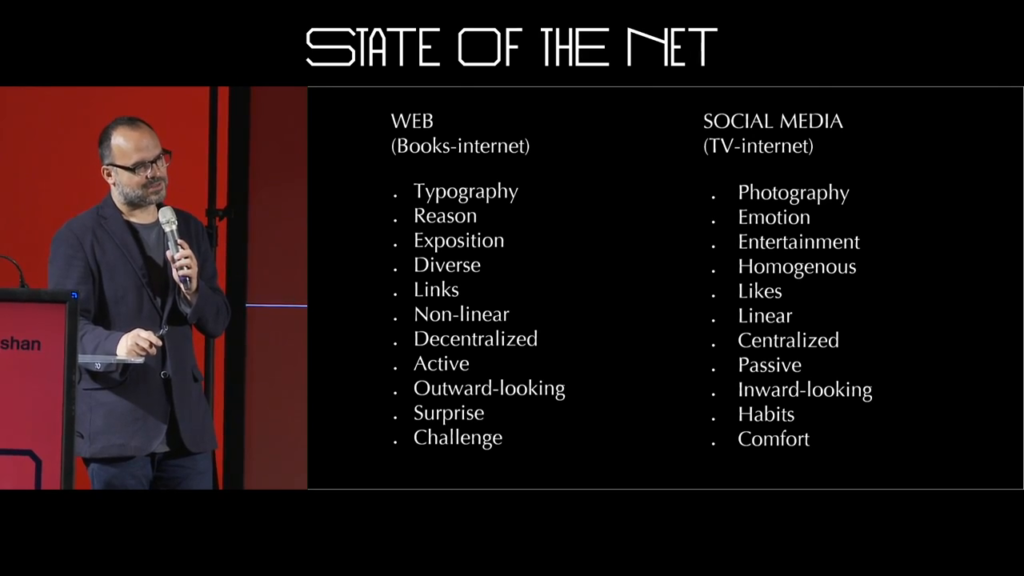

Hoder Derakhshan: So things have a…little changed. This is a summary of our change now.

I’ll give you a few minutes to see it. It’s very sad.

It sometimes also summarizes this shift, the wider shift that I’m talking about, which is the departure from the Enlightenment and its ideals to an era we can comfortably call post-Enlightenment, where briefly…I think the first two lines are the summary of this shift. From text to images, and from reason to emotions. There’s also another way to define it that I will later on discuss.

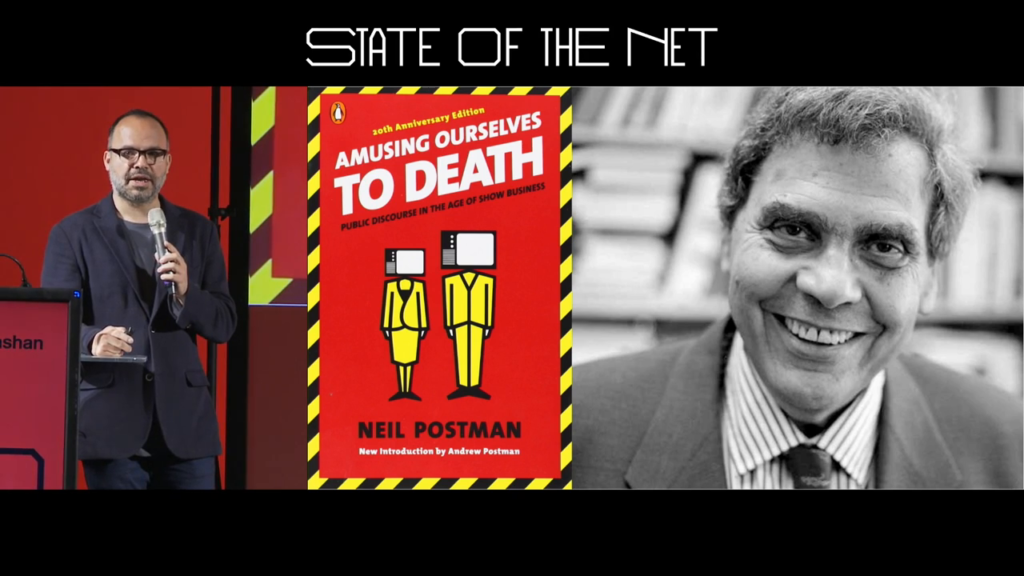

So. This is why Neil Postman is very important. Because he talks about a discursive shift that has happened since the emergence of television. And his obviously very famous book Amusing Ourselves to Death is again, after almost I think thirty years, very important to read and I encourage everybody to read it again. It was published in 1985 when the television was at its height of popularity and influence, and it was going to capture the whole public discourse. Which was very important and true at the time and this is why this book was crucial. But then the Internet suddenly emerged around mid 90s, early 90s, and it disrupted this empire of television that was being formed.

