Shannon Dosemagen: I am really happy to introduce Dr. Nettrice Gaskins. She is joining us as part of an inclusive speaker series and will be discussing techno-vernacular creativity in STEAM. For those of you who are new to the term STEAM, it’s going to be talked about a lot today. It stands for Science, Technology, Engineering, Art, and Mathematics.

Dr. Gaskins is the Boston Arts Academy STEAM Lab director, and notably the Academy is the only public high school in Boston for visual and performing arts. Dr. Gaskins earned a BFA in Computer Graphics with honors from Pratt Institute in 1992, and an MFA in Art and Technology from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in ’94. She worked for several years in K‑12 and post-secondary education,community media, and technology before enrolling at Georgia Institute of Technology, where she received a Doctorate in Digital Media in 2014.

Dr. Gaskins’ model for techno-vernacular creativity is an area of practice that investigates the characteristics of cultural art and technology made by underrepresented ethnic groups for their own entertainment and creative expression and its application in STEAM learning. Her essays are included in edited volumes such as Meet Me at the Fair: A World’s Fair Reader, Future Texts, and Afrofuturism 2.0: The Rise of Astro-Blackness, which…came out today. So look for it at your local bookstore.

I’m very happy to turn the mic over to Dr. Gaskins.

Nettrice Gaskins: Thank you.

I’m going to get started and just say good afternoon and talk a little bit about how I came to STEAM, and then what kind of work I’m doing currently.

“Techno-vernacular Creativity, Innovation & Learning” was kind of the title of my dissertation, and I’m going to talk about how it came to that and then how I found STEAM on the way, through that process.

If people are familiar with vernacular, which I’m sure you are, people in the audience outside of this room may not be. It’s basically native language or dialect of a specific population as opposed to a wider, dominant, or mainstream communication. So vernacular could be language but it could also be visual language, it can be spoken language, or other types of ways of communication.

So in 2011, I was pretty sure that there was a link between graffiti and math. I don’t know how I came to that. Actually, I was doing some interviews of graffiti artists, and listening to interviews of graffiti at the beginning of my dissertation studies, and realized that a lot of the graffiti artists I was paying attention to were talking a lot about science and math, and not making that connection. So I went to some people and said I think there’s a link between graffiti and math, and was told, “No no, there isn’t.” So my advisor said, “You’re probably right, but you need to find someone who’s done the work.”

So I made a guess and contacted Ron Eglash over at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, and he was like, “Oh. Yeah, we developed software that’s called Graffiti Grapher. It’s online. It’s free for educators.” They had a bunch of other tools that are based on cultural art, and they’re basically teaching computer programming on a very basic level and/or mathematics, or both. So these tools were just there since 2006 or whatever, and one of them was graffiti and math. And there was a lot of background about how that connected to mathematics, looking at coordinates and things like that.

But my interest in graffiti goes way back to when I was a high school student, and maybe even before that. So being able to connect it in such a way was a great thing because that’s when I heard about STEAM, around the same few months of time.

Techno-vernacular (the “techno” part being technological or technology), is sort of looking at cultural art and technology made by underrepresented ethnic groups. So indigenous, African, and Latino diasporas for their own entertainment or creative expression. So it’s less about the definition and more about how people find meaning in math. Or how they find meaning in science. How they find meaning in an art and other things. And how they sort of communicate. The look, the style, the expression that’s associated with a particular group, time, place, or event.

