When I began this research in 2010, the way I started out with it was by reading over coffee one day a really small article in The New York Times that was actually more of an afterthought piece in the technology section. And it talked about a group of workers in rural Iowa in the United States, in the Midwest, in an area that had been traditionally a family farm area. And these workers were transitioning from family farms which were no longer economically viable in that part of the country and moving into working into call center-like environments for a firm called Caleris. And you can see their website here. This is a screenshot from it from a few years ago.

The workers were performing a number of call center-like tasks. They were answering phones and doing this kind of thing. But in addition to that, they were performing a new form of labor that was going under a number of different names: screening, content moderation, forum moderation, social media management, and so on. And the workers in Iowa were working for just above minimum wage. They were hourly workers. They were working without benefits, which in the US is a significant factor because it meant they were without health care. And as the New York Times reported, these workers were beginning to suffer some psychological issues based on the work they were doing as content moderators.

What they were doing was screening various social media sites as well as other kinds of commercial websites, and seeing uploaded content—user generated content, day after day, image after image, video after video, and screening it for appropriateness for a site. As you can imagine, a lot of what they were seeing was in fact inappropriate, and it was inappropriate on the grounds of it being potentially obscene, pornographic, but also content that was extremely violent. Violence towards children, violence towards animals, adults engaged engage in violence, war zone footage, and other kinds material such as this. And the workers were reporting some difficulty in managing of their ability to look at this content constantly, especially at such a low wage without any type of benefits.

So, I was intrigued by the story. I turned to my colleagues who were all digital media experts, academics who dedicated their life work to studying the Internet and digital media. I myself have been online since 1993 when our social media platform was literally in a guy’s closet on a server, a guy named Jeff. So my sense of moderation was really more around voluntary kinds of activities.

And when I asked my peers and my professors if they’d ever heard of this type of work, two things happened. The first thing is that they said no, they hadn’t. The second thing they said, which is probably what you’re thinking, is, “Well, can’t computers do that?” And in fact the answer to that is no. And I’ll talk a bit more about that.

In the meantime, I visited Caleris’ web page and I was stunned to discover their own tagline, which as you can read up here was “Outsource to Iowa, not India” with this bucolic farm scene that really reflects the reality that’s no longer even in existence in Iowa. It’s all factory farms and agribusiness there.

So, just to give you more of a sense definitionally of what commercial content moderation really looks like, it’s a globalized around-the-clock set of practices in which workers such as the Caleris workers and others viewing and adjudicate massive amounts of user-generated content (or UGC in industry lingo) destined for the world’s social media platforms and interactive websites.

