Hello, everyone. Thank you so much for inviting me here. The city is absolutely beautiful. I’m going to tell you about cyborg anthropology and the evaporation of interface. I only have a little bit of time, so I’m going to go into it pretty quickly and give some examples.

So, first off, whoever has a cellphone hold it up right now. Alright, those who held it up first are more cyborg-like than the others in the audience. In fact, we’re all cyborgs. But not the type of cyborgs that you think. We’re not Robocop or anything like that. A person called David Hess talked about the idea that we’re all low-tech cyborgs, that every time you look at a screen and you interface with something external to yourself that holds information that your eyes can interact with, you’re kind of a low-tech cyborg. Even though it’s not melded into your skull or interacting directly with your brain, it is interacting with you through an interface of your eyes or your hands, and therefore you’re a cyborg.

So, the term cyborg came from a 1960 paper on space travel. It was called an organism to which exogenous components have been added for the purpose of adapting to new ambient environments. Physically, this was talking about an astronaut in space. Because what kind of a hostile environment is space? It’s very difficult. You can’t breathe out there. So the idea of making a space suit was allowing somebody to evolve outside themselves, to adapt to this very difficult environment.

The first tools extended the capability of our fists. So, the idea of having a a hammer or a knife allowed us to have an external tooth or an external fist that we could evolve outside of ourselves, as a physical extension of self, to be much better than we could be as actual humans. But now we have these mental augmentations, allowing us to store memories on our brains and our essences in these devices.

Soon, perhaps, it will be impossible to tell where human ends and machines begins.

Maureen McHugh, China Mountain Zhang, 214.

Maureen McHugh has said soon that perhaps it may be impossible to tell where humans end and machines begin. When you look at your online profile, is that really you? It’s a representation of you that can be acted on when you’re not there. But where do you end and the machine begins? The thing is that humans and technology have coevolved with each other over time, being very very cocreative. We have survived because of technology, and technology has survived because of us.

So, a traditional anthropologist goes out to another country and looks at the natives and says, “Hmm, how interesting their cultures are. How curious their techniques. Look at these tools and these customs.” And it’s all very much that the anthropologist is an “other” person and they go back to whatever country they came from and talk to people about these interesting people. But the cyborg anthropologist looks at the the world around them and says, “How curious these people are. They have these little devices in their pockets that cry, and you have to pick them up, and you have to soothe them back to sleep. And at night you have to plug them in and take care of them. And then every two years they break down on you, so you have to get new devices.”

So, these Macy meetings started in 1941, and they were about a bunch of scientists and anthropologists coming together, realizing that technology is going to be an extremely big deal in the future. And they tried to convince a bunch of people of this. But it was very early on. Mainframe computers were barely getting a start.

Cyborg Anthropology, Gary Lee Downey, Joseph Dumit, and Sarah Williams

It took until 1992 for cyborg anthropology to be an actual subsection of the anthropology of science. So let’s talk about the present day. In the present day, we have these devices outside of ourselves, and they help us communicate with each other. But also, we’re carrying around these devices that are larger on the inside than they are on the outside. So whenever you carry around a laptop, it has all this space inside of it, and all this space connected to the cloud, and you never see it. Whenever you put a file in a system, it doesn’t make your computer heavier. Although if you put a file in a file cabinet, it would make the file cabinet much heavier.

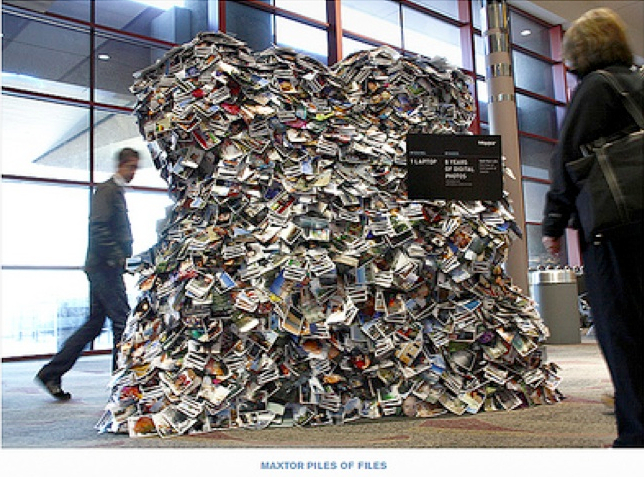

If you take your eight years of pictures that you stored up in a laptop and actually print it out, this is what it would actually look like. This was a campaign for Maxtor hard drives where they printed out eight years of somebody’s photos. Because it’s easier to put something in to a space than it is to take it out. So we’re carrying around these kind of Mary Poppins bags, where we can take anything out that we want.

