit of thinking outside the box. onlinecensorship.org is a platform that’s recently launched. Users can go onto the platform and submit. There’s a small questionnaire if their content has been taken down by the platforms. Why we think this is exciting is because right now, as Jillian mentioned, that transparency reports are are fundamentally flawed, we are looking to crowdsource information about the ways in which six social media companies are moderating and taking down content. Because we can’t know exactly their accountability and transparency in real time, we’re hoping to be able to find trends both across the kind of content that has been taking down, geographic trends, news related trends, within sort of self-reported content takedown. But it’s platforms like these I think that hopefully will begin to spring up in response, for the community to be able to put tools in place, that people can be a part of the reporting and transparency initiative.

York: We launched about a month ago, and we’re hoping to put our first set of reports around March.

It is reasonable that we press Facebook on these questions of public responsibility, while also acknowledging that Facebook cannot be all things to all people. We can demand that their design decisions and user policies be explicit, thoughtful, and open to public deliberation. But the choices Facebook makes, in their design and in their policies, are value judgments.

Jessa Lingel & Tarleton Gillespie, “One Name to Rule Them All: Facebook’s Identity Problem”

And finally, I just want to close with one more quote before we slip into Q&A, and that is just to say that it’s reasonable that we press Facebook on these questions of public responsibility while also acknowledging that Facebook cannot be all things to all people. We can demand that their design decisions and user policies be explicit, thoughtful and open to public deliberation. But, and this is the most important part in my view, the choices that Facebook makes in their design and in their policies are value judgments. This is political, and I know you’ve heard that a lot of talks. So have I. But I think we can’t we cannot forget that this is all political, and we have to address it as such. And for someone, if that means quitting the platform, that’s fine too, but I think that we should still understand that our friends, our relatives, our families, are using these platforms and that we do owe it to everybody to make them a better place for free expression and privacy.

Thank you.

Audience 1: You just addressed it. I’m sort of, especially after listening to your talk, I’m sort of on the verge of quitting Facebook or starting to. I don’t know. And I agree it’s a hard decision. I’ve been on Facebook for I think six years now, and it is a dispute for me, myself. So I’m in this very strange position and now I have to decide what to do. Is there any help for me out there that takes my my state and helps me deciding? Or I don’t know. It’s strange.

York: That’s such a hard question. I’ll put on my privacy had for just a second and and say what I would say to people when they’re making that consideration from a privacy viewpoint, because I do think that the implications of privacy on these platforms is often much more severe than those of speech. But this is what I do. So in that case I think it’s really about understanding your threat model. It’s understanding what sort of threat you’re under when it comes to the data collection that these companies are undertaking, as well as the censorship, of course. But I think it really is a personal decision and I’m sure that there are great resources out there around digital security and around thinking through those threat model processes, and perhaps that could be of help to you for that. I don’t know if you want to add…

Mathana: I think it’s one of these big toss-ups. This is a system which many people are connected through, even sometimes email addresses roll over, so I think it’s the opportunity cost. By leaving a platform, what do you have to lose, what you have to gain? But it’s also important to remember how the snapshot we see a Facebook now, it’s probably not going to get better. It’s probably going to be more invasive and coming into different parts of our lives. So I think from the security and privacy aspect, it’s really just up to the individual.

Audience 1: Short follow-up, if I’m allowed to. The main point for me is not my personal implications. So I am quite aware that Facebook is a bad thing and I can leave it. But I’m sort of thinking about it’s way past the point where we can decide on our own and decide, “Okay, is it good for me, or is it good for my friend, or is it good for my mom and my dad or whatever?” We have to think about is Facebook as such a good thing for the society, as you’re addressing. So I think we have to drive this decision-making from one person to a lot lot lot of persons.

York: I agree. And I’ll note what we’re talking about and the project that we’re working on together is a small piece of the broader issue, and I agree that this needs to be tackled from many angles.

Audience 2: One of the questions from the internet is, aren’t the moderators the real problem, who ban everything which they don’t really like, rather than the providers of service?

York: I would say that the content moderators, we don’t know who they are. So that’s part of the issue. We don’t know, and I’ve heard many allegations over the years when certain content’s been taken down in a certain local or cultural context. Particularly in the Arab world, I’ve heard the accusation that, “Oh, those content moderators are pro-Sisi,” (the dictator in Egypt) or whatever. I’m not sure how much merit that holds, because like I said we don’t know who they are. But what I would say is that it doesn’t feel like they’re given the resources to do their jobs well. So even if they were the best, most neutral people on earth, they’re given very little time, probably very little money, and not a whole lot of resources to work with in making those determinations.

Audience 3: First off, thank you so much for the talk. I just have a basic question. It seems logical that Facebook is trying to put out this mantra of “protect the children.” I can kind of get behind that. And it also seems, based on the fact that the have the “real names policy,” that they would also expect you put in a real legal age. So if they’re trying to censor things like nudity, why couldn’t they simply use things like age as criteria to protect children from nudity, while letting everyone else who is above the legal age make their own decision?

York: Do you want to take that?

Mathana: I think it’s a few factors. One is on the technical side, what constitutes nudity? And in a process way, if it does get flagged, do you have some boxes to say what sort of content? I could see a system in which content flagged as nudity gets referred to a special nudity moderator, and then if the moderator says yes this is nudity then filter all less than legal age or whatever age. But I think it’s part of a broader, more systematic approach by Facebook. It’s the broad strokes. It’s really kind of dictating this digital morality baseline, and saying, “No. Anybody in the world cannot see this. These are our hard lines, and it doesn’t matter what age you are or where you reside, this is the box which we are placing you in, and content that falls outside of this box, for anybody regardless of age or origin, this is what we say you can see, and anything falls out [of] that, you risk having your account suspended.” So I think it’s a mechanism of control.

Further Reference

This presentation page at the CCC media site, with downloads available.