How do you see your work differently in the context of the full group presentation? Where has it taken you?

Archive (Page 1 of 3)

Golan Levin: Welcome back everyone. So for the last few minutes here we’re going to have a group discussion Q&A moderated by professor of Games Learning at the Parsons School of Design John Sharp. Come on in, John. And come on in everyone else, too. I’m gonna pop out. John Sharp: Thank you, Golan. Thank you everybody …read the full transcript.

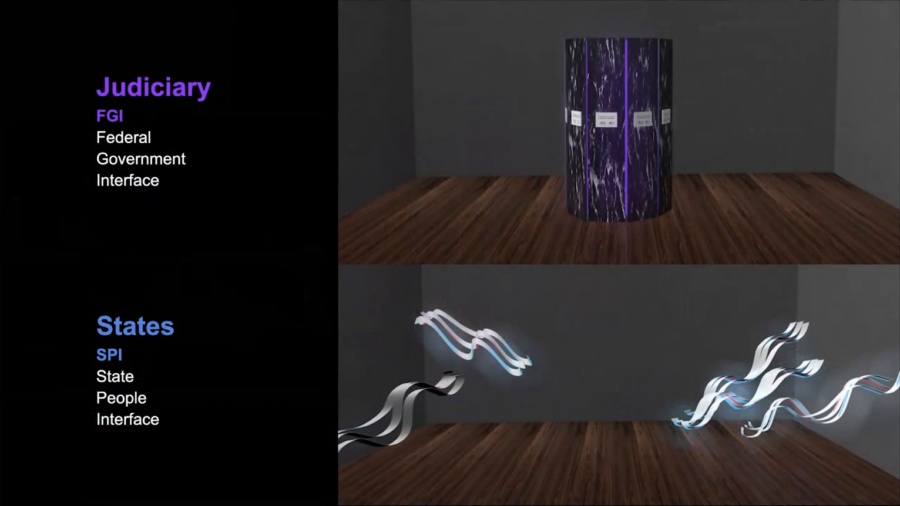

When we were developing the concept for v.erses, we were particularly struck by the final clause of the Tenth Amendment, which reads “are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.” This unambiguously reserved all non-delegated power to its original source, the people.

The question for me is, how do you know your rights? Where does your mind go when it gets a hold of those rights? The Ninth is saying there’s a written space here on this piece of paper, and there’s an unwritten space somewhere beyond.

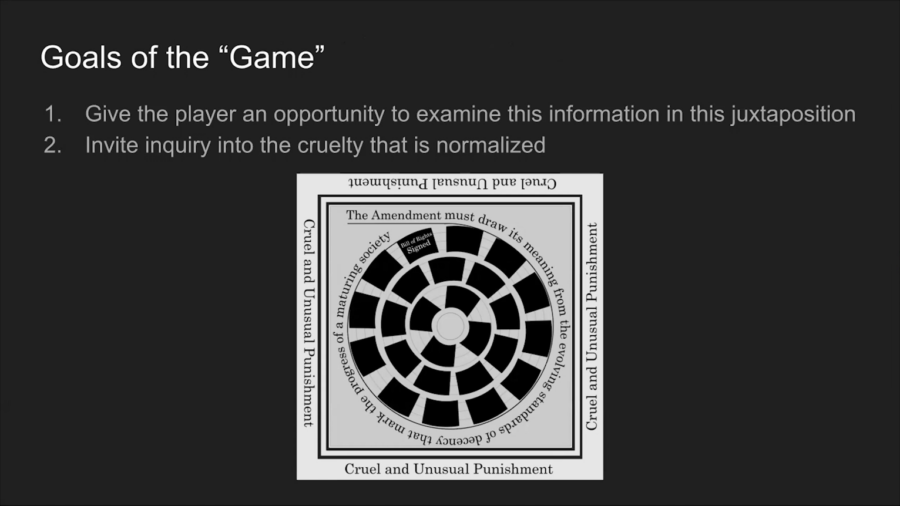

Justice is so often envisioned by the metaphor of scales and balance. I’m making a gimbaled marble labyrinth. The gimbal allows for balance, but it is set by the user.

