Golan Levin: Welcome back to Shall Make, Shall Be. Our next speaker is Andy Malone. Andy Malone holds a Bachelor of Architecture degree from the University of Detroit Mercy, has worked in the exhibit design and custom furniture industry for over twenty-five years. Notable clients of Andy Malone’s include Google, Twitch, Konami, Salesforce, Dolby, LG, Dodge, HP, T‑Mobile, and Bethesda Games. His playable sculptures and games have been shown in over seventy-five exhibitions since 1995 including two recent solo exhibitions, Play Room, and Happy Accidents.

As a curator of the game arts, Andy Malone has co-organized Game Show Detroit in 2006 at the Contemporary Art Institute of Detroit, and Game Show New York City in 2011, at Columbia University. Malone also curated the Bravo! Bravo! Art Exhibition at the Detroit Opera House in 2004 and 2005. Malone currently serves as Vice President of Hatch, an interdisciplinary arts center in Hamtramck, Michigan.

Friends, please welcome Andy Malone.

Andy Malone: Thank you very much. And thank you everyone for tuning in. So today I’m just going to talk very briefly about some of my past projects. And then hopefully that’ll provide some context for my Second Amendment piece for the upcoming Shall Make, Shall Be show.

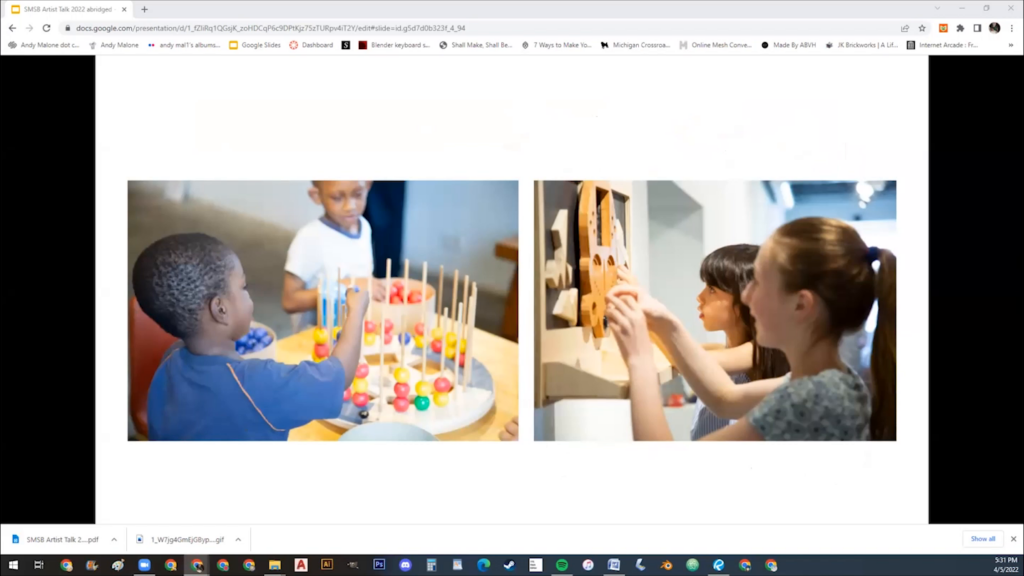

So my name is Andy Malone and I make interactive sculptures and games. For the most part, my work is intended to be physically handled and manipulated. So by pressing a button or turning a crank, drawing a picture or moving a game piece, the viewer engages with the work and they complete its purpose.

So I exhibit in traditional galleries and museum spaces, but the work is intended to be manipulated by the viewer. So to appreciate it, the viewer must break the first rule of most art spaces: do not touch. And it throws people off for a few seconds but soon they figure it all out.

So the toy-like nature of my work can be subversive. It draws the viewer in, and I actually like to call the viewer the player, or the collaborator. But it also serves as an entry point for some more provocative themes. So I strive to create some meaningful experiences through interaction and community-building.

