Lee Rainie: Good afternoon, everyone. Thank you so much for coming. It’s an honor for me to be here. I’m Lee Rainie. I direct Internet science and technology research at the Pew Research Center, which is, we call ourselves a “fact tank” in Washington, DC. I have a connection to Elon because I have a daughter who went here and graduated in 2003. And I stay connected with the communications school because I love it, because they listen to me when I give them advice, and because I have a special relationship with the faculty there, especially professor Janna Anderson. She and I have done work about the future— Yay for Janna!

We are now completing our seventh round of interviewing of experts. We began in 2004, asking them about the future of the Internet. And we just completed the gathering of our data for the seventh time this summer, and we’ll be issuing reports later on this year about some of the worries that people have about the future of the Internet.

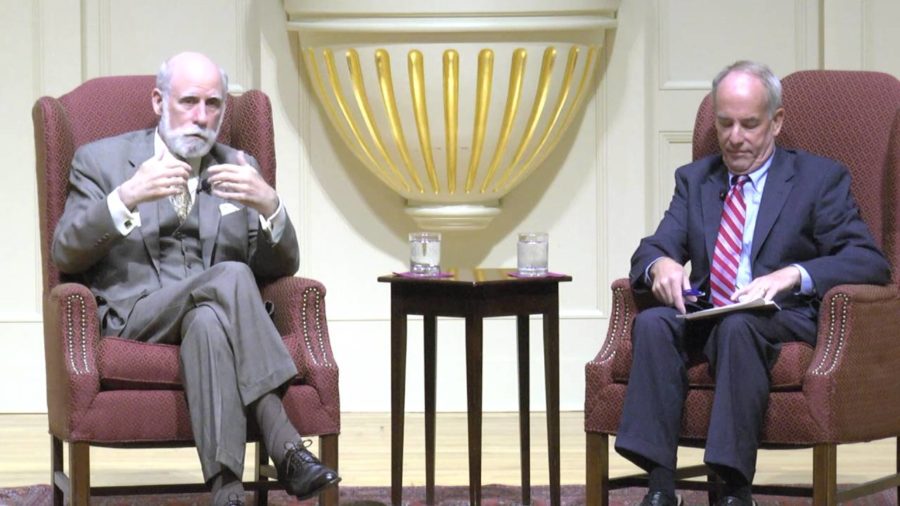

But mostly it’s my pleasure here to be with a real hero of mine and a person who should be a hero to all of you, Dr. Vint Cerf. [applause]

Vint Cerf: Thank you.

Rainie: He and his friend Bob Kahn invented the transfer protocols that essentially made the Internet the Internet. And he’s special to me because he is the only inventor that I can ever think (and I’ve checked this on Google, so it must be true because he’s a Vice President at Google), he’s the only inventor of a major technology who has through the rest of his lifetime been concerned about the impact of that technology and tried to design or redesign ways to make it better to serve humanity. I literally don’t know of any inventor who’s cared that much about his creation in that way. They want to make more money oftentimes. They want to make a better light bulb sometimes. But he has tried to make the world a better place continually by thinking about how the impact of his machinery. So we owe him those thanks, too.

And my final thanks to him are, when I went to the Pew Charitable Trust to get the grant that I did, I had to do some fact-finding about what we should do to study the impact of the Internet. And he took my phone call and sat with me for two hours in his office, unlike a lot of people, because I was a nobody who knew nothing in those days. And he sat with me and helped really think about a research design for the earliest years of my project starting in 2000.

And five things came out of that conversation. Four pieces of immediate research that we did. You probably don’t even remember this. You encouraged me to research the social impact of the Internet. So literally there were questions at that time about whether we were losing our humanity when we were starting to communicate virtually.

The second thing you encouraged me to do was to study the impact of computer viruses on the world, because they were beginning to become a persistent part of the Internet. Nobody was documenting them, and you said that would be a good thing to do.

Then you cared a lot about privacy, and what was going on. And you cared a lot about the impact that the Internet in healthcare. And those are the first four pieces of research that we did.

You also had the germ of the idea about the Future of the Internet project. You said there’s so much around the horizon. I have my thoughts about it, but other people have their thoughts. Why don’t you study that, too?

So, thank you. Because you’re really the inspiration for the communication school’s Imagining the Internet program that survives still, and will have a much bigger, prominent role in the new communications program.

Cerf: So, just to place this in time context, this would have been around 2000, is that right?

Rainie: Yeah, 1999. July 1999.

Cerf: So this is just as the Dot Boom is peaking, which is one reason why this would be an interesting thing to study, whereas the Dot Bust came in April of 2000. But the Internet continued to grow despite that. The bust was all about investors throwing money at Internet, at people who didn’t really have a business model. It was just one of those “maybe something will stick.” And so even though that bust happened, the Internet continued to grow because of its utility. And of course today, sixteen years later, you see what you what you see now, which is that 50% of the world’s population [is] online.

Of course, as the Chief Internet Evangelist at Google, my job is to get the other three and a half billion people online. So Eric Schmidt, who’s the Executive Chairman of Google told me I wasn’t allowed to retire because I’m only half done.

Rainie: Nice. Let’s move right into perhaps the thorniest question about the Internet’s impact, particularly in the generation to come. And it relates to the way that digital material—robotics, artificial intelligence, and other innovations—are going to mess with the current job situation. Millions of people who currently are employed will see technology replace the functions that they now perform for pay. There will be innovations that create new kinds of jobs. I know you’re thinking a lot about this and have just published your thoughts on this. So, could you tell us why we shouldn’t be worried?

Cerf: Well, I don’t think that I would tell you shouldn’t be worried. I think we should be thoughtful about this. First of all, if you go to a web page called i4j.info (it’s Innovation For Jobs, effectively, .info) there’s a book that David David Nordfors and I published a few months ago called Disrupting Unemployment. And it’s about this difference between work which is related to tasks, which is what we typically think of as work. But unfortunately you can use robots to do a lot of tasks. We’re more interested in trying to capitalize on people’s capabilities, to find work that they can do that benefits from their skills and their special individual properties. And that’s a very different thing than just trying to focus on reducing the cost of tasks. So, thinking about work in a different sense than just production or something is an important thing.

We’ve already been through several situations where new technologies come along. The Industrial Revolution removed a large number of jobs that had been done by hand, replaced them with machines. But the machines had to be built, the machines had to be operated, the machines had to be maintained. And the same is true in this online environment. The machines that we use that enhance not only our muscle power but our brain power also have to be invented, maintained, and operated.

The problem may be, though, that for people whose jobs depended on their personal ability to do so something, those jobs may go away. And the question is what will they do? Some of them will succeed in being retrained. And this is in a sense—in this setting here at Elon—this is a very important observation, that education and work are going to be more entangled than they ever have been.