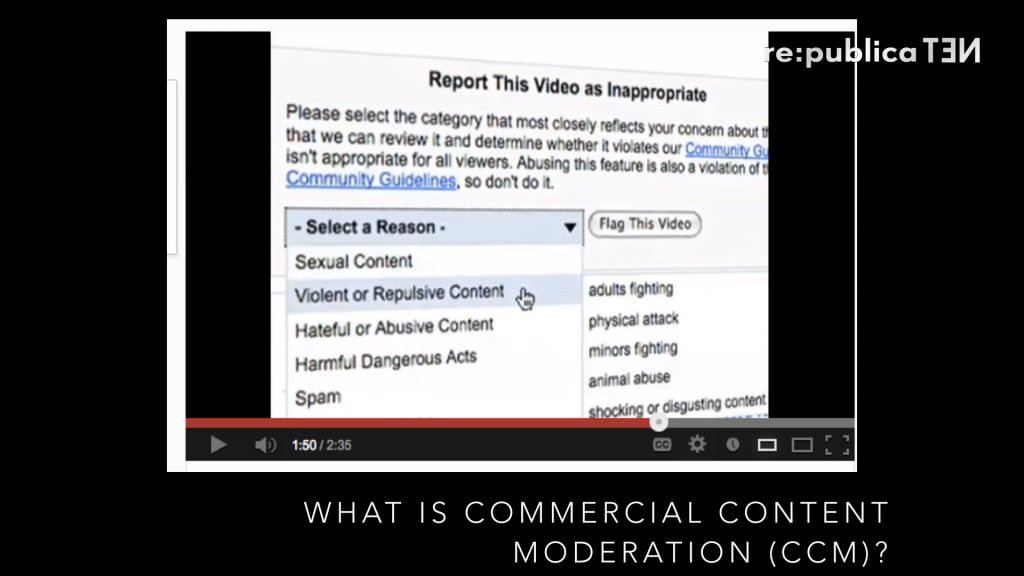

While the workers’ status and remuneration vary widely depending on site and circumstance in the world, there are some features that this work tends to share. Specifically, CCM work is typically unglamorous, repetitive, and often exposes workers to content that is disturbing, violent, or psychologically damaging, all as a condition of the work that they do. This screenshot is from YouTube’s flagging system a few years ago, which you as a user can go to if you come across content that you find disturbing or otherwise inappropriate based on site guidelines, and you can report it. For YouTube, that triggers the content moderation process to begin. So we as a users participate in the process of CCM by our own reactions to the content we see.

So, CCM workers in the course of their work render content visible or invisible, while simultaneously remaining invisible themselves. In the world of CCM, the sign of a good job is to leave no sign at all. And yet the mediation work done by CCM workers goes directly to shaping the landscape of social media and the UGC-dominated Internet that we all participate in, where platforms exist simply as empty vessels for users to fill up with whatever they will, and for CCM workers to act in effect as a gatekeeper between the users and platforms, providing brand protection on behalf of the companies and the platform owners, which they demand.

Companies that tend to utilize CCM services, whether they are the third-party companies that often employ the workers, or the major platforms themselves, avoid talking about their moderation practices. In fact, they’ll often treat it as a trade secret, and they subject their workers to non-disclosure agreements, or NDAs, that preclude the workers from speaking about the nature and conditions of their work.

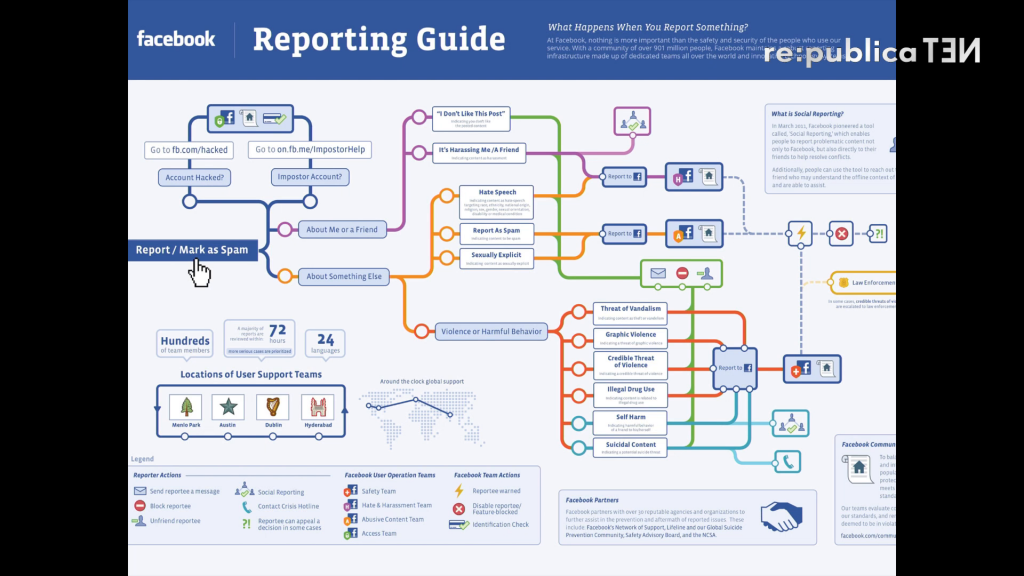

Yet despite the hidden nature of CCM, it is in fact an essential component of the production and circulation of social media. On the screen here is a leaked document from a number of years ago through the third-party firm oDesk, a microtask website that had this reporting guide from Facebook. And again, following the circuit, you can see the type of material that is often found in the CCM process and then therefore get an idea of what those workers are exposed to, even though they’re unable to discuss it freely because of their NDAs.

