Joan Donovan: Hey, everybody. We are at the top of the hour here, and so it’s really exciting to be able to talk with this community, although I really…you know, miss the yellow house here. It always is such an exciting experience to be able to you know, hang out, shoot the shit and like, get into these issues in a real way. I feel quite a bit of distance from my communities of researchers, and because of the pandemic. But luckily I’ve been able to work with an incredible team at Shorenstein with a little bit of crossover at Berkman in order to sort of sustain my intellectual life.

And one of the things that we’ve been spending I would say the last two years on—my life, but different folks have been engaged with it for different amounts of time—is this media manipulation casebook. And what we’re really trying to do is present a theory/methods package for studying media manipulation and disinformation campaigns. And over the last several years I’ve been really engaged in this specific topic because ultimately I think the question of media manipulation and disinformation for me really is about do we have a right to the truth. Do we have a right to accurate information. And as we’ve watched the last…probably two decades of technology develop we’ve seen the foreclosure of some of our other trusted institutions where we’ve seen you know, the drying up of local journalism; we’ve seen universities come to rely on Google services for most of their infrastructure; we’ve started to see social media kind of take hold of the public imagination. And none of these things are really thinking a lot… None of these things are really designed, I should say, to deal with what we’re going through in this moment, which is profound isolation, coupled with immense, and warranted, paranoia about our political system, and economic collapse. And you know, I spend a lot of time in my room, just like the rest of you, trying to figure out some of these big questions.

And so today I really want to talk about, well what is the price that we’re really paying for unchecked misinformation; about the way in which our media ecosystem, to use a turn of phrase from Berkman Klein’s illustrious history, what are we doing here with this media ecosystem in the midst of a pandemic, knowing that the cost is very high if people get medical misinformation before they get access to timely, local, relevant, and accurate information.

I’m gonna share my screen; got some really great graphics that we developed for the Media Manipulation Casebook at mediamanipulation.org. And these were developed by Jebb Riley, which is a amazing illustrator, and he’s been helping with our team over the past few months sort of get our stuff together.

So this is who I am. I am right now the Research Director and the Director of the Technology and Social Change Project at the Shorenstein Center. But apparently the Shorenstein Center is just like, my house at this point. It’s really hard to think about what a return to the university’s going to feel like, given the fact I’ve spent several months working from home. But today I’m going to present on The True Costs of Misinformation: Producing Moral and Technical Order in a Time of Pandemonium. And I choose that word really intentionally and I’ll tell you why.

But first a few key definitions. So what am I talkin’ about when we’re talkin’ about media manipulation and disinformation online? We’re talking about basic Comms 101. Media is an artifact of communication. So you know, notes and books and you know, any kind of thing…memes, what have you, artifacts, things that are the leave-behinds of public conversation for the most part is what we study. But when I talk about news or news outlets I will talk about news and news outlets using that terminology. But when I say media, I’m referring in a way to this kind ephemera.

Manipulation. My team has debated quite a bit, and if Gabby Lim is listening, she’s been at the forefront of us trying to get our definitions in order. Manipulation to us is “to change by artful or unfair means so as to serve one’s purpose.” And we leave the term “artful” in there because as I was doing a history of media manipulation on the Web, I was drawn into the work of The Yes Men, who are media activists who really you know, figured out early on that who can own a domain? And apparently anybody can. Because they bought the domain associated with the WTO, they bought a domain associated with George Bush. And instead of really lambasting these groups, what they did is they impersonated them in order to draw in other folks. And there’s been several documentaries made about The Yes Men and their media manipulation hoaxes. But for them, the point isn’t to keep the hoax going. The point is to reveal something about the nature of power. And so manipulation in that case, for me, is a sort of an artful hack. And we can talk a bit about white hat hacking and gray hacking if time allows.

But when we talk about something as disinformation we actually try to apply a very strict set of criteria. And we define it as “the creation and distribution of intentionally false information for political ends.” And intentionality…you know, for anybody on the line here that is a lawyer you are just cringing right now. I can kinda feel it through the webinar. And don’t worry, I’m not going to talk about the freeze peach that just you know, sets your hair on fire. But intention is hard. I’m not gonna lie. Who can know a man’s heart, right?

But the issue here about intentionality, usually with disinformation campaigns if they are to set off a cascade of misinformation, manipulating algorithms in particular, generally these groups have to recruit from more open spaces online. And so we’ve seen you know, different for…you know, Reddit groups for instance be repurposed to talk about the intention of what it means to spread disinformation and how to get one over on certain journalists. And so we are able to discover intention when we can discover where a media manipulation campaign is being planned. But it’s a really hard thing to assess without direct evidence. But nevertheless when we talk about disinformation it’s because we have some direct evidence that points us to the intention of the campaign.

So, I want to recognize that we’re in a moment of extreme emotional deprivation…you know, social isolation. And this word the “pandemic” is something I was really drawn to thinking about it in its etymology, of thinking about “of all the people, public, common, (of disease) widespread. So “pan” and “demos” together, thinking about those kind of ills that spread in these kinds of situations that are in some respects completely unpredictable and hopefully at least for my lifetime, once in a lifetime.