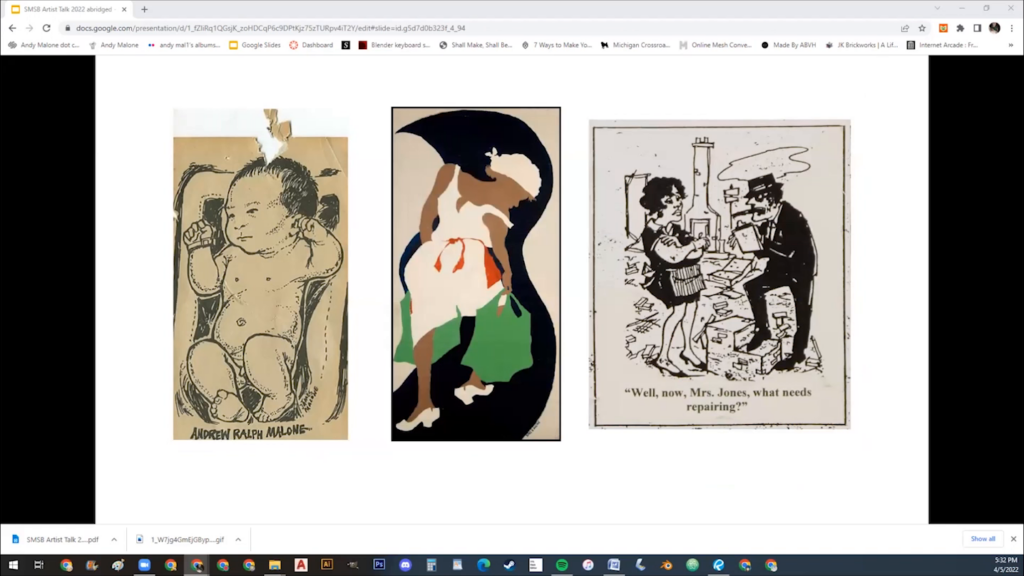

So I was born on the West Side of Detroit in the 1970s. My mom was a teacher, my dad was a painter and illustrator. And in addition to painting and making my birth announcement, my dad drew a semi-regular comic strip that was published in Detroit and Atlanta. And his work was also featured in an international collection of cartoons, which he was often one of the few black cartoonists represented.

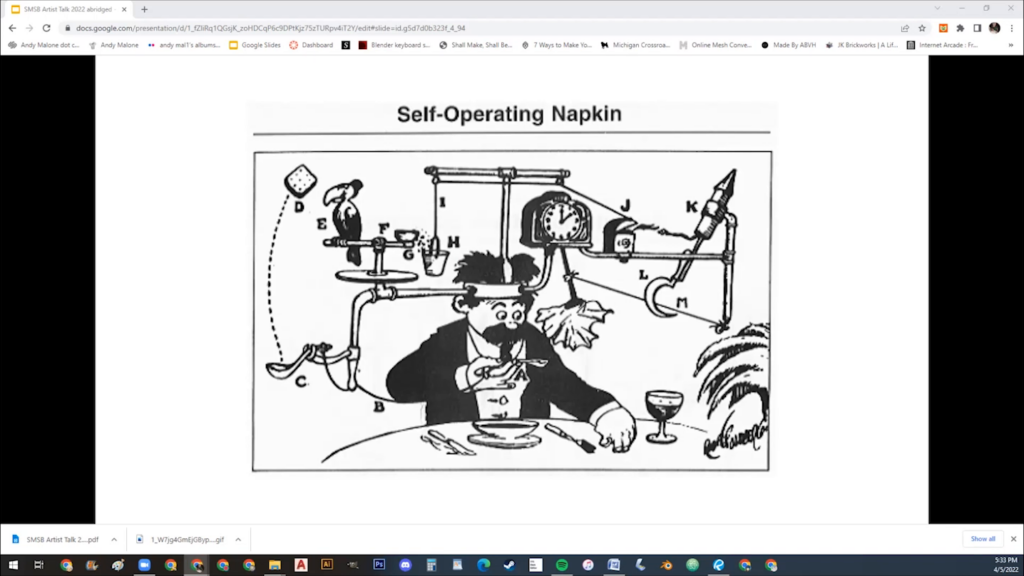

So one of these books, it featured a retrospective of Rube Goldberg. And as a child I was fascinated by his whimsical chain reaction machines. Rube Goldberg made mechanisms humorous and relatable. And so this planted seeds for my interest in technical drawings and artistic machines.

https://vimeo.com/251542251

[These following descriptions narrate the first ~1:42 of the above video.]

