Ethan Zuckerman: So, this is the moment in the program where we have a seamless transition from one tricky topic to another tricky topic. In this particular case, we’re transitioning from the idea of research that in many cases makes us deeply uncomfortable, research that in many cases we haven’t been able to take on for a complicated wealth of ethical reasons, social reasons, as well as legal reasons. We now have a panel which is looking primarily at legal barriers to research. And this is a panel that really asks the question, why can’t we do that? Why aren’t we allowed to take on certain particularly pressing research questions?

To moderate this panel, we have someone who over the last five years I have heard dozens of times, “Why can’t we do that?” because he is my doctoral student, Nathan Matias, who is doing absolutely groundbreaking work around questions of discrimination, harassment, and online behaviors that are dangerous and detrimental to communities, and helping communities try to figure out how to find their way through it.

So I’m very very happy to hand you over to Nathan Matias who’s going to lead us through this next set of the conversation. He in turn is looking for something that could advance slides, and I will hand it to him and hand the stage to him at the same time.

J. Nathan Matias: Thank you very much, Ethan. As Ethan said, quite often when we’re asking these difficult questions we’re asking about questions where we might not even know how to ask where the line is. But in other cases, when researchers work to advance public knowledge, even on uncontroversial topics, we can still find ourselves forbidden from doing the research or disseminating the research. Especially at moments when the research we’re doing, or the work of spreading it, comes into tension with the businesses who are involved in the issues we study, and in the very work of sharing knowledge. At such moments, we can find ourselves tied to the mast, not as Cory Doctorow said earlier today, of our principles, but tied to the mast of laws that have been set up to protect those interests and which can get in the way of important work and public knowledge.

Here today, we’re going to be hearing from speakers who have done work that touches up against laws related to cybercrime, and laws related to copyright. In the areas of cybercrime we have laws like the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, which while it was designed to help people and companies be protected against certain kinds of unlawful access to computers, has also turned out to be a powerful protection against accountability as researchers try to understand the power of AI and the impact that machine learning can have, not just on our everyday lives but also on fundamental principles and values of equality, fairness, and discrimination.

And even when we’ve produced that knowledge, when we’ve completed our research, when we’ve published it, we can discover that not everyone is able to access that research. That when we do work in the public interest, when we add to knowledge, often the people who are most able to access it are the people with the most resources, the people and the institutions who are able to pay. At those moments, we basically have three choices.

Our first option is to just give up and walk away from the challenge of advancing public knowledge. Our second option—which is what many of us do—is to disobey quietly, to disregard the rules and hope that we won’t get caught, in lots of small and everyday ways. And it takes great courage to see the third option, which is to try to solve the issue, not just for ourselves but for whole fields and societies. And I’m excited today that we’re going to be hearing from two researchers who have done remarkable work to do just that.

Firstly we’ll be hearing from Dr. Karrie Karahalios, a professor of computer science at the University of Illinois. Karrie has been a pioneering researcher of ways that social technology is shaping our lives as societies, designing systems and helping expand our theories to understand our relationship to each other and how that’s mediated through social networks, through communication technologies. She’s also an expert on algorithmic accountability, and a leader in early-stage efforts across academia to understand the role that machine learning systems are playing in our everyday social lives. Just three weeks ago she joined together with researchers at the University of Michigan, Northeastern University, First Look Media, and the American Civil Liberties Union to file a lawsuit aimed at clarifying whether researchers should or could be able to do important research to understand algorithmic accountability and discrimination.

After Karrie, we’re going to be hearing from Alexandra, who is a Kazakhstani researcher who’s studied everything from neuroscience, computer science, to history of science, and is most well-known for her work on a system called Sci-Hub, which provides over fifty-one million scholarly articles online for free by pooling the access credentials of academics from many universities and making those articles available freely to download.

As we think about the work that Karrie has been doing to better study the impact of social technologies and algorithms on our lives, and the legal our legal boundaries that forbid that work, and as we think about the legal challenges that make it difficult for everyone to access precious knowledge coming out of research, we’ll also be having a conversation about the challenges of making that step to try to solve a wider problem for a wider field and community, as well as those tensions we find ourselves in with business and with law, at the boundaries of law and research. Karrie. Please welcome Karrie.

Karrie Karahalios: Oh, we have Alexandra.

Matias: We were having difficulties with Alexandra joining us. It now looks like those have been resolved. So actually, let me ask you to please welcome Alexandra Elbakyan to share her work with us.

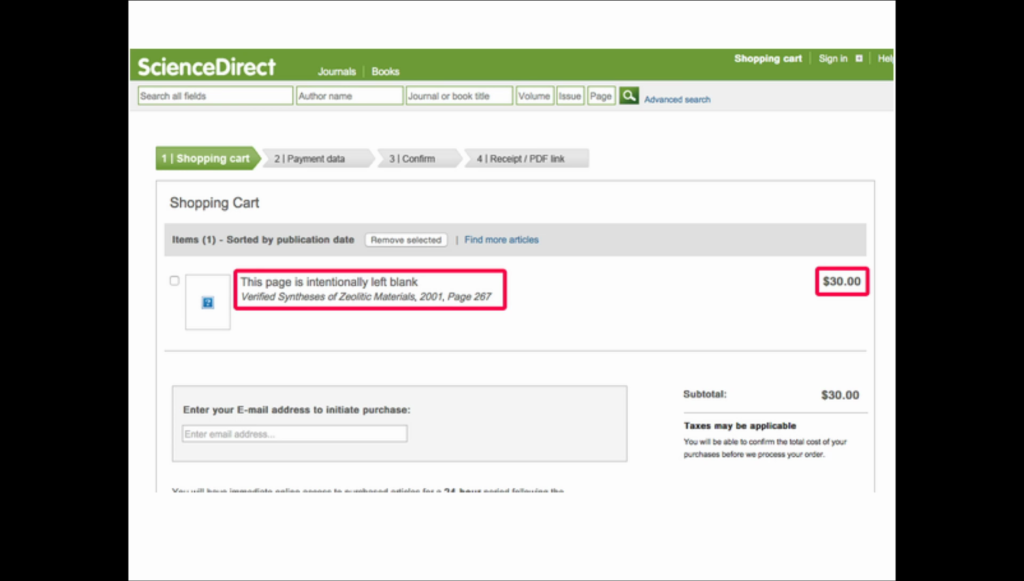

Alexandra Elbakyan: Okay, so Sci-Hub. Let me start with a problem. So the problem of dissemination of research results, today it’s very limited because prices to read research papers are very high. So these prices render the research papers to be inaccessible by individual readers and even those people who normally should have access to research papers such as scientists, students, and medical doctors, they also don’t have access.