But I prefer to call this moment “pandemonium.” And I’ll tell you why. So “pan” meaning all but also… I mean “demos” meaning all, but “pan” meaning evil spirit, evil, divine power, inferior divine being. And the reason why pandemonium for me is a better descriptor of this moment is I think back to right at the beginning, when most people were like, “Okay, we can handle this. We’ll get through this. This isn’t going to be a problem. We’re just gonna— You know what, everybody go home from school. We’re just gonna get on Zoom.”

And it created quite a chaotic environment. When we were thinking about how do we write about the phenomenon of Zoom bombing, my coauthors Brian Friedberg and Gabrielle Lim, we were talking a lot about well where does this opportunity arise from where you have a bunch of people adopting a brand-new technology very quickly, you have institutions buying into it at massive volume, and then you have students who are not really bought in to wanting to be on Zoom all day.

And so, some of the early instances of Zoom bombing that we saw were not what it ended up being, which turned into a kind of political and ideological war of racism and all kinds of other phobias. But at the beginning it was a lot of pranking. Students dropping links to their classes into chat apps saying, “Hey you know, we’re gonna be talkin’ about this thing, like, why don’t you come in and pretend to be a student.” And students were using their phones to video tape themselves invading classrooms and then uploading them to YouTube.

And it was pretty funny, I’m not gonna lie. My favorite one was this video of a student just interrupting the professor and saying, “Hey, can I just pay you for an A? My other professors are lettin’ me pay them. I’ll give you three grand, we’ll call it a day.” And the professor’s just like, what is going on? Are you even in this class, right. And it’s just kind of jokey and hoaxy. But it was a way of people coping with the kind of moment, trying to assess what was going on.

And then you saw more vicious use cases of Zoom bombing, where black women, black women professors were being targeted. You had instances where LGBT groups were being targeted, Alcoholics Anonymous… And it went from being pranking and hoaxing into something much more…well, the only word I can describe is disgusting.

And what it prompted, though, was a rapid change in the technology itself. Zoom didn’t just change their settings, but they really had to interrogate the entire system, even thinking through where their servers are based and what kind of privacy protections they would need to put into place. But what’s interesting about that is because Zoom had a closed business-to-business model and it wasn’t necessarily like social media is, just out in the world for all to use, they were able to install these changes without an immense amount of blowback from the public. But when we see social media companies try to deal with some of the more terrible use cases…racist use cases, transphobic use cases, things grind to a halt. And we’ve seen over the course of this last summer even instances where social media is trying to cleanup medical misinformation in order to prevent poisoning as well as people taking unnecessary risks. There’s been pushback against that as well.

And so it really has a lot to do with who the customers are, and who the technology company thinks they’re serving in terms of how they envision what is possible for the design of their systems. And in moments of pandemonium, or as Foucault might call it “epistemological ruptures” or paradigm shift, we see technology become much more flexible and malleable to the situation than they may have been in other situations that didn’t feel as critical as they do right now.

And so what you’re living through in this moment is a really rapid succession of technological changes that many of us are just you know, every day waking up to and being like, “Wait, what happened? They did what? Didn’t they say they were going to do this other thing?” You know, and so as we as a research team try to reckon with this, we also have to think about well like, methodologically how do we capture this, and stylistically, theoretically, how do we know what to look for?

And so, I always turn back to the work of Chris Kelty, who was my post-doc supervisor and someone who is an anthropologist and information studies scholar at UCLA. And he wrote this book in 2009 called Two Bits, and it’s really also indebted to the work of Elinor Ostrom on governing the commons. But he talks a lot about how to produce moral and technical order. And he is studying free software. And so thinking with his framework, I’m really drawn in by this quote:

Geeks fashion together both technology—and principally software, hardware, networks, and protocols—an imagination of the proper order of collective political and commercial action, that is, of how economy and society should be ordered collectively.

Chris Kelty, Two Bits: The Cultural Significance of Free Software

And what he’s really trying to say here is that the way in which our technology is built encodes a vision of society and the economy. And in building software in this way, we end up, recursively, with a society that in some ways mirrors that technology, but in other ways the technology really is distorted by the conditions of its production.

And so thinking through that I wrote this paper with Anthony Nadler, Matt Crain, about Weaponizing the Digital Influence Machine: The Political Perils of Online Ad Tech. This was like a year and a half ago or so. And we came up with this concept of the digital influence machine, which is the infrastructure of data collection and targeting capacities developed by ad platforms, web publishers and other intermediaries, which includes consumer monitoring, audience-targeting, and automated technologies that enhance its reach and, ultimately its power to influence.

And so instead of thinking about just social media, we’re thinking about the architecture of advertising that spreads across the Web and social media as a way to understand well how is the Web or the Internet reflecting back then its vision of society. And how is that infrastructure specifically about the reciprocity between data collection and then circulation of information through targeting, how is that encoded and what forms of power are then able to leverage that digital influence machine in order to produce…let’s just call it social change?