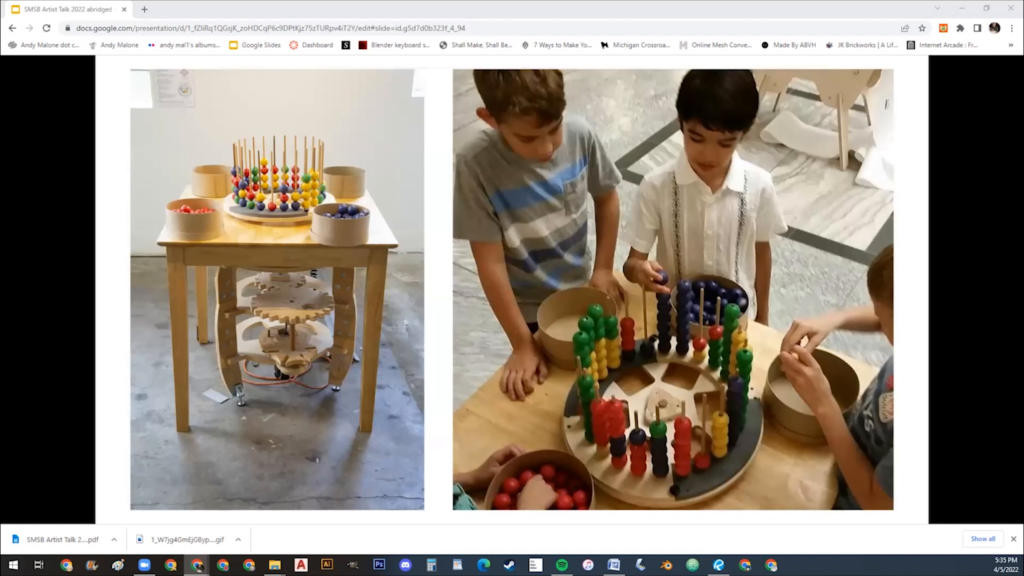

So I went to architecture school, but I did not inherit my dad’s drawing abilities. So I enjoyed making automata and tabletop games out of wood. And I called them playable sculptures. So these prototype abstract strategy games were an attempt to interpret some theoretical concepts in game mechanics and to explore how players interact with the environment and each other.

This video was created for a gallery that was exhibiting my games, and they wanted to have something on a loop next to it so that people could see how the game was played. So this particular one’s called Meander, and the concept behind it is that everyone’s playing simultaneously. And they’re moving their pieces simultaneously, so they all need to be in sync.

This next game is called Ex Cross and it’s another abstract strategy game about shifting ideologies. And players need to modify their systems of movement by whatever symbol is on the top of their piece. So Xes move diagonally, crosses orthogonally. And it’s based on the conflicting philosophies of Martin Luther King and Malcolm X.

And this game is called Nexus and it’s a—these are all working titles, by the way. But it’s another prototype and it features a shifting topography. So it needs to be reconfigured to create paths and ways to victory. And also the pieces can be placed on the sides.

There’s a few more—actually there’s a lot more but I’m not gonna get into it because I want to be conscious of time. All these games have a basic set of rules, but I prefer to have the player develop their own rules by playing with the items and seeing what happens intuitively. So this is my favorite set of rules that someone developed for one of the games. I think if someone can follow those rules I think they’re pretty good.

So, my son Martin is an amazing kid. But he’s averse to most forms of competition. And so Quarturn is a game that I made with the intention of creating something that he would enjoy.

https://vimeo.com/251546797

So this is a simultaneous turn-less game. So, people playing it don’t need to wait for everyone else to play, they’re all playing at the same time. And so everyone needs to be syncopated. And what you’re doing is it’s essentially a game of Connect Four for four players, played on a rotating board. So the goal is the same as Connect Four: try to get four in a row. I believe this game’s very immersive, and I believe that when you have a game that’s immersive it can be called art.

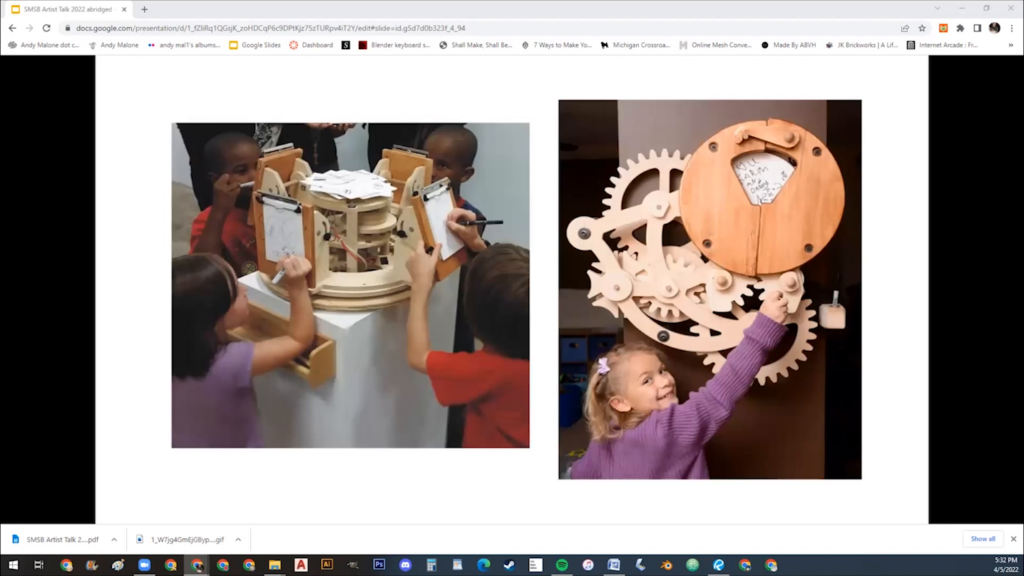

So my artistic philosophy is sort of a work in progress. At this moment I would say I’m creating environments for people to play, and learn, and be transformed. I love moments like this when the traditional boundaries of the gallery are blurred and the viewers become collaborators. So I feel like these pieces sort of informed my work for the Shall Make, Shall Be exhibition.