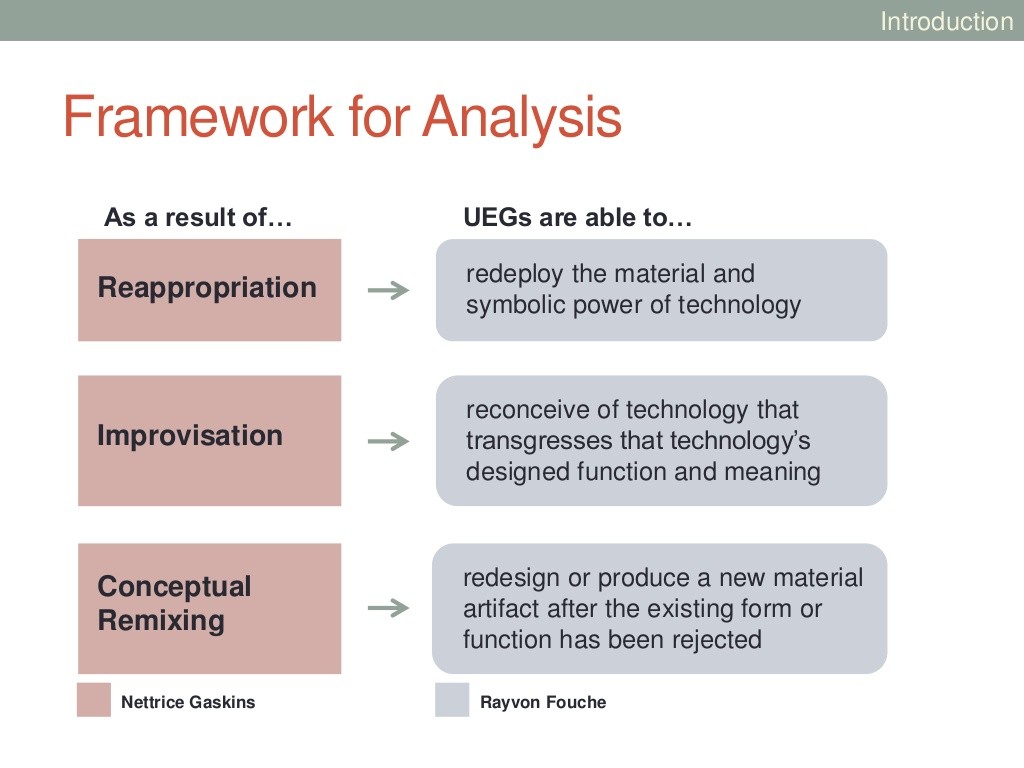

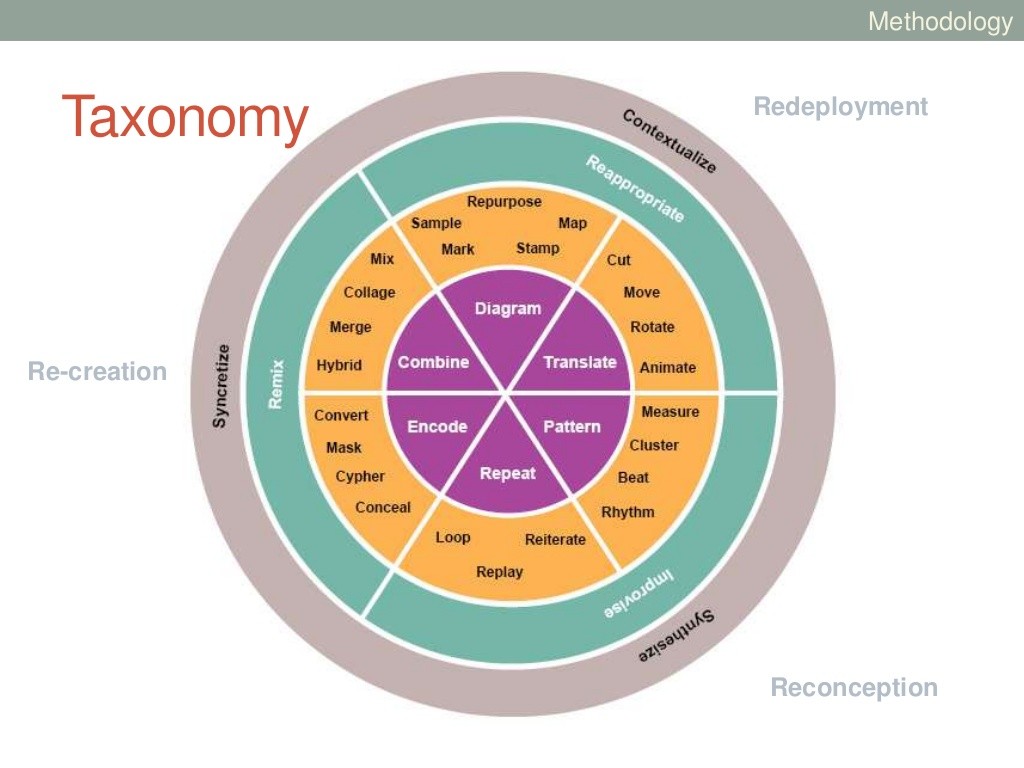

So I was like let’s look at this as a framework. Reappropriation was something I looked at, improvisation, conceptual remixing as it related to techno-vernacular creativity. And so through reappropriation you redeploy material. I’ll give some examples of that in a second. Improvisation, which is huge, is sort of reconceiving technology that transgresses the technology’s designed function and meaning. And then remixing is the redesigning or producing new material artifacts after the existing form or function has been rejected. So looking at scholars who were in science and technology studies and some in engineering, and how they were looking at these groups and how they were engaging with technology and science.

The idea of contextualizing or placing something in a new or different context, synthesizing, seeing relationships between seemingly unrelated areas and then syncretizing or inventing new things by combining elements nobody thought to put together was something that I found kept coming up when I was looking at some examples.

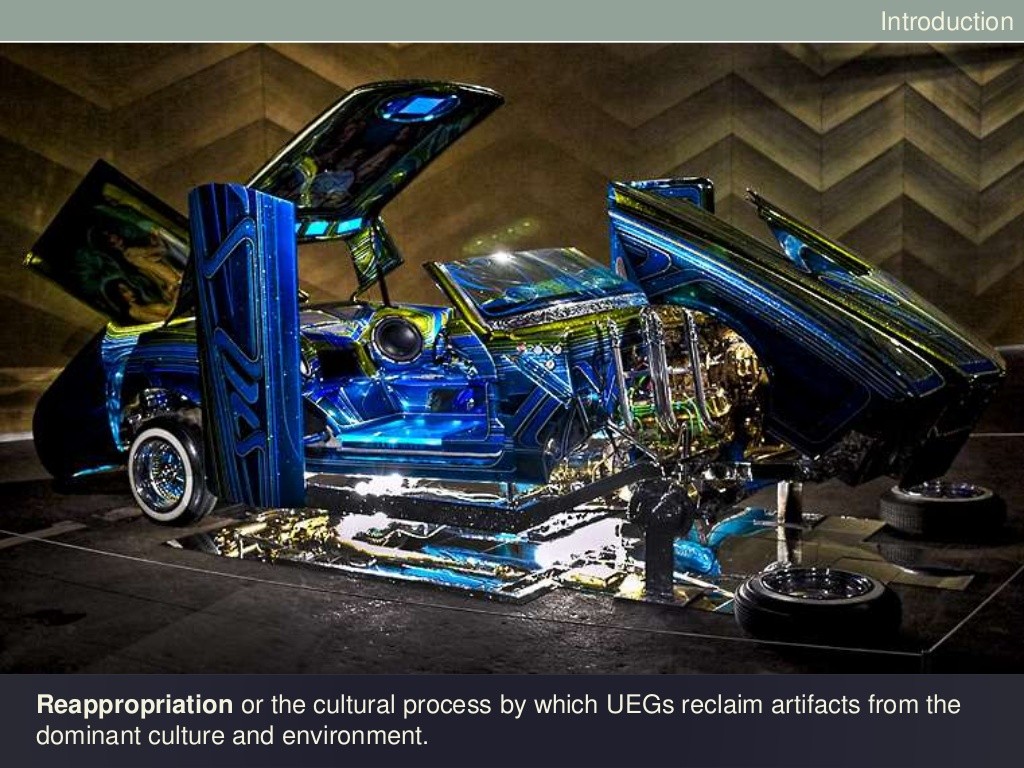

This is reappropriation. This is lowrider car culture, out of Chicano culture. There’s a film called Underwater Dreams which is about a high school group out of Arizona [who] in 2006, I believe, beat MIT at an underwater robotics competition. They were mostly Hispanic students, first generation, and beat them both in the presentation and in the actual robot itself.

But in the film, and also when I went to hear one of the people that won talk about it a year and a half ago, he started talking about hidden switches. And that is vernacular used when you’re doing lowrider cars. They used lowrider car culture to sort of get into robotics. So we talk about a vernacular, in this case lowrider cars and car culture, and then we talk about robotics. And then this is the way into robotics for a lot of groups, through this culture.

This is Kelvin Doe. He is from Sierra Leone. He was brought by MIT a few years ago. He’s also known as DJ Focus. He’s a self-taught engineer. He wanted to be a DJ, have a studio. They didn’t have the resources. So he went and found junk and put things together and created his own stuff. So in a place where there aren’t any resources, you find young people like Kelvin who are self-taught and began to do the kinds of things you might find in and engineering space or hacker space or maker space. This idea of improvising or inventing through use of materials is something that is pretty prevalent in underrepresented ethnic groups.

Then Kelvin being a DJ reminded me of this guy. This is Grandmaster Flash, who’s credited with the invention of the first crossfader, or audio mixer. He reclaimed parts from a junkyard, he began to create something now that most DJs use around the world, and is now at the Smithsonian. But once upon a time, he was a teenager in the Bronx. Didn’t have any money. And in his mother’s kitchen invented something that’s now at the Smithsonian.

This is years ago in the 1970s, and Kelvin is more recent, but we find that this happens over and over again in groups that aren’t part of a lot of discourse around science, technology, engineering, and math, but they’re doing these things anyway as part of their everyday life or their creative expression.

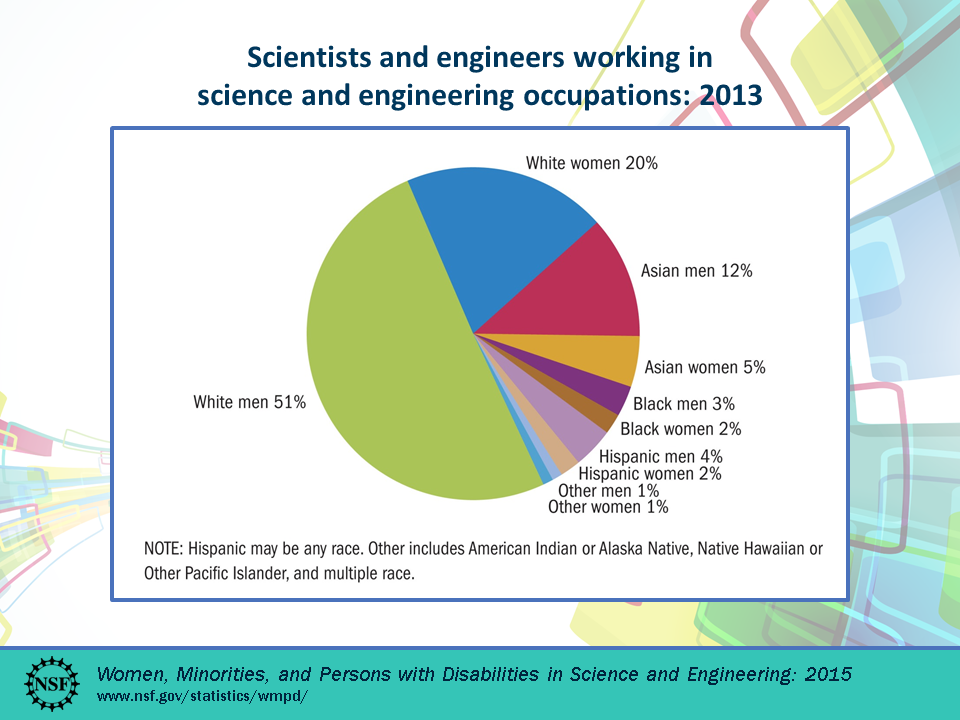

Slide via National Science Foundation, Women, Minorities, and Persons with Disabilities in Science and Engineering

I want to look at this chart. This is fairly recent, the last couple of years. This is from the National Science Foundation, and this is looking at scientists and engineers working in science and engineering occupations. The chart kind of speaks for itself. We can take a look at where some of the underrepresented ethnic groups are in terms of percentages. So, black men is 3%. Black women is 2%. Hispanic men, 4%. Hispanic women, 2%. And other would be indigenous groups and other groups. So you can see that this is their participation in science and engineering more recently. And this includes, if you go to the NSF web site in the study for this, people from those groups who actually go and major in these areas. They do not go into STEM. So it’s not just getting into STEM, but when they actually have the major they don’t go into STEM. So we look at stuff like this and then we see the kind of things that I’ve been talking about and realize that there’s a disconnect between the two things happening.