So, when you start putting memories into a computer outside of yourself, you start to have these hyperlinks memories. And what happens when you have hyperlink memories is it’s not just thinking in your brain, “Oh, where did I put that memory?” and you try to think of a word to trigger the memory. You have to actually think of a word to trigger a memory. So for instance on your email account if you want to find an email, you have to actually type that word instead of just think about it in your brain.

And that makes us into these kind of persistent paleontologists, digging through all of our old data trying to find out the thing that we left there that’s been buried by hundreds and hundreds of emails. So we’re all becoming these kind of paleontological machines that are going out and digging through everything all the time. And if there’s too much of that and too much sediment gets laid down and too many emails, we start to have these kind of panic attacks. There’s too many emails, there’s too much information coming in.

This brings me to the idea of prosthetics and their discontents. We have all these external prosthetic devices. And actually Freud this book called Civilization and its Discontents, and he warned of this future in which we would have ill-fitting prosthetics that were pretty good, but they weren’t all-the-time good. And so we kind of as humans live in this mild dystopia. It’s not a complete dystopia world because if it was we’d get very angry and revolt. But it’s just mild enough that we have some complaints. So, whenever you have a device and it freezes up on you. You know, your external bring freezing up on you. It’s a big problem.

One of the other problems is that your external brains last much shorter than your actual brain does. So, it would last only for two years and then you have to throw it out. And it makes big piles of junk. I mean, humans are very curious creatures. They have all these external objects then they shed them just like leaves of trees. But when a tree sheds its leaves, it makes room for new trees. When we shed our technology, it makes room for more technology.

And the planet also has a bunch of junk around it. There’s about eight thousand satellites up there that you can see on Google Earth. And only six hundred of them are currently working. But these allow us to connect to each other and talk to each other. So even our own planet has become a cyborg.

The other thing is that humans tend to make these kind of snail-like creatures that they drive in, and they’re completely disconnected from each other when they’re driving down the road. They’re kind of like spaceships. You can’t actually walk on a highway because you’d get run over by a car. It’s only for kind of advanced cyborgs that want to extend themselves and go very fast. But the problem is that when we’re stuck in cars we’re kind of on pause. We’re machines, and we’re not able to talk to each other even though we’re having the same annoying experience of being in traffic.

So when the cell phone came out, it started connecting people in these isolated environments. It started giving people something to do when they were on pause, when they were hanging out in airports, when they were hanging in these non-spaces where there were no friends and no family, where they kind of felt like machines. In a way, it allowed them to be more human.

So, there’s this idea of ambient intimacy that it’s not that you’re connected to everything all the time, but you always have the ability to connect to someone. And if you were to look at all the people in your phone right now, it would probably look like this. All the people that you have access to right now in the tiny machine that you hold in your hand via email, via Twitter, via Facebook, via any of the other social networks that you have via your phone. It’s like a tiny village in your pocket that you’re carrying around all the time. And even if you’re in an isolated place you can suddenly reach out and have contact with somebody.

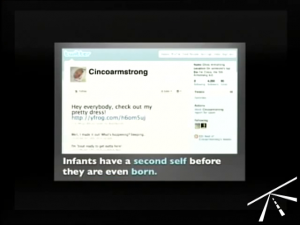

So let’s go into becoming a cyborg. Now kids have a kind of second self before they’re even born, that they learn to deal with. But this self becomes more important than your DNA. So people are going to grow up in this world where this can act for you when you’re not even there. People can click on you, your secondary self, your online presence, without you being there. So you have this ability to construct whatever you want it to be.

Just as you have to wash your hair in the morning and look presentable, you have to do the same thing with your digital self. There’s a lot of people who forget to update their online status, and they feel guilty about it. And they say say, “Oh no, my status is old.” And they keep worrying about their online presence and what it looks like. And this is going to become increasingly important, your your presentation of self in digital life.