So with that introduction, I’m sure you’re probably wondering how this sorta mild-mannered game designer/kinetic sculpture artist became inspired by the Second Amendment, commonly known as the right to bear arms.

Well, here’s a quick story. Until recently I had a pretty negative impression of guns. I never felt the need to carry one, and I didn’t like the way it made people act. I didn’t like the sound it made. And I didn’t like the damage that guns cause.

So one of my friends who’s a self-defense advocate, he thought it was absurd that I had such strong opinions about guns but never fired one in my life. So he asserted that— Actually, I wrote it down because I didn’t want to get the quote wrong. “An armed populace is able to control their own destiny and not be a victim of fate.” And he reminded me that the Civil Rights Movement relied on armed volunteers.

So he challenged me, or guilted me, depending on how you look at it, to not be afraid of the tool. So I went to visit a gun range a few times. And I’m glad I did, because it eliminated the mystery of firearms and allowed me to look at the Second Amendment more objectively.

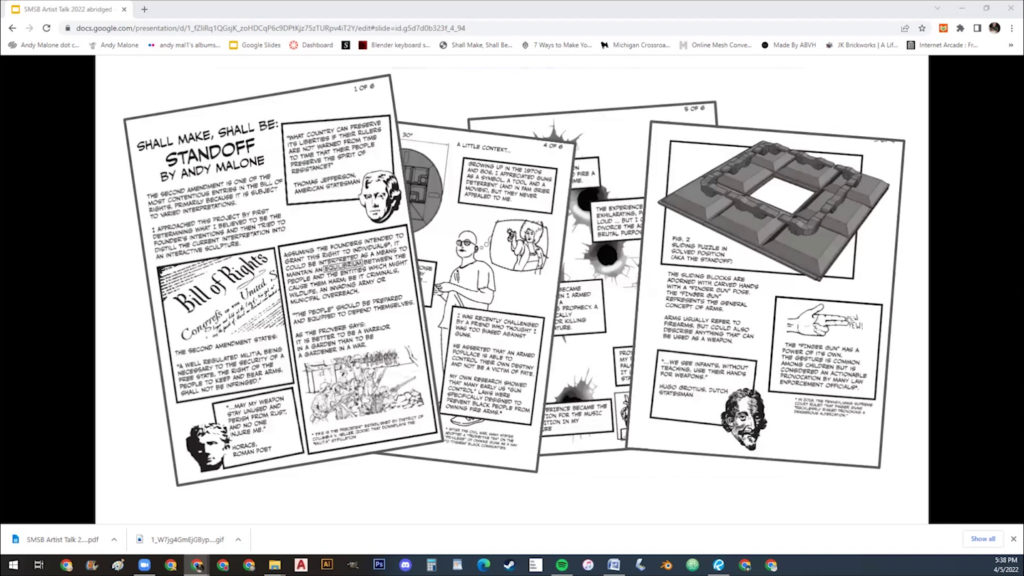

So the goal of this project was to think critically about both sides of the debate and to challenge my own point of view. So to organize my thoughts I sort of went to the familiar comic format. I wanted to create sort of a cohesive narrative.

