When the film was banned, I was really, really, really surprised. And what surprised me the most about the ban was the reason the Kenya Film Classification Board gave. They gave the reason that the film was not remorseful enough. They said that if I change the ending of the film and make it more remorseful, then they would give me a rating. Because they didn’t like the idea of legitimizing, or normalizing, the LGBT community in Kenya. Which was ridiculous.

Archive (Page 1 of 3)

When did we decide that we no longer need to watch news? We no longer have to watch these disturbing images? That’s why I’m writing a book. I’m thinking about these issues.

The question also does come up, you know, is there anything really new here, with these new technologies? Disinformation is as old as information. Manipulated media is as old as media. Is there something particularly harmful about this new information environment and these new technologies, these hyperrealistic false depictions, that we need to be especially worried about?

Otherwise engaged refers to our time as a time of distraction. As a time when social media is actually beginning to focus our attention on things that are distracting. And I want to talk a little bit about first of all of our new—and it’s going to sound like an oxymoron, but it’s our new sort of distracted modes of engagement.

Extremists around the world are increasingly being thrown off of social media. And so…the big question that I’m going to try to answer is, is this effective? Is it good? Is it good for the platforms? Who does it benefit? Is it good for the platforms, is it good for the extremists, is it good for the Internet, is it good for society at large?

Lo and behold humanity is fairly consistent. We would mention mornings in the mornings. We get tired sort of towards the evenings. Talk about coffee more frequently in the morning. These are the sort of normal diurnal patterns that we see on Twitter, right. As expected. But when interesting events happen and events that are out of the ordinary happen it’s very clear that they happen.

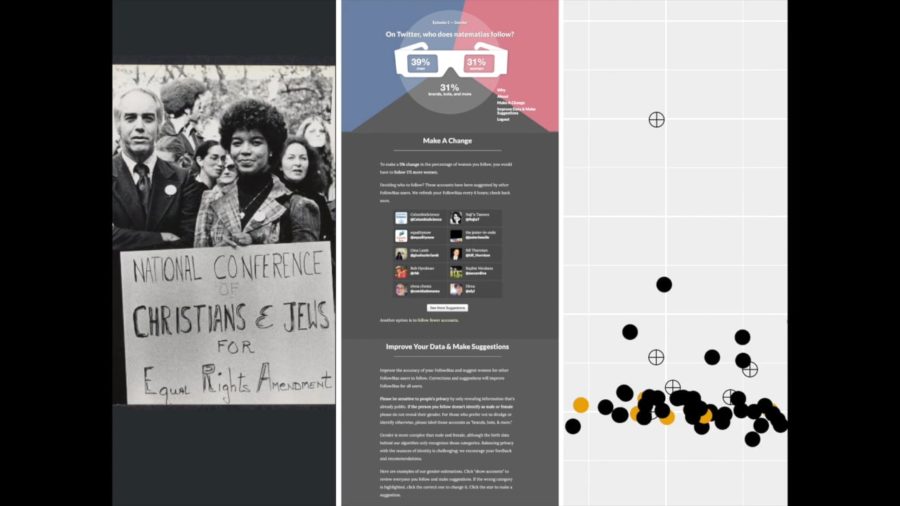

In 2011, the cultural critic Emily Nussbaum reflected on the flowering of online feminism through new publications, social media conversations, and digital organizing. But Nussbaum worried, even if you can expand the supply of who’s writing, will that actually change the influence of women’s voices in society? What if online feminism was just an echo chamber?