J. Nathan Matias: I’m Nathan Matias, a PhD candidate at the MIT Media Lab, and this is work I did in partnership with Sarah Szalavitz and Ethan Zuckerman. In 2011, the cultural critic Emily Nussbaum reflected on the flowering of online feminism through new publications, social media conversations, and digital organizing.

But then again, who is going to hear your voice if you can’t get their attention?

Emily Nussbaum, “The Rebirth of the Feminist Manifesto”, New York Magazine

But Nussbaum worried, even if you can expand the supply of who’s writing, will that actually change the influence of women’s voices in society? What if online feminism was just an echo chamber?

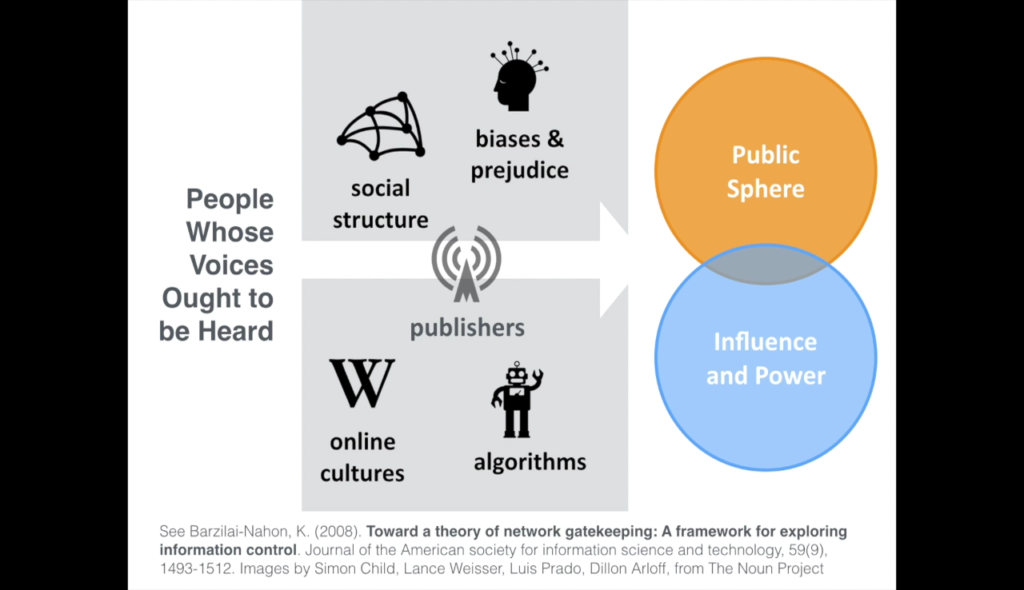

See Barzilai-Nahon, K. (2008) Toward a theory of network gatekeeping: A framework for exploring information control. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 59(9), 1493–1512. Images by Simon Child, Lance Weisser, Luis Prado, Dillon Arloff, from The Noun Project

When people’s voices reach a wide audience, their participation in the public sphere often comes with access to political influence and power. That access is often shaped by gatekeepers who influence just who gets attention. While publishers and broadcasters are classic media gatekeepers, Karine Nahon has argued that the Internet has introduced network gatekeepers that also influence online attention. Things like culture, network structures, our biases, and algorithms.

Many networked gatekeepers unknowingly direct greater attention to men than to women.