So I created Sci-Hub, a web site where you can get these papers for no payment. And [?] is only problem. So, web sites like Sci-Hub, they are currently prohibited by government, and that means operation of such web sites is currently not lawful because research papers are considered to be some kind of private property, and hence the free dissemination of them can considered as some kind of theft.

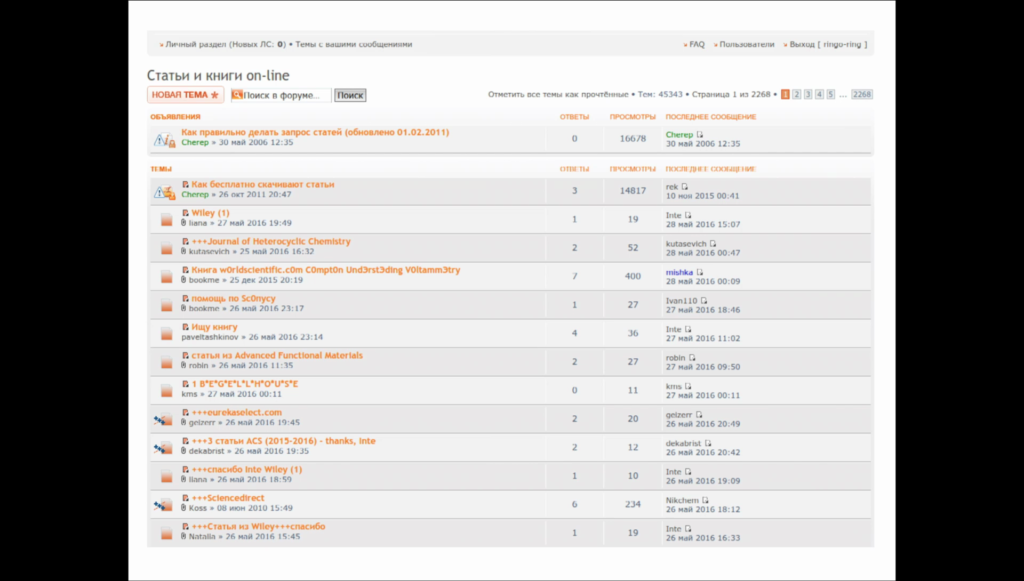

So let me look at something about the pre-history of the web site. Yes, I myself experienced a problem while working on my research projects in Kazakhstan, and I searched online and I found many places where people helped each other get literature and circumvent firewalls. And many such places were in English and Russian. For example, you can see on the slide such a forum in Russian.

So, in 2009 I became a member of the neuroscience.ru online forum. And this forum had a separate topic where everyone asked about how to get such and such paper, and other people who had access, they helped. So I got an idea to make this more automatic and more convenient. For example, you could automatically send uploaded papers to email. So I asked the forum administrator to join the team of developers, but he was not very fond of the idea, and particularly because of corporate law.

In 2011 I became a member of another research forum, and they had implemented what I was thinking about two years ago. So they had research papers automatically uploaded to the forum and sent to emails. So there were some kind of very elaborate rules developed, and also there was a system implemented in Perl. But the main developer abandoned the system, so when I found it it was basically barely working.

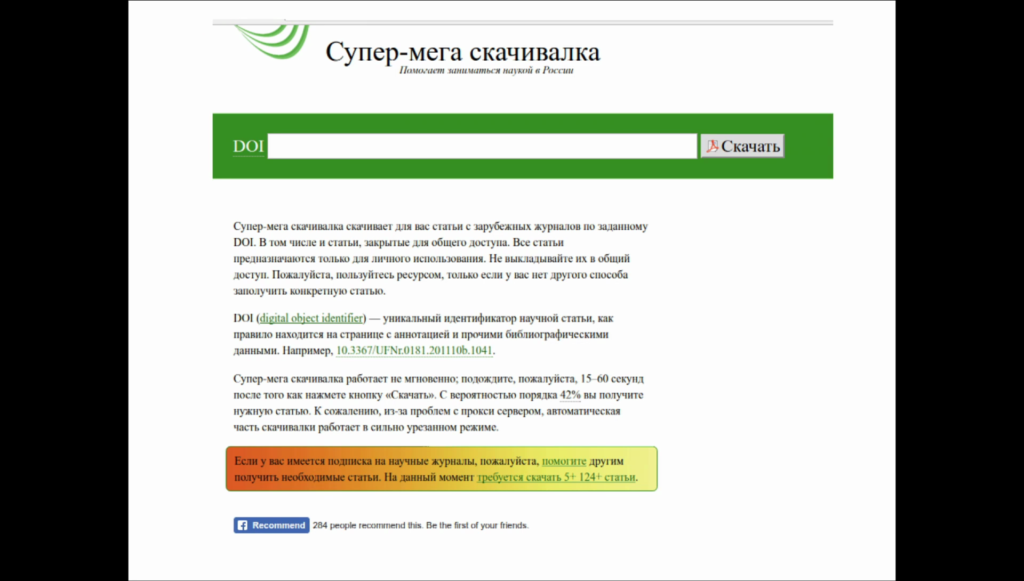

This is another project of that kind. It’s called Супер-мега скацивалка, or “Super-mega download” in English. It was created by students of one big Russian university. Here you could put in a DOI and it would be downloaded using university access and give out a PDF directly. Here the developer says that it was successful for 41% of requested papers. It was a closed and non-public project, and to access it you needed to complete a Russian [problem?]. So only people from Russian roots could access it.

So in 2011 I created Sci-Hub. The first iteration was drafted in a couple of days. What I did was I took open source software that was created to circumvent ordinary web site blocks and then modified it to work with universities. So if not for open source, I would not be able to implement the idea quickly. And what Sci-Hub did was allowed users to browse research web sites as if they were browsing from university computers, and hence they could download via university subscription. And at first Sci-Hub didn’t rely on any CrossRef DOI.

A few months later, I was contacted by Library Genesis admins, and they’d just created a section on their web site to store research papers and had started uploading some papers there, but not in very big amounts.