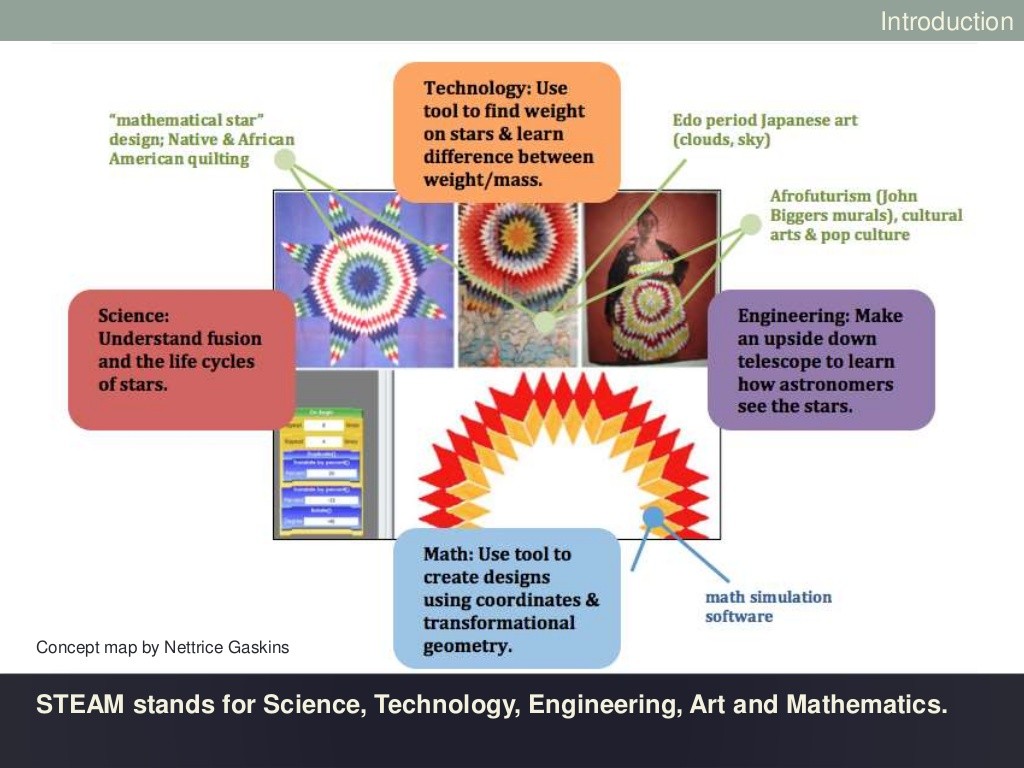

So after I started working with Ron and RPI, I started looking at his model for culturally-situated design. So connecting cultural art and standards-based STEM principles; art-based learning, which stimulates the development of 21st century skills and creativity and inquiry; and educational applications of new technologies that can be used as new openings for learning. And I started looking at how to map this into a way to develop curriculum and to make projects.

There you can see the culturally-situated design tool we were working with was very similar to MIT’s Scratch, where you are able to stack blocks and sort of create designs or simulations based on cultural art forms. So that’s math and computer science. And then also there’s meaning itself in the artwork, so the star—this is a Native American star quilt design. The mathematical star or morning star. We also have artists who look at this as a design in contemporary art and how it relates to engineering and the rest of the STEM areas. So just really trying to find ways to merge the art, show them art on an equal level with STEM.

Also, tucked away up there is afrofuturism, because a lot of the artists that I was looking at are in that sort of way of—I’ll define afrofuturism as a way of combining the past, present, and future and really sort of looking at ways in which people, the African diaspora, how they are in the future as opposed to stereotypical roles or stereotypical things that they’re plagued with in the present or in the past.

After thinking about Kelvin Doe, Grandmaster Flash. DJing, VJing, breakdancing, other types of forms that I define as techno-vernacular, I created a taxonomy to contextualize or look at how we would assess learning. So this is my taxonomy for techno-vernacular creativity. What this allowed me to do was begin to look at how this might connect to some of the STEM principles I was talking to Ron and others about. So diagramming, mapping, repeating, looping, replaying. The patterns, beats, rhythms, measure. Things that we can look at that we can say this is a domain that we can look at to assess. And then translating all that into an actual design rubric for assessment.

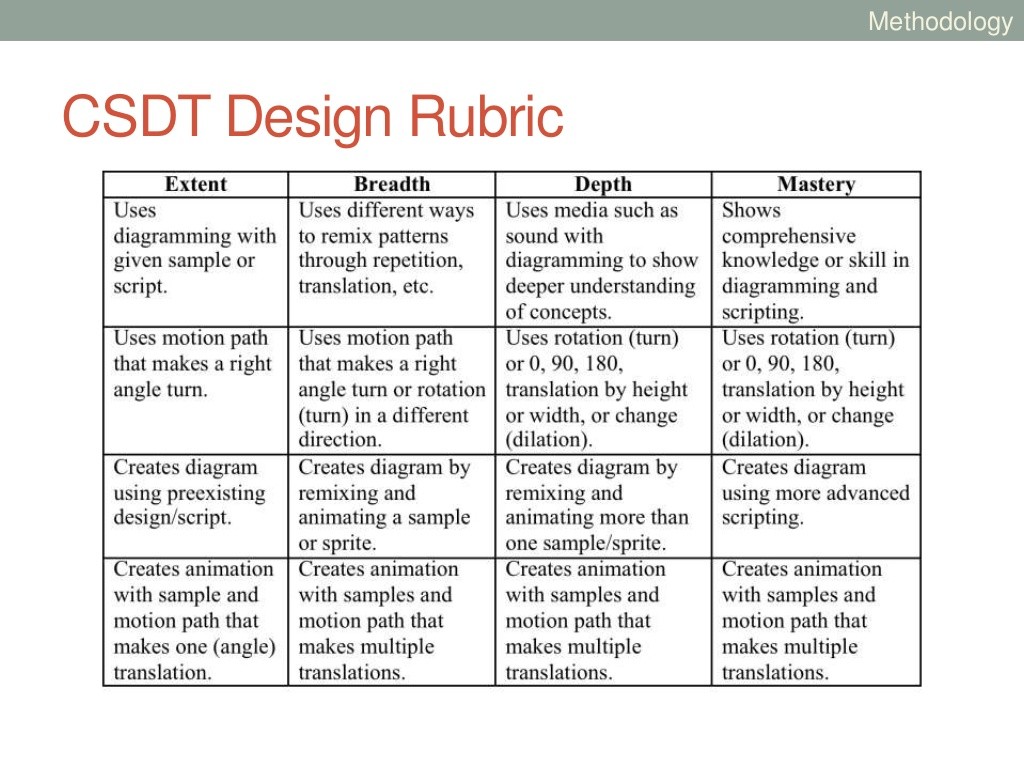

So we’re looking at diagramming, given a sample or script. And I was looking at extent, depth, breadth, and mastery as areas to assess as well. So how much did they master this? One of the things I found out is that the more mastery you have the more improvisation you have. And I’ll talk about that in a second.