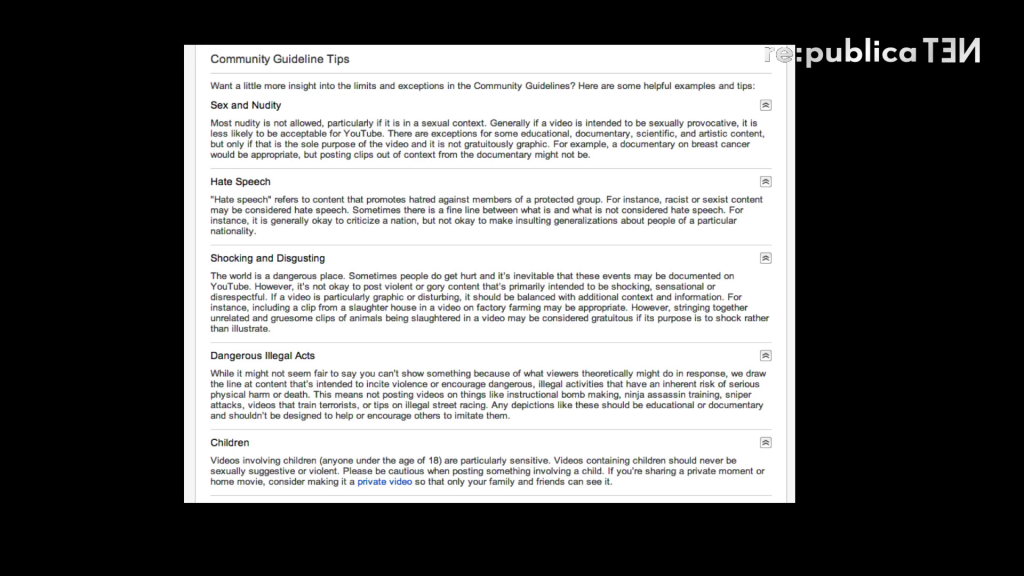

And this is a screenshot from YouTube’s community guidelines. Again, if you want to know what kind of material workers see, go to your favorite platform and look at community guidelines or the other kinds of rules and regulations that govern the UGC that can be included, and you’ll see it there.

So, making decisions about what UGC is acceptable and what is not is actually a highly complex process, as I indicated. At this at this point it’s well beyond the capabilities of software or algorithms alone. Some firms do employ some level batch processing and some measure of algorithmic moderation, but typically this work falls to human agents. And just to give you a sense of the kind of content stream or the volume that we’re talking about, YouTube itself receives over a hundred hours of uploaded video per minute. So, the the enormity of the UGC that is created for each platform is just exponential, if you think about that amount of content per minute.

Some of this will go through machine automation, but the material that’s flagged, usually by people like you and me, will be typically rerouted through a circuit like the one you just saw a few minutes ago to a human agent in some place in the world. And whether or not the screening happens before the content is uploaded, which is the case for some platforms, but typically after it has been posted in most, human content moderators are called upon to employ an array of a very high-level cognitive functions and cultural competencies to make decisions about the appropriateness of such content for a site or platform.

So, in order to do this they must be experts in matters of taste of the site’s presumed audience; have cultural knowledge about the location of origin of the platform and of the audience, both of which may be very far removed geographically and culturally from where the screening is actually taking place; have linguistic competency in the language of the UGC, that may be a learned or second language for the content moderator him or herself; be steeped in the relevant laws governing the site’s location of origin; and be experts in the user guidelines and other platform-level specifics concerning what is or what is not allowed. All the while being exposed constantly to the very material that mainstream sites disallow. And just to give you an idea of the volume of processing, we’re talking about thousands of images a day that these workers are asked to view, or thousands of videos. So the work has to be very quick.