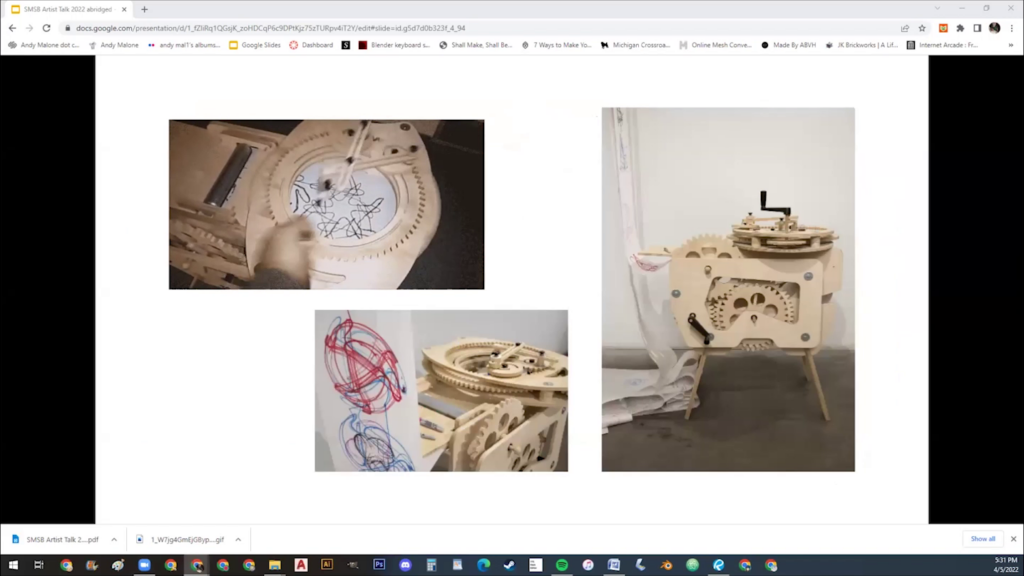

So the Second Amendment’s a contentious subject. I don’t need to remind you of that. And it was a tough thing to for me to get my brain around. The first thing I had to do is realize I didn’t need to be an expert on it. And I wish I would have gotten that through my head before, because I was doing a lot of research and felt…unqualified. But then I realized we’re all commenting as artists on these amendments. So I challenged myself to think about it objectively and not politically. And after a lot of sketches I determined what I wanted to do is create a penny arcade-style game.

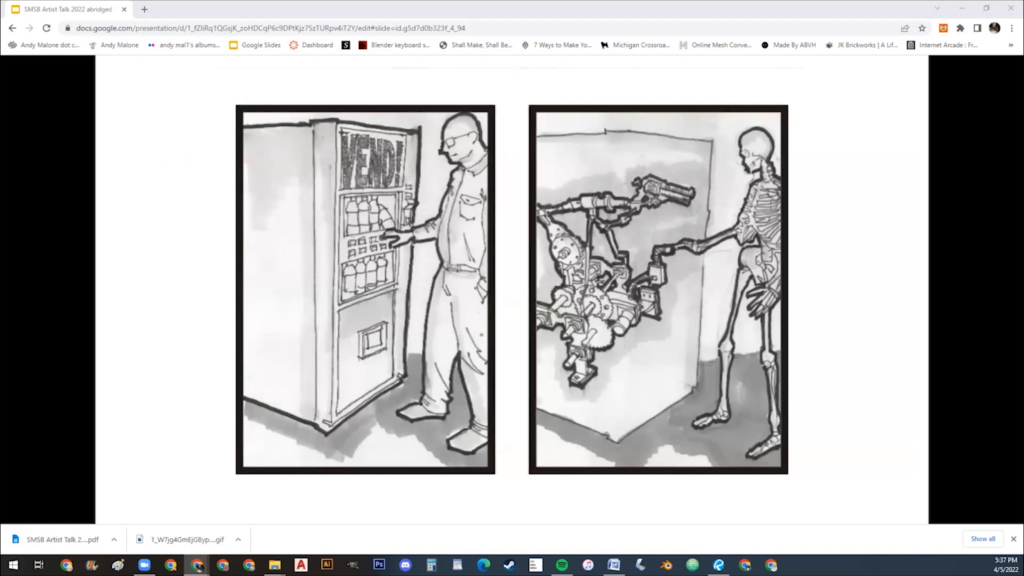

So the player would approach this table, which had a puzzle. And they would complete the puzzle and the puzzle would represent the utopian version of the Amendment. And then that would trigger some animations and a music composition on the wall that’s more of a comment on gun culture today. So I wanted to create sort of a cause-and-effect relationship between the puzzle and the sort of messy reality.

So here’s the idealistic interpretation. The Second Amendment renders any prohibitive regulations on arms unconstitutional, because the founders correlated arms with perseverance and independence. So for many Americans being armed was a way to maintain an equilibrium—and “equilibrium” is the operative word here—between people and the things that might do them harm. So in this utopian vision, the right to bear arms maintains a level playing field and it also is afforded to all able-bodied citizens, no exceptions. Notice I said “utopian.” That’s not how it is in real life. But the people should be prepared and equipped to defend themselves, to maintain an equilibrium in the pursuit of life, liberty, and happiness. So as the proverb says, it’s better to be a warrior in the garden than a gardener at war. In other words, it’s better to have a gun and not use it than to need one and it’s not there.