But that power is something that sociologists, comms scholars, every one of us I think on this webinar today are really interested in understanding. Because I’m not making the case that every instance of misuse of technology is the fault of some company. What we’re actually trying to understand is as this technology scales, as it develops, what kind of social imagination is animating design decisions? And who can either purchase power in the system, or wield it by virtue of having very large social networks?

And so we’re not necessarily interested in all misinformation, or all instances of bad behavior online. What we’re interested in is how do certain kinds of behavior scale, how do people learn about it, how do they adopt that kind of power, and how do they wield it against a society that is using the Internet by and large for entertainment, using it to learn about things, using it to read the news, using it for their education, right. A lot of things are now passing through the Internet as a kind of an obligatory passage point. But in doing so, in digitizing most of our lives and now even most of our everyday lives during the pandemic, what kind of differences in power are manifesting themselves, and to what ends then are we as a collective asked to shoulder the burden, or to pay the price for the production of this particular kind of moral and technical order.

So I asked myself, if we’re in this situation and it’s…now I would say easier than ever to conduct propaganda campaigns, to hoax the public, to perform different kinds of grifts, I’m drawn into thinking about how at the beginning of the pandemic there were were over a hundred thousand new domains registered with “COVID-19” or “coronavirus” as part of the domain address, part of the URL. So, what ways in which…are we paying for this kind of media ecosystem information environment that ultimately doesn’t seem to be serving our broadest public interest, which for me is at this stage at least with the pandemic, being able to access accurate information.

So I’m thinking a bit through the lens of Siva Vaidhyanathan’s book Antisocial Media, thinking about well who pays for social media? And we know the little adage of course is if the product is free, the product is you. But the product actually isn’t free. Advertisers are the ones that pay for it, and then you are the consumer of advertising through social media.

But Zuckerberg said this really interesting thing. He said, I don’t think it’s right for a private company to censor politicians in a democracy.

So this is during his Georgetown speech. And I thought yeah, I can agree with that. And like, private companies shouldn’t be censoring politicians in a democracy. Cool.

But also, like, this seems really like a platitude. It doesn’t seem… It doesn’t— It resonates, but it doesn’t…it just hits different when you start to think about well what do they mean by censoring politicians. And what do you do when you create the conditions by which politicians can—or any ol’ person can speak to millions at scale? What happens when you are not necessarily accounting for the fact that you have built a broadcast technology that is allowing for misinformation at scale?

And so that was my initial thoughts on this. And one of the things that I was drawn into in early January 2020 was a bit of a reversal in Facebook policy, where they write, In the absence of regulation, Facebook and other companies are left to design their own policies. We have based ours on the principle that people should be able to hear from those who wish to lead them, warts and all…

And that kind of statement, “warts and all,” made me wonder a bit about well how are they really gonna reckon with the way in which different politicians are using their system, not just the “organic”—quote, unquote—we could get into all kinds of discussions about why that metaphor is wrong. But what is it they’re actually trying to get at when they say “warts and all” when it comes to politicians who are using both their advertising systems and other forms of social media marketing to essentially delude the public, right. To not just put forward a political position, but also to gin up all kinds of suspicion… And of course this is before the pandemic really takes root. But you know, this seemed to be their reaction—Facebook’s reaction to the situation that we were in was basically like, “Well, if you don’t regulate us, we’re just gonna you know, kinda have to let it have to happen.”

And then the pandemic hits, and Facebook realizes that they’ve become this central figure in not only medical misinformation campaigns but also in this effort to, as Yochai Benkler and Rob Faris’ group have shown, to make people believe that mail-in voting is insanely corrupt.

And so eventually Facebook does have to change their policies on political advertising. Because they realize that at scale, it’s different. Scale is different. You know, Clay Shirky often talks about more is different, right. And in sociology we don’t understand ourselves as psychologists because we know that more is different, society’s actually different. And so when you’re dealing with misinformation at scale, people who pay the price don’t tend to be the companies at all, but really end up being the people who are information consumers, let’s say.