At first Sci-Hub was used primarily by former Soviet Union countries, and I blocked access for the United States and some of Europe, to keep the project safe. After one year of [?], people in China and Iran became aware of the project. And then traffic became so high that our university access started being blocked. So I had to block China and Iran from the web site, too. But now all these countries are unlocked and working.

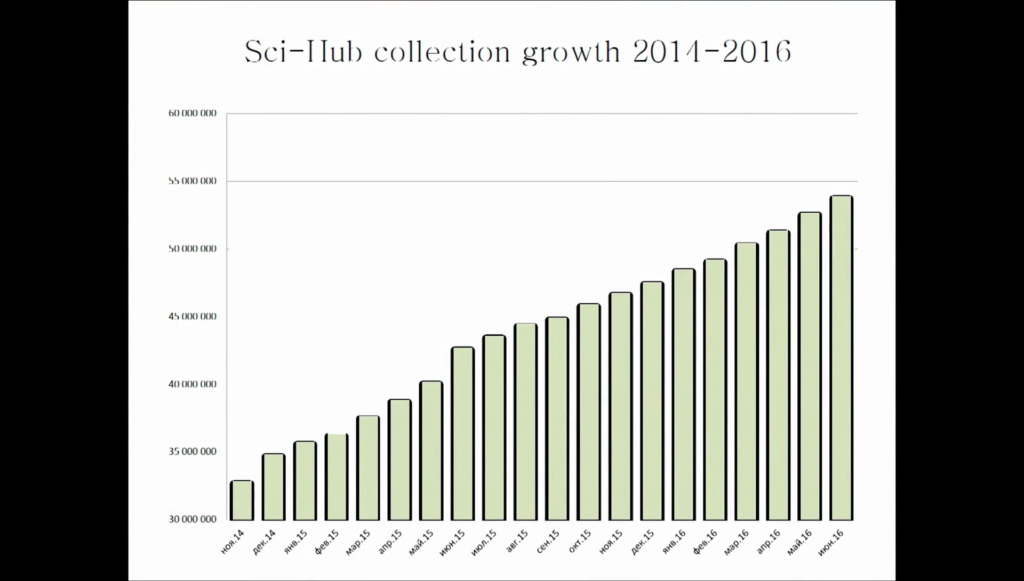

So in 2014 I started to proactively download papers from research web sites and upload them to Library Genesis’ collection and to Sci-Hub’s own storage. So by that time, the project got its own storage. Well, once a paper is downloaded once it’s basically free and you don’t need to download it again. So for major publishers now, we have more than 90% of papers freed, and so technically the problem of paywalls is solved. So what is left is to make all this legal.

…the professed aim of all scientific work is to unravel the secrets of nature

James Clerk Maxwell [presentation slide]

So why does science have to be open? There are many reasons, but what is most important is that the nature of science is about discovering secrets and not about keeping them.

And when science is open, how can it benefit research? Let’s see. Today’s system makes science be concentrated in big organizations, so that small companies and individuals simply cannot have subscriptions, and that means they cannot make creative contributions. The research is concentrated in big institutions, and these institutions tend to comply to standards. And hence science became standardized and new ideas cannot develop. So once science is open, perhaps there will be big progress forward. Okay. Done.

Matias: Thank you, Alexandra. Next we’ll hear from Karrie, then we’ll have a conversation before opening it up to the floor. Please welcome Karrie Karahalios.

Karrie Karahalios: So, I’m going to talk about the need for auditing algorithms. A lot of this work started for me around 2011, 2012, along with colleagues Christian Sandvig, Kevin Hamilton, and Cedric Langbort when we founded the Center for People & Infrastructures. And we decided we really really wanted to investigate the algorithms that shape people’s lives and sociotechnical systems.

One of our first projects was a case study looking at a surveillance system with cameras in Europe on a train station. And one of the things we encountered was difficulties like imagine a system with machine learning where an operator might always stop and pause the camera looking at a specific type of person, whether they be black or white. In this case we were worried that they might always stop when somebody was black. What happens when a system learns this and takes bias and builds it into a machine learning algorithm from training data and keeps growing? In contrast, this is a case where people really worried that people that were black would quickly be observed.

In almost reality, what we started seeing was infrastructures and systems where people black people weren’t seen at all. So I don’t know if you remember this case. Desi and Wanda made a YouTube video where they’re looking at a new HP camera that was created. And it turns out that this camera was supposed to track people. And it tracked Wanda perfectly. Wanda would go to the left, she would go to the right, she would zoom in and she would zoom out. The camera did a beautiful job. Desi, who happened to be black, would go in, move around, jump, move back and forth; absolutely nothing would happen. He went so far as to claim facetiously that HP Hewlett cameras were racist. He said this in a very very humorous tone, but they touched on a really big important problem.

Another case that happened here in Boston was with Street Bump, July 2012. This was an interesting system that was released. You had smartphones in cars and taxis. And with the accelerometers on these phones, you can tell where there are potholes. This was lauded as a huge huge crowdsourcing success, and it was in many ways.

In 2014 it was revealed, though, that some poor parts of Boston were not serviced by this, and potholes were only getting fixed in rich, wealthy suburbs, and not in some of the poor neighborhoods. What was really great about this information coming out was that the problem was solved. They said they fixed it. I don’t know how they fixed it, but they said they fixed it.

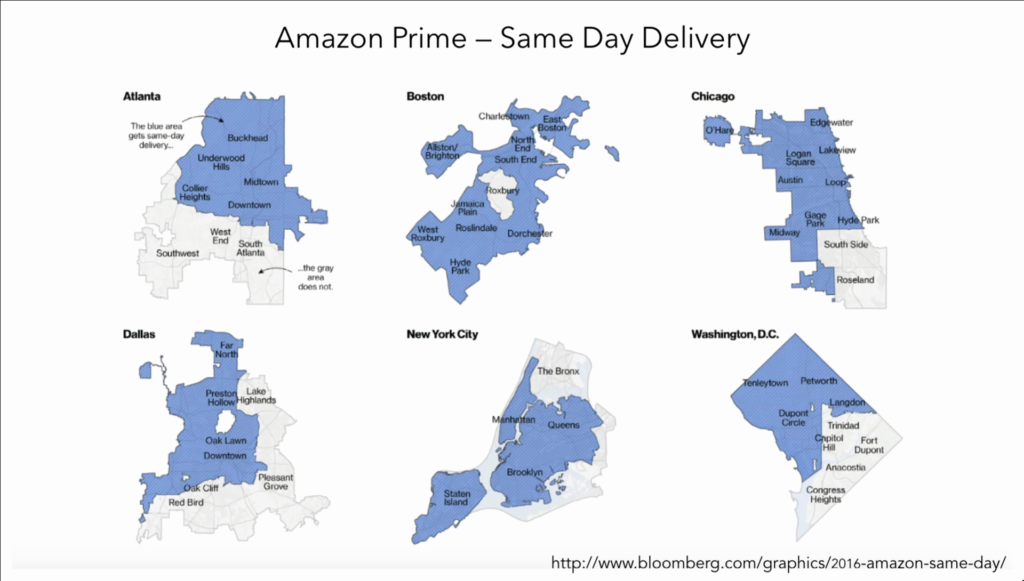

Image: Bloomberg, “Amazon Doesn’t Consider the Race of Its Customers. Should It?”