Extent is designed to capture participants’ understanding of a tool. breadth is measuring changes in a number of conceptual categories an individual uses to describe a task. Depth is the conceptual understanding that they have. And mastery gauges where the participant falls along a continuum from novice to expert.

After I did all that, I did some workshops in Atlanta, because I was at Georgia Tech, and discovered by bringing in cultural art and bringing in technology, this was a way to engage young people, in this case middle school students, mostly African-American, in STEM. I assessed it, and assessed basically, without getting into all that, which I don’t have time to do, it did show that there was an increase in engagement and interest and motivation in STEM, based on the activities in these workshops that were also arts-based.

Then I got offered this job in Boston Arts Academy and I wrapped up my dissertation successfully, and started doing work here locally at Boston Arts Academy.

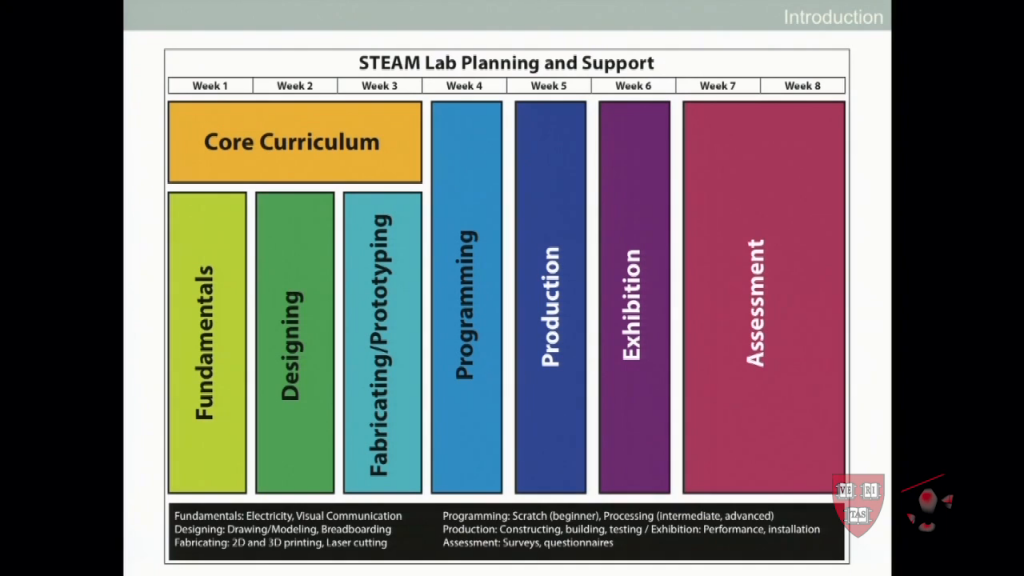

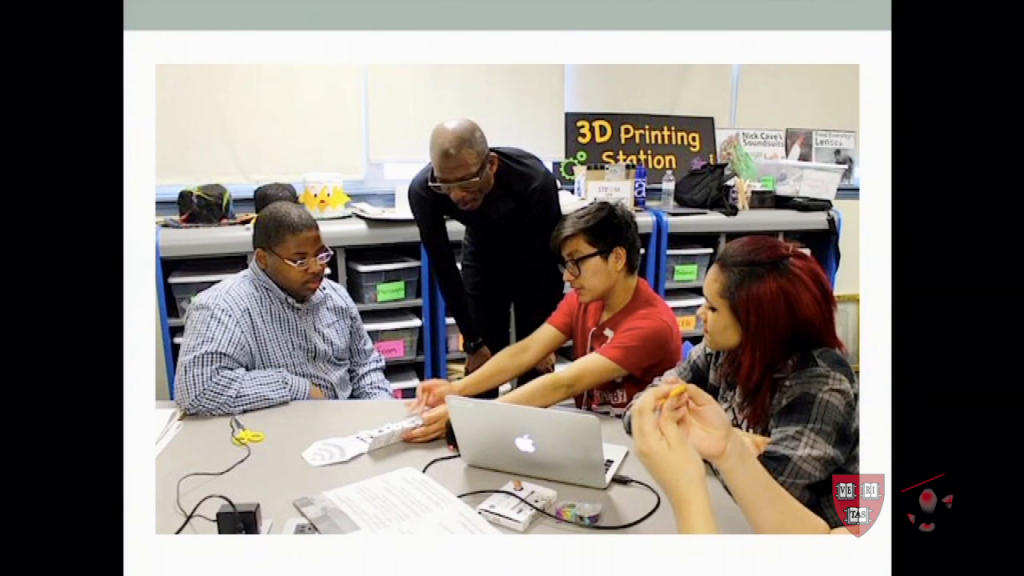

After a year, so a year and half I’ve been here, I started to think about how STEAM (I’m looking at STEAM very broadly) would happen within an arts academy, but also within a traditional Common Core or standards-based curriculum. So conducting workshops based on these kinds of modules would get us to a point where we could assess whether or not the students are more engaged, more motivated, or more interested. And Boston Arts Academy is 40% African-American, 40% Latino, and the the rest White and Asian and so on. So 80% African-American and Latino, from all different neighborhoods of Boston.

I thought about this in an eight-week situation where we talk about fundamentals, we’re talking about electricity, or visual communication, or some sort of fundamental vocabulary that young people would need to know, students would need to know. Then we talk about designing, we’re talking about fabricating, prototyping, and then programming and so on. These are artists, these are students who a lot of them are going to go into the arts. But they could also bring with them a lot of the skills that they’re learning in their STEM classes as well. So the idea of immersing them in a sort of STEAM experience is a way to help them build skills they need for their jobs or for school, and doing that in a way that isn’t separate from art at all, but that helps them work in different modalities in terms of what they’re doing. I’ll give some examples.

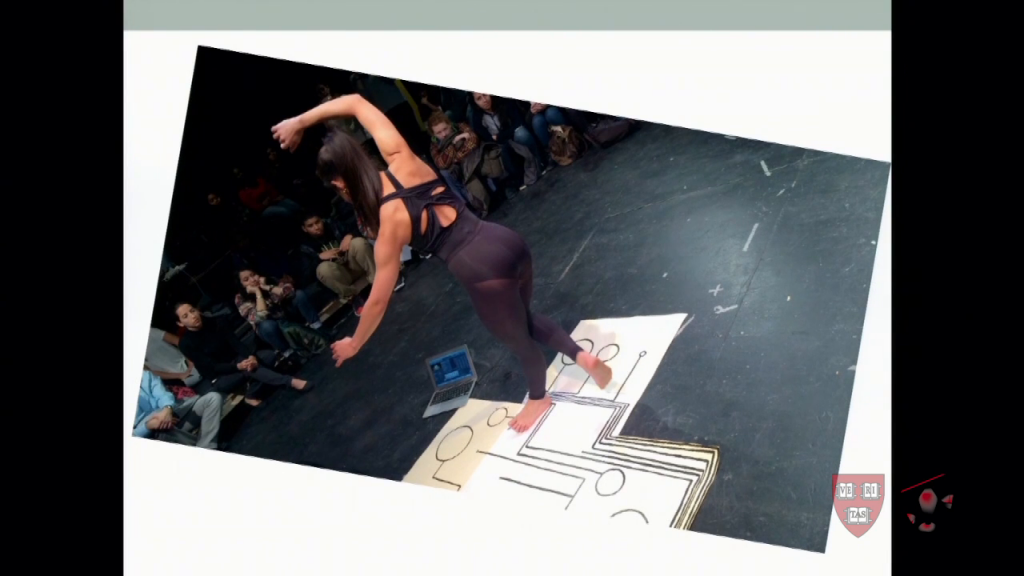

This is a dance student, and her and two other students were in a science class. They were given an extra credit project, and they came to me and said, “Oh, we like this kinda touchboard thing you showed us, this kind of small computer you showed us that makes music. So we want to know, is there a way we can make a dance floor that when we dance on it it makes music.” What you see her doing here (this is a STEAM fair at Boston Arts Academy) is her and her peers use conductive paint on paper to create a circuit that when she dances on makes music. So you can see the laptop and then there’s a touchboard on it and when she dances there’s music there. So the idea of combining art (in this case dance performance) and electronics and engineering, and a little bit of coding, is something that was early on in the STEAM lab when made it for the students.