Historically, we went to school, we got a job (maybe get several jobs), and then we retired. That was it. And in theory, the education that we got at the beginning of our lives is supposed to serve us for the rest of our lives. Well, there are people being born today who will probably live to a hundred years old. They will almost certainly have multiple work that they can do. And they almost certainly will have to learn something during the course of their adult lives in order to continue doing useful work.

The implication of that is that this old term, continuous learning and continuous education, is real. It’s not just a slogan. And we have to figure out how to deliver that product. So, we’re sitting here on a campus whose purpose is to educate. I think that universities like this one and others are going to have to learn how to package their products up in order to deliver it when people need it at various times in their lives. It’s a very very different model than the one we’ve had in the past. But part of it has to do longevity. Part of it has to do with the rate of change of technology and the need to learn new things.

I can tell you at Google, where I’m surrounded by people who are a lot younger than I am, I have to learn new things all the time because they keep inventing new things to learn. And in some cases, I have to rethink what I thought I knew. So a typical scenario is somebody running up saying, “Why don’t we do X?” for some value of X. And I’ll think oh, we tried that twenty-five years ago and it didn’t work.

Then I have to remind myself there’s a reason it didn’t work twenty-five years ago, and it could be that reason is no longer valid. Computers are faster, they’re smaller, they use less power, they’re less costly. And so some of these crazy ideas turn out to be feasible. I’ve been forced to rethink a lot of things in the course of my almost eleven years at Google, as you will in the course of your lifetimes. So I am not despairing at all. Basically, I’m an optimist anyway. For the most part, I think we will figure out how to adapt to the need for new education as people find their jobs shifting from where it is today to where it will be in the future. So that’s my long answer to a short question.

Rainie: Your colleague, the Chief Economist at Google Hal Varian made a lot of headlines a couple of years ago, saying the sexiest job of the future was going to be statistician. So there are a lot of students in this audience who would like career advice from the great Vint Cerf. Are there particular directions that you would encourage students to orient their lives towards, if not specific jobs?

Cerf: Well, the particular statistics that Hal was referring to was almost certainly Bayesian mathematics, because everything we do depends on that little equation which in the 18th century was thought to be cute and useless. And of course almost everything we do now makes heavy use Bayesian analysis.

Well, let me think for a minute. Some young people come and say, “What should I do? What should I study?” And I tell them go into astrophysics. And the reason for this is very simple. A hundred years ago, we thought we knew everything there was to know about the universe and we just had to measure the constants more accurately to make all of our predictions work. Well, then Einstein comes along and blows up Newton. And then the quantum theory guys blow up Einstein. Then the string theory guys blow up the quantum theory guys. And then we discover that 95% of the universe is either dark matter or dark energy. We’ve given labels to these things, we don’t know what it is.

We know about 5% of the universe. So if you go into astrophysics, the chances of getting the Nobel Prize are extremely high because nobody knows anything. So anything you do is likely to win the Nobel Prize.

If you decide you don’t want to do astrophysics, what to do next? And I think that the hottest topics today have to do with the application of computing to other disciplines. I was in Lindau, Germany earlier this year, late June, meeting with thirty-five Nobel Prize-winning physicists and about 400 graduate students. And it was stunning to see how much the computer had become a tool for the physicists. In fact, the chemists, the Nobel Prize-winning chemists of a couple years ago were not wet chemists. They were modeling chemical interactions with high-performance computing in order to predict what the results were going to be. In every discipline, in biology, in medicine in general, we’re seeing heavy use of computers in order to model and analyze things. I hate to use this “big data” term, but in a sense that’s what’s going on, large quantities of data getting analyzed.

I happen to have a particular fondness for bioelectronics because my wife has two cochlear implants, and so she’s sort of like the Bionic Woman. Her hearing was restored after fifty years of deafness by an implant that goes into the cochlea, and the electrodes touch the auditory nerve and are fed by the implant. But signals come through her through her head through a magnetic connection from a speech processor that’s about the size of a mobile.

That thing is taking sound in, it does a Fourier transform to figure out which frequencies are present. It then decides which of the electrodes inside the cochlea it’s going to stimulate artificially. The brain interprets those signals as sound. So she hears more or less normally. Doesn’t hear music very well because it’s a very crude signaling system, but speech is great. So she uses the phone and listen to books on tape. She carries an FM transmitter with her, so if she were in the audience today I’d be wearing a little FM transmitter. She could hear me from 150 feet away.

So that’s bioelectronics, and it’s getting more and more elaborate. We’re seeing optical implants. We’re seeing spinal implants. So if you were going to go into a space that would have a huge positive impact for people with various disabilities, bioelectronics is not a bad place to be.

Studying pharmacology, for example. Inventing new drug treatments based on molecules that you invent as opposed to discover. All that stuff is there. It’s just… It’s a whole new world, waiting for people to explore.

Rainie: Let’s talk a little bit about the future of your baby, the Internet. Tomorrow night at midnight, the formal connection between the US government and the ICANN address-based system of the Internet will be disconnected. Potentially, depending on what American courts do. To whom are those functions being given, and should we be worried about that or take comfort from that?

Cerf: Well, I think you should take comfort. First of all, ICANN is the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers. Its task is primarily to manage the IP address space (those are the numeric addresses of the Internet) and the Domain Name System, which you use all the time when you’re using the World Wide Web. It was set up in 1998 at the request of the White House. This was under president Clinton. Ira Magaziner published a green paper proposing the creation of this organization. And eventually a white paper came out, and ICANN was established.

Why would they do that? Well, this business of managing the Domain Name System and the IP address allocation used to be done by one guy. He was a graduate student, and later a member of the scientific staff at USC Information Sciences Institute, Jon Postel. Way back in the late 1960s, he had this task. We called him the Numbers Czar. And he was just allocating address space for the predecessor to the Internet, the ARPANET. And later when the Internet was established, he did the same thing for the Internet.

ICANN’s job was basically to take the great pieces of the Internet address space and allocate them to what are called Regional Internet Registries, which in turn allocate IP address space to the Internet Service Providers. They also manage the root zone of the Domain Name System. So, .net, .com, .org, and all those other top-level domains exist in a file, and the file says if you’re looking for foo.com, here’s where all the .com names are, this IP address and that computer.

And the other thing they do is to maintain tables of parameters that are needed for the Internet protocols generated by the Internet Engineering Task Force, which does standards for the Internet, joined now by the World Wide Web Consortium. So, their job was essentially administrative. They didn’t tell people what to do with those addresses. They only made sure that IP addresses were allocated uniquely, so two people didn’t get the same address. The same is true for the domain names. They made sure that the domain names were allocated uniquely to a party that would manage the next level down.