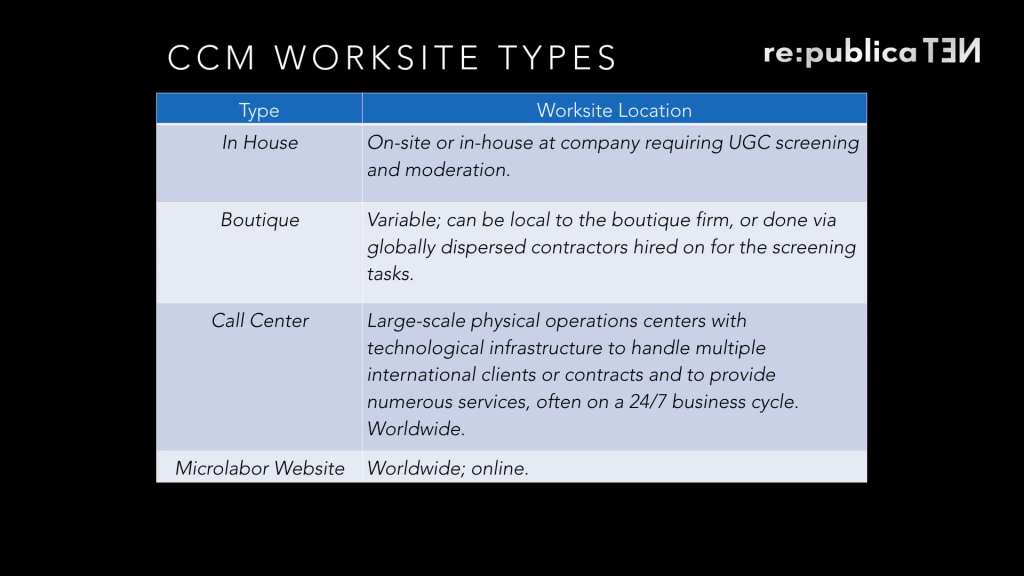

All of that having been said, CCM isn’t an industry unto itself per se. In fact it’s it’s a labor process or set of processes that takes place across a number of industries, and as such is stratified in the way that I have listed here. So, some firms have the capability both technologically and financially to have workers right on site with them. This is the case for many of the major Silicon Valley social media firms. They will have an in-house team, although I should point out that those workers are often contract laborers. So, they will lack the full-timer’s badge. And some workers joke with me this means they can’t access the climbing wall in the lobby of their building. They can’t get the free sushi and kombucha that’s on availability for the full-time workers. But at the same time, it also means they didn’t get the health benefits that full-time workers access. And when we think about the psychological needs of these workers, that is an important issue.

There are boutique firms, social media agencies much like ad firms, that provide CCM-like practices. And they will also even go so far as to seed content that is more favorable. So, they’ll take down the bad stuff for a brand image, and put in content that is positive.

Of course as I mentioned, we have call centers all over the world, and I’ll talk about where those are located.

And finally, we have micro-labor websites. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, Upwork (formerly known as oDesk) and other sites like this, where workers come together in a digital piecework manner, doing one piece of digital labor for one contract, meeting and separating. A lot of CCM work goes on in this kind of environment off for as little as one cent per image viewed, and then there’s absolutely no relation between the firm and the employee after that one screening takes place.

So, I’ll talk to you a bit now about the case of a firm I call MegaTech. This is a Silicon Valley-based firm. I am not able to share with you the name of the firm, it’s real name, because of the ethics guidelines that I’m under as a researcher. But it’s one that all of you know and have used and are probably using now. They have many major global brands and platforms. And it’s one of the firms that from an economic and technological perspective can support a team of CCM workers on site.

All of their workers, although they were contractors coming in from a third party, were required to be college graduates, university graduates with four-year degrees. And they were coming to MegaTech with elite backgrounds from places like the University of California at Berkeley, for example, or University of Southern California, and other off four-year liberal arts colleges. However, they were coming not from science, technology, and engineering backgrounds, but actually the lesser disciplines of the humanities and the social sciences, right. So, things that Silicon Valley wasn’t putting as much value on. And that’s where they were coming into the CCM process from their four-year university degrees.

For those that I interviewed and spoke with, all of whom were in their early twenties, just a couple of years out of the university, the notion that they could get a job in the Northern California Silicon Valley environment was alluring to them, and it was loaded with promise. They went into this work with the hope that they might do CCM for a year or two, and then transition at MegaTech into one of the more lucrative and one of the more well-respected and valued jobs.

But unfortunately, in no case did that actually happen. The workers would come in on a year-long contract. They would do CCM as a full-time job for a year. They would be made to take a three-month break, during which time their employment and financial issues were theirs to solve. And then they could come back for one more contract, after which time they were terminated from doing CCM work for MegaTech at all. So that leads you to question why it is that the firm itself wants people who can only work for two years and then are cycled out.

