Wanuri Kahiu: Hi. My name is Wanuri Kahiu. I’m just gonna start with the trailer of my film Rafiki and then we’ll get started after.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7M_-ucSaFpU

In 2018, Rafiki was banned. It was banned because it was a same-sex film based on a story called Jambula Tree.

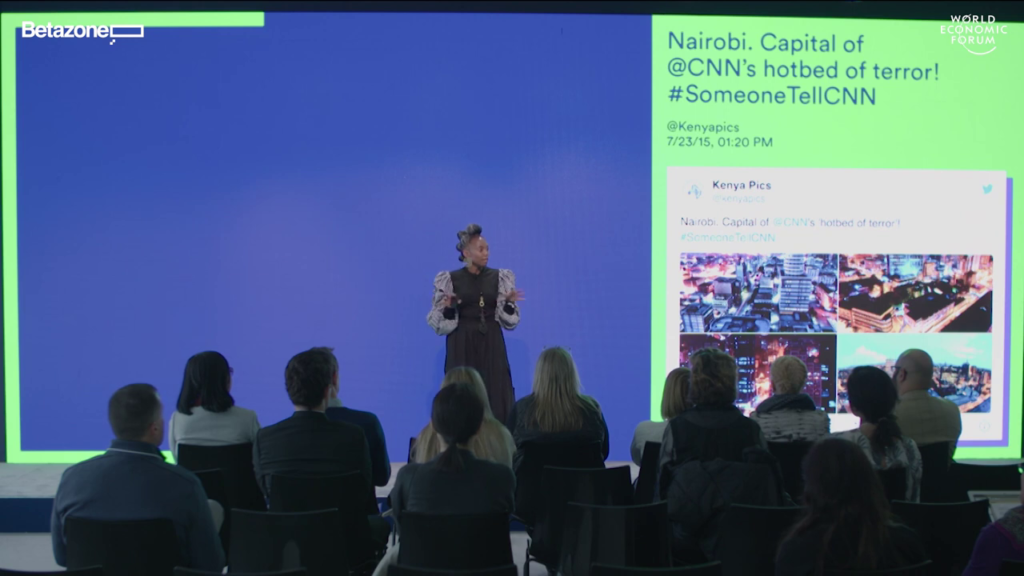

And though it wasn’t a shock to many others it was quite a surprise to me, because the Kenya that I know, the Kenya that I love, is always full of music, concerts, the beautiful sounds of Muthoni Drummmer Queen, the absolute wonderful voice of artists like Blinky Bill. I mean, we have extraordinary artists and a very, very, very active social media who call themselves KOT—Kenyans on Twitter—who do not stand for anything.

So when anybody says anything untoward about Kenya, or the country, or anybody, they really attack them and even come up with a “SomeoneTell” hashtag. So it was #SomeoneTellCNN, it was #SomeoneTellNewYorkTimes. I mean, we really go hard when we do not like the way people speak about us. So we’re very vocal. We practice our freedoms. And freedom of expression and freedom speech is one of the things that we really really practice.

So when the film was banned, I was really, really, really surprised. And what surprised me the most about the ban was the reason the Kenya Film Classification Board gave. They gave the reason that the film was not remorseful enough. They said that if I change the ending of the film and make it more remorseful, then they would give me a rating. Because they didn’t like the idea of legitimizing, or normalizing, the LGBT community in Kenya. Which was ridiculous.

But what it did, what the ban did, meant my parents couldn’t see the work. They only heard an officer of the government say that my work was so absurd, was so vile, that no voting adult in Kenya could see it. That’s all they heard. And then the film was banned. So even though they wanted to be able to advocate and support the work, they couldn’t, because they had no concept of the work that I had done.

But it also meant that it pits you against your government. It makes you feel like your work is somehow unpatriotic. Because they’re saying that the work that you’ve done cannot be seen in your own home country, and the work that you’ve done goes against the national norms and values of the country. Which I don’t believe to be so.