The structure of governance of ICANN was multistakeholder from the beginning. The stakeholders included the the technical community, typically the IETF and the World Wide web consortium. Which, IETF is part of the Internet Society’s operation. So, they were the technical community. We had the business community. The private sector was another stakeholder group. A third one was the intellectual property group. A fourth one was the governments of the world were invited to participate in what was called the Governmental Advisory Committee. They didn’t make decisions but they influenced decisions because they fed advice to the board of ICANN.

So, there’s this multistakeholder process which has been refined over the last eighteen years and has been refined even more over the last two years in anticipation of this termination of the contract between the Department of Commerce—specifically the National Telecommunications and Information Agency—and ICANN.

What does that contract obligate ICANN to do? Well, it obligates it to manage the top-level domain space, manage the IP address space, manage the tables of parameters. The only thing that NTIA does is ask that ICANN tell them what changes they’re making to the root zone. Like, is .com pointing to this IP address or that one? This has nothing to do with the proliferation of domain names that you and I use. This is only the thing that points to the server that says this is where you find foo.com or bar.com and so on. have. It’s just what server is that and what’s its address. That’s all that’s in the root zone. And the only thing and NTIA ever did was say, “Please confirm to us that you used the agreed processes to process changes that were requested by the operators of the top-level domains.” That’s it.

And the only thing they could say was “no.” They couldn’t say “take this out.” They couldn’t say “put this in.” The only thing they could say is, “We don’t agree that you followed the right process to make this change.” They never, ever in the course of eighteen years said no.

So their function was to make sure that the process was followed. Well, now after two years of work designing a process in the absence of the NTIA component, the same sort of thing will happen. The same sort of mechanisms will happen. But the multistakeholder community will be the party responsible for assuring that the processes are properly followed. And there are a whole bunch of mechanisms that can be invoked if somebody thinks the process was not properly executed.

That’s it. You won’t see a change at all. Nothing will change. And so the people who are objecting to this misunderstand and misrepresent the role of the US government today in the operation of the Internet. And so from my point of view, this is essentially a NOOP. And it’s important to do it because there’s a lot of unhappiness around the world that the US has this special position which doesn’t actually amount to much. And so it’s symbolic. And for countries that feel like they should have an equal say, they find this special position offensive. When we remove that one special thing, everybody will be in the same boat. We’ll all be part of the multistakeholder community.

And so from my point of view it’s the right political thing to do, and it’s the right technical thing to do. So, that’s a long answer again to a short question, but that’s where things stand.

Unfortunately, on the stroke of midnight on September 30th, that transition may still not happen because four attorneys general in four states have sued ICANN, or I guess they’ve sued NTIA, to prohibit the transfer from happening. The Congress was going to put a bill or a rider on the continuing resolution— Senator Cruz in particular was in favor of that. And it failed. The Congress did not vote to incorporate that blockage into their continuing resolution. So in this I guess last-ditch effort four of these attorneys general have decided that they have standing to object to the transfer. In my view, they don’t have standing. There is no transfer of property or anything involved. But the judge in Texas will have to decide whether a restraining order is justified or not. So we won’t know, frankly, until some time at midnight whether or not the transition actually takes place.

Rainie: One of the last times you were in this community, you gave a wonderful talk in Raleigh, a part of which you outlined a dozen or more central questions about the impact of the Internet that were at that point not yet well-understood, and which researchers like the scholars in this room might be well-served to study. What would be at the top of your list now for things that we don’t know about the Internet and its impact that you would like to see resolved?

Cerf: Well, I don’t know whether these are resolvable, but they certainly deserve attention and study. So let me start out by observing that the more Internet is penetrant in our daily lives, the more we depend on it and the more its brittleness affects us. So when it doesn’t work, lots of bad things happen. This is true of almost all infrastructure. Nobody pays any attention to infrastructure until it doesn’t work right. So, when the electricity goes out, suddenly you worry about your ice cream melting. But during the normal course of events you don’t lie awake at three in the morning worried that the electricity is going to go out. Unless you happen to live in a place where it’s not reliable. Or the road system, for example. You take the roads for granted until they congest. Then you’re unhappy about that.

So if the Internet doesn’t work right and we’re depending on it, that’s a risk factor. Think for a minute about this avalanche of things, this “Internet of Things” which is coming. You can see little bits and pieces of it have been around for a while, like you know, Internet-enabled picture frames. But when you start designing your house around the notion of devices that have programs in them that communicate with each other and somehow use the Internet in order to interact with you remotely from your mobile. You don’t want your house to stop working just because the Internet isn’t accessible. That would not be a good design.

So I worry about the people who are inventing these various devices and have this assumption that the Internet will be there so they don’t have to worry about that part. Can you imagine going into your house with your mobile and about a hundred different apps, because somebody was so stupid as to make each light bulb a different app. And you’re trying to figure out how to turn the lights off and on. But the mobile isn’t working because its battery is dead, or you don’t have a good signal, or the WiFi is down. This is not sane. And so we really have to think hard about building robust systems that take advantage of the power of the network and the power of programmed devices, but at the same time protect us from the downside, which is when stuff doesn’t work right.

A third thing you mentioned already, and that’s malware, which is all over the place. Part of the reason that malware is a problem is not the underlying network itself, except for the fact that it transports the malware from one place to another. The reason malware is so damaging is that the operating systems that it attacks, the edge devices—your mobiles and laptops and servers—are the ones that are vulnerable. So it’s not the Net that’s vulnerable as much as it is the devices that use it for communication.

And here we have to put the blame on the people who write the software. And the finger points at me, too, because for years I made a living writing software. I admit I don’t make a living writing software anymore but I know carp about people who do. And in particular, the problem is that the software is not written without bugs. Frankly, for the last seventy years we’ve been trying to write software with no bugs, and we haven’t figured out how to do that.

So the result is we create software that has bugs. And we don’t notice it until too late. Somebody exploits the bug, something bad happens, then we try to fix the bug. And sometimes that means downloading new software into your laptop or your mobile or your toaster or something else. Then you get into this really interesting problem. Okay, can I develop software systems that will prevent me from writing mistakes in the code? And I have this… Imagine this artificially intelligent thing kinda sitting on my shoulder looking at the code that I’m writing. And it’s saying, “You you have a problem.”

“What do you mean I have a problem?”

It says, “Well, you have a buffer overflow at line 27.”

“Are you sure?”

“Yeah, let me show you.”

And it puts up a piece of the code. I need this little thing sitting on my shoulder to call my attention to mistakes I’ve made. And I don’t think it’s impossible to design something kind of like that, that is a piece of software that’s paying attention to the code I’m writing and is looking for mistakes. For example, here’s a variable in the code, and you read it, you use the value in that variable, except that nobody set it to anything. So you’re getting a random value. Well that could branch you off into cloud-cuckoo land.