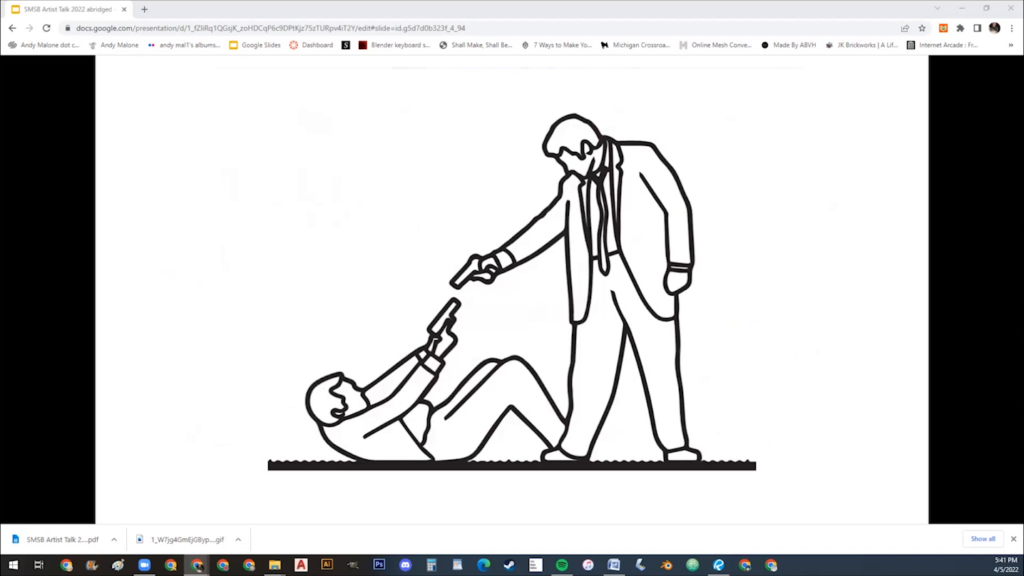

So for my project, like I said equilibrium was the operative word and a balance of powers is also known as a standoff, which is the title of my project. And a standoff was a stalemate or deadlock between two people in conflict. An armed standoff occurs when everybody points their weapons at each other and they all become paralyzed by the fear of mutual destruction. An armed standoff can take many forms and is common in pop culture. Games and puzzles often distill concepts and ideas into simple simulations, so I wanted to make an abstract puzzle that when completed sorta conveyed a sense of equilibrium or an uneasy peace.

So I was drawn to the concept of finger guns as a metaphor. I also didn’t want to use actual guns in this project. That was sort of a challenge for myself, to not make this about shooting things or make this about overt violence.

So the gesture of using your hand to mimic a gun is often used in harmless or humorous contexts, but it has a certain power. Like for example in your state of Pennsylvania, finger guns were ruled that they provide a reckless provocation, which means you can actually be arrested for using a finger gun on a policemen in Pennsylvania.