This is using conductive paint again and touchboards, but this is a communications technology unit, part of engineering class. These are, I believe tenth graders. And that’s Hank Shocklee who is one of the architects for Public Enemy, who just got inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, who came up to meet with the students presenting their instruments that they made with conductive paint and paper and electronics to Hank, who was very much into instruments and music. This happened Spring of last year.

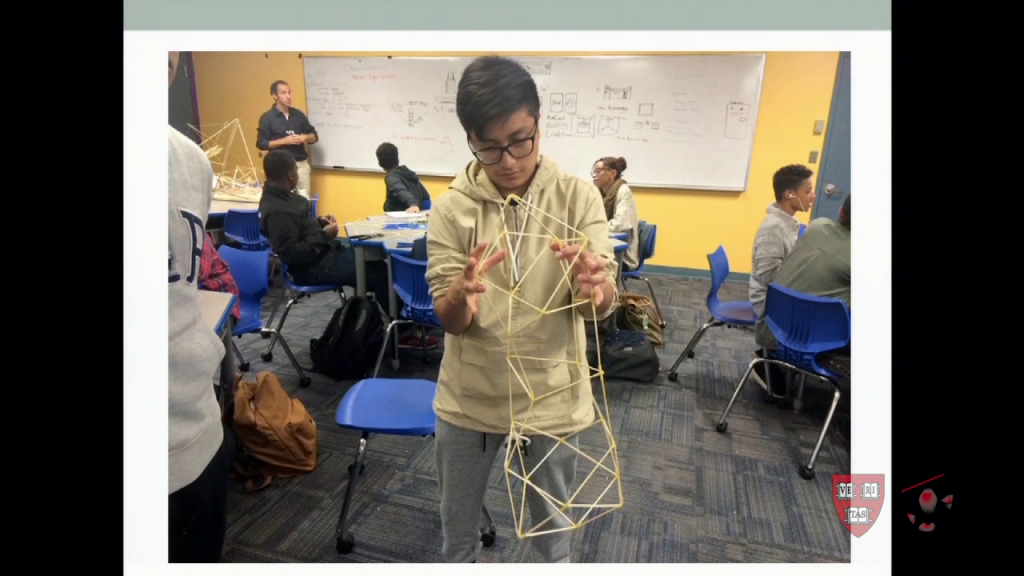

This is this past Fall, where we started looking at a concept called tensegrity, tension integrity, which is Buckmister Fuller’s concept, and how using in this case chopsticks and latex tubing they could create structures that were based on graphic and linear functions in math. They also tie this into robotics because NASA’s using a lot of this type of technology to create robots they can drop on Mars that are in the center of these structures. So here we have a math/sculpture type of mix happening. You can see the science teacher in the back and the students doing a hands-on thing in a STEAM lab.

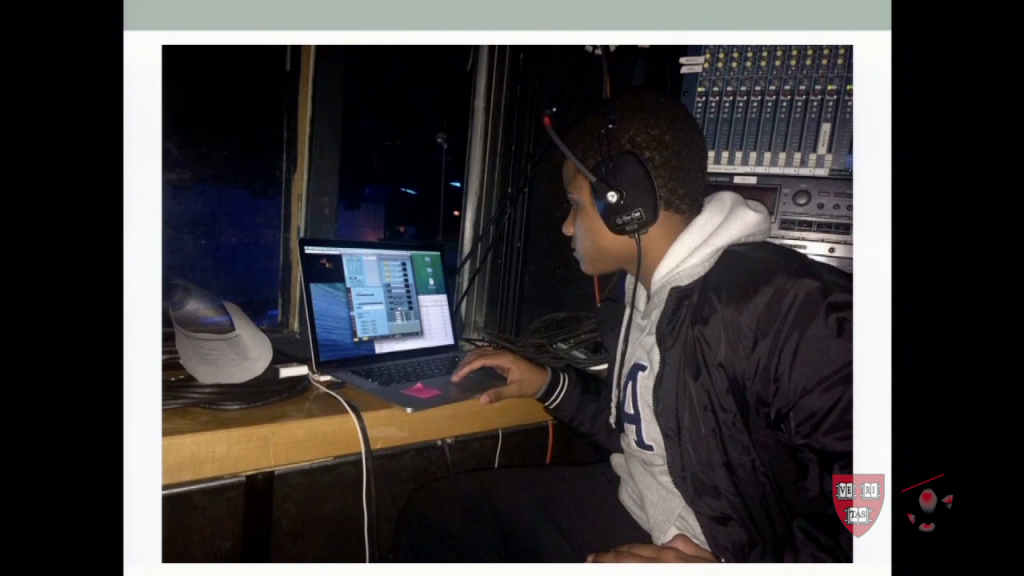

This is last week. This is in the Black Box Theatre at Boston Art Academy, and this is a student who is learning how to do video projection mapping. A video projection mapping is basically mapping multiple projections on different surfaces at the same time. So this is for a theater production that happened this past week that was basically a play that twenty-three high schools had been selected to do in the next six months, and we’re the on high school using video projection mapping, which is a computational thinking skill. We’re also using Leap Motion controllers, which are sensors based on hand movement, and using other types of technologies that we map graphically on to walls. So the student is theater, but the student’s theater plus technology plus programming plus…and so on.

So this idea of combining or working in different modalities through the arts, through science, technology, engineering, and math is something that we’re really looking to make practical for students as opposed to just within a classroom, also the world.

I could talk to other projects, but I know that people might have some questions. There are some terms maybe you’ve never heard before. Maybe you have some questions about STEAM. But I want to open it up and maybe throw it back to the moderator as well.

Audience 1: Thank you for this fascinating talk. It’s very inspiring to see the work you are doing with youth, especially minority and diverse youth. I wonder if you can talk more about the pathways and the trajectories that these young creative workers and learners are doing after being engaged in the STEAM Lab, because they’re developing all these kinds of skills, making the connections between their own culture and engineering. But how do they navigate the world after the Lab, or the world after high school, and how can they connect with job opportunities or communities in their cities or in their state?

Nettrice Gaskins: The Lab’s only a year old, so the students have only had access to it for a very short period of time. And one of the things that is very interesting—an anecdote I give about this particular student is very interesting because the student wasn’t doing well academically. But he’s very good at video games, and very passionate about video games. As it turns out, video projection mapping is very similar to the kind of games he plays on PlayStation 4, where he has multiple screens up at the same time, with other players. So the idea of working within that kind of modality is something for this particular student, he’s already doing every day, or would like to do every day.

The idea that you can tie in programming or tie it into a theater context is adding a layer of meaning and skills that that student may never have anticipated until last week. And as a result of this a‑ha moment, he will now be able, along with other students, to incorporate this into what they’re doing in theater production. And of course, he’s sort of in the same modality that he usually is in with video game playing.

Now, later on since he’s a sophomore, he can begin looking at more specific skills that will help him advance this type of interest. So if he wanted to go into more of a computer programming aspect of theater production, he could do that. If he wanted more on this idea of multiple screens and working with a programmer, he would be able to do that and have that skill set already.