We need to develop a much better ability to write software that is largely bug-free. We need also to make sure that if there are devices that we’re relying on that run with software, that they can be updated at need.

But now we get into another problem. How does the device, let’s say it’s your refrigerator, how does it know whether the software that’s being downloaded is coming from a legitimate source as opposed to some hacker somewhere? So now we get into this strong authentication question.

This just keeps going. I mean, you can a pull on this thread and you will discover a variety of different problem areas that need attention. Strong authentication implies good-quality crypto. Then you start worrying about quantum computing. And you wonder whether the current public-key cryptosystems are going to stand up against quantum computation.

In fact, just yesterday I was at Stanford University, and we had a discussion with about twenty-five different cryptographers about what comes after the quantum computer that breaks all the current codes that are relying on factoring as the work factory. And fortunately there’s good news. There are some mathematics that don’t rely on this particular property, which is how our current systems work.

So, I won’t go on and on. But there is just a fabulous array of conceptual problems that need attention, that have real-world consequences. And so I think that we all have an opportunity to tackle those if we have the interest in it.

Rainie: Pretty relatedly, there’s… Any number of your quite prominent colleagues have begun to express very deep concerns about the future of artificial intelligence and whether it becomes essentially a runaway or breakaway process. I don’t know that you’ve officially endorsed any of that. Could you tell us what to worry about, and where you think they might be overstepping logical concerns?

Cerf: Yeah. So, I’m going to talk a little bit about artificial intelligence later today. But first of all when I hear people whose opinions I usually respect, like Elon Musk for example, or Stephen Hawking, or Bill Gates, who are saying, “Ahhh! The artificial intelligence, the robots, are going to take over,” I’m a little surprised at this.

The theory that’s being put forward is roughly that once a computer learns how to do something that a person can do, then it will learn how to do it better and better and better until finally it’s better than anybody. And the things that get cited along those lines are for example winning Jeopardy!, or winning Go, which is a pretty impressive feat, as many of you may remember back in February. I think we played five Go games using the AlphaGo artificial intelligence system that the Google company DeepMind put together and trained. And it won four out of five games against an international Go player. And then of course there was the chess games that were played back around 1997 or so with Kasparov, and he was defeated as well.

The thing that you should appreciate is that the machines that do this have been very very narrowly programmed. This is not general-purpose intelligence. This is not understanding that if you let go of a glass it’ll shatter on the floor because there’s this thing called gravity. This is about very very narrow training to get a machine to do a particular thing. And often what it’s doing is either doing a rapid search through all possibilities faster than a human can, or it has been trained to build a neural network which after tens of millions of games has adjusted its parameters so it recognizes what to do. In some ways that’s what international grandmasters do, too. They see patterns in the chess game and they recognize those patterns and they know roughly what they should be doing about defending against the opponent’s moves.

This is not the same as the kind of intelligence that you have. You have the ability to induct from observation. You have the ability to reason, and you have the ability to predict consequences. Most computer programs don’t have anything close to that except in very narrow cases like the Bayesian analysis that I mentioned earlier.

So I don’t see the threat here. If there’s anything in the future for us, it’s using these tools to augment our own abilities. And I think this collaborative interaction, which you use every single day. When you do a Google search, when you use Google Translate, you are using artificial intelligence. But it’s under your control. And even with some of the more advanced things like Google Now and Google Assistant and so on, what’s going on is the machine trying to capture information that it things will be useful to you and then provide it to you in a timely way.

But that’s not the same as something taking over your life. It’s just providing you with advice. So I don’t think you should worry as much about that as you should worry about bugs in the software that cause all kinds of troubles. Or mistakes that people make.

Rainie: Let’s look backwards for a little bit at your baby and how it’s been used, all of the applications and different layers of the Internet. I wonder if you could just do a little quick march about your own discoveries of the way that people have used the Internet. Your first experiences on the Web, your first emails, your first Skype calls, your first use of apps. Walk through the sort of Vint Cerf hall of delights as you’ve watched your baby grow up.

Cerf: Except that you know, I didn’t write down… So, first of all electronic mail was invented before the Internet. It came as part of the ARPANET experiment, in 1971. It was an engineer named Ray Tomlinson who passed away a couple of months ago who realized that you could move files from one computer to another on the ARPANET. We designed it to do that. He said well, why—email was something that people shared on common time-sharing machines. If you had an account, and somebody else had an account on the same machine, you could send files back and forth.

But he had the idea that he could use the ARPANET to send files from one machine to another. And so he thought, “Well, if I could just leave this file in a directory that the recipient could find, then I could communicate.” So he wrote a little program that took a file from one machine, sent it to another. Then he said, “Okay, how do I figure out— I have to say which machine it’s supposed to go to, and then I have to say which directory it’s supposed to end up in.” Well, the directories were associated with users’ names, with their login names.

So he decided, “Well, okay. I write that somehow. How do I separate the user name from the computer name?” And the only character he could find on the keyboard which wasn’t already used by some other operating system was the @-sign, and somehow that made sense—user@host, right. So that’s why you have user@host as your email addresses.

So he invents that in 1971. We all go nuts because suddenly we realized that we have a computer-mediated communication system. Then we realized that means that you don’t have to be concurrently interacting with each other like you do on a phone call. That means you that could talk to each other even if you were in different time zones. And so we got all excited about that, realizing that meant we could manage projects over multiple time zones more easily than we had before.

But what was surprising to me is that that wasn’t the most interesting use of email. Within a few weeks of email’s arrival, which we all took up and and made use of, there were two mailing list created. The first one was called Sci-fi Lovers [SF-Lovers] because we were all engineers, we all read science fiction, and we wanted to argue over who was the best author and what were the best stories. So that was a mailing list which had social consequences. The next one that comes along is Yum-Yum. It’s a restaurant review thing that Stanford put together, which eventually expanded over a larger territory than Palo Alto.

But the point is that the two mailing lists that got started were clearly social networks. So right away you could see that this network was becoming a socially interesting phenomenon. And that’s still in the ARPANET days. By the time the Internet comes along, of course, now multiple networks can happen, it’s spreading more broadly, more and more people can participate.

When the World Wide Web shows up, it’s a very interesting observation. Tim started that work, Tim Berners-Lee—sorry, Sir Tim Berners-Lee—in 1989 while he was at CERN. And he released his first version of the World Wide Web around December of 1991. Nobody noticed.

Then Marc Andreessen and Eric Bina of the National Center for Supercomputer Applications in Champaign-Urbana at the University of Illinois do the Mosaic browser, which is a graphical browser. Suddenly the Internet looked like a magazine with formatted text and imagery and eventually streaming audio and video.