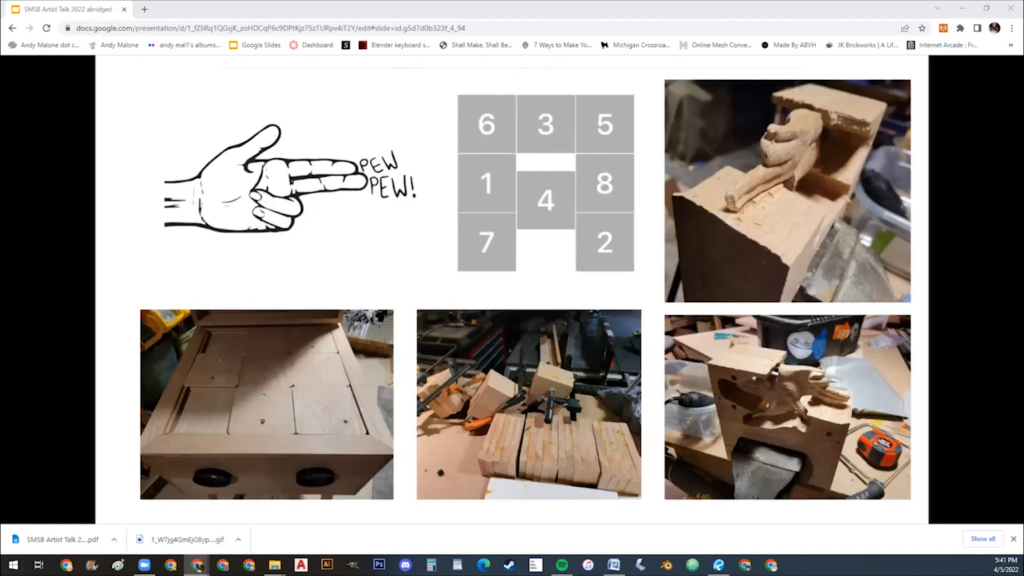

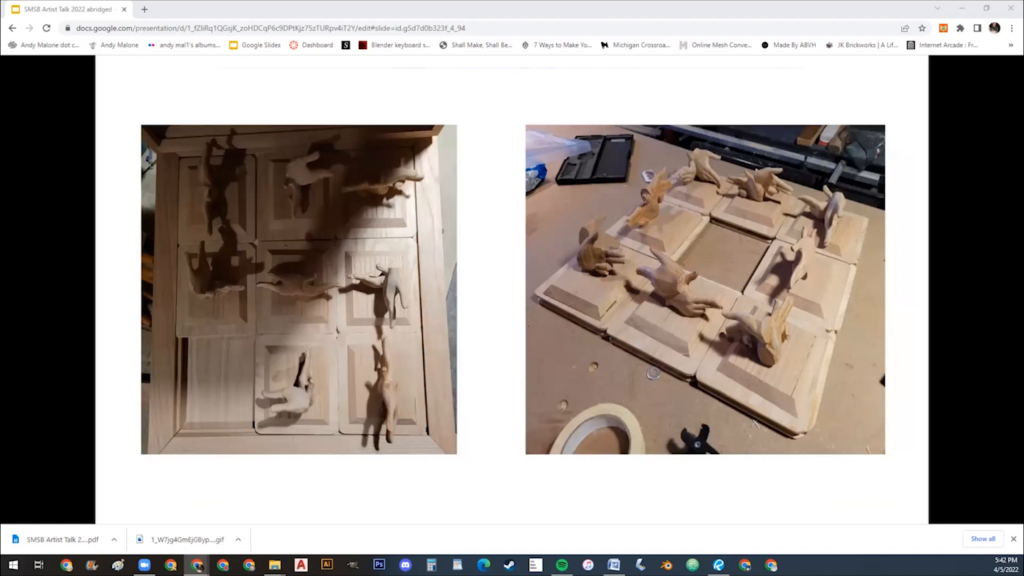

So I started carving the hands out of blocks of solid oak. And then I started creating the puzzle. Each block is adorned with a pair of carved wooden hands. There’s ones that are 90 degrees each from each other in the corners. And they’re in line on the sides. So the object of the puzzle is to neutralize all of the fingers so they’re all pointing at each other and the fingers are basically canceling each other out. So at that point you’ve achieved the classic standoff.

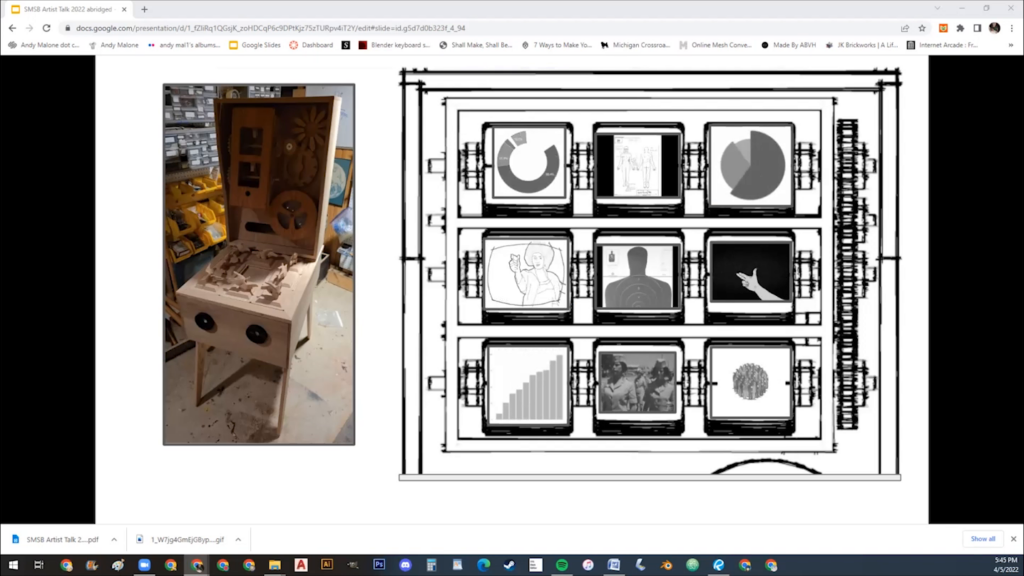

So once the puzzle’s solved, there’s some buttons on the front and they’re powered up and they activate some mechanisms on the back wall. These drawings are an older prototype but the concept is still the same. The back wall is a commentary on gun culture in America. The abstracted simplicity of the puzzle gives away to more of a complicated legacy of racism and classism and cruelty.