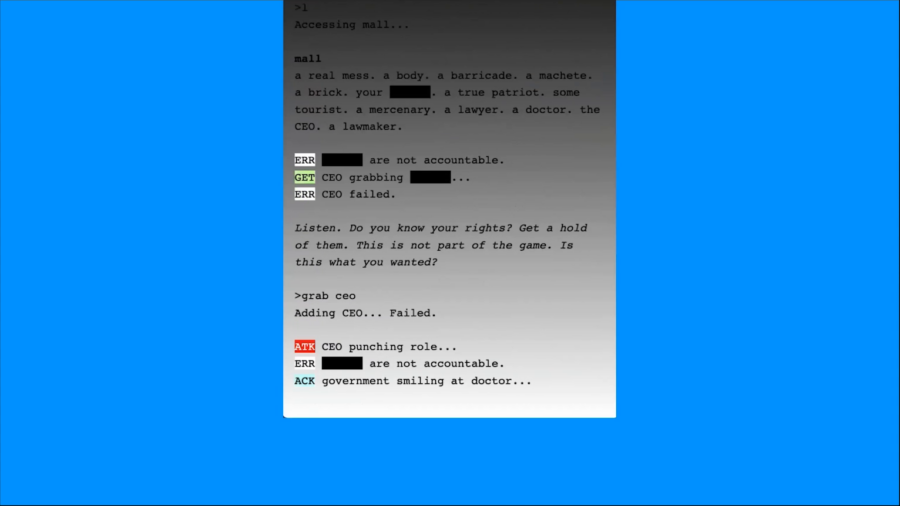

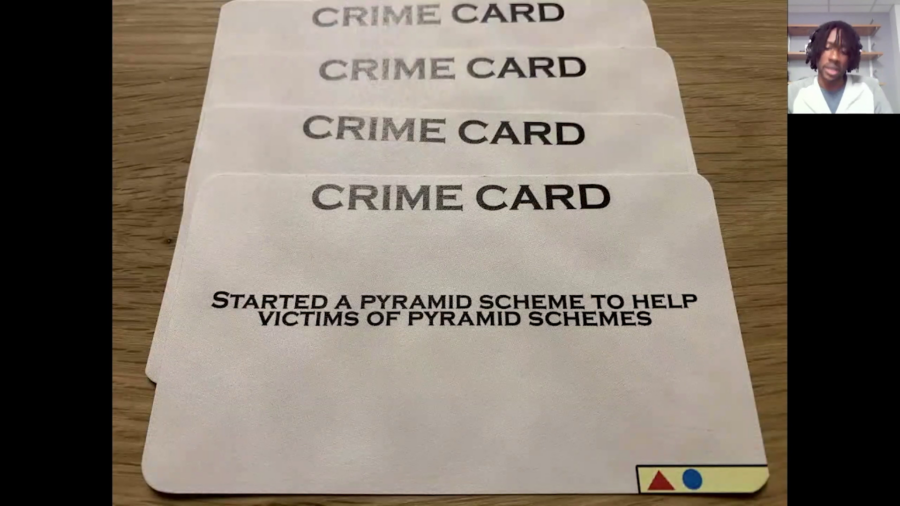

We basically kind of doubled down on this idea that the game had to have the performance of the truth at the core of it. So we eliminated the spoken poetry because in the performance of the truth the words don’t really matter at all.

The conceit is that you’re a ball of ink on the national mall and you’re trying to get to the Supreme Courthouse in order to sort of argue your case.

I’m really really interested in seeing what happens when two people who know each other really well start to play. Because the people you know well, you get to know their tells when they tell a lie, or at least maybe you think you do.

What struck me first about the Third Amendment is that it’s the only part of the Constitution that deals directly with the relationship between the rights of individuals and the military in both peace and war.