Everybody goes nuts when they see that, including a guy named Jim Clark, who grabs Eric and Marc Andreessen, drags them out to the West Coast and starts Netscape Communications, which goes public in 1995, and the stock goes through the roof. It starts the Dot Boom. But what impressed me was not the Dot Boom. What impressed me was the avalanche of content that people poured into the net once it was easy to create that content and share it.

And the thing that was the most amazing is not just the quantity, it’s the fact that people wanted to share what they knew. They weren’t asking for remuneration, they just wanted the satisfaction of discovering that something they knew was helpful to somebody else. And that phenomenon persists today. And so that probably is the biggest surprise, is how much we want to share what we know. And of course the social networks that we see today are just evidence of this increasing amount of desire to share what we know. So that’s probably— My introduction to the social impact of the Internet comes twenty years ago plus, twenty-five years ago, as the World Wide Web starts to show up.

Rainie: Unlike a lot of others who were involved in the creation of the Internet, you haven’t yet written a book.

Cerf: That’s true.

Rainie: And I wonder if there is anything holding you back, or if there are things that you would say in a book if you ever had the opportunity. Maybe a book is itself isn’t the scholarly container to know what you know, and that you are thinking different thoughts about pulling it all together. But I’d be interested in hearing you talk about that.

Cerf: There are actually five books that I would like to write. One’s a book of poetry, another one is… Well, let me get them in the right order.

The first one I want to write is my wife’s biography, because that’s the most interesting story, much more interesting than mine. I mean, this transformation from being deaf to hearing after fifty years is just unbelievable. There are all kinds of great stories to tell. So that’s first—

Rainie: You have to tell the title story of that book.

Cerf: When Sigrid got her cochlear implant in 1996, the first thing that she would say when we took the dog out for a walk was, “I heard that!” Like the birds were tweeting, and things like that. And so the book, I was going to title it I Heard That!. And in fact my good friend Gene Gabbard who’s sitting here in the front row— She was here visiting in North Carolina and borrowed a mobile phone to see whether or not she could use the mobile phone to call someone, and it worked. She took his car and the mobile phone, drove around the corner and called Gene, and it worked. So this was spectacular. It’s been one spectacular thing after another

So the thing that I thought I would do is call it I Heard That, but then one day we were going to Washington on the Metro, and there was a person on a mobile phone behind her. She has this little patch cord with a microphone on the end of it that goes into the auxiliary input of her speech processor. So she plugs it in, and she tosses the microphone over her back so she can snoop on the guy who’s talking on the phone. And I was kind of embarrassed about that. I kind of moved away. And later I told her, “Okay, I am going to write your biography, but it’s not going to be called I Heard That, it’s going to be called Snoopy.”

What was really amusing, though, was after her first implant was done, they turned it on. I wasn’t there. At the time I was in a board meeting. But she called me twenty minutes after they got the speech processor organized, and we had a conversation over the phone for the first time, after being married for thirty years. That was amazing.

By the time I got home, I discovered I had a fifty-year-old teenager at home. I couldn’t get her off the phone. Anybody would call— I was Senior VP at MCI at the time, right. So AT&T would call to try to get her to switch to AT&T. So she’d call them, say, “Oh, hello. Where are you? Oh, you’re in Bangalore. Well, tell me about that.” So half an hour would go by and this poor person on the other end of the phone would say, “Well, you’re going to switch now, aren’t you?” She said, “No, my husband works at MCI, but thanks for calling.”

So then she called the library and said she wanted to to get recorded books for the blind, because she wanted to listen to words that she hadn’t heard. She didn’t say that part. She just called the library and said I’d like to sign up for recorded books for the blind. They said, “Oh fine, no problem; name, address, phone number. Now, you’re blind, aren’t you?” And she said, “No, I’m deaf.” And there’s this long pause, and they’re trying to figure out how’s that going to work? So she listened to five hundred books on tape, or recorded books. Now she can tell accents and mistaken pronunciation. Very impressive.

So anyway she has this great story, so I want to do that biography. I should either try to do a definitive history of the network, which would be very hard because there’s a lot of it now. I might be able to go from ’73 to ’93 largely on my own with a lot of material that I’ve accumulated. But to go another twenty years would really be tough.

Or I’ll just do a memoir, you know, because I know where all the skeletons are anyway. So I might do that. And then I have a few others I’d like to write. The trouble is that travel seems to get in the way, and I travel about 80% of my time. So that’s my excuse so far. But if people like Lee keep beating up on me and saying, “You’re going to forget all this stuff. You need to write it down,” I will be listening.

Rainie: Well, I add my vote to the “yes” crowd that would like to hear from you in that way. I’d like to invite anyone in the audience who has a question for Dr. Cerf to come to the microphones and ask it. As people are doing that, I’m going to go back to a sort of geeky part of the technology conversation. Have you used Bitcoin?

Cerf: No, I haven’t used it. [crosstalk] I run away from it.

Rainie: But part of the hype cycle. Oh, okay. Because one of the things now that is capturing the imagination of the technology community in a large way—it’s probably cresting at the top of the hype cycle—is blockchain, [crosstalk] the underlying ledger system.

Cerf: But let us now make an important—

Rainie: He’s going to correct me folks.

Cerf: Yeah, no no no no, no no. Blockchain is a correct statement. I want to distinguish, however, between Bitcoin and blockchain. Blockchain is the underlying mechanism, Bitcoin puts on top of that, slathers on top of that, a whole bunch of other stuff, including this bitcoin mining thing which has led to a kind of missile/anti-missile you know, build a bigger computer to do the mining and win the race to win the bitcoins. So that first of all is not a sustainable—

Rainie: My real question was about blockchain.

Cerf: Oh, okay.

Rainie: There are a lot of people who have very high hopes for its capacity to to fix some of the problems of the Internet, and…

Cerf: Well… I don’t think—

Rainie: The trust and authentication—

Cerf: Blockchain is not fixing a problem in the Internet. What blockchain is doing is allowing you to build what’s called a distributed ledger. And that means that multiple parties can store information about for example a transaction. And because of the way the transactions are constituted, you can’t alter the transaction without it being visible. So this is an integrity issue more than anything else.

The problem with the blockchain is that in one form, none of the parties are known to each other. And so it’s anonymous. And I don’t believe that the anonymity is necessarily very valuable. I would much rather know who is maintaining the blockchain and have some confidence in the institution that’s doing that. So those are two different kinds of uses of blockchain.

But the thing I want to warn against is that the fundamental blockchain mechanisms, the cryptographic mechanisms, may be coded exactly right. And they probably are for the most part. But there is a big surrounding chunk of software that has to be written in order to make use of the blockchain technology itself. And if that software has bugs, then you wind up losing the value of the blockchain. And the case in point is Bitcoin, where companies like Mt. Gox lost $400 million worth of bitcoins because somebody penetrated the software. Not the blockchain part of it, but the rest of it.