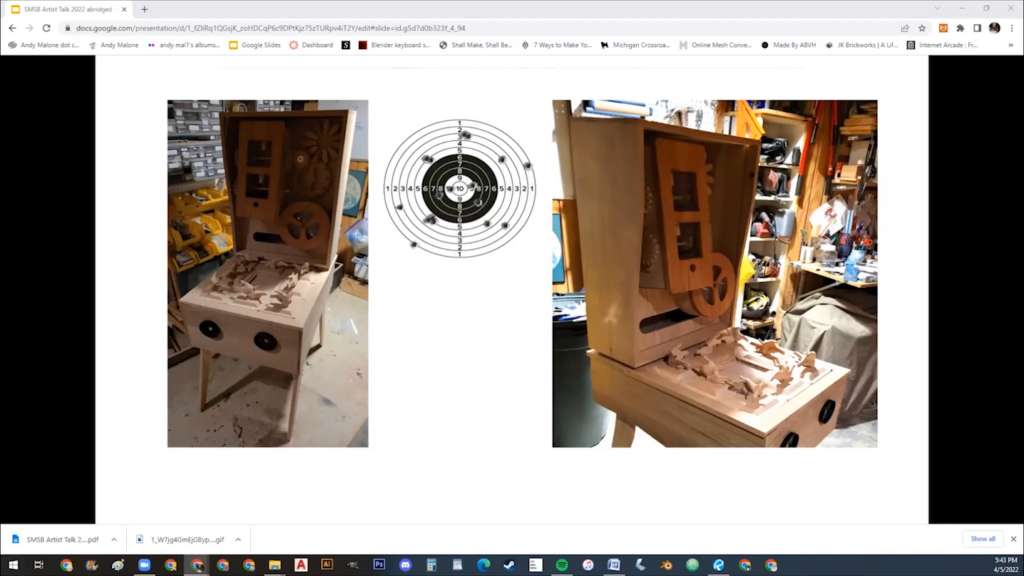

So when the left button is pressed, a music composition will play. And this is a music box mechanism that’s triggered by the locations of bullet holes from my paper target. And this compositions’s called “Aversion Therapy,” to sort of represent my initial ambiguity toward firearms. And this is a good example of an accidental composition, sort of in the spirit of John Cage. It’s a composition that’s free of the composer’s will. In other words it’s interesting but it might not be uh…melodic.

Additionally there will be two drums, one at three beats per minute and one at forty-five beats per minute. And this will represent the rate of fire between a Revolutionary-era musket and an AR-15 respectively.

So when the right button’s pressed, a flipbook mechanism’s activated and multiple animations will play simultaneously, creating sort of a looping collage. The animations represent data about guns in the US and images associated with guns. And it’s my thought that we primarily don’t talk much about the root causes of gun violence because we haven’t allowed ourselves to collect the data. And so the graphs are heavily influenced by WEB DuBois’ data portraits that he exhibited in Paris in 1900.

And I believe the Second Amendment is not necessarily the only cause of this conflict, but I think it’s created this polarizing effect on the debate. And I wanted this to be a little overwhelming. So the player can choose to either focus on details or the larger picture.

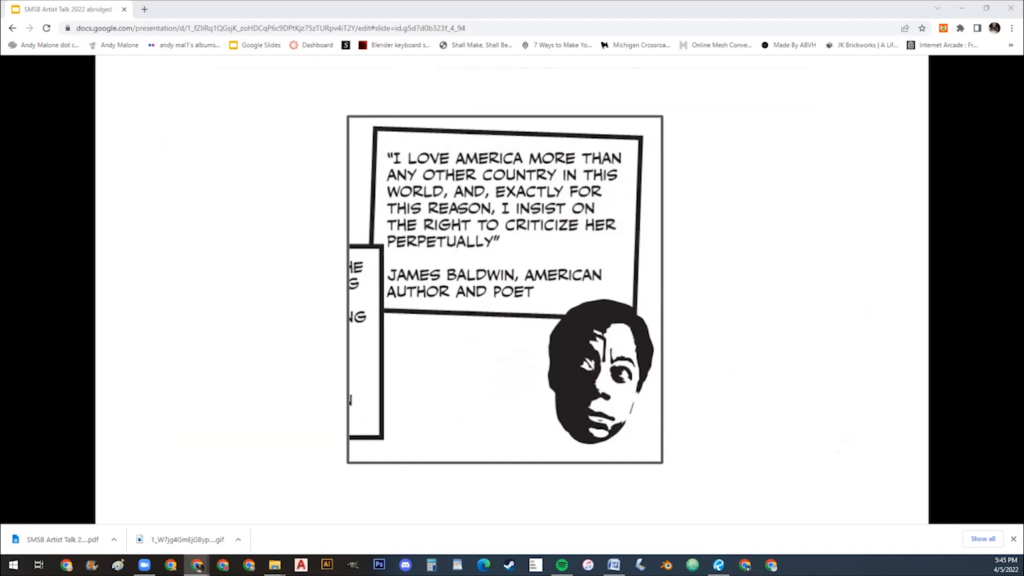

So I’d like to conclude this presentation with a quote from James Baldwin. He said, I love America more than any other country in the world and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.

So Standoff is about appreciating the spirit of the Second Amendment while still despising gun violence. And it’s also about reconciling American mythology with American brutality. And like America itself, I think the Second Amendment can be many things at the same time. Thank you.