Golan Levin: Welcome back everyone to Shall Make, Shall Be. Next up we are joined by Ian McNeely and Arnab Chakravarty, both from the Broken Ghost Immersives collective, and their collaborator MeeNa Ko, also known as Moaw!.

Ian McNeely holds an MFA in Theater Arts from Brown University, where he wrote and produced a series of original rock operas. McNeely was awarded the Oregon Shakespeare Festival’s 2009 Rex Rabold Fellowship and delivered the keynote speech at their annual HIV/AIDS fundraiser The Daedalus Project. He is the founder and artistic director of Broken Ghost Immersives, which produces theatrical events inspired by games.

Arnab Chakravarty, also from Broken Ghost Immersives, is a designer, technologist and educator with a background in building interfaces for communities overlooked by dominant technology platforms. Previously, he worked as an ethnographer and designer in several multinational organizations. At NYU ITP, his interests have focused on living with the things that he makes, creating immersive experiences for co-liberation, and discovering what makes people touch things.

MeeNa Ko, known professionally as Moaw! is a video game developer specializing in pixel art. They work to build creative communities through game development, bridging dialogues between STEM and art, and have worked professionally with many companies to make games and pixel art advertisements. Outside of commercial work, they design open source game development assets and participate in accessible education initiatives

Folks, I’m pleased to welcome Broken Ghost Immersives and Moaw!. Take it away folks.