But when they said it was remorseful, that really hurt. Because one of the things I pride myself at being is an Afrobubblegumist. Now, Afrobubblegum is fun, fierce, and frivolous African art. It is art that is full of joy. It is art that is full of imagination. It is art that is just—it just sings with hope and joy at every point. And that is what is so fabulous about this idea of Afrobubblegum.

But not all art from Africa is Afrobubblegum work. In fact we created an Afrobubblegum test, kind of like the Bechdel test, to figure out what art could be considered Afrobubblegum. And the questions that we asked are: Are two or more Africans in this piece sick or dying? Are two or more Africans in need of saving? Are two or more Africans desperate, hopeless, or lost? And we found that any work that says no to any of these questions would qualify as Afrobubblegum work.

But the thing about Afrobubblegum work is that it’s not only modern art. When you stretch back into the history of African art, African tradition, African’s fantasies, creation myths, they’re all full of joy. They’re all full of laughter. And they’re not remorseful.

And when I started to dig and investigate the kinds of different work that was being banned across Africa, we found that the work that was being banned was the work that was considered not remorseful. It was the work that was full of joy and hope that was being banned.

In 2014, a wonderful collective called The Nest Collective, who make brilliant work, made a film called Stories Of Our Lives that was based on real-life stories of the LGBT community in Kenya. They then fictionalized the piece and they made it into these beautiful vignettes that were released in Toronto at the Toronto Film Festival. Stories Of Our Lives was banned. The producer was jailed for a hard stint. And now, George Gachara, the producer of the film, says that his film now lives in exile.

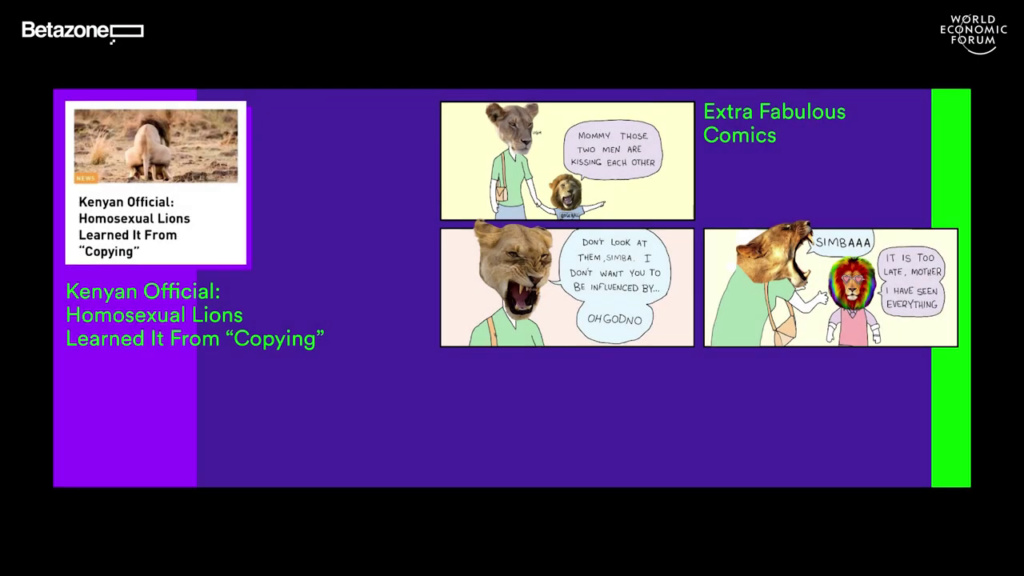

But. The Kenya Film Classification Board does not only ban films. They’ve extended their parameters to banning music, musicians, statues, and even lions. There was a picture of two male lions mounting that circulated at one point. And what happened is, the Kenya Film Classification Board said that these two mounting lions should be separated, should be counseled, and even suggested that they “learnt that behavior” from tourists in the national park that they had seen, and were replicating that kind of behavior.