So, as you become more of cyborg, the the delineations between work and play become more difficult to define. Reality is not always fun. You have to wait in line, and you have to wait in traffic. You’re put on hold a lot. You’re doing these very annoying things that humans shouldn’t be doing, and sitting there in environments in which humans shouldn’t really be in. But suddenly there’s this layer on top of reality, where you can check in and you get a few points. And you can rate reality. And you can make it so that you can have a good experience next time.

And the other thing is that you get accelerated rewards. Say you get four years in college and you get out. And your reward is graduation. Say you know you want a promotion and it takes you six months to a year to get a promotion. If you play Farmville and you click on something, you get an immediate reward. You get either some sort of point bonus, or something that makes you feel like there’s an interaction. And for a lot of people, the rewards in real life are slower than the ones online. So they’re more attracted to these interfaces. And the other thing is, if you’re living in a small apartment and you don’t have much room to do something, you can be powerful in these environments and actually do something. It’s kind of a freeing thing to do.

So basically, these are kind of database games. Foursquare is not an app, it’s a data entry game where you’re entering place data and you’re marking territory, just like a dog going to a street corner and marking their territory. And then the other dogs can see where they are and whoever’s the top dog. So, if you check in on Foursquare enough, you become the top dog as well. It’s a very basic, animalistic game. But the whole time, this free service is collecting data about places. It’s become one of the most powerful place databases because it’s put this little layer on top of reality and made it fun to do data entry. And now people are just doing data entry all day for Foursquare for free.

It’s the same thing with Facebook. Facebook is basically a spreadsheet game. Spreadsheets have never been so interesting. You log on and it tells you what happened in column A2 and cell 4B. And then you change cell 3, and then it gives you points. And then somebody says, “Oh, I really liked that,” and suddenly you have this psychological feeling that you’re actually worth something. And you know, it’s not that you would have fifteen minutes of fame in your lifetime, but fifteen minutes of fame every day. You have to keep getting that in order to feel human and connected.

So social grooming becomes this very important aspect of it, that when you post something you expect a response. And you expect to be interacted with. And if you don’t it feels physiologically bad. And because our brains are very good at not being on to these external spaces, we can actually feel these psychological and physiological effects when we’re dealing with these virtual spaces. This is virtual reality. It’s two dimensions. But it’s just as good as having a three-dimensional virtual reality with its effects on your brain. So work is just badly-designed game play. And I think that in the future, work and play will begin to merge more and more and more.

So let’s talk about the future very quick. What will happen in future? Well, Mark Weiser at PARC Research came up with this term called “calm technology.” And the idea behind calm technology is it gets out of the way when you don’t need it. And when you need it, it comes back into play. And the other thing is that actions, just your everyday life moving around, will trigger events. And basically these invisible interfaces will allow you to just do something and something else will be triggered instead of having to physically press a button or mouse over to something and click on it. Just you living will cause these events to happen.

Here’s an example of calm technology. When you go to the tap and you get a glass of water, it will show you what temperature the water is so you don’t have to put your hand under it and get burnt or feel that it’s cold. And it only turns a color when you’re actually using the faucet. So it’s actually a very useful piece of technology. So this is an example of some calm technology.

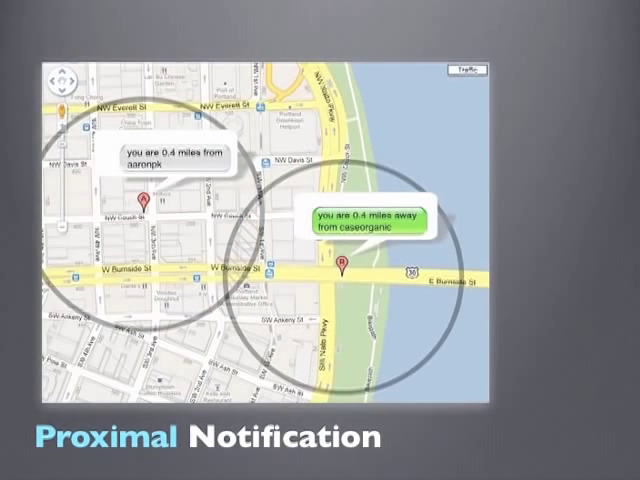

So information should be pushed to you. You shouldn’t have to go out and get it. The idea behind this is that when you get to an airport and you need an address of the place you’re staying, it should come up and be pushed you just on your device. You shouldn’t have to be a digital paleontologist and go and dig for it under the fifty other emails that you got. It should know where you are, what you’re doing, and then push that information to you. The idea is that the robots on the other side are doing what machines do best, leaving you to be a human and do what you do best.