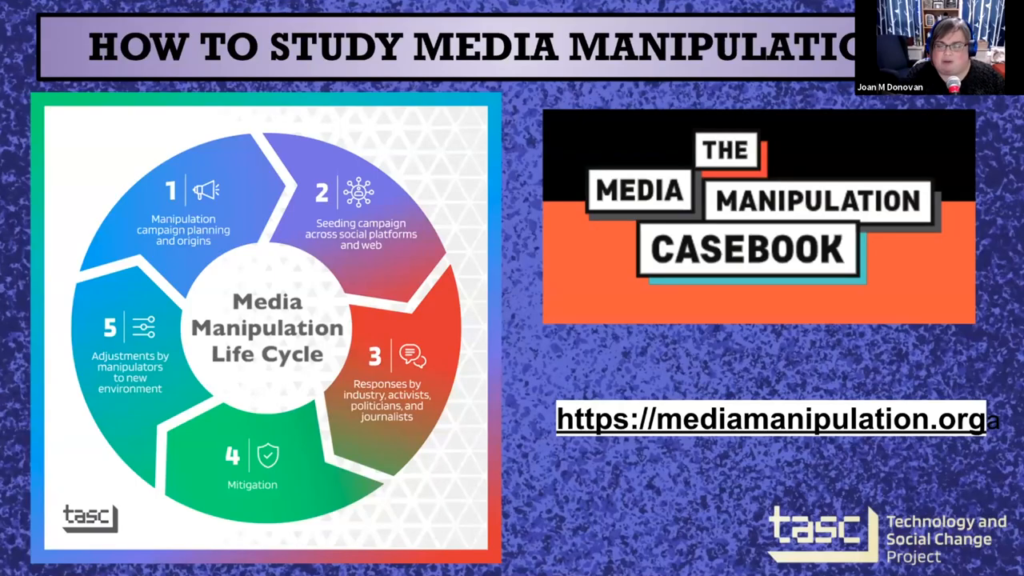

So how do we study this? How do we study misinformation at scale? How do we make sense of it? Our new web site is up now. And what we do is we put together a theory about the media manipulation life cycle, which if you want to study these things we recommend that you look for essentially five points of action: where is the manipulation campaign being planned; what are its origins; how does it spread across social platforms and the Web; what are the responses by industry activists, politicians, and journalists.

This is crucial. If nobody responds to your misinformation campaign, not much happens. You know, 2016, 2017, even earlier than that, Whitney Phillips’ work has pointed us to the fact that this kind of media hoaxing performed by you know, trolls and other folks through 4chan, it had become a bit of a game to get journalists to say wrong things, to try to get politicians or other folks to chime in, to “trigger the libs.”

And so when we’re thinking about how a media manipulation campaign is gonna succeed, we’re actually trying to understand well, who’s going to respond. Because you know, there’s going to be so many…let’s just call them shenanigans online that it would be impossible to moderate that at scale.

Then we looked closely at mitigations. So 2016, 2017, really the big tools of social media companies were content moderation—including take-downs, and the removal of certain accounts. They weren’t really in the business 2016, 2017, of demoting content. There was some removal of monetization. But over the last year in particular we’ve seen a number of different ways in which platform companies are willing to do moderation and curation of content online. And so Stage Four has expanded. But, without any transparency. And so we’re often backing into problems of content moderation as we’re trying to understand the scale and the scope of a media manipulation campaign—we often run into moderation that has not been recorded in any public kind of way.

And then the last thing we look at is the adjustments by the manipulators to the new information environment. So if some action is taken, or if they enjoyed some success, we will see that campaign happen again and again and again.

So if we can answer the question around you know, who pays for social media, and we know that advertisers are pumping money into it and we know that you know, the public is by and large the crop that is being harvested, we have to think about this category of misinformation then a little bit differently. We have to think about well who is actually called into service to mitigate misinformation at scale. I won’t make you suffer through the open hearing that I was part of but it is on YouTube. Not ironically, that is where they air the Select Committee on Intelligence hearings. And we did a hearing on misinformation, conspiracy theories, and infodemics. And I’m just gonna talk a little bit about what I presented in that hearing and then how I think that it related to the Media Manipulation Casebook.

So, when we’re thinking about who pays for misinformation, I’m really thinking about several categories of folks that are professionals that have now started to build their livelihoods and careers around handling misinformation at scale. So journalists…we know the story, many of us are probably involved in this, where our role is one of finding misinformation online, or disinformation campaigns, and then ringing the alarm bell and trying to get platform companies to go on record. This is a new beat for journalists. Over the last several years journalists have really honed skills that are unlike any other, using open source intelligence as well as using other forms of online investigation, even digital ethnography, to get to the bottom of misinformation campaigns.

Public health professionals. I’ve talked to more public health professionals than I have in the span of my lifetime over the last few months, where they are just…deluged by the kinds of…by people who are scared, people who are confused, and people who want to know more about COVID-19 because they saw online you know, that 5G’s causing coronavirus therefore no vaccine will work. They saw online that Bill Gates actually unleashed this on the world and so we need to put Bill Gates in jail and the rest of this will end. Public health professionals have been called in to do quite a bit of misinformation wrangling.

Civil society leaders… I’ve been working with a group of folks through the Disinformation Defense League for the past several months, really focused on get out the vote campaigns, right. If your get out the vote campaign isn’t just about letting people know when, where, and how to vote but really about trying to get them to understand that voting is not imperiled, your mail-in voting is not imperiled, or other forms of voting, or that the machines aren’t rigged, this is the role that civil society has had to take on as a result of misinformation at scale.

And then lastly, law enforcement, public service election officials, probably best exemplified by the recent controversy around the web site operated by CISA which Chris Krebs was at the helm of until he was fired via Twitter. You know, these are the kind of folks that are taking these questions, fielding these questions about voter fraud and misinformation. And so, they don’t have budgets for that. Nobody was like, “Oh yeah, you know what, we also need to have a huge misinformation budget so that election officials can let people know that their votes were counted and that this is the way in which the machines that they used worked, or this is how we verified signatures.” Right, we just… I anticipated it, but for the most part we didn’t anticipate the scale at which this would be occurring.