But the laws that were used to ban the films, that are used to ban art, and that’re used to ban lions, are old colonial laws or remnants of colonial laws. They were laws that were created before our constitution in 2010. They’re laws that are based on the sedition laws that banned Pan-Africanists like CLR James, George Padmore, Kwame Nkrumah, and Jomo Kenyatta in the late 30s in London, where they would come and disrupt the work that the Pan-Africans were doing. They would dismantle the printing presses that created their journals that were circulated across the UK and also in Africa. But they used these laws, these sedition laws, and they continue to use these sedition laws to ban work.

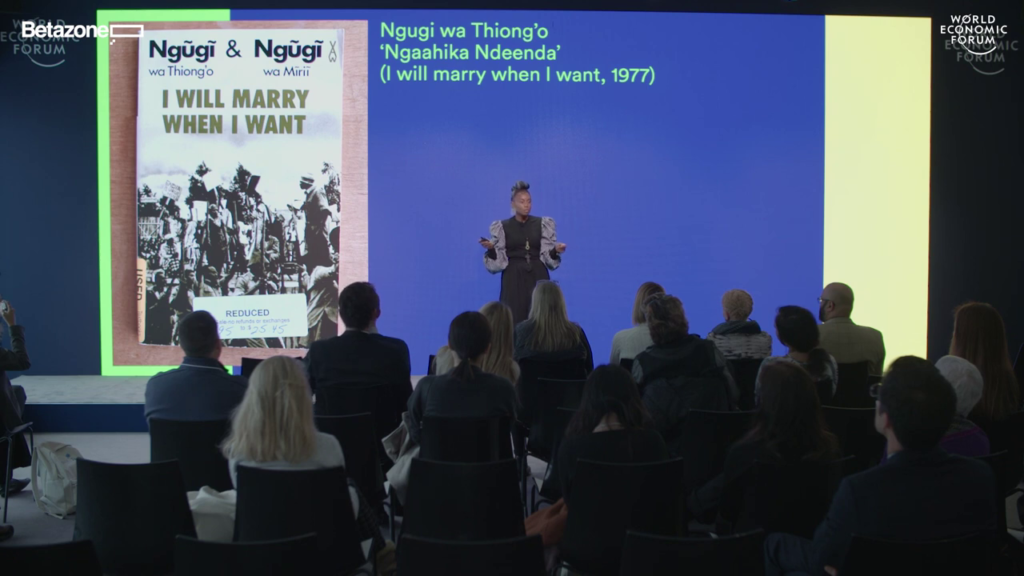

So, in the early 1980s one of our great literary giants, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s work was banned, because of a comedy he created Ngaahika Ndeenda, which is “I Will Marry When I Want.” And it was a story about class politics. It was a story about marriage. It was a story about power dynamics. And when this play was banned after a six-week run to a full audience, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o was jailed for one year without a trial and without a charge. After that, he was fired from his job at the University of Nairobi, and then went into exile. So we lost one of our greats for a comedy he created, his non-remorseful work.