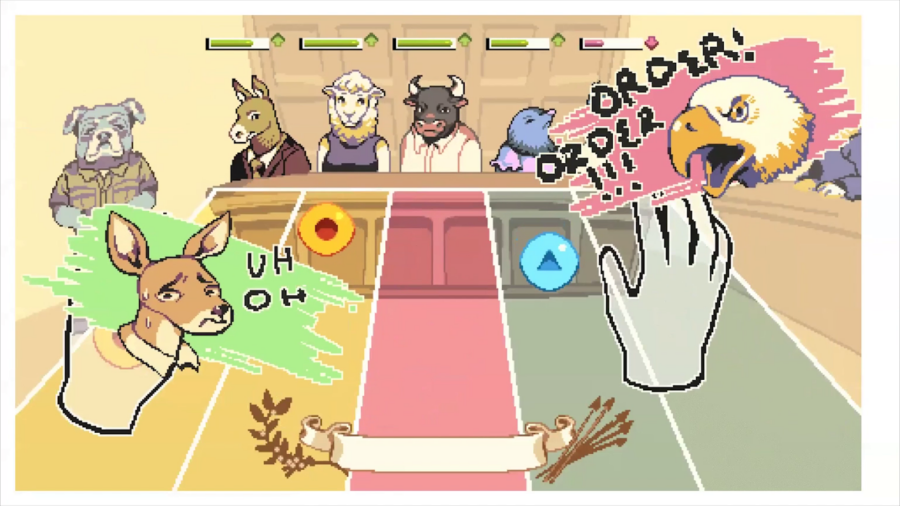

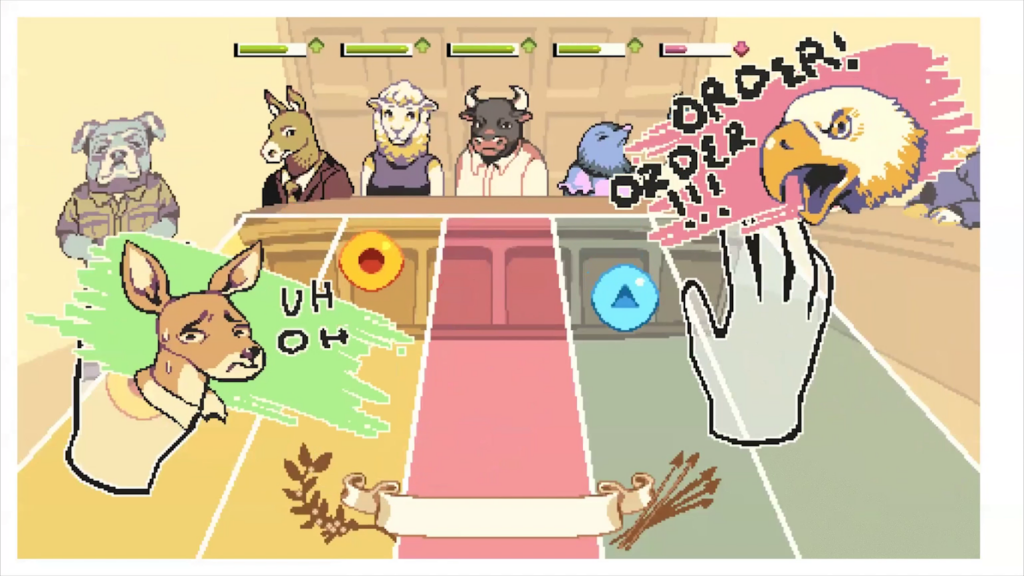

Ian McNeely: Thank you so much for having us. We’re excited to talk about our bespoke arcade game Verbal Gymnastics, all about the US Constitution’s Seventh Amendment. You can see a little bit of our graphic assets there of what the courtroom looks like in our game. And it is a playable work exploring the Seventh Amendment.

A little bit about us. Arnab and I work with an interactive theater company in New York called Broken Ghost Immersives. And we produce wildly interactive stories that have user agency; where audience members get to influence the direction of the plot; they could participate. It’s meant to be very inclusive and very hands-off. We’ve got some pictures there of what these events look like. They’re raucous, and have a lot of creative energy.

So our background that we’re coming to this with is the point of view that people should be involved, they should have control over the steering wheel of what happens, and what better way to explore that than an arcade game?

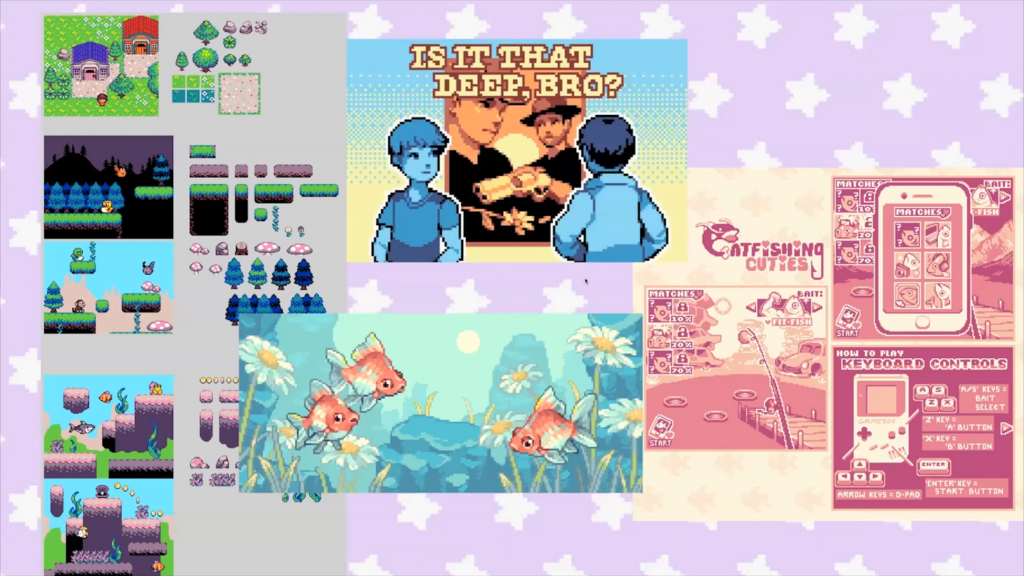

We see here some work, the style of what we’re working with. This is from Moaw!‘s portfolio, this awesome pixel art style that we’ll talk more about later on in the presentation.

Arnab Chakravarty: I think Moaw!, can you talk about yourself?

MeeNa Ko: Yeah. Yeah, hi. Thank you. I’m MeeNa Ko. I use they/them pronouns. Also go by Moaw! online. So, pixel art is a specialty of mine. Working within limitations I think is a great way to teach other artists and technologists about the limitations of the medium and more about the technology that determines those limitations. And I think there are a lot of things for the project that we’re working on that definitely references that era of technology.