So, now that television has recaptured that area that the Internet had taken from it, I think it’s also important again to look at his arguments, which are basically as the subtitle suggests, the “public discourse in the age of show business.” He looks at television as a discourse, not just as a medium. And I think if you want to understand what that means look at Trump as a TV product who won, using television without spending that much advertising money. He won the election in the most televised society in the world, and now he’s conducting politics through television. This is the most interesting part. What he did last week, or a few days ago in North Korea, was just a TV show. It wasn’t anything substantive. He hadn’t signed any agreement. He didn’t reach any agreement. It was just a show to portray himself as somebody capable of reaching agreements with people whom Obama couldn’t reach an agreement. He does the opposite stuff of anything that Obama has obviously done.

So that’s what I mean by television as discourse, where religion, politics, sports, entertainment, all aspects of our lives are becoming not just reflected by television but they also gain meaning from television. The way many of these discourses happen is very much like something that television dictates or gives meaning to.

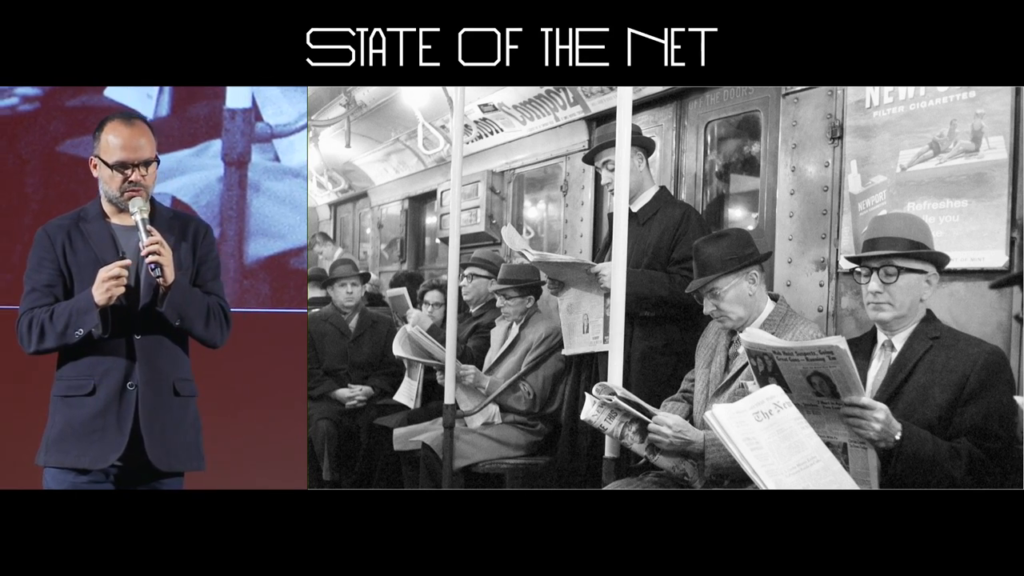

So, this starts another discussion about the future of news, or the future of journalism. What is weird in this picture? Tell me.

Yes, there are print newspapers—people were reading a lot of these print newspapers. There’s also something else. Exactly: hats. And they’ve both disappeared. But there is a relationship between them. Yeah, some some people still wear them. The same way that some people still read print newspapers. They’ve lost something, and that’s why they don’t exist anymore. They’ve lost some of their functions or relevance, probably both of them.

Because I think this is the end of the news. Not the end of journalism, end of news. And I think the whole discussion about business models, or quality, or trust, or ethics are secondary to what is the real problem, which is a cultural problem and a social problem.

There are two arguments. One is that globalism is in decline. News was always a global activity. It gave the middle class at that time for two centuries a kind of global identity, a globalness. That is in decline as you can see the rise of identity politics, the rise of everything local—local breweries, local products, local markets. Localness was not trendy for a long time in the past two centuries, after the emergence of telegraph, I think. Which began the whole process of globalization. So one of the main functions is gone, of news.