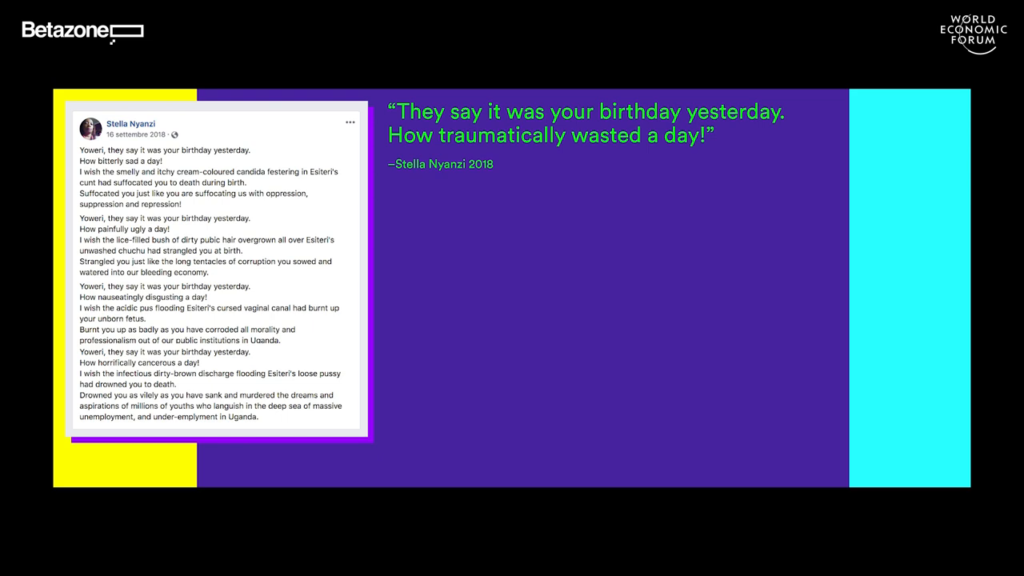

In 2018 Dr. Stella Nyanzi was banned for a poem that she wrote against the president. And in the poem she was protesting the death of women, and the disappearance of women, and the murder of women. She was also protesting the corruption that was happening.

Now, the poem…was a little bit…risqué. But she used what she called “radical rudeness” to arouse the work, to arouse the thoughts, of leaders. But. Because of this poem that she wrote, Stella Nyanzi is still in jail until today.

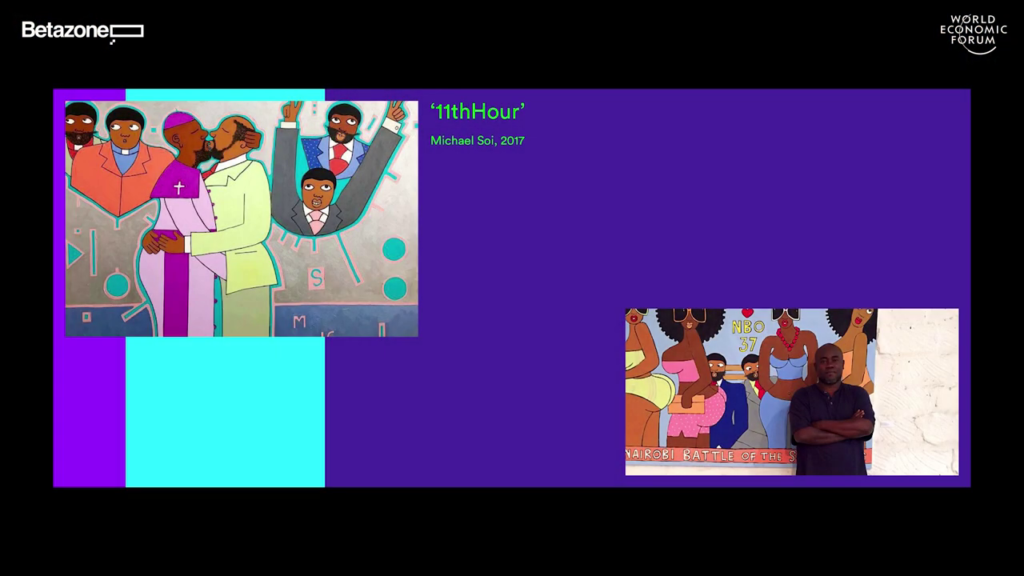

In 2017, Michael Soi as well as three other artists, were commissioned by the National Museum to create pieces of work under the label “Speaking the Unspeakable.” But when they presented their work their work was considered too unspeakable to be seen, and the work itself was banned.