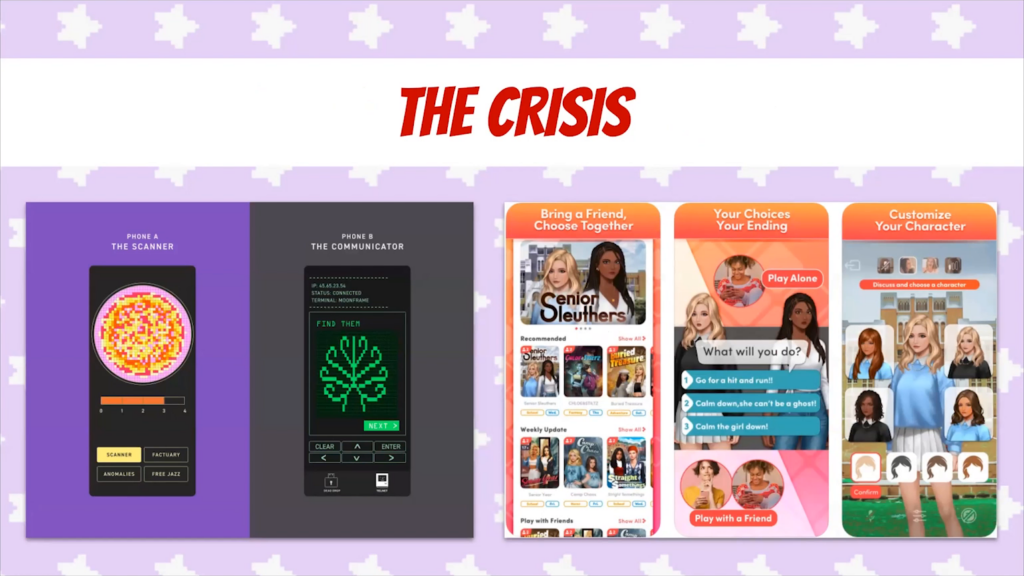

McNeely: So these are some of the samples of the works we produced in New York. The Bunker was a sci-fi immersive. It was in a basement in the Lower East Side and groups of people got to work together. It was kinda like a choose-your-own-adventure where they navigated this plot.

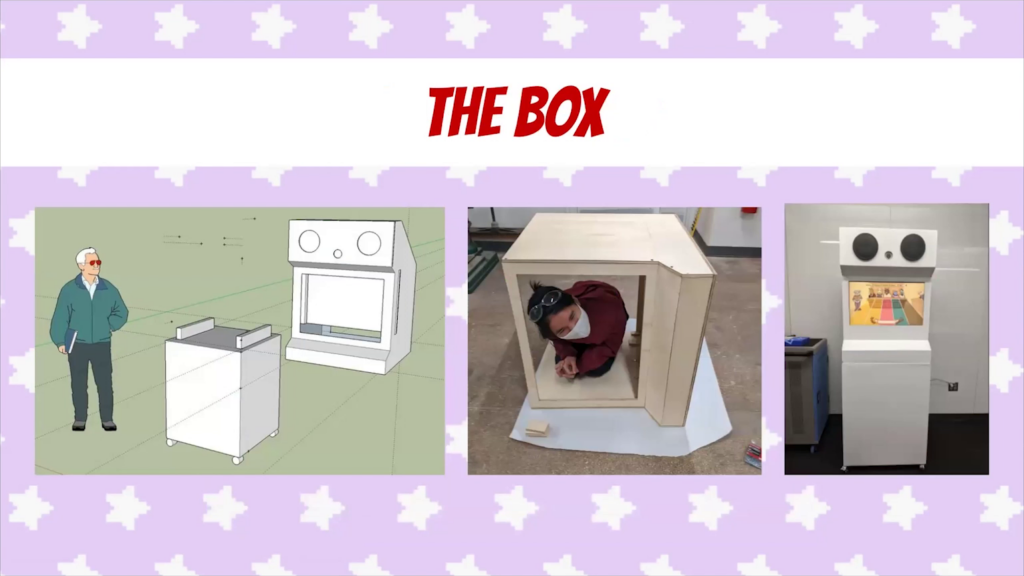

We also produced a supervillain version of the same idea called The Rogues Gallery. And you can see this awesome prop in the middle. It is maybe a prototype of our first arcade game. Arnab made this. Arnab, tell us a little bit about what we’re looking at.

Chakravarty: Yeah. Well this was basically an escape room in a box. The funniest thing was I met Ian on probably my first day in New York. Like I flew in for grad school and [bumped?] into Ian and somehow I just ended up making this escape room in a box for a final in my first semester. And we basically started working every since.

McNeely: So the Seventh Amendment, right. This is where we’re going. It’s the right to a jury trial, in federal civil cases. So, it’s not one that people are super familiar with. It’s one that when we first put our heads together to look for which of the amendments we might want to explore, it sort of called to us, for all the same reasons we wanted to make these interactive theater pieces. I think it called to us because it had a performative element: that lawyers argue in front of a jury. It’s dynamic, like a game, where there’s a winner and a loser, with some kind of a competitive element. And it just felt fun. Court proceedings conjured up images of the entertainment industry.