Nevertheless, for the young people who were doing CCM work for MegaTech, it seemed to be, at least in the beginning, a better option for them than working in the service sector jobs that they thought were going to be available to them upon graduation. And this was in the wake of the 2008 economic downturn in the US. So, they were looking at taking their Berkeley degrees to be baristas and pizza servers in restaurants in the Bay Area and in California, and working in the offices of MegaTech seemed to give them stature and a chance at a better economic future. And perhaps a chance to work in a social media career beyond that.

I can’t imagine anyone who does [this] job and is able to just walk out at the end of their shift and just be done. You dwell on it, whether you want to or not.

Max Breen, 24, Silicon Valley [presentation slide]

Max Breen was twenty-four when I spoke with him. He was a graduate of a four-year liberal arts college and graduated of course with the debt that many American university students graduate with. And this was the case for all the employees at MegaTech. They had these elite degrees but they were saddled with tens of thousands of dollars in debt, and that was something that they were very concerned about. Max was living in the Bay Area with about a four roommates. He was making forty-eight thousand dollars a year with no benefits at the end of the day. Working hourly for that wage.

And Max was a particularly insightful person about the work that he was doing with CCM. He indicated to me that although it he was “trained” so to speak to leave the material that he saw on the job and just sort of tap out psychologically and mentally when he left, it was really difficult for him to do that. And in fact he found himself going home and ruminating about the things that he had seen at work. Images of child abuse, videos of people giving hate speech diatribes, racist content, misogynistic content, violence towards women, violence towards animals. One of the things that Max indicated to me that the most difficult content for him to see was footage coming out of the Syrian crisis and the Syrian war zone that was coming from people on the ground there, who were sending the material to MegaTech, ostensibly for advocacy purposes. They wanted to use the platform to get a wider audience, to share with the world what was going on.

Max was particularly insightful about his platform’s relationship to things like the Syrian crisis. Because if we were to go back and look at some of the kinds of community guidelines that a platform like Facebook or YouTube, or any other mainstream platform has, which MegaTech is, certainly the kind of footage that he was receiving from Syria would contravene all of those rules. It was violence against children, it was gratuitous, it was gory, and it was unrelenting.

But nevertheless, the group above him that made policy at MegaTech indicated to him that in fact the Syrian material would stand. And it would stand on MegaTech and be allowed to be perpetuated. Max himself started thinking about this, because at the same time he was receiving numerous videos from the Mexican state of Juarez, where a serious drug war and drug by violence has been going on for a long time. Max pointed out to me that the case of Syria was interesting because there’s certainly a US foreign policy dimension there. MegaTech being a US company, seemed to be aligning itself with the US viewpoint on the Syrian crisis. At the same time, he noted that the US also had extreme involvement and a relationship to the drug wars in Juarez, and that material was not allowed to stand under any circumstances even though it was coming in ostensibly under the same advocacy rubric as the Syrian footage. And he started to feel some frustration against these kinds incongruent episodes in his work.

You don’t really want to talk about it. You kind of feel like you spent eight hours just in this hole of filth that you don’t really want to bring it into the rest of your life.

Josh Santos, 24m, Silicon Valley [presentation slide]

Josh Santos was another worker. He had graduated from Berkeley and had been working at MegaTech for almost two years, and was ready to cycle out. He referred to his work at MegaTech as being immersed in a hole of filth. And he would be immersed in that hole of filth eight hours a day, forty hours a week.

Both Max and Josh began to have trouble in their private lives with the material that they were seeing. Because of the non-disclosure agreements they were precluded from talking to friends and talking to others about the content that they were seeing at work, and the kind of work they were doing, and therefore the effect it was having on them. But all of the MegaTech workers indicated to me that in fact they didn’t want to tell other people about what they were seeing because they felt that it would be a burden upon them. They all had a sense of altruism. They had a sense that they were making the Internet even possible for us to use.

Some of the other workers I spoke to told me that without CCM work, most of us wouldn’t be able to stomach the Internet for long. Those of you’ve ever had the misfortune to make an errant click on a video that you had unexpectedly stumbled across that was something like a beheading or something like that know what I mean. These workers were engaged every day looking at that content, and then taking it down so that other people didn’t have to see it.

In spite of this, the workers under their NDAs who weren’t sharing this information with partners and with loved ones were having real effects in their personal life. Max indicated to me that he had started drinking a lot more, for example. Another story I heard was of one of the workers, when he would find himself in an intimate situation with his partner, he would be embracing her, they would be getting into an intimate situation, and suddenly an image of a video he had seen and taken down at work would flash before his eyes and he would push his partner away. And when she asked for an explanation, he couldn’t even find the words to share.