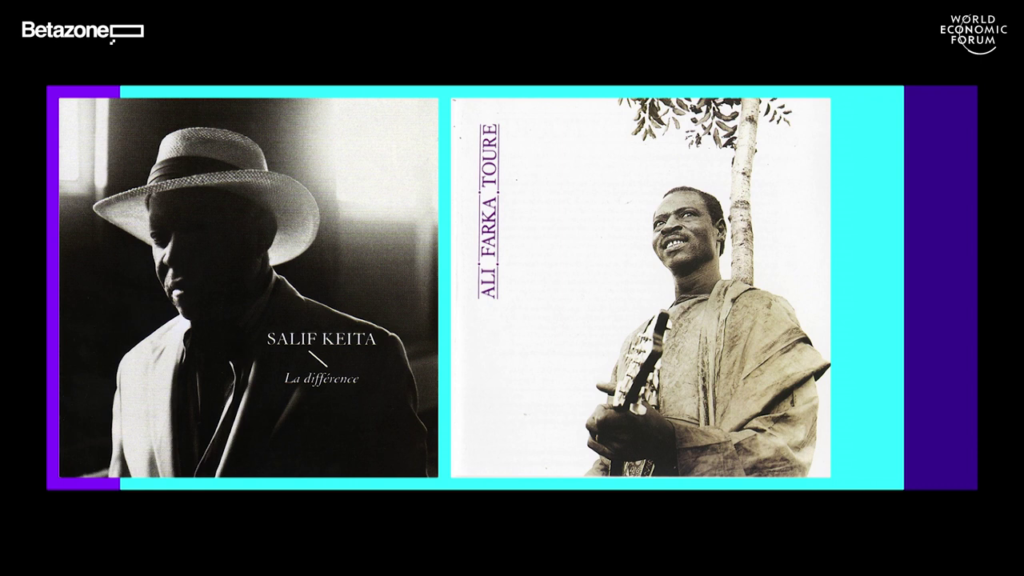

Between 2012 and 2013, for seven months, two thirds of Mali had no music, because it was banned. Now, imagine the world where Salif Keïta, and Ali Touré exist having no music from Mali, silencing the voices, silencing the art that was coming from these places, because it was not remorseful. Imagine what that does to a nation. Imagine what that does to a culture. Imagine if we did not have that music today. How would we know, how would we experience Mali? How would we experience music coming from those regions?

What I learnt as a result of this is that freedom of expression is not a luxury. It’s a freedom. Freedom of expression is not a luxury. It is a freedom.

Now, when I voted for our constitution on August 4th, 2010, I did it knowing that my rights as a woman will be protected. And I did it as an artist knowing that my rights for freedom of expression were enshrined in the constitution, our bill of rights. Among the first pages of the constitution it says Every person has an obligation to respect, uphold, and defend the Constitution.

So when our film was banned, we took the Kenya Film Classification Board to court. And we sued them for our rights to freedom of expression. We’re still in court now. But as part of the court case, we asked for the ban to be lifted for seven days so that the film could be nominated, by Kenya, as a foreign entry into the Oscars. And the judge at the time upheld our wishes, and for seven days the film was shown across Kenya.

That meant not only were we able to see ourselves as people of joy, but the LGBT people in Kenya were able to see reflections of themselves. They were able to feel valid. They were able to feel seen. They were able to have voices. But. It also meant that my family who were unable to defend me at the beginning could now see the work that I had made.

So when we speak about freedom of expression, and when we think about the work that we do as artists, one of the things that continues to remain in my head is a line from the poet Lucille Clifton. And she asks, What have you traveled towards more than your own safety?

Now, there’s artists across Africa, Stella Nyanzi for one, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o who remains in exile, there’s artists across Africa who challenge this idea of censorship. Who work hard to make sure that you get the art that you deserve. But they only do it with your support. They only do it because they know that they have a willing audience who will listen, who will pay attention.

And not only is this happening in Africa. It’s happening in Spain. It’s happening in China. It’s happening in Russia. And there’s other versions of censorship that continue to happen. In America, they have a more like…economic type of censorship. Where if you go into a studio, they can say oh, you can’t make a film with women as leads, because no one wants to see a lead as a woman. Or no one wants to see a transgender lead. Or no one wants to see a black person as a lead character.

So there’s different types of subtle censorship that continue to exist. So while we artists continue to do our part by creating, I challenge you not only to travel towards more than your own safety. But I challenge you to buy a ticket. To go out and watch work of people that you want to see. If there is a female director, and you want to see more female-directed films, buy a ticket. Do it for the data. Because this is the data that continues to feed the industries that allows us to continue to make work.

I’m not saying you have to see the film. I’m just saying you have to buy the ticket. [audience laughs] So do it for the data. And do it for us, because we are doing our part. But I challenge you to think what are you doing? What is your part towards the cause of freedom of expression? Thank you so much.