And so this gets back to my earlier peroration about the problem of bugs in software. So we’re back to blockchain may be wonderful, but we had better learn how to write the software that surrounds it more reliably or it will fail to be as useful as people would like it to be.

Rainie: Thank you.

Cerf: Shall we get some questions?

Rainie: Yeah.

Vint Cerf: Now, I’m going to test something here. Don’t panic, I may jump up and walk to the edge to the stage in order to lip read if necessary, because I’m hearing impaired. But go ahead and have a shot.

Audience 1: So my question is, looks like from what we’re talking about, AI and the advances in Internet, it’s really restructuring all of society and kind of changing the way humanity thinks about what its role is. So, being one of the most important people in founding the Internet, what do you think humanity’s new role is, or what are some of the new roles that humanity needs to consider as we go through all these massive structural changes?

Cerf: So let me summarize, and you tell me if I got this. The short story is is artificial intelligence going to change our society in ways that we don’t like and what should we do about it?

Audience 1: No, more so what do you think—

Cerf: Alright, so that’s why I’m going to get up and— Well, the reason is that there’s this little speaker here. Go ahead.

Audience 1: So what do you think our goals should be as we go about drastically changing all of humanity with the Internet?

Cerf: All of the…?

Lee Rainie: Humanity.

Audience 1: Internet, AI, VR, AR…

Cerf: Well, look. I think there is an ethical issue here. And the ethical issue has to do with being able to if not predict at least try to analyze the consequences of the technology that gets fielded. And so I’m very concerned about the software side of things, which is why I’ve been harping on it this morning, or this afternoon I guess. That’s my biggest worry, is that people will not understand that they are creating an environment which may be brittle and may be exploited, and not pay attention to that or not even care about that. And I don’t consider that to be proper either individually and professionally, or corporately. So that’s my big worry, is this proliferation of software which fails to take into account what happens when it doesn’t work right. And that’s my biggest worry.

And I don’t have a lot of good answers for how to prevent that from happening, other than to put some pressure on people who produce that software. Eventually I think there will come a time when programmers will not be able to get away with “it’s just a bug.” It will be, “That was your software, you’re responsible for it.” Now, what the consequences are I don’t know. We’ll have to see what measures can be taken. But I think we have to face that.

Let me go over here and I’ll alternate back and forth. So that means the guys that’re over here, if you want to get there faster might run around the door here. You’ll reduce the average—no, that’s alright, go ahead.

Audience 2: Good afternoon, Dr. Cerf. My name’s Kanon[sp?], and at the beginning you mentioned trying to achieve Internet access for everyone, of the whole planet. So, do you think the responsibility of getting Internet access to everyone lies more on the public sector, so getting the governments to try to provide WiFi or just Internet access in general? Or the private sector, because I know Mark Zuckerberg is very famously going after it very aggressively and trying to get Internet access in Africa and places like that.

Cerf: So, the honest answer is that this is an opportunity for all kinds of different parties to engage. And I’m very concerned, for example, that the American Indian population doesn’t have access to the Internet on the reservations here in the United States. It’s just nonexistent, for the most part. And we’ve failed miserably to do anything about that and that’s just wrong.

But the same argument could be made in other parts of the world. Now, there are technological responses that we can make, and there are policy responses we can make. On the technology side, Google is doing some fairly crazy things. We have this Loon project. These are balloons at 60,000 feet. They circle the Earth at that altitude. We steer them based on the jet stream and altitude, so that depending on which way the jet stream is blowing we’re able to guide the balloons over their next site to deliver Internet service by WiFi or LTE.

So that’s one kind of thing. Others are looking at the possibility of putting in low-flying satellites, for example the O3b system is a dozen satellites in equatorial orbit at 8,000 kilometers. Which means it’s a fifty millisecond up and down, which is more like a continental delay than the usual synchronous satellite delay. Again, covering 40 degrees North and South. So there are a bunch of technological things that we can do and are being pursued as real businesses in the private sector.

But, it also can happen that governments can choose policies where, like in the case of Australia there was an interest in building a national broadband network. That was a government investment in infrastructure, just like the roads, on top of which the private sector could then build. We have some experience with this at Google. In Kampala, Uganda we built in a gigabit fiber network which we operate as a wholesale facility. We sell to retail providers, and they resell to the public. And so it was an investment in infrastructure which is intended to help jumpstart the use of Internet in that part of the world.

So I can see combinations of government policy that encourages investment, policy that encourages competition, policy that encourages companies to invest. The mobile has helped very greatly in getting access to Internet out there. Because before the mobiles, you had to pull wires. WiFi didn’t reach far enough. But now we have mobiles and a lot of people are using smartphones as their first way of getting access to the Internet. And as time goes on that may be the primary initial experience that people have, which is why a lot of companies like Google and others are trying to make mobile as useful as possible.

So, my sense right now is that there are wide-open opportunities to create more access to the Internet all around the world. And depending on where you, what physical conditions are, and what the policies are, you might use choose multiple different paths to get there. So, I spend a lot of my time around the world talking to governments about policies that would promote that. And anybody else who wants to help, you know, you should do that.

Audience 2: Thank you.

Cerf: Okay I’m going to switch over here now.

Audience 3: Good afternoon. My name’s Ben. My question is, based off what you’ve already spoken about and other experiences, what was the hardest challenge to overcome in your professional career?

Cerf: The hardest challenge? [long pause] Besides raising two sons. Which my wife gets most of the credit for. You know, the most interesting and hardest problem is getting people to want to do what you want to do. And so I teach my engineers that you have to learn how to sell your ideas if you want to do something big. And so I spent a significant amount of my time convincing a whole lot of other people they wanted to make the Internet happen. And that’s been fairly successful. And part of the reason is that a lot of people decided they wanted this to happen, they wanted to participate in it.

And so some of the engineers, for example, think that marketing and sales is this thing over here which is not worth their attention at all. I have to remind them that if the sales teams don’t succeed they won’t get paid. And their attention suddenly goes up again. Selling your ideas to other people is probably one of the most valuable skills you can have, and it’s certainly the biggest challenge for me.

The second biggest challenge in the case of the Internet turned out to be a competition between the TCP/IP protocols and the OSI (Open Systems Interconnection) protocols. That competition went on from 1978 to 1993. And although I wasn’t the only one fighting this battle, it was governments that had to be persuaded that the international standards were not as functional and not as ready for implementation as the ones that the American Defense Department had sponsored. And you can imagine the political tension here. “Why would we want to adopt a US defense department protocol when we have our own standards-making activity in the International Telecommunications Union and the International Standards Organization?”

So that battle took a long time and eventually was overcome by simple sheer force. The protocols of the Internet were implemented and propagated everywhere. They were freely available. Bob Kahn and I gave that away on purpose. And so it was a really powerful tool. No barriers to adoption. So if you want your ideas to penetrate, maybe you should think about giving them away instead of patenting and controlling them. So that’s one answer, anyway.