So, not only were they precluded in a contractual way from discussing the content that they saw, it was an emotional barrier. And it was emotional barrier that was beginning to cause rifts between them and the people in their lives, isolating them even further in the CCM work they were doing.

All of this leads me to the point to ask about you know, is this basically the Internet we were promised? Is this the digital labor environment that we were promised? And also where are the flying cars, right?

But as many of you may know, since the early 1970s, particularly in an American context, there’s been a shift in labor from the manufacturing sector, moving into so-called knowledge work. Work that would focus on technical work, specialized scientific and other types of knowledge. The very STEM degrees that I was discussing earlier. And an increased importance and predominance of technological innovation. All of this, of course we were told would lead to this:

More leisure time, easier working conditions. And to be fair, CCM work doesn’t put workers in any kind of direct physical harm. It’s not the heavy manufacturing that might cause someone to lose a limb or an appendage. It doesn’t physically harm them, but certainly there are these other outcomes that are actually insidious, and we can’t see them, and that’s what makes them so frightening.

I can tell you that back in the era of manufacturing in the United States, my grandfather worked in the same factory for forty-five years. He never had to check an email off hours. He was never called to be in a 24⁄7 response cycle, as many of these workers now are. And alongside with this transformation into the knowledge society, we’ve seen some other changes, too, that you’re all familiar with. Privatization of state resources, a deregulation of industry, fewer worker protections, a cheapening of labor, globalization process, all of which are part and parcel of the way CCM operates today.

In fact, great geospatial economic and political reconfigurations have taken place to facilitate the obfuscation of the material and immaterial labor such as CCM that underpins the very knowledge economy that we’re talking about, often via these practices like outsourcing and other types of migratory practices.

In the case of the Philippines, which you can see here—this is Makati city, one of the major financial economic centers in Manila—this often takes the form of special economic zones or special industrial zones where firms can relocate and get special dispensation, such as no taxes or really good tax breaks, or they can build infrastructure only for themselves, and provided only for those businesses while they’re next door to areas that have brown outs.

So, CCM work is increasingly migrating to places like the Philippines. And the Philippines, at just 1/10th the population size of India, has now surpassed India as the call center capital of the world. And MicroSourcing is just one firm that solicits for Western CCM needs. You can see here that it advertises as having a whole bevy of workers who have excellent English skills and familiarity with colloquial slang, American slang, and so on. They don’t really go into why that is. I’ll draw that out in a moment. They also offer a virtual captive service for those who might be interested in that, the rather unfortunately-named service.

This is a place in the Philippines called Eastwood City. It’s the first IT cyberpark there. A lot of times what we’ve seen there is a case of extremely uneven development, where we have the cyberparks and other IT sectors looking something like this, while right next door we have this. And this is what I call the paperless office:

Image: Natalie Behring Photography

So all of this is giving us a pretty significant bifurcation and an exercise in extremes. And I want to say it’s not just in the Philippines where we see this. We see this in Silicon Valley, the difference between places like Mountain View where Google is headquartered, next door to East Palo Alto, one of the most impoverished places in that region.

Just a few words about the Philippines, and you’re going to hear much more about that in a moment from the second presenter. But I want to give you some context. Metro Manila itself is comprised of seventeen individual cities, each governed independently. It makes its own rules, by and large. Rules that are quite favorable to businesses like CCM. And it has a population of twelve million people as of 2014, plus all the people who flow in and out every day to do work in what they call BPOs, or call centers as we know them. The call center sector over the past few decades has become increasingly important, and it’s the main a sector beyond the government sector in the Philippines now.

What we’re seeing there, and what we see elsewhere, not just in the Philippines but in this particular case especially, is a series of intertwined and symbiotic relationships among different systems. So, we’re seeing state and governmental policy regimes that are favorable for businesses that are doing CCM and other types of low-level, if you will, digital labor to locate in places like the Philippines. We’re seeing land and physical infrastructure development to support this kind of work and to make these great centers of this kind of work.