But, we also couldn’t talk about this without the context of when this call went out. The last two years, COVID has been the biggest changer of how we do things. And obviously if you had to pick the worst industry to try to produce, it was live in-person entertainment in close quarters, interacting and touching stuff together. COVID just crushed it.

So Arnab and I, when the call went out for creators, were in a moment of inflection. And we were pivoting away from live theater, which we just couldn’t do, to digital offerings. And Arnab, you’ve got some pictures on the left from your experiment with Pig Iron Theatre in Philly, right?

Chakravarty: Yeah. It was a sound AI game for two players to play at the same time. So if people were in a bubble they could basically play this game together.

McNeely: Awesome. On the right hand side I’ve got some pictures from what I pivoted to, which was creating this app with a Japanese company called Mixi. It’s a choose-your-own-adventure app for young adults.

But what we were both exploring were how we could take the lessons we’d learned producing interactive theater and apply them to a purely digital context, without any in-person interactivity.

And, lo and behold, this call came out and we decided the Seventh Amendment was the way to go. And we’d like to talk a lot about the inspiration that drew us there. Arnab, you were telling me you have a really unique perspective on our jury system. Tell me about that.

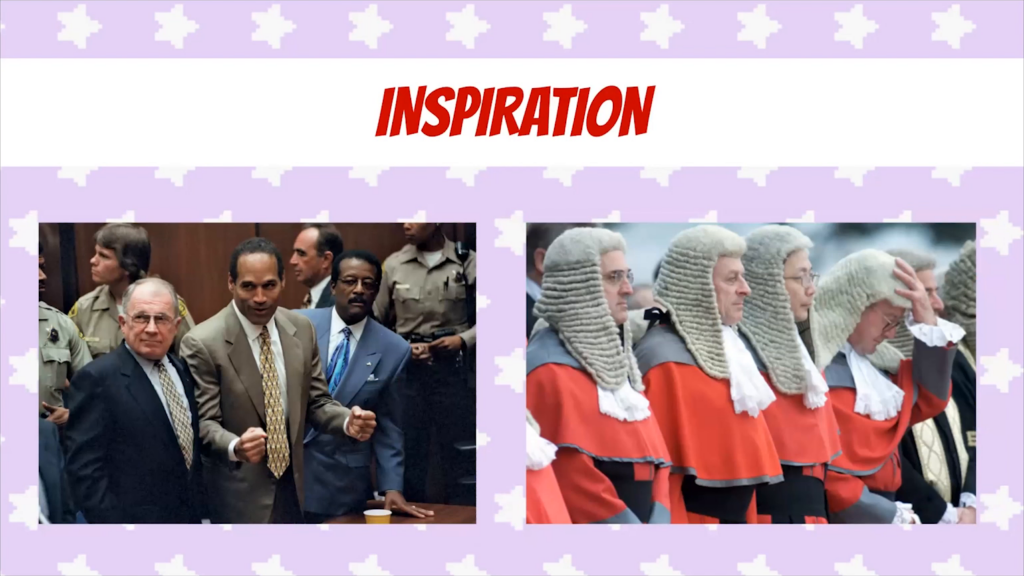

Chakravarty: Well yeah. Because I grew up in India, which is ironic that I am making a game about the Bill of Rights of America without being American? One of the most interesting stories of my life. But I come from a system where it follows the British judge-based system. And my first recollection of anything jury-based was the OJ Simpson trial, which was broadcast into Indian homes because of CNN and cable TV in the early 90s.

McNeely: Isn’t it funny? I feel the same thing, that the impression I got of juries was shaped entirely from what I saw on TV. Better Call Saul is a classic show, but as a kid I remember staying home sick and watching Perry Mason, which is from like the 60s, black and white. And the whole thing just always turns on how they talk to the jury.

And so the Seventh Amendment, the right to a jury trial, is an exciting premise because we have this jury of your peers who are wildly variable in what they can find. One of the reasons—we learned this from the lawyer that we consulted with—is that one of the reasons people don’t often choose to go to jury trials in civil cases is because they have no idea what people will do. It’s hard to predict how human beings will interact with this system. So this was the element we wanted to build the whole game around, these unreliable actors. How do you hack this element and make a whole game around convincing these humans to your point of view.

Chakravarty: So yeah, I think when we started we basically wanted to make a game in which players go head to head against each other, and their bodies are being tracked. And they have to squeeze through these insanely-difficult holes as their argument kind of progresses during the gameplay. We imagined that people would kind of match the beat to a spoken recorded rhyme that was playing in the background. And if they basically missed any of these holes that they were kind of putting themselves in, their scores would reduce and basically at the end of the game whoever kind of performed, won.