Another case, much more recent, 2016, Amazon Prime same-day delivery. One of the most stark examples here again is in Boston when you look here, Roxbury, pretty much all parts of Boston are getting same-day delivery from Amazon Prime. Roxbury is not. Same thing happened in a bunch of cities. When this information was revealed and made available to the public, and also made clear to Amazon that it was unacceptable, immediately this was remedied in Boston, New York City, and Chicago. Hopefully it’ll be remedied across the country. But this information needs to get out there for change to happen.

Something else you’ve probably seen very recently around the same time in the newspapers, predictive policing. Again this needs to be audited. We need to see if there’s bias in who’s being predictively observed, who’s being maybe stopped by police, or what zones are being productively observed. Are they poor areas, are the wealthier areas?

And probably even most recently in terms of the game Pokémon Go why is it that there are fewer Pokémon stops in poor neighborhoods, and so many in rich, wealthy areas? There’s lots of reasons for this, and again crowdsourcing plays a role here. We need to think about the bigger consequences. What happens so we have self-driving cars and the car has to make a decision about whether the owner of the car dies, the person on that corner, or the person on that corner? How do we make sure we look at these algorithms and objectively audit them so that we can then find solutions for them?

So in that vein we decided with our center to explore fair housing. Are racial minorities less likely to find housing via algorithmic matching systems? And there’s an interesting study done by Edelman where he found that if you are black and you were renting an apartment on Airbnb, you will get less money for your unit than somebody who was a white that had a similar unit that was controlled for price and location. Does this work both ways?

So it turns out that in looking at this work, there is a precedent and full support for auditing for housing. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 decreed that race simply could not be considered in some situations. The Fair Housing Act, ’68, said that you could not discriminate based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. Took twenty years later, unfortunately, to add disability and familial status. I say unfortunately because it took too long. And again later in 1987, the Housing and Community Development Act declared that the Department of Housing and Urban [Development] can enforce the FHA. And specifically, on top of that, it can build special projects, including development of prototypes to respond to new or sophisticated forms of discrimination against persons protected.

So, how did they do this? They did what’s called a traditional audit today. They would pair two people together, let’s say one white person, one minority. They would match them on family and economic features. They would have them successively visit realtors, and then they would record the outcomes, what happened.

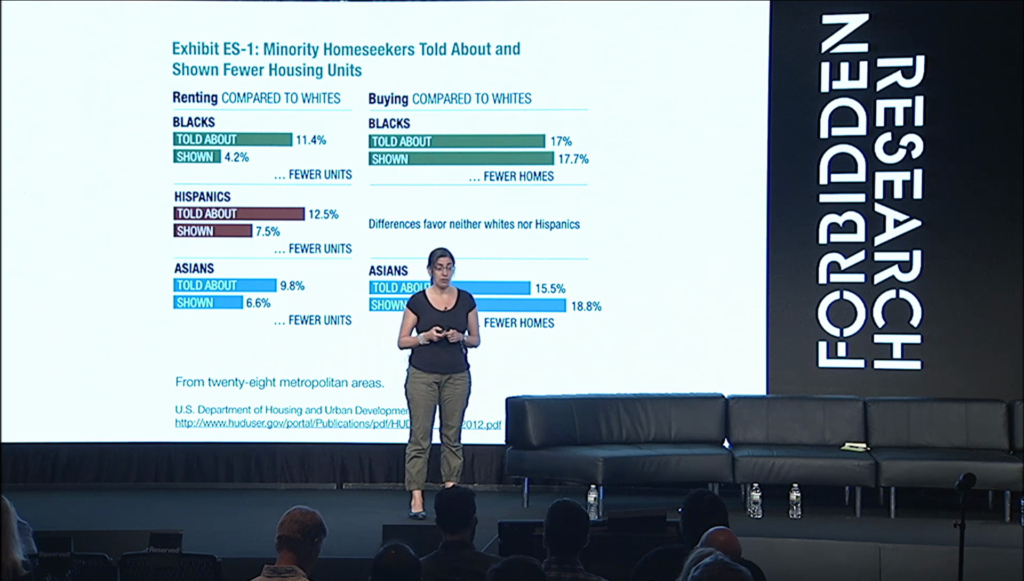

US Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Housing Discrimination Against Racial and Ethnic Minorities 2012” [chart appears on page 11]

The first one of these paired testing experiments happened in 1977. The most recent one happened in 2012. And one of the things that they found was that blacks, Hispanics, and Asians were told about fewer units than white people. Since then we’ve had lots and lots of online systems that find housing for us. There’s Zillow, there’s Trulia, there’s homes.com. So many of them I can’t even begin to list them all in this ten-minute session. But we wanted to explore what happens on these online sites with these sociotechnical systems that might have crowdsourcing implications as well.

So we wrote this paper about auditing algorithms, and methodologies for doing so. And we tried to apply this for fair housing. The first methodology we came up with was getting the code. But this can be really wicked hard. People don’t want to give you their code; we’ve tried. That said, even if you were to get it, it would be really hard to make sense of it sometimes.