And finally we’re seeing, from a labor perspective, availability, preparation, and also processes that all go towards enhancing this. One of the things that the Philippine governmental agency in charge was soliciting companies to come to the Philippines does is they tell you that there are very few strikes in these economic zones. Great for business. I don’t know if that’s great for workers.

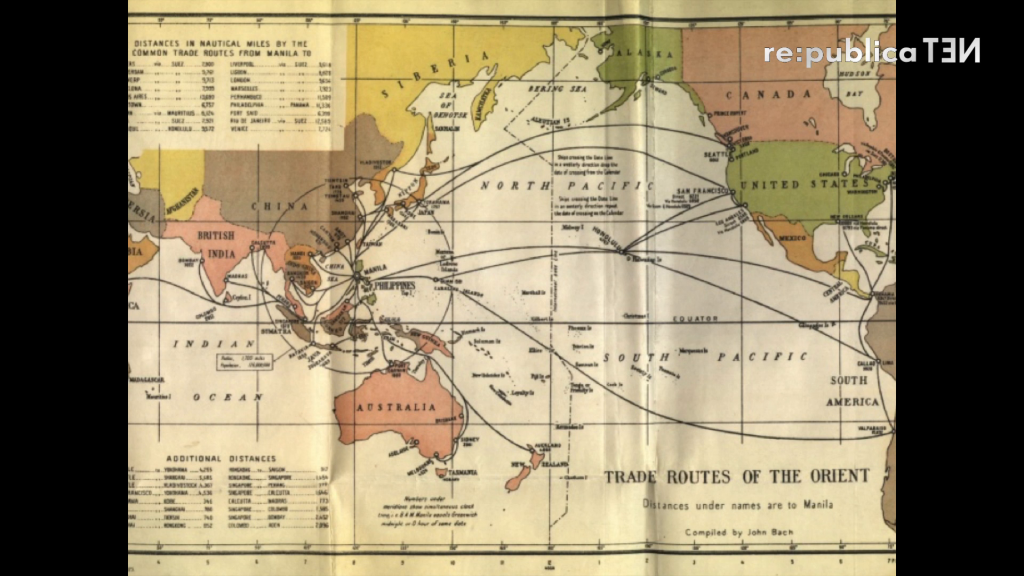

So, if we look at this 1923 map, we can see—interestingly, this is the trade routes of the Orient—we’ll see that these trade routes are actually mirrored in the way data is flowing in and out of the Philippines today. And you can see there’s a direct route right there to San Francisco. And that continues to this day.