But it really is kind of, now we see where these kids are coming in and where they connect. Then we can begin to make this more real and more practical for them as we go along. So the dancer who wants to use conductive paint and use electronics to enhance their dance performance. They may not do that every single time, or they may do this in particular ways, but the idea that they now have these tools enables them to be able to take it to the next level when they’re ready. So, I don’t know if that answered your question but, for now.

Audience 2: I’m just curious. To facilitate these kids’ transition to tertiary education and to jobs, which is the question that was just posed, have you considered a program of internships where they could develop these skills supported by creative people, older creative people in the arts?

Gaskins: There’s already internship programs in place. There’s summer programming as well. So I think, we have a lot of video game design companies in Cambridge, so I’m sure there’s opportunities to engage on that level as well.

And one of the things I wanted to say is not that these young people aren’t interested in these activities, it’s that they don’t see themselves or see people like them doing it. The reason why I am comfortable programming is because my mother was a computer programmer. I didn’t like computer programming until my senior year of high school. So I actually didn’t do any programming until much later in my teen years, partly because my art teacher decided to teach computer graphics and convince me after several attempts to get me to take her first computer graphics class, which then led to me majoring in computer graphics in college.

It’s a very short period of turnaround time, when you think about it. So I’m a junior in high school in visual arts, and then majoring in computer graphics a year and a half later. There’s a portfolio you have to make, so there’s a lot of work the teacher and the students have to go through. The opportunities that the teacher hoped would happen, she wasn’t entirely sure what would happen when we began. So competitions began to happen and the National Science Foundation actually had a competition for art and science back then, and my computer graphics work won a prize.

These were all incentives to continue in that direction. I did not anticipate that I would go into computer programming until I got to Pratt and then I felt like they had kind of snuck that in on me. So this is the stuff my mother does, not me, I’m an artist. But then I have to do this as part of the requirement for the major. So a lot of this is building a blueprint as you go along. You have to first figure out what it is, what modalities young people are comfortable in, and what they feel they’re passionate about. What is not just culturally relevant or responsive, but what is personally relevant and responsive. What makes sense to them and what they do in their day to day.

Then you connect that to the world that’s foreign to them, that’s outside, that’s mainstream and dominant, where they’re not reflected. And I think then you begin to sort of hash out the kinds of activities outside of school that they can get involved in. They might be entrepreneurial, or they might be within an existing business or company.

Audience 3: I don’t have a question, but I have a recommendation. I know you’re interested in afrofuturism and space and science fiction. There’s a program at MIT for students. It’s part of the AeroAstro department. It’s called Zero Robotics, where the kids have to learn how to program, and they upload their code to the International Space Station. And we watched during the finals, the astronauts while they’re not flipping around and having fun, they have to use these actual artistic SPHERES (that’s the acronym) to have competitions. There are like nine states, and I think they’re doing it overseas as well. And it’s great to see Texas vs. Florida, DC/Maryland vs. Massachusetts. But it’s an artistic representation of their code. So you might want to get your kids involved in that. I’d be happy to let you know.

Gaskins: Thanks for reminding me. We actually met with the new Deputy Director at NASA. About a month ago we had lunch. Me and one of my students had lunch with her and her assistant. We talked about some of the things in terms of their Journey to Mars project. Obama earlier this year decided that by 2036, people will actually be on Mars, as opposed to driving by Mars, or getting close to Mars, or dropping robots on Mars. So this is a new initiative and Dava Newman was here, and she did her lecture at the Museum of Fine Arts. Then we had this lunch and I started talking about ideas that I was having.

Then I found out, as it relates to the arts part, that the Voyager 1 space probe gathers data on plasma waves and then they have been converting that to music, or to sounds. So we have students who compose music. So what happens when we begin layering in data from the plasma wave probe that could actually get them involved with this Journey to Mars project. And then my student has his own vision of an interface that’s not based on touch but based on proximity and projection. But he was able to pitch to the Deputy Director of NASA, and folks. So this idea of a visual arts student being able to do that was a great opportunity for him and for us as well.

Audience 4: The stories are really interesting. I like seeing the connections. How do we scale this? Are there programs that you can drop into a school or to train a teacher? What do we do to have this reach more people, not just the best, but the average who have these interests and are making these connections?

Gaskins: I think that in addition to initiatives like Journey to Mars, there needs to be more of a focus on computational thinking and teacher training prior to them hitting the classroom, and then also as professional development. I think it’s a modality, it’s a way of engaging with material. And I think it also helps—it leads to computer programming, of course. But it also leads into some of these other things such as conductive paint and touchboards and coding. But I think it also is a way of thinking about how you structure activities as well. Some of the STEAM programs I’ve been reading about have really focused on computational thinking, and I think we need to just sort of say what that is and then create something that is able to go into an educational place and train teachers on. But it doesn’t exist yet in a lot of programs for preparing teachers for schools.

I think that’s a first step. I also think the cultural piece is missing. So I think the part that engages students that are from underrepresented ethnic groups is missing. I think they don’t see themselves reflected, don’t see their interests or their cultures reflected, so they stay outside of it even if it’s free, or even if it’s something that is in their neighborhood. It just is a harder sell for a lot of young people who just can’t see themselves in STEM or STEAM. So beginning to incorporate those types of modalities and experiences and making it responsive to culture, responsive to interest, is another step that needs to happen more in a broader fashion.

Audience 5: Sort of as a follow-up to that question, can you talk a little bit more about how the program animates across the curriculum at Boston Arts Academy? Is it a discrete course that students are taking or a sort of drop-in lab? Is it a resource for teachers or is it sort of all of the above? So how does it work?

Gaskins: All of the above. So you have the tensegrity situation with math classes. So math classes came down, tenth graders, and did a tensegrity activity with an artist. But obviously you could take that into different directions, if you’d like, including science. Also, the idea of thinking and working in different modalities for people who don’t do that is a challenge. If you’re a science teacher and science is your expertise, and you’ve never made art and art is not your expertise, it’s really hard when you’re planning to figure out how to incorporate that, or how to incorporate computational thinking and coding and programming. And the same for math, and even for art. If you’re an art person and haven’t really thought about deep engagement in science— So, we do have art science activities happening at Boston Arts Academy where scientists are working with artists, and they’re working with young people in the classroom. So sometimes that one person, it may be multiple people. So you have an artist and a scientist willing to work together, or work across disciplines in order for that to happen.

Audience 6: Thank you so much for the talk. I guess I was curious about…well, first of all thank you for the fact that you’re giving language to things that are already going on in communities. So like with the hidden switches that are going on in Latino communities, or whatever the case may be. So I was curious did you run into roadblocks as you developed your taxonomy, as you were thinking about how does the vernacular translate into what academia already accepts or says is the terminology for technological innovation or that space?

Gaskins: One of the things that I noticed, being African-American and female in a predominantly White institution in Georgia Tech in terms of faculty, is I noticed that the curriculum or canon didn’t have anyone of color in it for digital media. It had a few women, maybe three or four, five, for a two year span of reading. And then no one of color. So for someone who really wanted to do something that was culturally responsive, that presented a problem. I had to find a Ron Eglash to really kick that off. Someone who was an ethnomathematician who studies cultures and who connects it to math.

But I also had this knowledge of being an artist and working with graffiti artists, working with regular contemporary artists, making art myself, and my interest in science or my interest in technology, obviously was something that really pushed me to think about how I would describe the types of projects and works that people in these communities were doing that made sense in a STEM or STEAM capacity. So creating a taxonomy, a domain, saying this is a domain, was my first… And then how do you create a framework around that conceptually and theoretically was the other piece. So before I get to the actual STEAM Lab, I had to create this framework which to work from, because it didn’t exist. So that was problematic.