Audience 3: Thank you.

Audience 4: Hi. My question is also about kind of getting Internet to the rest of the world. And it’s a little multifaceted, I guess. What do you think the best way to get developing countries online would be, and what do you think the impacts of— I guess now statistically 100% of developing countries somewhere have access to the Internet, but kind of the proliferation of that access to more people. Like, what are the impacts of that? And do you think there’s a reason (You said you’re an optimist; I guess maybe I’m a pessimist.) that these people aren’t online right now. It’s been eighteen years, and it seems like it’s going slowly, or like you’re saying, American Indians don’t have access. It seems like they live in the country that the Internet was created in, so why shouldn’t they have the same kind of rights as we do?

Cerf: So, let me let me come at this by telling you a story about the refugee camps. And this present situation especially with ISIS, and the situation in the Middle East has caused an awful lot of refugees to migrate away from all the risk. The first thing they ask for is not food, shelter, or clothing, or anything. They ask for Internet access. And the reason they do that is that’s how they get information. That’s how they can contact their families and let them know where they are and that they’re okay.

So there is no doubt in my mind that Internet access is important in all countries of the world regardless of their economic situation. And you’ll hear some people say, “How can you possibly waste money on getting Internet infrastructure in place when they need clean water and food and housing and so on and medical care?” All of which is true. But the Internet, to the degree that it is a useful tool for causing actions to happen, for getting information to find out what to do, what’s available, where is it, how do I get, it’s a really powerful tool.

So I’m big fan of getting everybody online. I’m disappointed to tell you that in the United States, according to Lee’s work— I hope you don’t mind my doing it this way, Lee. I can hear better this way.

Rainie: It’s awesome.

Cerf: I don’t mean to just turn my back on you.

Rainie: No.

Cerf: You could stand here, if you want to.

Sorry about that. I just was conscious of the fact that I’m showing my back to Lee.

His work shows that in the US, only about 80% of the population is online and the other 20% doesn’t want to. And there are a number of reasons that are given for that. Some of them are economic, some of them are you know, “I hate social media and I don’t want to have anything to do with the Internet.”

So that’s disappointing and a little scary, because it might mean the same statistic would show up elsewhere in the world. But I do believe that we have an obligation— Maybe you don’t, but I feel an obligation to do everything I can to make sure people can have the opportunity. They can decide whether they want to get on or not. If it isn’t available, and isn’t acceptable, and it isn’t affordable, they can’t make that decision.

I’ve been involved in something called The People Centered Internet for the last year or so. The whole idea here is to make use of the Internet in order to provide information to people that they will find useful, that will improve their lives. Quality information about healthcare being an obvious example. And so I still believe that having access to information on the network is one of its greatest values, and this theme of sharing what you know is still there and still powerful.

However, there is one other problem that you have to deal with. There’s a lot of misinformation and disinformation on the Internet. The Internet has no idea what it’s carrying, just like a postcard doesn’t know what you wrote on it. And so we inherit an obligation to think critically about what we’re seeing and hearing on the network. Because there are people out of ignorance who will put wrong information on the net. Some people put bad information on purposefully. Sometimes they do it in order to get you to do something like go to a web site and give away your password.

So we are now obligated to think more carefully about the information we both give and receive in the net. We’re obligated to teach our kids that. Because they’re going to be faced with information sources not just on the Internet but everywhere. Movies, television, radio, newspapers, magazines, and so on. Their friends. And so still thinking critically turns out to be really important. So one thing we should do as we try to bring this gift to the developing world is to make sure they also understand that critical thinking is part of the deal. Okay.

Audience 4: Thank you.

Rainie: We’ve probably got time for about two more questions, I’m afraid to say, because we’re off to other things and you have to go to classes.

Audience 5: So, I was wondering, when you first started working on this project what sort of things were you imagining, envisioning back then that are here in the Internet now, and what things are here in the Internet that surprise you?

Cerf: So, this is question #102, which in short form is, “What were you thinking?” So, first of all you should understand that this project arose out of a Defense Department interest in using computers in command and control. The theory was if you could put computers to work managing your resources, you might be able to overcome a larger force by managing your resources better than the opposition. And that meant putting computers in airplanes, ships at sea, mobile vehicles, as well as fixed installations. That’s what led to the basic Internet design, multiple different networks, radio, satellite, fixed-wire line, and so on, all having to interwork in some uniform way. So that’s what drove us towards the Internet protocol.

The second thing is that we knew the military had to operate on a global scale, because we didn’t know where they might have to go next. So we designed it to be non-national in character. So the address space does not have anything in it that says “this is a US thing and this is a French thing.” At a higher level, you see then in the domain name space, you see .us, .fr, .ee, but you also .com, .net, and .org, which are global and not national. So we were driven by necessity into the architecture that you see today.

The command and control part also pushed us towards testing packetized voice and packetized video. So, in the 1970s, we were doing packetized voice and packetized video. Not very much of it because the data rates that were available were fairly low. But today when you do streaming video, and when you do a Skype call, you’re exercising mechanisms that we were experimenting with and recognized the possibility of forty years ago.

Now, I won’t tell you that we envisioned everything that’s happened. I’d like to say that, but of course we didn’t. But we actually had had quite a bit of experience with the ARPANET and the social element that around arose out of the email. And so we had some fairly clear sense of some of what would happen. When the World Wide Web showed up, that was much more shocking in some sense because of the graphical interface, the colorful nature, and the composition of voice and video and text format and everything else.

The advertising thing was not entirely obvious. There were a number of people who tried banner ads and failed. Until Google came along and figured out that the search engine bound with the advertising was a good combination. The search engines themselves weren’t necessary until the avalanche of content showed up on the net and people couldn’t find anything. So the search engines were the tool for for doing that.

What you should recognize is the Internet has evolved in steps, where a new capability is created when it’s needed. This is also true institutionally. So, we invented the Internet Society in order to support the Internet Engineering Task Force when the government said they don’t want to pay for that anymore. The ICANN got created when the USCISI said, “We’re in a space where we’re afraid we’re going to get sued,” and Jon Postel didn’t want to get stuck with that, and so he went off to take actions which triggered the creation of ICANN. The Internet Governance Forum got created out of a big debate about how we should do governance of the Internet.

And so one of the nicest things about the Internet story is its ability to adapt and to create new technology and new institutions, at need. And it’s continuing to do that today. And so from my point of view it’s been fortunate that you didn’t have to predict everything. That the system was so flexible that it allowed you to invent on the fly. And it’s still true today, and I’m hoping some of you will wind up inventing some stuff that nobody thought of, and maybe that will turn out to be a big, impactful effect. And that might be you.