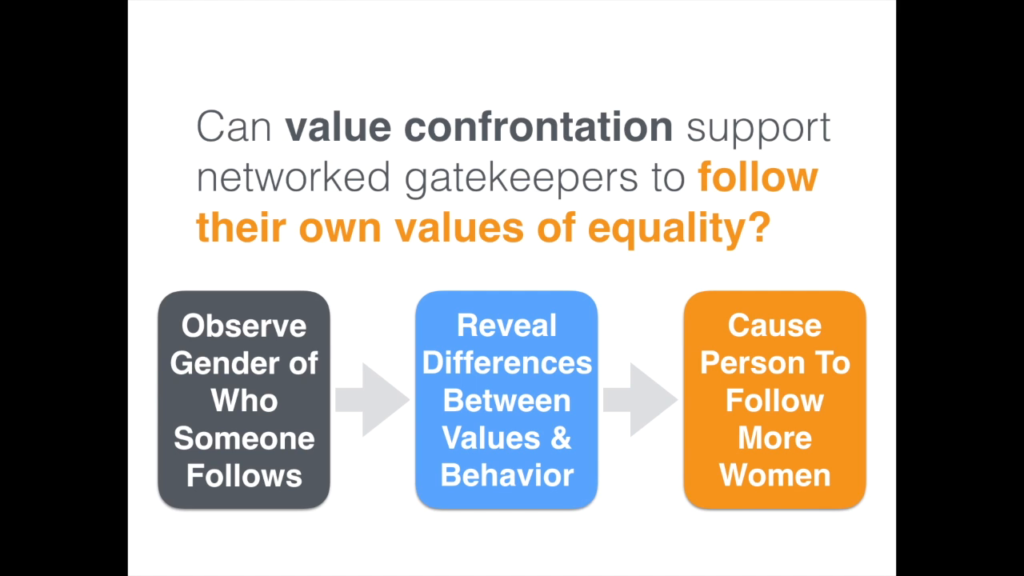

Can technologies support these gatekeepers to follow their own values of equality?

Matias, J.N., Szalavitz, S., & Zuckerman, E. FollowBias: Supporting Behavior Change Toward Gender Equality by Networked Gatekeepers on Social Media, CSCW 2017

In this study we focus on discrimination by networked gatekeepers on social media, asking if we can use novel technologies to help journalists and bloggers follow their values of gender equality.

In the first part of this talk, I’ll share some history and theories of quantitative social change toward gender equality. Next I’ll describe our novel system, FollowBias, which gives people personalized feedback on the percentage of women they follow on Twitter. Finally, I share qualitative and experimental findings from two pilot deployments of FollowBias.

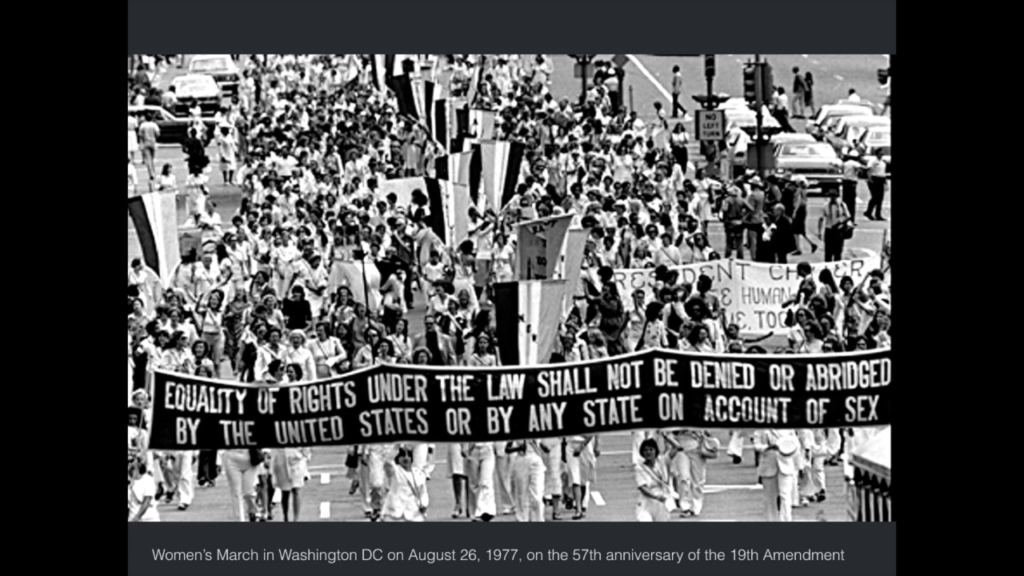

women account for over half the population… if the majority doesn’t have full political rights, the society is not democratic

Inglehart, R. Norris, P., & Welzel, C. (2002). Gender Equality and Democracy. Comparative Sociology. 1(3), 321–345.

Although need for women’s equality should be self-evident according to Norris, Inglehart, and Welzel, women in the United States still do not have equal rights under the law.

Media coverage of women is linked with political participation

more women demonstrate political knowledge and vote in places where women run and are elected for public office

Burns, N., Schlozman, K.L., Verba, S. (2001) The Private Roots of Public Action. Harvard University Press

Media attention towards women is an important link in the chain of factors that shape young people and adult women’s democratic participation, as Burns, Schlozman, and Verba found in their extensive quantitative research on this topic.

Women were no more likely to appear in online news media than print or broadcast globally in 2013, constituting 26% of people in print, broadcast, and online news

Macharia, S. Ndangam, L., Saboor, M., Franke, E., Parr, S., & Opoku, E. (2015). Who makes the news? Global Media Monitoring Report 2015. World Association for Christian Communication.

Macharia, S., O’Connor, D., & Ndangam, L. (2010). Who makes the news? Global Media Monitoring Report 2010. World Association for Christian Communication.

Yet women remain under-reported in the news compared to their contributions to society, merely a quarter of all people appearing in news stories globally.