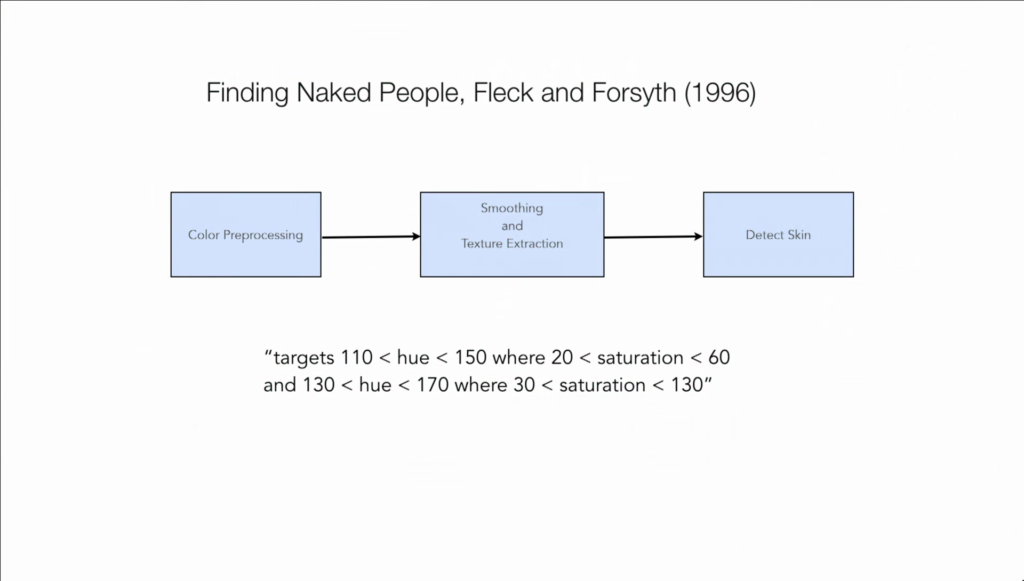

But researchers were very willing to give us their code. This was a very famous paper in 1996 by David Forsyth and Margaret Fleck. They gladly gave us the code immediately. And they became famous writing an algorithm called Finding Naked People. And if you look at the code, there’s actually lines of code in here that they told me they actually had to add a line of code because their finding naked people algorithms did not find black people. They actually had to go in there and make it find more people. Some might argue that the act of doing this actually causes ethical concerns, and I’m not going to get into that here. But getting the code is hard, and making sense of the code is hard.

Another option is to ask the users. And we’ve done this a lot with our own work. In housing, it’s very hard to get a large group of people, a good sample, to actually go and look for housing for you and to do this on the scale—nationally, in the hundreds of thousands. We’ve done this in the field of algorithmic awareness, and I can tell you that we faced many many challenges doing this. It took us over a year and a half to get a non-probability sample, which even that is not ideal.

Another approach is to collect data manually. And that is also extremely difficult. In the case of housing it may even be impossible to find this housing data online, because people aren’t going to provide it. We’ve tried having people crowdsource it using Mechanical Turk and similar systems. Not only is it not reliable, but people do not provide it.

Latanya Sweeney, however, did an amazing study where she looked at searches for people online. She did this manually, I want to add. So she would put names of white people, and she would say, “Look, Carrie Swigart: found.” You put in the name of somebody who happens to not be white, and it says “Keisha Bentley: arrested” as opposed to being found. She did this with a thousand people manually, by hand. And one of the things we’re going to see a bit later is how this might even be a violation of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, doing this manually and some sites.

You can scrape everything. Again, this is a violation of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act. But we’re all— I don’t say we’re all doing this. Many researchers are doing this today. I mean, people are scraping left and right. And it’s something that you see in hackathons every day. It’s something that you see in computer science classes. It’s something you see in data mining. And it’s something predominant in conferences like KDD, dub dub dub, CIKM, and so forth.

Our study with bias in social media feeds came to an end in April of 2015 because the API was deprecated. So we had the option to scrape there. We chose not to, because we wanted to maintain a good relationship with Facebook. We decided that the project could come to a reasonable end and we could work on other things. But we could have continued the exact same work if we’d scraped the site. The interface would look almost identical. We had lots of people in computer science departments using our tool. Lots of people using our tool in art and design departments internationally. But we shut it down. And we intentionally shut it down because of the terms of service.

And last but not least—actually it’s the second to last, but not least—sock puppets. Sock puppets, as you might imagine, is an approach where you create fake identities and you put them into a system and see what outcomes you get from these multiple sock puppets. So you might make an account for somebody and say this person is a female who’s 46, white, makes this much income. Make other account and say this person is black, 45, makes this much income. And then let these little bots loose on the Internet and see what happens and measure the differences that you get in terms of advertisements, in terms of housing, and so forth.

This approach can work really really really well. Christo Wilson and his colleagues have used this very very well to find price discrimination. So they found, for example, that if you buy things on your mobile phone it costs more than if you buy it using a desktop. He’s found that there’s price steering happening from the cookies that you leave on your computer. Sometimes the more times you go to a site, it might be more expensive than just clearing everything and starting from scratch. What they did is they made three hundred sock puppets, but it wasn’t enough to get the work done— I’m sorry, they used three hundred real people, and made additional thousands of sock puppets to actually find statistical, meaningful data.

And finally, you could do a collective audit. And this is hard and this would be a dream, but I pose this as something that we should all strive for in the future, where you get lots of people working together to provide common information to be able to do this type of audit that we talk about.

So, we got really really excited when this paper was cited by a White House report on big data. They named five national priorities that were essential for the development of big data technologies. And one of them was algorithm auditing. Among some of the others, included the right to appeal an algorithmic decision, ethical councils, and clear transparency in how you create algorithms. Very specifically, what they said about audits is that they wanted to “promote academic research and industry development of algorithmic auditing and external testing of big data systems to ensure that people are being treated fairly.” And we got super excited and were like this is great, let’s get to work.

And there was one block, and that’s the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act. This was founded in 1986. Some say it was a response to the movie WarGames which came out just a few years before. And at the time it was a very different environment than the environment we’re living in today. Keep in mind that we didn’t have web browsers at the time, most people did not have broadband or even access to email.

And so as a response to this, to continue our work and to continue it without ambiguity in the law, to continue with informality, with the ACLU and colleagues we sued the US government. And this happened, like Nathan said, just a few weeks ago and we’re waiting now to get a response from the government to see what happens.

Specifically, the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act says that it prohibits unauthorized access to a protected computer. And a protected computer implies any government computer, any interstate or international foreign commerce or communication system. It also includes any web site accessible on the Internet. Even the term “protected computer” can be ambiguous for many. The thing that is most confusing is the term that you “exceed unauthorized access.” And this is specifically the point they we’re targeting in the lawsuit. In this case, many many courts to date have repeatedly asserted that violating terms of service exceeds authorized access.