So ambient user input is a way to do this, based on your location, based on your location history, do you drive or walk more often, based on the time of day, based on the prior actions or whatever you do on a network, can determine what to send to you. Also, instead of waiting for somebody at the corner of the street when they’re going to pick you up you should be able to see them in real-time arrive on your phone. Because there’s all this uncertainty around the simplest of things, which is meeting somebody. You don’t want to just wait for somebody for twenty minutes. But if you knew where they were, you wouldn’t have to text back and forth saying, “I’m going to be late. I’m on my way. Oh no, I got stuck in traffic. Oh, I just left my house. Oh, I’m five minutes away.” Because by the time that happened, somebody’s around the block getting a bagel or something.

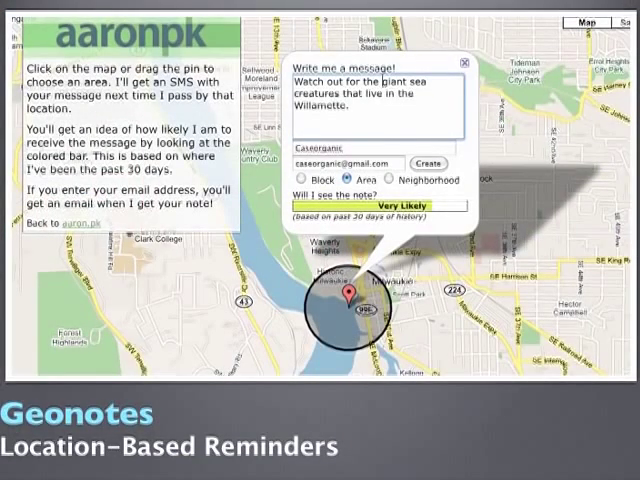

Also, geonotes, the idea of a location-based reminder. That you can leave your grocery list at the store and forget about it, and when you get to the grocery store again get that list sent to you. Something as simple as that in everyday life, just getting helped out by technology so you can store it and forget it. Your brain doesn’t have very good… It doesn’t float contextual memory. It doesn’t say, “Okay, I remember that I need batteries now,” because when you get to the store, you need milk and you forgot the batteries. And you get home, your flashlight never works, you never get the batteries that you need. So leaving something in a location allows you to leave a message to your future self.

The idea is that your mobile phone is not really a phone, it’s set of sensors. And these sensors are a miniature wearable computer that you have with you all yet all the time. And there’s a server up there that can compute things for you and send back information to you. It has GPS and knows the time of day, it knows how fast you’re going. And this should be able to compute things for you, and become effectively a remote control for reality.

So for instance, I have this setup in my house. When I get home, it automatically checks me into my house because it knows that I’m home, and then it triggers the lights to turn on. And then when I leave, it triggers the lights to turn off. And I never had to press a button the entire time. Just me being there has triggered an invisible button. So I didn’t have to press anything, I didn’t have to turn on the lights or remember to turn off the lights. And that’s one action I don’t have to remember anymore. And that’s something that that frees up my mind to think about other things for a few seconds a day.

So the best technology is invisible. It just gets out of the way, lets you live your life. And so the idea behind interfaces is the first interface was these big buttons. And if you wanted the buttons to do something different, you’d have to physically rewire the entire device. But, when the interface became liquid on a screen, you could use software to reprogram those buttons. So it goes from solid to liquid to air. So the next interface revolution is this…air…just doing things and having things happen. Which is the idea behind ubiquitous computing, which is finally capable of being done because we have the Internet and we have this whole database out there that allows us to compute in the air and sent it to devices all over the place.

So the idea behind cyborg anthropology is to look at what’s going on in the world, step outside of culture, and see what’s actually happening with these weird devices in everyone’s pockets, and see how that affects culture. Thank you very much.