And so, when we talk about this on our web site—and we have fourteen or so case studies up there, we have about another nine or so that’s gonna go up by end of year, one case in particular around the Ukraine whistleblower, we were looking at the different kinda of media manipulation tactics that were used. And journalists by and large had to really navigate a very twisted terrain of trying to cover the Ukraine story without saying the name of the whistleblower, which was traveling in very high volumes throughout the right-wing media ecosystem. And there were a lot of attempts to try to get center and left media to say this person’s name. And for the most part they relented, and they didn’t cover the disinformation campaign, because of the role and the status that whistleblowers historically play in our society, which is that we should be protecting their anonymity.

As well, the Plandemic documentary, the way that that was planted online, they knew it was gonna violate the terms of service on every platform so they set up a web site in which you could engage with the content, watch the content, but then also download it. And they had a set of instructions that basically said “Download this and reupload it to your own social media.” And this happened thousands and thousands of times, so it was really difficult to actually get that video removed from the Internet and removed from let’s say, prominent platforms, because it’s still on the Internet. But this tactic of distributed amplification, we’ve seen this before. But we don’t have a lot of great solutions to it when it comes to dealing with medical misinformation in particular.

As well, when we’re thinking about viral slogans and the ways in which civil society have had to deal with white supremacist and extremist speech online, we have a case study about the slogan “It’s okay to be white” and the way that it moved from flyers that were planted on college campuses with a very plain message. There was no indication of who was doing this other than if you knew where to look on 4chan, you knew that it was a campaign by white supremacists and trolls that basically asked people to put this flyer up in public places that just says “It’s okay to be white.” In Massachusetts somebody put up a banner over the highway, trying to get media and other folks to take pictures of it. And this kind of viral sloganeering is something that civil society organizations have really had to reckon with and call attention to so that people understand every [utterance] of this slogan is meant to create the conditions by which people would discuss racism and race but through the lens of whiteness and to try to normalize discourse about white identity.

And then public services, one of the case studies that we have up there is a case study about Maxine Waters’ forged letter. The letter looks as if— I mean, there’s a lot of digital forensics that make you realize very quickly that this is a forgery. But it was a letter saying that— It was a letter “written from Maxine Waters,” to a bank basically saying “If you donate a million dollars to me I will bring—” I think the figure was like 38,000 immigrants who are all going to need mortgages to this area. And so “if I win, then we all win” kind of thing. And this letter was planted by her opponent, and then through the uses of bots and other kinds of automated technologies was promoted online.

But it actually ended up with the FBI having to get involved. And we’ve seen numerous instances now, especially during the pandemic, where law enforcement are now being called up with these rumors and they’re being asked you know, will you step in and deal with, you know, antifa setting fires in my neighborhood? And law enforcement are like, “Where is this coming from? Like why now are we being asked to deal with misinformation at scale and these kinds of rumors?” And of course election officials as I mentioned earlier are also being called into the fray.

So what does it all mean? I wrote in MIT Tech October 5th of this year—of…still this year; yeah, it’s December 1st, rabbit rabbit. I wrote this piece called Thank you for posting. And I make this argument:

Like secondhand smoke, misinformation damages the quality of public life. Every conspiracy theory, every propaganda or disinformation campaign, affects people—and the expense of not responding can grow exponentially over time. Since the 2016 US election, newsrooms, technology companies, civil society organizations, politicians, educators, and researchers have been working to quarantine the viral spread of misinformation. The true costs have been passed on to them, and to the everyday folks who rely on social media to get news and information.

Thank you for posting: Smoking’s lessons for regulating social media

So if we were to try to restore moral and technical order, I got like a list, I got lists all over the place of things that I think we could do, but I’d love to discuss some of these with you.