But then once you do that, it starts moving, and you start realizing there’s this whole world of innovation happening that is not often making it to academic discourse. But when it does, it’s this a‑ha moment or we bring a kid in from Sierra Leone and we study that, realizing that this happens a lot, just in many other neighborhoods around the world including in the United States, where people don’t have resources and because of that are innovating and creating in their communities. So the taxonomy and framework was the basis, but then getting into it and making and doing was the next step.

Audience 7: Your earlier slides with your taxonomy got me bubbling about the cultural bricolage you describe. And I think you may have just answered this a little bit now, but most of your examples have been students who have an artistic bent by nature, and they’re by virtue of this program’s efforts being like, “Ohhh…,” opening their minds to the possibilities that the science/technology/engineering aspect STEAM represents. But I’m very much hearing you say that you and your program sort of occupy this bridge-building middle ground, and I’m wondering how much either of an effort you’re making or examples you might have of someone who’s a science/technologist/engineer by bent is saying, “Oh,” and having their mind opened to the artistic possibilities of the other stuff they’re doing. I ask because I have some friends working on doing that same kind of bridge-building building with respect to empathy and ethics and policymaking saying, “There’s this whole other stuff you need to think about and will make you better at what you do.”

Gaskins: I think that legislation just passed two months ago for STEAM, so that means more support from the federal level. But also, when I talk to artists about science, they’re interested. “Huh. I do that all the time.” Or math, “I create choreography based on fractals.” Happens. Artists are very open to those kinds of connections. But if you talk to, not an ethnomathematician, just a mathematician, they may not get it. They may not even see it. Ron will tell you, “I appreciate low art. Not an artist. I refer to people who know that to work with when I do these projects.”

But at the same time, every once in a while you’ll find a physicist or some sort of scientist who has some arts background or has some sort of appreciation for the arts. That’s the person you start to work with. Then at some point colleagues begin to appreciate the connection. But I think that has to happen more often. It’s very difficult; it can take years just for that to actually happen. So we do have an arts science type of program spearheaded by TERC at Boston Arts Academy right now. The focus is the microbiome, so teachers and artists are working with scientists from The Broad Institute on how to bridge art and science. It’s a three-year funded project and they’re going into the third year now, but they’ve had some understandings about how difficult the process is to bring people from different disciplines, different areas and fields of study together and how do you get everyone on the same page in order for them to begin to work on things that benefit young people, benefit students and communities. So, it’s a process is what I’m saying. It’s not something that may happen right away.

Audience 8: Hi. Thank you for this talk. This program has been up and running for a year. Where do you hope it’ll be in five years and what sort of steps do you see in the future both to scale it and to make it broader and deeper?

Gaskins: I think creating structures within formal settings that enable inter-disciplinary collaboration is a step. I think it’s a big step. So we’re not just in the science or math team, we’re working in our team with members of other teams, and we’re working on projects where it makes sense. So it’s not forced, it’s something that comes naturally and people have buy-in and are committed to it. And it’s a struggle because a lot of art teachers don’t have to face standardized testing, for example, the way a science or math teacher would. So the kinds of pressures that are on science and math teachers in school will help create a challenge for them to be able to say, “Okay, I’m going to work on this piece for the arts,” unless they understand how the arts benefits the scientific piece, which I think it does. But it takes someone who understands both of those modalities to make it very explicit and clear. So finding the people who understand that is a challenge as well. And those are the people that can help guide folks who may not understand how to connect to the arts, who are in science or math, or technology, or art the other way around.

So I think in five years I would hope to see, because of all the STEAM initiatives— And I also want to point out that another educator in a half-day workshop on STEAM had asked the two science teachers who were talking about maker spaces where their art was. And that was interesting because they saw maker spaces as engineering. And the kinds of fundamentals that you’re getting out of maker spaces, primarily, don’t happen in the art studio; it’s different. It’s a different habit of mind. So what happens when you mix these habits of mind and working in practices together, but not to assume that [?] you have a fab lab or a maker space that you’re doing art. But you have to think about what is artistic about what we do in a maker space that we can make more explicit to people who are really interested in the arts.

So there’s lots of different conversations that need to be had, and ways in which we can collaborate that need to happen in three to five years in order for us to begin to make some inroads in this field or domain.

Audience 9: Hi, thanks for your talk. It’s very inspiring. I was wondering if you could say a bit more about how this could be scaled up and how you see yourself potentially participating in that beyond the school that you’re at. And if you could also just throw in a little information about that legislation that was passed a couple of months ago.

Gaskins: Yeah, I forget the name of the Congressperson, but it’s been on the books for a minute. But if you do, STEAM legislation, it should pop right up in a Google search, because it just happened.

Audience 9: Does it have funding attached to it?

Gaskins: It will, because what happens is when you say that this is an actual thing we are interested in funding, on a federal level then you begin to create a line item for it, as opposed to not having it there. Because usually people know about STEM but they don’t know about STEAM. Now there’s this knowledge about that. So one of the things I do is I create things in modules. So the taxonomy’s in modules, this [STEAM Lab Planning and Support slide] is based on modules. When you talk about scaling things up, you have to modularize it and then just like in Scratch or Tetris or whatever you have to be able to plug it in in places where it makes sense sense. But you have to make those modules and then you have to make them be able to connect to other things. So I kind of take a Scratch or computer science approach to an art curriculum development because I feel like there’s a lot of room for development in how we create these and how we put it together. How we build it may change according to the different environments we’re in. So what I do at Boston Arts Academy is going to be different than what a Philly school does, or different from Natick or some other school or program. But there will be elements that everyone can agree upon that need to be part of the program, part of the planning.

Audience 9: Are you able to connect with like-minded colleagues across the state and the nation?

Gaskins: I came into Boston with those connections already. So, as part of my PhD work and being sponsored by the National Science Foundation, I was connected to networks that are already kind of STEAM-based. So I did some work with the Smithsonian, I advocated on Capitol Hill for NSF and learned how to be a lobbyist, in a sense, and understand how funding works in Capitol Hill and how to talk to someone about STEAM who may not have that knowledge or appreciation. And also there are networks of academics and folks in education who are doing academic papers and things like that who are sort of the decision-makers in some of these programs that get funded. So being part of those convenings has been something that’s been part of my work as well.

Audience 10: How does your thinking, your approach, related to the Emilia Romagna approach to early education? This is Northern Italy. Basically, they teach the three Rs to very young kids, pre-schoolers, early schoolers, where they teach the three Rs through building projects and art projects. (I can’t make a distinction between the two.) There was even a school, I don’t know if it’s still the King’s[?] School in Cambridge used that approach when my kids were primary school age. I know because I visited the classroom at one point. So have you looked into that? I don’t know how much theory there is about the Emilia Romagna approach. I’ve seen it in action, but I don’t know the theory myself. But it’s basically what you’re doing, but it starts with very young kids. And it’s not an option, it’s just the way they teach.

Gaskins: Actually, I think that the idea of us figuring out where we’re going or where we are in education and where we could go and what other people are doing successfully is something that needs to happen as well. But I also think what happens within a particular community or group could happen differently in another community or group. So it’s really based on the interests or the everyday practices of the groups and where they are.

Audience 10: You probably said but I didn’t catch how old the youngest kids are when they come into the program.

Gaskins: At Boston Arts Academy? They are ninth graders, so thirteen years old. And there can be an argument for things like computational thinking and programming should happen younger, so that they have time to be in that modality before they get to high school, and I would agree with that. But also, when they don’t, then we have to sort of meet them where they are. So I think the idea of working elementary and middle school, much younger ages, I think really prepares them. My exposure to computer graphics and computer programming came from my mother, even though I didn’t engage that skill or get into that until much later in my youth. But having that exposure and knowing that my mother could be a computer programmer meant that I knew I could do that, too. So I saw someone, it was reflected in someone I knew and that was close to me. A lot of these kids don’t have that at all. So I think the exposure, access, opportunity, but also exposure to people who are from their community or from their neighborhood or whatever doing this type of work is also a motivator to stay with these types of dominant, mainstream types of things that we’re not involved in.