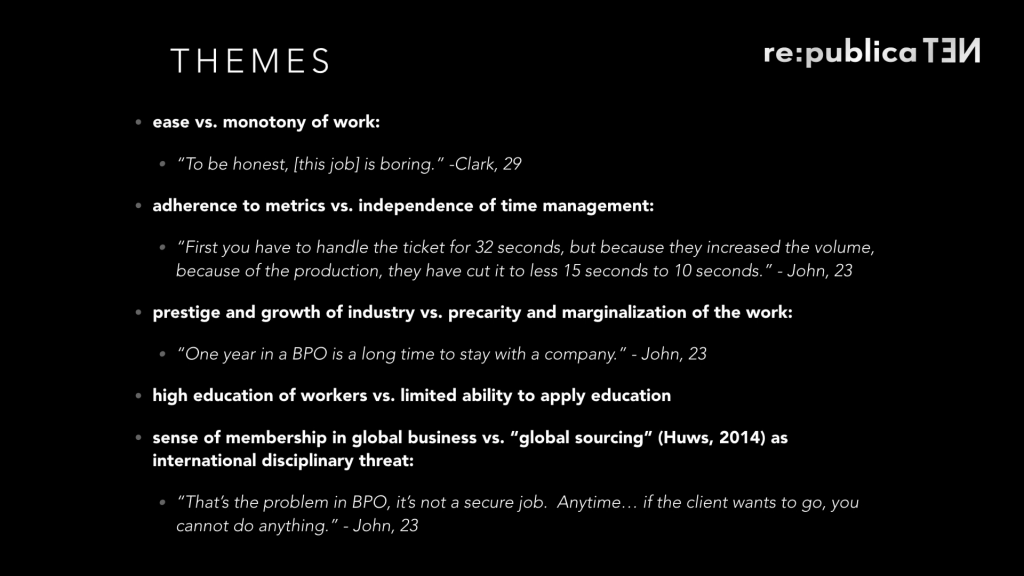

I went to the Philippines last May, and I talked to CCM workers there. We met at a T.G.I. Friday’s at 7 AM, which was happy hour for the workers there. They were meeting and drinking after their CCM shift. And they reported to me a number of themes. Again, they were very similar to their American counterparts. They were young people with university degrees looking for a good-paying job. And this is what was on offer to them, and they took it, and they took it willingly. But it had the same kinds of implications and ramifications for them. Again, no access to psychological services, and also what does it really mean if you access psychological services when your job is to be able to stomach this very content that is disturbing you, right?

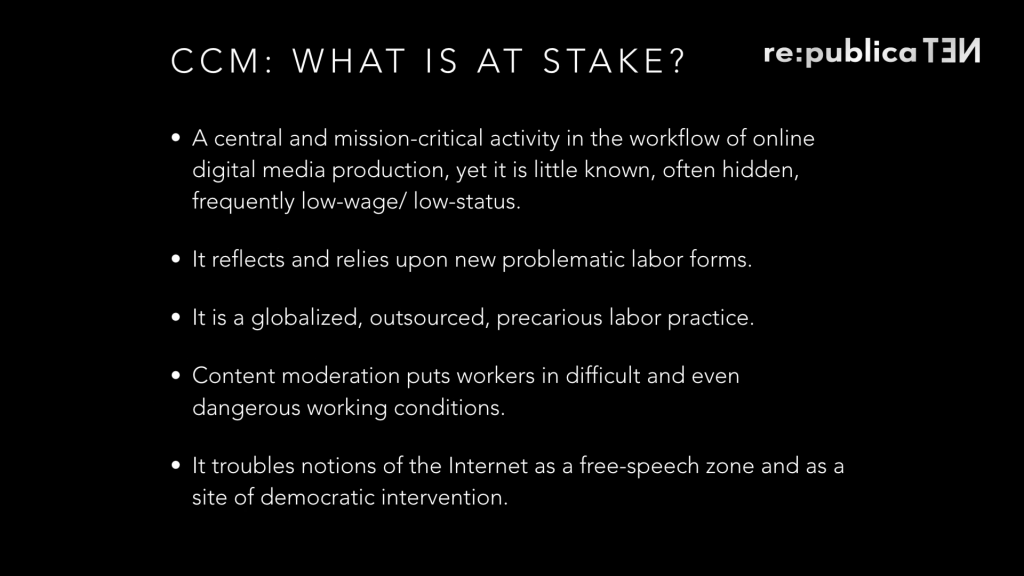

So I’m going to close just with the with a few pieces of food for thought as we go into the next talk. What is at stake when we talk about CCM? Well, certainly we’re talking about some little-known and yet mission-critical digital labor activities that go to underpin and undergird the social media platforms that we all know and use.

We’re talking about some problematic labor forms from the worker perspective. Work that can put workers into a precarious position, often with very little job security.

And finally, we’re talking about a practice that actually troubles the notion, the increasingly problematic notion, of the Internet as a free speech zone and as a site of democratic intervention. In fact, there are a whole army of people across the world making decisions about content, that people put into social media platforms, and whether it should stay or go. And they’re making those decisions largely on the basis of what will be favorable to the platform itself.

There are all these intermediaries in there. We know that CCM workers are there now. Who else is there? The NSA. We know they’re there. Surveillance is taking place. So, who else is in the mix? This is something we need to really think about if we’re going to have honest conversations about the utility of the Internet as a site of democratic intervention going forward.

And I’ll leave you with this last slide. It’s a slide in its Eastwood City itself that I took pictures of. Many people thought I was thinking it was a fine, high art piece, and they wanted to let me know it wasn’t. It was actually just junky corporate art. But in fact, I found it fascinating. You can see these are workers with headsets on. It’s a monument to Eastwood City’s BPO call center workers, many of whom are CCM workers. And the plaque on the bottom is dedicated to Eastwood City’s modern heroes. And I’ll leave it there. Thank you.

Further Reference

Sarah’s home page, The Illusion of Volition

“Commercial Content Moderation: Digital Laborers’ Dirty Work”, by Sarah T. Roberts.

This session’s page at the re:publica site.