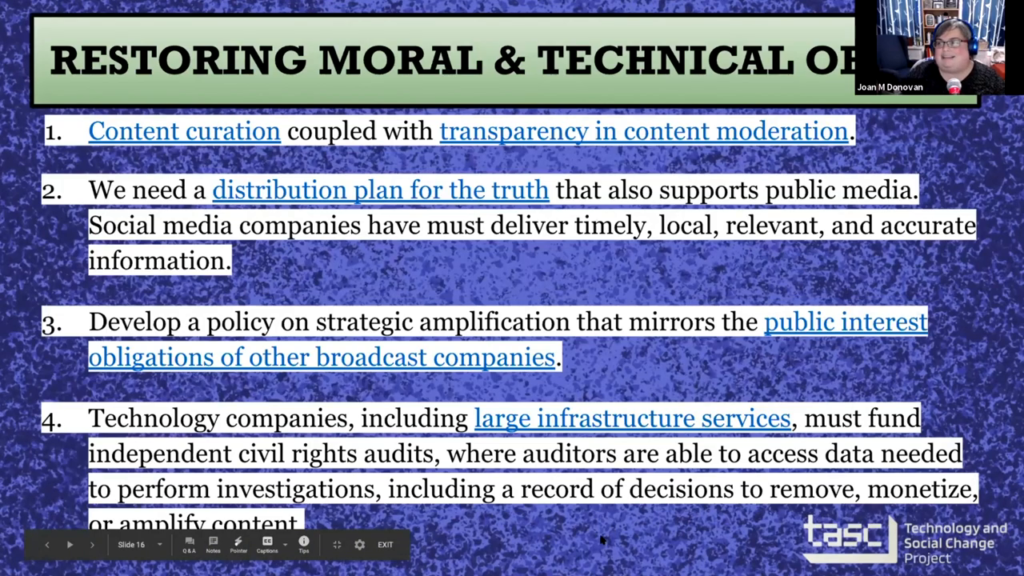

I think we need a really good plan for content curation coupled with transparency and content moderation. I’ve argued in the past for hiring 10,000 librarians to help Google and Facebook and Twitter sort out the curation problem. So that when people are looking for accurate information and they’re not looking for opinion, they can find it. You know, if you think about Google search results, the things that become popular are the things that are free. Anything that’s behind a paywall is not something that people are gonna continue to return to. And so as a result, Google search becomes the kind of quality of a free bin outside of a record store, right. Every once in a while there’s a gem at the top, but not usually.

We also need a distribution plan for the truth that supports public media. And social media companies must deliver timely, local, relevant, and accurate information. We’ve seen this happen with pandemic information, where there’s lots of these like yellow banners that are showing up on web sites. That’s not a plan, that’s like…a sticky note. So we need something else.

We need to develop a policy on strategic amplification that mirrors the public interest obligations of other broadcast companies. When we think about strategic amplification, if something is reaching 50,000 people, when we think about broadcast and radio…we have rules for that. So when something is reaching a certain amount of views, or a certain amount of clicks, or a certain amount of people routinely, especially if it’s a certain influencer, there has to be some kind of measure that will help us understand when misinformation, or hate speech, or incitement to violence is circulating at epic volumes; what is the protocol that should exist across social media sites.

And then lastly, I think something that fell out of view but is still very important is that technology companies, including large infrastructure services, must fund independent civil rights audits where auditors are able to access the data needed to perform investigations, including a record of decisions to remove, monetize, or amplify content. And so we need much more transparency and this might come in the form of an agency that can deal with this.

So these are four of the ideas that I’ve come up with off the top of my head, wrote on a back of a napkin and didn’t give much thought to. I’m kidding. I spend my whole life steeped in this nonsense. And the only thing that sustains me through it, I think, is knowing there are people like the good folks at Berkman Klein that want to deal with these problems, and want to deal with them responsibly but also understand that these are problems that harm different groups of people disproportionately, and we’ve got a really great whitepaper up on media manipulation.org from Brandi Collins-Dexter specifically about how COVID-19 misinformation manifests in black communities online.

And, so as we deal with the pandemic, as we deal with the questions of moral and technical order, we’re really just striving to answer do we have a right to the truth. And if so, how do we get there? Right. And so that’s the thing that’s been my pain for many, many years now. But I’m hoping that through…you know, the next several years of an administration that is uh…potentially, I don’t know—I don’t even know—sympathetic to dealing with harassment of women, the ways in which certain communities are underserved online, particularly black communities, dealing with the kinds of misinformation that’re pervading Latino communities as well, that we will get somewhere on some of these issues. But it’s going to be a very very long process.

So I just want to thank my team, and the folks that help me think through these problems every day. And we are now open for questions.

Moderator: Awesome. Thank you so much, Joan. So we definitely have a bunch of questions coming in, and we’ll start with some of the ones that are getting some additional thumbs up, just as those seem to be the most compelling from people. So one is from Madeline Miller and states, “As a student currently doing a professional degree in library and information science what can I do about being part of a team of 10,000 libraries working on community misinformation?”

Donovan: Yeah. I think like— You know, I would love for the ALA to step in and really create a program that allows for—at conferences for this kind of thing to develop. As well, you know, there have been different efforts to build a digital public library. But I do think that we need more librarians’ voices embedded in industry. And it pains me to say that because ideally, as the utopian that I am, we would build a broad public infrastructure that deals with these problems and I’m like, very excited for Ethan Zuckerman’s new lab at UMass to deal with some of these issues. But for now, we have what we have. And we do need folks to start to think about well, if we were going to take you know, let’s say twenty consistent disinformation trends and deal with them specifically, how would we reformat search so that the first three to five things that people see are actually things that have been vetted.

Francesca Tripodi has this really great report at Data & Society on searching for alternative facts. And one of the things that she discovered in her you know, ethnography was that a lot of people believe the thing that they see first on Google has been fact-checked in some way, or vetted in some way, or is the truest thing, and it’s not. And so I think there’s a lot of work to be done by librarians to sort out our information ecosystem and make good models for how we would advance a knowledge-based infrastructure rather than a popularity or pay-to-play infrastructure, which is what we have now.

Moderator: Alright, thank you. So this is one that came up early and I think it’s a question that often comes up in this realm. And this is like how does your definition of disinformation differ from propaganda? And I might add to that you know, how is this challenging given that those are probably…for lack of a better word unstable categories with many of the different entities that we’re looking at here?