So the first violation of this is a one-year maximum prison sentence and a fine. Subsequent violations result in a prison sentence of up to ten years and a fine. Unfortunately, there’s no requirement of intent to cause harm, or actual harm stemming from the prohibited conduct. And so your intentions here don’t really play a role. This echoes what Cory was saying earlier this morning with DMCA.

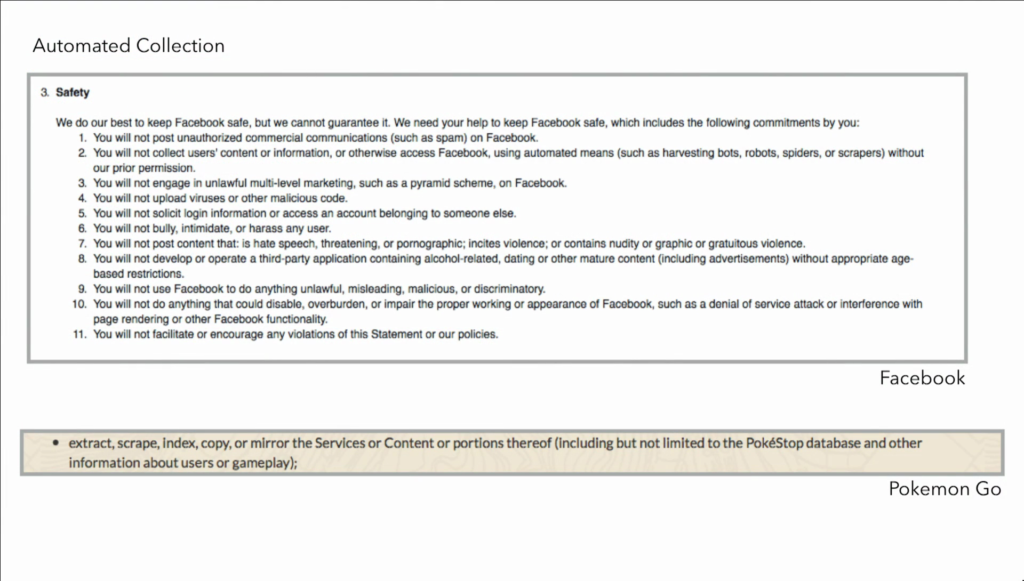

And so terms of service, like why is this such a big deal? And I may be overstepping my bounds here, but I imagine many of us are violating terms of service every day without even realizing it. So, some of that the obvious things from terms of service, no automated collection. The top here is from Facebook. It says you cannot use automated means such as harvesting bots, robots, spiders, or scrapers, etc. On the bottom we’ve got Pokémon Go. Essentially the same thing, including but not limited to the PokéStop database and other information about users and gameplay.

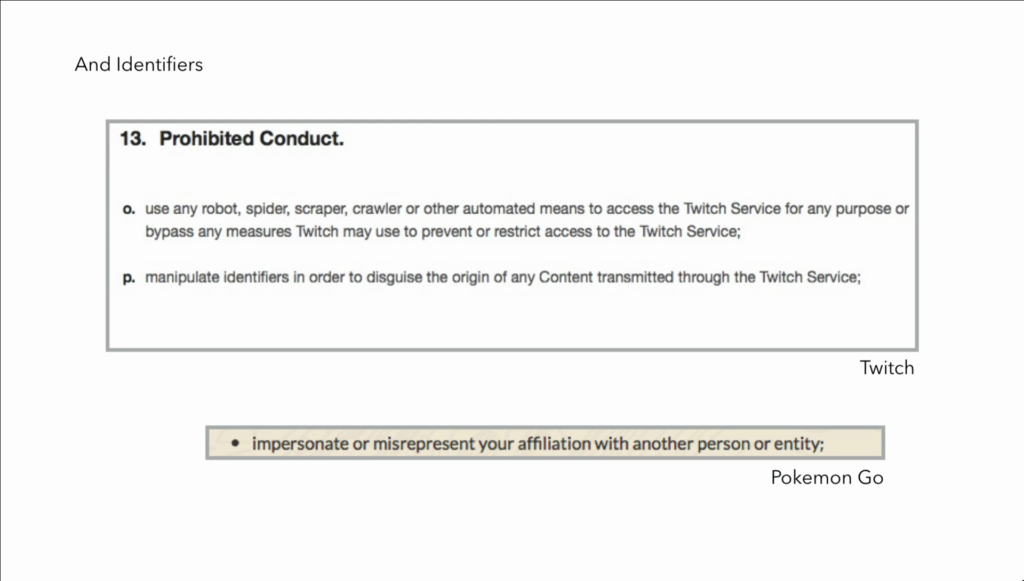

In addition to automated collection, they don’t want you to be able to create these sock puppets that we talk about. So you can’t manipulate identifiers to disguise the origin of any content transmitted through the Twitch service. So if you want to do something a regional, you can’t do that. You can’t impersonate or misrepresent your affiliation with another person or entity.

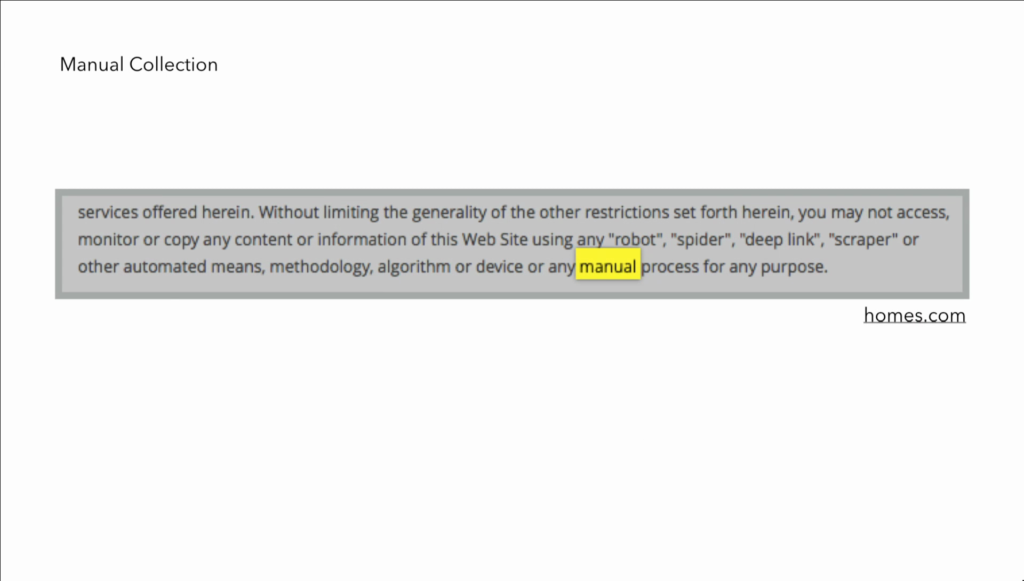

Even more confusing is in this case specifically they banned manual collection of data. So here, again the spider, the deep link, no scrapers or other automated means, methodology, algorithm or device or manual process for any purpose. I don’t even know what that means. I can’t begin to explain that. But one might interpret this as just sitting down in front of a computer, taking a pen and paper and just writing something down, and that would be a violation.