This had kind of majorly two issues. When we first tried it out to play this game, body tracking in Unity was extremely slow based on the algorithms that we had access to say a year ago. And as an arcade expedience, one player waiting for the other player to finish was extremely boring. And the way that we had imagined it, it would kind of go on for fifteen, twenty minutes, which was a complete no-no in a gallery setting.

So it’s also then when we kind of started talking to a lot of legal experts. And what we realized was that underneath the jury system, which kind of was established as a hedge by Americans to protect themselves against the British when America was still being controlled by the British, it became a way for the majority in America to kind of inflict their prejudices, their biases onto the minorities, which has ebbed and flowed based on the decade that you select.

So we basically kind of doubled down on this idea that the game had to have the performance of the truth at the core of it. So we eliminated the spoken poetry because in the performance of the truth the words don’t really matter at all. And the idea of catching the vibes of the jury to make sure that basically they win.

So in its current iteration how the game functions is basically at the start you’re given a choice of seven members. It’s a single-player game. And you have to select five. Each of them would respond to a certain kind of color, which we are calling the vibes, which is based on this idea of logos/pathos/ethos, the three predominant ways of discourse as defined by the Greeks.

But the idea is playing using their hands have to cast these vibes, and if they cast the wrong vibes for each of these jury members, they lose points and at the end they are awarded a very unfair result.

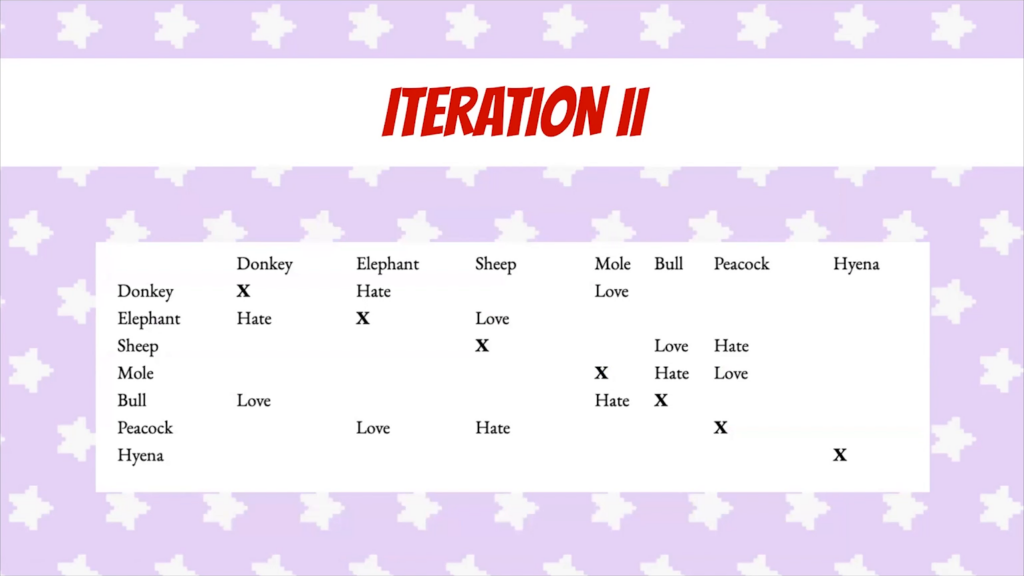

And this is what’s going on on the surface. But we also built in a mechanism at the bottom of it, this idea that unknown to the players certain animals hated certain other animals. So if you ended up in a scenario where your defendant was a peacock, or it was a donkey, and most of the jury members were elephants, there was no way you were going to win no matter how much you performed. So the idea was that in this arcade game players might end up in a situation where they performed great but the final award that they get is extremely low. Which kind of makes people question the inherent unfairness of the system and is something that we want to elicit.

There are hints to it that the players will kind of get while selecting the jury members. But again, it won’t be exposed to them initially. And what we imagine is that once they finish they’ll have a chance to read through the game design document so that they understand why they failed even when they kind of won. So the larger-level idea we want to leave players with, and the question is, even if you performed well and you won, was justice actually served?

And I’ll skip over the technology slide, but we also kind of got a chance to build a great arcade machine which we’ve already finished, and are currently in progress of wrapping everything up, which I’ll hand over to MeeNa to talk about.