Donovan: Yeah. Yeah. [chuckles] Well, the reason why disinformation is actually an interesting category to work with is because it shows up in…you know, American discourse prior to 2016 as something that is sort of uniquely Russian in the sense that these are kinds of campaigns that are associated with Russian political tactics, information warfare… But as the US starts to figure out that there’s disinformation happening, you get this discourse of fake news. And you know, Claire Wardle did a lot of work to try to tell people not to use that word because it was playing into political divides.

And I’ll give you one anecdote about why fake news was so treacherous to work with, is because when you would talk with designers or technologists at these social media companies, they would just say, “Well, you know, fake news…real news…like what’s the difference, it’s information,” you know. And they didn’t understand what we were actually talking about. Which is to say that they were using these popular definitions, and Trump had obviously made an enemy out of The New York Times and CNN by then, saying they were fake news. But what we were actually talking about was something that Craig Silverman had looked into when he was I think a Nieman fellow, where there were these cheap knockoff web sites that were made to look like news but were really just about clickbait and they’d come up with any old headline that would make you want to click through the content.

So fake news for us was a technological problem brought about by the monetization of advertising, where you had these fake web sites. But then the politicization of that term made it seem like well, when you’re talking about fake news, you’re talking about a political category. And so when disinformation started to sort of become something you could talk about and not have it be necessarily only aligned with discussions of Russia, it felt like a better fit than dealing with particularly the fake news discourse.

But then on top of that, when Network Propaganda came out, of course, propaganda got put back on the map in a serious way to look at the phenomenon of media elites who were using both the online and the broadcast environment in order to create a zone of information that was politically motivated.

And so for me, when I think about propaganda I’m thinking specifically about you know, the way in which that book positions networked propaganda as a kind of tool of media elites. But with disinformation, for us as research team we’re really trying to look at the incentivization. And we deal a lot with fringe groups. We don’t necessarily… Of course we’re avid, avid watchers of Tucker Carlson. But insofar as he’s like the shit filter, which is that if things make it as far as Tucker Carlson, then they probably have much more like…stuff that we can look at online. And so sometimes he’ll start talking about something and we don’t really understand where it came from and then when we go back online we can find that there’s quite a bit of discourse about “wouldn’t it be funny if people believed this about antifa.” So yeah, so that’s… I know it’s not a clean answer, but that’s sort of how we arrived at where we are.

Moderator: Awesome. Thank you. So, to follow with that, I think particularly as you start to talk about kind of the media and those distinctions, the next question we have is… I know this will be a more complicated answer. Have any social media companies expressed any willingness to work with groups like yours on squashing misinformation on their platforms? And I guess I’m thinking about that particularly as you were describing kind of the fringe groups and how they’re taking advantage of, and often the media companies are profiting from that advantage.

Donovan: Yeah. I mean, we’ll take meetings with anybody, we just won’t take their money or data, right. And so the idea here is basically that you need to have a pretty… For my team especially, we have a pretty strict rule about how we get our data, the way in which we engage with platform companies—or any company. We will take meetings literally with anyone, right. Because for us it’s not about…it’s not about them getting us to see it their way. It’s about us getting them to see it our way, right. Education when done well is we all arrive at a shared definition of the problem. And so for us, engagements with different companies really are about showing them something they couldn’t see, because they were stuck in a specific mode of thinking.

So for example if we think about all of the different ways in which research could’ve been done about disinformation in the elections. I think the approach of the Berkman Klein team around you know, looking at mail-in voter fraud very deeply using Media Cloud was the right approach. They didn’t you know, go out and solicit a bunch of information and funding from platform companies that would mire them in questions of their allegiances and whatnot, they just did what they knew how to do. And they were able to, like many of us that remain fairly independent, were able to see that the question wasn’t really about how many misinformation campaigns we were going to see, big or small, it was really about having the best knowledge we could have of the ones that were gonna have what looked like the most amount of impact because they had a couple of signature aspects to them, which is that media elites were picking them up, political elites were pushing them, and they were forcing a public conversation that wouldn’t have happened if not for the design of our media ecosystem operating in this way.

One of the things I don’t think any of us could have predicted, though, was the reaction for instance of large-scale media corporations like The New York Times or The Washington Post, or even The Wall Street Journal, not to pick up that political propaganda and parrot it back out, especially during the time of the, you know, dun dun dun, the Biden laptop story.

So I think that when we as research teams engage with industry, it’s really, really, crucially important, I can’t underscore this enough, to go with the method that you know. And to go with the mode of analysis that is most authentic to what it is that you’re trying to study. So for us it’s mostly qualitative digital ethnography. Like we watch the content, we understand who the players are, we understand the scene, and we take that pretty seriously. And so as a result, we don’t get stuck in you know, questions about oh, did this have any impact, or did this do that, or blah blah blah, or like— You know, what we can show very cleanly is these are the progression of facts, and we can show empirically how these things scaled, and then we can look at the kinds of reception and mitigation attempts that platform companies have had. And then we can evaluate them based on the ways in which manipulators either choose to abandon that project, or they choose another route. And so that’s different from other research houses that do very similar kinds of things.