Some other things that you cannot do, reverse engineering. Bunnie talked about that earlier this morning. And one of the other reasons why this makes this so frustrating is because terms of service are not static. For example this company, “FrontApp reserves the right to update and modify the Terms of Use at any time without notice.” So just by going to that website, you agree to the terms of service.

Again, and I apologize for the many Pokémon Go references, in this case unless you opt out, you basically give up your right to trial by jury or to participate as a plaintiff or a class member in any purported class action or representative proceeding with the site. Just by going to this. And who knows to opt out, because how many of you have ever read the terms of service before you’ve played Pokémon Go?

So, why is this so important? Researchers, journalists, everybody, essentially, is affected by this. As an instructor, as a lecturer, as a professor, I care a lot about protecting my students, in classes, hackathons, doing research. Violating terms of service in many cases can lead to unpublishable work. You can spend years and years on a dissertation and possibly not be able to publish it. There’s inconsistencies in who publishes, who doesn’t. Or who allows one person to publish and doesn’t allow somebody else to publish with same methodologies. IRB may not approve of your work. Your reputation could be at stake. Finding employment; let’s say you want to work at Facebook, but something gets in the way maybe because of a study that you did. Research funding, that comes up a lot so I won’t belabor that point.

But I do want to start briefly talking about the importance of norms before I end. And norms are crucial here because I mentioned earlier that lots of computer scientists scrape, lots of computer scientists use bots. And they’ve done this for social good. And discussions are happening. Last year there was an amazing event here called Freedom to Innovate. And I was a little frustrated at the time about ACM and how their professional code of conduct forbidded you violating terms of service, essentially.

I’m ecstatic to announce that because of Amy Bruckman and her peers—Amy Bruckman from Georgia Tech, for those of you who don’t know—there now exists as of just a few weeks ago, the new ACM SIGCHI Ethics Committee. Again, the goal of the committee is not to resolve ethical issues—it’s not a court—but it’s to facilitate shared understanding emerging from the community. And they’re addressing the fact that what the community does matters and what the community cares about matters.

That said, going going back and forth it was hard to come up with a system of goals. CFAA violations are happening. Researchers do not want to articulate this but they are happening, and discussions are happening online and in blogs. And one of the things that Amy writes in her blog that I highly recommend is that maybe documenting what you do is not so smart with respect to terms of service. Because, as her friend Mako Hill noted, that could get people more trouble. It asks people document their intent to break terms of service. Under some circumstances, breaking terms of service is ethical, yet not strategic.

And so these discussions are happening offline, they’re happening in blogs. And it’s nice that the community is starting to come together to discuss this. And like I said, they’ve always faced ethical questions, and we have frameworks to address them in the face-to-face world. Given conversations with industry, with the government, with researchers, we can find frameworks to address them in the online world as well. And the approach that we’re finally going towards right now is policy change, policy creation. We’ve tried talking to individual companies. We’ve tried asking for data. And we really hope that this next step forward helps formalize not just us but everybody knowing what they can do online.

Matias: Thank you very much for that Karrie and Alexandra. We’ll take a little bit of time to chat with each other. And I’ll just note that in many cases Alexandra will be speaking to us via Russian, and we have a lovely translator who will be then translating her words into English. So that will set the pace of our conversation.

I’m really fascinated by the different ways in which the two of you have been disobedient in respect to the law. Like Karrie on one hand, you have these legal risks around the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act. You both have this situation where there are common practices. Researchers are scraping, people are constantly violating these terms but maybe doing it under the radar. And in your case, Karrie, you’re disobeying by participating in this lawsuit to try to change the rules. You’re participating in professional societies like the Association for [Computing] Machinery to make this widespread practice perhaps have fewer legal risks. While, on Alexandra’s side, there is a very different kind of response. The answer is to kind of build on this breadth other platforms, other efforts that people are doing to also share research and build a system that does it even more effectively and in a more widespread way.

I’m curious to hear both of you—maybe Karrie first and then Alexandra—talk about how you see the kind of established institutions and your relationship to the rules, to the kind of powers that be. In your case the companies, the law, the research organizations. And Alexandra, in your case, how you see the work of Sci-Hub in relation to the academic publishing industry.

Karahalios: So with respect to the university, companies, colleagues, you complain a lot and you end up on committees to do something about it. So for example institutional review boards have lots of complaints about should they have any jurisdiction over any legal issues, or just ethical issues. And many would argue that the ethical is orthogonal to the legal, and IRB should stick to the ethical and not the legal. By doing that, I ended up on the IRB board. Which was surprisingly—maybe not surprising—it was very rewarding. I hope I had some impact. It was nice to see studies specifically in computer science that could get approved in a day versus six to nine months, the way it was before.

Matias: Karrie, can you help us, for those of us who are less familiar with IRB, can you tell us what that is and what role that plays in the story?

Karahalios: Sorry. Institutional review boards exist at many universities. Originally they were put in place so that anyone who received federal funding had ethical approval for any research they did with government money. In most research institutions IRB approval needs to be obtained for any research study that happens regardless of whether it’s funded by the US government or not. So if somebody wants to do a study, before they can do any studies with a human subject, they have to file an application. This goes to the board. It gets reviewed. Some boards meet every month, some have expedited reviews that might happen on a weekly basis. But you need to get IRB approval before you do any study. If you’re caught not having IRB approval, the entire institution could be shut down and all research stopped until the situation is remedied. And so it was nice to see an opening discussion at the university level with IRB and how they were helping us move research forward.