The other, which was drama, is also gone. News used to be a very major source of drama in people’s lives before. And I’m talking about even before cinema. Before obviously television. Before satellite televisions. And, obviously before computer games and Netflix. These have replaced news, to many people, as the main source of drama and that’s the other function, the second function that’s sort of gone from news.

So, the idea of time is disentangled from news, in a way. Because on the one hand you have notifications and updates that can be sent to you. At any time. They don’t find any kind of time limit anymore. And on the other hand you have very long-form pieces of journalism which are not that much tied to time as they used to. For instance, many of these revelations could be published anytime. They could’ve taken years to produce and they could have published yesterday or they could be publishing in a few years. And this is another aspect of what’s happening.

So when you bring in the larger idea of the post-Enlightenment when it comes to news and journalism, we reach another summarization of what it means. This is the era of faith, unfortunately. And anything that’s related to facts is in decline, including journalism, including news, including science, including even democracy in a way. So, we shouldn’t be that much surprised, in a way.

Democracy’s very important here, because it’s not only a consequence of this process or this departure from the Enlightenment, but also it’s one of the causes. Because the decline of democracy has led in to this televised show which is sometimes called “elections” in some countries.

James Carey, an American scholar, is a brilliant thinker. He was the dean of Columbia Journalism School for a few years. He comes from I think a background of sociology and communications and he’s very smart. He, in this…this is one of the greatest books that has collected some of his essays. [James Carey: A Critical Reader] In one of his essays, he defines journalism as democracy. This is amazing. Because obviously everybody knows that democracy and journalism help each other, but what he says takes the whole debate to another level. He says democracy is a journalism, because they are both about one thing, which is public conversation. That’s the definition of democracy and journalism—two names, he says, for the same concept, which is public conversation.

So, what is going to happen now with the demise of text, the rise of images, with the demise of reason, and the rise of emotions? Is there any hope that we can still do or incite public conversation, which means we will keep our democracies going on we will keep journalism going as well? Is there any hope for that? I would say yes but it’s quite limited.

One path is literature. So, some of this long-form journalism can be actually published as books, as a nonfiction literature. They don’t have to be published in magazines or newspapers. And I think actually even financially they would be more viable if they are published that way sometimes. So that’s one possibility.

Another possibility’s cinema. And I’m not not talking about fiction, necessarily. Fiction can also be journalistic if it’s based on real issues, if it creates a public conversation. And there are examples of films that have managed to do that. But I’m more talking about non-fiction cinema, which is documentaries. And I don’t think it’s a coincidence now that there are so many more documentary makers, so much money that used to be in text and print journalism is now gone towards video journalism and documentaries, and Netflix is growing so rapidly, and people are watching so many documentaries on Netflix. How many people have watched a documentary on Netflix or another web site in the past week? Wow. That’s impressive.

So this is exactly the equivalent of you reading you know, probably a whole issue of The New Yorker. I don’t think people have time to read that much anymore these days so they put that time into documentaries and that’s one of the bright spots now for the future of journalism.

This is the essay that I published a couple of weeks ago about what the demise of news and the end of news means, on medium.com if you you’re interested to read that in more detail.

So, somehow most of our problems are connected to the idea of the decline of the Enlightenment, which was…I mean if you look back at why the Enlightenment actually happened, and how it happened, we would realize why we need to revive it now again. This would be the root problem and this would be obviously the root solution for all of these problems. Because the Enlightenment emerged at a time after the Middle Ages where prejudices and religion had stopped the human brain or human mind to think beyond a very limited area of thoughts and beliefs. It helped it reach different futures, different terrains. Obviously some of them were not very positive, you know. Some of the stuff that started to happen about the environment at the time, for example. The idea of the human being capturing or controlling or dominating anything that is around it also came from the Enlightenment in a way. But then the departure from prejudices and religious dogma and mythologies is also a consequence of the Enlightenment that we need to look into.

So, going back to the Web and to the Internet, what we see now is only a small part of a larger picture, which is this departure towards enlightenment. And it’s not just the Internet, it’s everything moving toward something that is more visual and that is more emotional. And you know, for instance another topic that everybody’s worried about is fake news and disinformation. But that is also related to this idea of post-Enlightenment. And we can’t address this without addressing these two things, because the reason this shift is happening, the main reason this shift is happening, is obviously inequality. Inequality has led into worse education, worse public education systems. It’s led to the collapse of the welfare state. And obviously that has affected the way people see rationality and reason and education. That’s why we are in such a mess and I don’t think there are many people who are looking at it deeply and radically to address these main issues of inequality and education.