Audience 11: This may sound like heresy, but I believe that if a lot more math and science teaching took place in this sort of context where it’s actually connected to the things that you use it for, that we would have a much more educated population by the time they finish whatever study, or in fact they would never finish. Because currently the math and science that we teach is often so detached from where it came from and what it’s used for that this is one of the reasons why so many people are walking around who have been turned off by their school education. Comments?

Gaskins: In my case, I always knew I was going to be an artist. That was actually my mother’s doing. I knew from a very young age that art was going to be it, but I like science. And I did really well with technology. So there were things that were also fostered and pushed forward, but my mother’s not an artist. She doesn’t understand the arts, maybe has an appreciation for it. And I think that her training, her education, was devoid of that. And I think a lot of folks today are also devoid of that in their education. So the appreciation may be there, or maybe not at all. So that needs to be cultivated in the educational process, meaning academia or… So as an undergraduate or graduate, you actually have some inter-disciplinary connections, otherwise you’re not really going to know where to connect, or how to connect, without professional development. It creates a challenge, but I think it’s a challenge that we can meet because we do have this idea of a STEAM education and now there’s legislation and all this interest in it.

It’s also international. So there are people coming from Colombia and other countries who are doing STEAM initiatives as well. So I think in terms of we’re in a moment. I talk about afrofuturism a lot, and when I talk about afrofuturism, I talk about it from the standpoint of someone who’s used to virtual digital spaces, who not just works in visual arts but also works in coding and programming and how do I create different types of artwork that are afrofuturistic using code. That kind of language isn’t talked about a lot. We talk about speculative fiction, we talk about writing. But see writing also as coding. But that’s me and my interests. So the more we have exposure of folks, we have writers, we have folks who are artists, who are doing coding for creative expression, for example, then we are able to bridge that and get it to a point where we can give access and opportunities to young people who need it the most.

Audience 12: I have just a couple of comments and stuff, and then a question. I love that we’re just starting off the conversation as STEAM and not how to get the A back into STEM, which is where in the arts education space, that’s been a lot of what the conversation I feel like has been focused around for the past several years. So I just love that that’s just initially where we’re just starting the conversation.

I also love you bringing in things like the tensegrity sculptures and stuff, and bringing in Buckminster Fuller, who’s a great example of this blending of art and technology and design and all that sort of stuff and came out the Black Mountain School which also spawned a number of other of this sort of thinking.

So my question, though, is are we just talking about something else other than just the traditional academy of departments? There’s the mathematics department, there is the arts department, there is the science department. How do we actually get past that sort of rigor that’s already been established within education, to bring in this more inter-disciplinary thing? Is it that the easier wins are injecting more art into math, or injecting more math into art? Which direction do you see the bigger wins and the easier ways to make this more successful in creating an inter-disciplinary structure?

Gaskins: My fear about STEAM is that arts were not on the same level, that they were just an addition as opposed to actual deep engagement in the arts. I also think that deep engagement in the arts means that you have someone who’s used to being in that sort of space as part of the conversation. So if you’re not planning with someone who is an artist, who is used to that experience, then you’re going to be missing out. And also I find that sometimes when you’re talking about STEAM and you’re talking about math, for example, you’re really talking about fun math, not art and math. Which is great. I think it’s great. But it’s not deep engagement in the arts. So I think some people, science or math teachers, may say, “Oh, this is art,” when it’s not. It’s fun. And I think the association between art and fun…sure, but now we’re talking about something that’s not really STEAM.

So I think we have an opportunity to begin to look at the kinds of ways we can— And sure we can bring in humanities, writing, we can bring those things in. But I think it still is the same challenge. It’s how do we find a common language? So, when I did get funded by the National Science Foundation, I brought in an astrophysicist, a mathematician, and an artist, a Native American artist, African-American artist into the room to talk about what’s our common language. How do we begin to work together and understand each other, even though we come from different ways of working, ways of creating? And I think that’s a first step. And I think the more we do that and the more convenings we have that do that, then we start getting to what you were talking about in terms of it’s not just art added, we’re talking about more of a sort of inter-disciplinary space or experimental space for learning this kind of stuff. But right now we have to create those spaces and we have to create those opportunities for these folks to come together where they feel like they belong or feel like they have a voice.

Audience 13: Just kind of showing my ignorance, I was just curious if a student loves your program and they graduate, are there higher education programs that would be prepared to engage them and let them continue with this kind of thing? Are they few and far between or…what is the landscape?

Gaskins: I think higher ed, there are lot of other challenges beside that, such as finances, that I think are real prohibitive for students who don’t have those resources. Once you’re into a program, you might find some pockets of that kind of work happening. But first you’ve got to have the money or the resources to be able to get there. And a lot of the young people are going to be faced with a lot of debt and a lot of problems of even getting to that point, which is getting worse by the day. But at the same time, I think having a sort of entrepreneurial spirit helps to boost motivation to go in that direction but now you build that blueprint, you build the resources, as you go along and you have what you didn’t have before going into the program so maybe you don’t have as much debt. And maybe you do have a little side business, or maybe you are collaborating in a little production company with your friends and you’re doing this kind of inter-disciplinary work and having your own game company or things like that. And some young people do that, and that’s how they get through. But a lot of the young people that I’m talking about don’t do that yet. And I think that is something that needs to happen more, where we provide the spaces but also provide the opportunities for these types of collaborations and incubators, where they’re actually creating the blueprint and then the financial structure to be able to do these kinds of things that are a little more hard to do like going to school after twelfth grade.

Shannon Dosemagen: Some of us are in a working group at Berkman, the Inclusive Innovation Working Group. We talk a lot about different technology projects for civic engagement and civic participation. And I’m wonder, from what you have here around program design, if you have thoughts on the underpinnings or the underlying ideas that really help students work through the process. So one might be holding up failures and talking about failures openly rather than pushing them aside. So I would to hear if you have thoughts on that, just from the last year that you’ve been working on this.

Gaskins: Saturday, we did five performances in the theater using the video projection mapping. We had one particular student who was very good at it, and then the program glitched during a performance. So I’m pulled from the audience when the student is panicking because…it’s not a full failure, but for him it was because it’s not doing what it’s supposed to do. So I said it’s working to some degree, so let it roll to intermission, and then I’ll come up and fix the issue. And that’s kind of how it is. That’s what happens when you work with new technology. My behavior…I didn’t panic…you know, the student was panicking. We have to get used to the fact that it doesn’t always work, and we have to make it work in the best way we can and then keep moving. And I think this idea has been modeled by the adults who are in the young person’s life, the teachers, the artists. And I think that failure, the more times you— It’s not that you fail all the time, you fail and learn. But you have to fail, because you can’t really succeed until you realize where…areas that you don’t go into. But I think that a lot of kids have been sort of indoctrinated in this idea that if you fail you’re a failure. And I think that has to change. I think these types of projects will require students to get used to the idea that it’s not always going to work. And the behavior of just tossing a project and saying, “I can’t do it,” or, “It’s not going to happen,” is not how you get to completion. And so I think seeing folks, adults, artists, who are doing that, who are failing, getting up and figuring out, going in and fixing it and rolling with it, I think is a good lesson and I think helps young people’s understanding that it’s part of the process.

Dosemagen: Do we have last questions? Alright, then. Thank you very much, Dr. Gaskins. I think it’s been a wonderful session.

Further Reference

Event page at the Berkman Center web site.

There are many posts at Dr. Gaskins’ blog on both the techno-vernacular and STEAM.

Techno-Vernacular Creativity, Innovation & Learning in Underrepresented Ethnic Communities of Practice at SlideShare, the slides for Dr. Gaskins’ dissertation defense. These predate this presentation, but contain the majority of those visible in the video and many extra.