Audience 6: Hello, Dr. Cerf. Thanks for coming. You touched on this theme a bit as you went through your talk, but I just wanted to hear some more of your thoughts on it. What do you think about the state of optimism in 2016? It’s been said that it’s unpopular now—

Cerf: Wait wait wait. I’m missing part of this. So we’re going to do this the easy way. [steps down from stage] I’m sorry about this for the guys on the camera. The state of…?

Audience 6: The state of optimism in 2016.

Cerf: Optimism, okay. And should we be optimistic or pessimistic about the net?

Audience 6: And also how other people have… I feel like there’s this idea that cynicism is the truth a a lot more more. And you said you’re an optimist. What do you feel we can gain from optimism, and what do you think about the fact that cynicism is the in thing now?

Cerf: Okay. So I’m still not sure I got all of this. You want to know why I think that the Internet is something I should be optimistic about as opposed to pessimistic about? Or—

Audience 6: For the most part. Just in the world in general, like how do you—

Cerf: Well, okay. So, look. We have to be realistic about this. The Internet is a place where bad things can happen. It’s a platform. It’s an infrastructure. Look, let’s take cars and roads. People get into their cars and they drink and they drive and they run into things. So they run into each other, they destroy property. And at this point, we don’t abandon all cars and shut down the roads because it’s too valuable, and I would argue the Internet is like that. It’s a valuable infrastructure.

So what do we do about bad behavior which would drive us into the holy cow, this is a pessimistic environment? The answer is we adopt policies and practices that say to people there’s some things on the net which are not acceptable. And if we catch you, there will be consequences.

So, I have three solutions for the bad part of the net, the things that happen that we don’t like. First one is to find ways to prevent the bad thing from happening, technically. So we defend against denial of service attacks. We try to write software that doesn’t have exploitable bugs. There are a whole series of technical things we can do. We use cryptography in order to protect people’s privacy and confidentiality.

But then, if we can’t stop all the bad things from happening, then we say okay, “If we catch you doing this thing, we consider that unacceptable and there will be consequences.” That’s sort of post hoc enforcement. And we do this in law enforcement all the time. We tell people, “Here are the rules. We know we’re not going to stop everybody from doing these bad things. But if we catch you, there will be consequences.”

Then there’s a third thing you can do, and it’s going to sound weak. And that’s to tell people, “Don’t do that, it’s wrong.” Now, that sounds like sort of…it’s as weak as gravity, because gravity is the weakest force in the universe. Except, you notice that when there’s enough mass, gravity is really powerful? Social memes and accepted behavior patterns are powerful. And so if we tell people, “Don’t do that because it’s wrong,” and if enough people say it’s wrong, then you will have an impact on people’s behavior. So like I say, I am optimistic about the human race, although there are times occasionally when I feel less optimistic. But on the whole, I think we’re going to be okay.

Alright let’s get this one over here.

Rainie: I think we will have to make this the last question.

Cerf: Oh, really? This poor guy was waiting.

Rainie: Okay.

Audience 7: I feel bad.

Cerf: It’s not his fault that I have long answers.

Audience 7: First off, I just want to say that I’m quite a big fan of your work. I don’t know if you get that all the time. But I feel like a lot of the questions have been “what do you think the impact is on the Internet on everybody else.” What is your favorite use of the Internet?

Cerf: Honestly, short answer, Google. And it’s not because I work there. I use it all the time to find stuff on the net. I can’t even sit down to write a paper without using Google. Once when the power went out I tried to write a paper longhand and I couldn’t do it because I got three sentences in and I needed to look something up, and the net wasn’t available. And I’m just sitting here fibrillating. So the honest answer is being able to find stuff on the net, is what really turns me on about its availability. So I use it all the time.

Audience 7: Thank you.

Cerf: Last question.

Audience 8: Well first off, thank you for actually taking my question. You kind of touched on it in the last answer you gave, like the bad actors that are on the Internet and sort of trying to stop bad actions. I wanted to talk about the sort of disconnect between what you do online and the social consequences that you may or may not face offline, and sort of what we can do to stop these bad actors in terms of government regulation, whether it be policies to say you can or can’t do certain things on the Internet, without infringing our right to freedom of speech. Because one of the things that sets the Internet apart from other mass mediums is that there is the aspect of interaction, and that’s what makes it unique. So, what do you think?

Cerf: So, there are several things here. You packaged up what turns out to be a fairly big issue. The first thing I would observe is that those of you who drive in your cars, probably especially if you’re alone, feel protected by the windshield so that you can say things that you would never say in public to anyone, especially about the person that just cut in front of you. Or the light’s green and it’s just sitting there, and you’re saying, “You [mumbles]…” So, we feel a little protected by our laptops and desktops and mobile screens, like they can’t reach us through there. And so there’s some behavior which is a consequence of that.

The second thing is that there are some people who imagine that they can say and do anything they want to because they are “anonymous” and nobody will know. I think that’s turning out to be less and less true. That discovery of the origins of things is becoming more common than it used to be. Part of it is because we have better tools for doing that. But there are people who think that because they can’t see the consequences directly, that therefore there aren’t any.

We had a huge debate at Yale a couple years ago exactly on this topic. We were talking about multiuser games on the net, and the sorts of things that happened there. And some people said it didn’t matter if you were really nasty and brutish, because it was just a game. And yet there were people on the other side of those avatars, and there were real consequences to that. And so we were arguing that. And the team that took the position that there are real consequences won that debate on the grounds that there really are consequence. And so we’re back to recognizing the impact of what you do. And maybe we have to make that more visible somehow, so people are conscious of that. But we’re back to sort of social engineering, where people need to understand that when they’re texting, when they’re playing the multiuser games, that there are human beings on the other side and that you have an obligation as another human being to recognize that.

This is not always an easy lesson to teach, and we’re back to sort of values again, and trying to help people recognize that the values they experience in face-to-face interaction should apply in this online world as well. And that probably takes a little bit of training for people to recognize, because the consequences are a little different than having you get very angry and punch me in the nose for having said something because we’re only two feet apart. Well…six feet. (I’m and engineer, I have to get this right.)

So I think we have to have a job ahead of us to help people recognize that there is really no difference between the interactions we have through this medium and the interactions that we have face-to-face.

Cerf: I guess that’s all time we’ve got, Lee.

Rainie: So, thank you. I have two final things to say. Everyone who is here today can and should either pick up the phone or broadcast in some way that you were in the presence of greatness. Call a friend, call your parents, call somebody, or post to somebody who’s important in your life saying you were in the presence of greatness. And no one should ever be in the presence of this man without beginning and ending the conversation by saying thank you for the wonderful thing that gave us. So, thank you very much.

Further Reference

Overview post about the award ceremony.