With respect to working with individual organizations, we’ve had mixed results there. We wanted to work with one specific company, and we tried to be nice. We asked them, “We don’t have a lot of data that we need. Instead of wasting your time and our time collecting this data, can you just give it to us and we’ll promise not to touch your servers ever again?” They said no. That led to people not wanting to ask again, because once you get that no it makes it even worse to actually go and collect it after officially having that no answer.

Moving on to bigger corporations, I’ve had great discussions with a data scientist at Facebook. They’re among one of the best groups that I’ve ever interacted with, and they’ve been very supportive of our work. However, the plan to get the data to us did not come to pass. And that’s not anything to do with the data scientists, it had to do with the organization as a whole and legal issues in a big corporation that I honestly don’t understand.

So I guess what I’m trying to say is we try to do our due diligence, and we feel like we’ve knocked on many different doors. And we needed a new one to try to stop having to knock on all of these doors.

Matias: Which is where the legal case comes in. So I’m curious, Alexandra. Often when people discuss your work with Sci-Hub, their first reactions are to rehash the open access debates and think immediately about their own institutions, their own context, their own countries and cultures. But it strikes me that Sci-Hub is very much an outsider project for people who find them outside of those structures. Do you have a vision for changing the publishing industry? Or do you see yourself as just surveying the people who are accessing and sharing articles through your resource?

[Alexandra responds here in Russian. Subsequent references are via the interpreter.]

Matias: Alexandra, if you could allow us some pauses in the middle of your responses, so our translator has a chance to catch up with you, that would be great. But if you’re able to give a try on that.

Elbakyan: So, I think that in terms of Sci-Hub if it continues to exist, I think that the scientific publishing industry will have to adjust because they will not be able to gain the huge profits they are gaining right now from subscriptions. If you ask my personal opinion about open access, I’m for it. I’m trying to promote it.

Matias: Thank you.

Interpreter: That’s all I got.

Matias: I’m curious about this dynamic that’s in play in both of these situations, where we have a large number of people already doing the thing. And to some sense both you Karrie, and you Alexandra, have become more visible on these issues because you’re trying to address the problem in a systemic or a large-scale way. How has that been— Maybe Alexandra to start out. Did you expect that attention? And has that changed how you do your work at Sci-Hub?

Elbakyan: Well, I have to say that from the very beginning of Sci-Hub’s existence there was a lot of attention paid to it, but you might not know it because it was largely covered by local media and maybe not so much by international media.

Matias: And Alexandra, you’ve also in the United States faced legal action from US publishers. How does that affect you as someone not living in the United States? How does that affect Sci-Hub as well?

Elbakyan: Well, for obvious reasons there are a lot of challenges like domain registration, for example. Our sci-hub.org domain was closed down through a legal action, but for some other resources it’s not even necessary to take legal action. And obviously, I’m not going to the United States or Europe. I’m trying to be cautious about that.

Matias: Well we’re very grateful that you’re able to speak to us from where you are right now. I’m curious, Karrie, part of your legal strategy involves inviting other researchers who’ve found themselves limited from doing this work or who faced those challenges and asking them actually to come forward. Are you able to tell us more about what that entails and why people might find that difficult, or why they should?

Karahalios: Yeah. Well, it’s similar to Amy Bruckman’s blog post in a way. My colleague Christian Sandvig put out a call on Facebook asking people to share their stories. When I talk to the media, they always ask me to find more people. And there’s many many people; it’s not my job to out them. However, I know many many colleagues that have done this work, have gone cease and desist letters, have stopped doing the work in in most cases. But people don’t want to come out and admit this. They’ll talk about it in small circles, but they definitely don’t want to announce it to the public for fear that there might be something to come out of it.

And I can tell you that at least in our university, six out of my eight PhD students are not US citizens. I work with many faculty members who are not US citizens. For any of your that have had students who struggle getting a visa every year or who whose visa gets revoked for unexplained reasons, it’s very very hard to admit to doing anything like this. It’s hard to ask a student to do anything like this.

Matias: Thank you. We have time for just one or two questions. So if you’re able, please come up to the microphones in the middle and on the sides, and I’ll knowledge you, and you’ll just want to allow some time for the video and the translation.

Audience 1: Thank you. So I had a question about these terms of service. Because I feel like Pokémon Go isn’t telling you not to scrape their data because they don’t you to identify racial bias in the stops, right. It’s because they’re protecting their commercial interests. And I’m curious what sort of changes you think can be made to change those commercial interests so that you don’t need to worry about—so that they might not need to be as strict about enforcing the terms of service or might have different terms of service, and try to get at the problem a few steps back.

Karahalios: I’m sorry, could you rephra— Can you—

Matias: So for example, if the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act relies on terms of service, theoretically if you could just get companies to change their terms of service, that might allow researchers to audit them and maybe hold them accountable. Is that a viable strategy?

Audience 1: Yeah, and and then also sort of changing the commercial forces that motivate the companies to set the terms of service.

Karahalios: Yeah. You know, that’s an excellent point. One of the things that we’ve noted is that lots of terms of service are cut and pasted from literally other terms of service. And so there seems to be like a template that people start out with and then just add to. So that’s an approach we have not tried. I have not talked to a company and asked them to change their terms of service. I’ve talked to lots of scientists, and I’m tolk that the lawyers do not want to touch the terms of service, the terms of service need to be there. So I might ask a lawyer about that question. They’re probably more educated to answer that than I am. My attempts to talk to data scientists always end up going to lawyers, and they stop there.

Matias: One more question.

Audience 2: So first of all, Alexandra thanks for the great work that you’ve done for the community. Now, I’ve been wondering whether you get any support from academia itself for your web site. And in particular from the top institutions like MIT. So the ones that actually do have the access. But do you feel like academia is supporting your actions? And since I anticipate that the answer is no, do you think that there is something that these institutions could and should do, and that extends to to the other panel members as well. Like do you think somehow universities could leverage their power to help in these cases and to promote the causes that we care about?

Elbakyan: I’ll try to take pauses while I’m answering this. First of all, I think that MIT has poor access to publications, or allows poor access to publications. At least that’s what the frequent user complaint was. Second, as far as support is concerned I think that there is support on the part of the users who make donations, but obviously there is no official support for obvious legal reasons.

Matias: Well, please join me in thanking Alexandra and Karrie for a fascinating conversation and panel.

Ethan Zuckerman: Thanks so much Nathan, thanks Karrie, thanks Alexandra, for joining with us.