Ko: Hi, thank you so so much. So as Arnab covered before, communicating the significance of performance and gaze is critical to this game. There’s a really interesting tension between what each character is experiencing internally and what they are externally expressing.

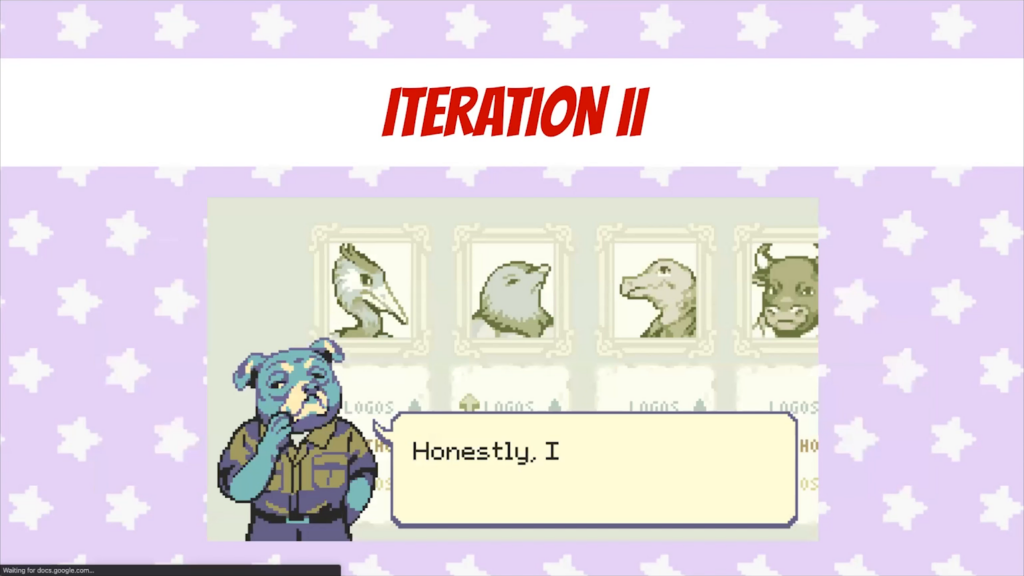

So while much of the jury’s biases are hidden through the code, the player has to assume these biases through gameplay and the reaction of the members of the court. So portraiture is a huge priority in terms of assets, as the expressions of court members carry significant thematic and mechanical weight. So for example characters like the bailiff, who’s that little dog character you’ve seen throughout our presentation, and the defendant have a heightened awareness of the jury’s gaze.

The bailiff plays the role of the insider. Having had years of experience in the court, he’s able to read a jury. When you’re on the jury selection screen, he’s a bit of a gossip. He’s not afraid to throw asides to the player and let them know how their odds are looking. The defendant, in turn being very aware of how they’re perceived and their own species bias, will communicate throughout the case how anxious they’re feeling, also giving more context into what the species biases may be within the jury.

Other fun visual challenges to consider were making text and performance dynamic. This is a challenge long remedied by fighting games, which express immense dynamicism through text and games effects which pop out throughout play. These effects communicate physical impact, character impact. Capcom, which is a game studio long famous for its fighting games, takes a really unique approach with these effects through their game Phoenix Wright, which is a legal drama with part visual novel mystery and has a lot of fighting game flair. Phoenix Wright uses the impact of exclamations, which you can see to the left of the slide, to provide weight to moments in its narrative.

So taking notes from Phoenix Wright and other fighting games, our goal with visual effects was to provide an equally informative but also visually stressful experience for the player. Just constant stimulus everywhere while you’re playing. This also goes back to the nature of 8‑bit and the visual language of the arcade era, right, where arcade era games just visually demanded and screamed attention from its players and also bystanders walking around the arcade. Our cabinet is proud to boast the same visual obnoxiousness throughout its play.

So you can see in the next slide some of the gameplay here. The hands are popping the vibes along the tracks as some of the vibes are collected. You can see both the judge and your defendant kind of popping in expressing and reacting to what is happening throughout play.

Chakravarty: Cool. So yeah, I think that wraps up our presentation. We hope you’ll all come on July 4th and play this game with us. This has been a long road of really amazing twists and turns. But we are so glad to be here finally doing this in a way which was definitely not how we started to imagine it, but we are very proud to kind of have it in the position that we have.

Yeah, that’s it. Thank you.

Levin: And thank you Arnab, Ian, and MeeNa. Thank you so much. This was lovely. And that was really popping at the end there. Thank you. That was fantastic to to see.