And I think the other challenge journalists have is a very similar one, which is none of us want to get stuck in the role of becoming like, an arm of the industry just doing content moderation. That’s not what’s an interesting piece of the puzzle. For me, the interesting piece of the puzzle, and this is probably just cuz I’m a nerd, is like, how do we make sure people can access accurate information and make decisions about their lives based on that information. As well, like, I also wanna have a little bit of fun. So I enjoy a good prank, and I enjoy a good hoax. But I think that by and large when we’re dealing with misinformation at scale, it’s a feature of these industry practices and therefore we can’t assume that the industry is gonna be able to see itself for what it is.

I think we have time for maybe one more question.

Moderator: Exactly what I was thinking. So, this one I think ties along with that last one and is a good kind of wrap-up question from [Charmaine?] White. “Can you elaborate the concept of a distribution plan for the truth? How is it possible for social media companies to deliver timely and accurate information when communications on them are instantaneous in real-time, and the number of contributors to these networks is every-expanding?”

Donovan: It’s a hard problem and needs more research. And that’s why I really value the work of librarians on thinking through these kinda of taxonomies that we’re gonna need, and the kinds of ways in which we might want to hold out certain categories. I’m thinking here of Deirdre Mulligan’s work on rescripting search. She’s got this beautiful paper about do we have a right to the truth. So what happens when you Google “Did the Holocaust happen?” So back when she was writing her paper…terrible things happened when you Googled “Did the Holocaust happen?” You were actually brought directly into anti-Semitic groups who would you know, post literally every single day anti-Holocaust, anti-Semitic content.

And this is an experience I had as a researcher looking at white supremacists’ use of DNA ancestry tests. It wasn’t the case that when you were looking up certain kinds of white supremacist claims that you were given information about white supremacist groups and why they were bad. And the SPLC does a really good job of tracking that, it just wasn’t rising to the top of Google. What was were…you know, white supremacist groups like Stormfront. And so for me it was really important to think through those questions of well, what do you get when you search for X? What do you get when you search for Y? And then how do those algorithms reinforce that?

danah boyd and I wrote about self-harm. And for a while if you were to look up how to injure yourself, you wouldn’t just get you know, tutorials, you would also be reminded that you searched for that over and over and over again, on YouTube and Instagram and other places that didn’t really have great restrictions on that kind of content. And this goes back to you know, early discussions about Tumblr and pro-anorexia blogs.

And so I think now is the point to understand that we’ve reached a kind of critical mass with social media and dealing with information at scale is just profoundly different than dealing with rumors or hoaxes that kind of stay local. Because social media companies have focused for so many years on increasing scale, increasing information velocity, we now have to have a bunch of different professionals dealing with it in like, really slapdash kind of ways. Like the ways in which journalists have had to take up the problem of media manipulation because they have been targeted by it, the way in which election officials have had to deal with it this year. It’s beyond a kind of quick technological fix. We actually need a pretty robust program to deal with the curation problem so that when you do search for how to vote, you get information about what’s particular to your area.

And it’s only recently—like I cannot express to you enough how recent it is that these companies have been willing to make those changes. Prior to that, it was like if you asked me in 2016 if we were going to get any traction on dealing with these white supremacists that were organizing online, that were rallying at Trump rallies, meeting one another, growing their ranks, expanding their podcast networks, I woulda said no, absolutely not; these companies are completely unable to face what they have built because they didn’t think about the negative use cases. They didn’t think about how different people, fringe groups, would rise to the top and have an incredibly outsized impact on our culture.

The question of propaganda then comes into full view as Trump kind of…pardon the meme but assumes his full form as the president who is trying to defend himself from a lost election. This has just kind of thrown everybody on their heels in this field, trying to map and understand what the real problem is. I was talking with Jane Levchenko at BuzzFeed and she was saying, “I did forty-four debunks in two weeks and I’m tired, and maybe it’s not working anymore. Maybe you can try to debunk everything but it’s just not going to hold. The gates again have broken.”

And so we just…we need to have more thinking of course, and like, as a nerd, more research. But I do think the possibilities of solving this problem lie between these different professional sectors. And that’s why I think the multidisciplinary approach to this problem where we try to get everybody’s concerns on the table, we try to understand how to navigate that, and then with a little bit of help from groups like Jonathan Zittrain’s Assembly project, we can start to have those deeper conversations that ask the question you know, how do we get beyond misinformation at scale, and whose responsibility is it, and how much is it gonna cost. And how do we end up with the Internet that we want rather than this like…thing that we…you know, the thing that we have, which currently isn’t working.

And the public health implications right now are really where my mind is at because ultimately, this kind of misinformation at scale, politicized medical information around masks, around cures…this is like…this is gory stuff. Because you know, we’re gonna look back on this moment historically and every one of us is gonna wonder did I do enough, and how could I have done better. And that’s why I think it implores us all to try as much as we can to get involved, to think through these problems and to— And our method is thinking with case studies, because we want to think about things in-depthly and then we want to extract from them higher-order definitions and principles.

So, that’s where my mind’s at. But I appreciate everybody tuning in. We’re gonna have several misinformation trainings starting every month starting in January. And we’re going to have lots of opportunities for people to write for Casebook as well. So I’m really looking forward to that as the next iteration of this project.