The open nature of social media technologies could, in theory, foster greater pluralism in media discourse by providing channels for a greater number and diversity of news sources

Hermida, A., Lewis, S. C., & Zamith, R. (2014). Sourcing the arab spring: a case study of Andy Carvin’s sources on twitter during the Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 19(3). 479–499

How might social media change this? Researchers like Hermida, studying journalists on Twitter during the Arab Spring initially hoped that social media might broaden the diversity of news sources.

while it’s easier than ever to share information and perspectives from different parts of the world, we may now often encounter a narrower picture of the world

Zuckerman, E. (2013). Rewire: Digital Cosmopolitans in the Age of Connection. W. W. Norton & Company

But the opposite was always a possibility, that people using the Internet would fail to take advantage of the diversity of perspectives it has made available to us. In his book Rewire, my coauthor Ethan worried that most of us now encounter a narrower picture of the world.

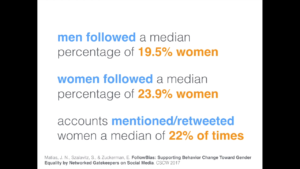

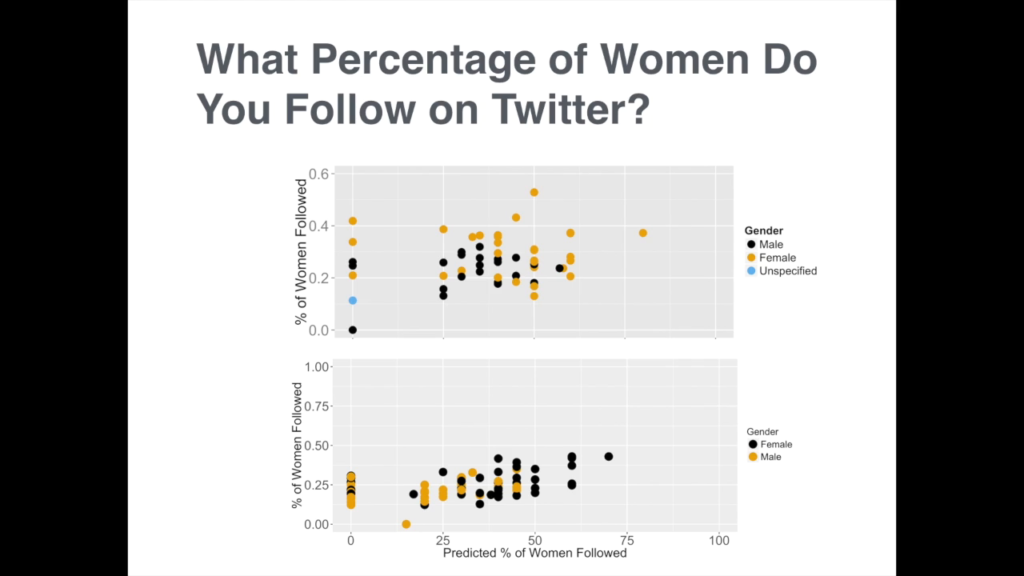

To motivate our work with FollowBias, we did a quick analysis of over 3,600 US and UK journalists on Twitter, coding their gender presentation and the name sex of the accounts they followed. We found that journalists follow and interact with an even smaller proportion of women on Twitter than the rates at which women appear in news stories around the world. While women did follow other women at higher rates, their percentages did not exceed the rate at which women appear in the news.

Women’s rights advocates first started quantitative monitoring of gender in US media during the long, unsuccessful campaign for equal rights for women under the law in the 1960s and 70s. When the equal rights constitutional amendment faced strong opposition, researchers noticed that the media narrative was being dominated by men, who often misrepresented the campaign. So they collected data and used it to advocate for reform in journalism.

In our time, data-driven advocacy continues with ongoing projects like the Global Media Monitoring Project, and VIDA: Women in Literary Arts who, monitor and advocate for women’s voices among media organizations.

I fear the attention we’ve already given them has either motivated their editors to disdain the mirrors we’ve held up to further neglect or encouraged them to actively turn those mirrors into funhouse parodies

Kind, A. Vida Count 2012: Mic Check, Redux, VIDA: Women in Literary Arts, March 4, 2013

Yet, fifty years into these endeavors, we still have no systematic evaluation of the theory that transparency around employment or content can lead to institutional change for equality.

We do, however, have evidence on personal behavior change. In the late 1960s, the social psychologist Milton Rokeach ran a series of studies at the University of Michigan prompting students to join the US National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

expose a person to information designed to make him consciously aware of states of inconsistency that exist chronically…below the level of his conscious awareness

Rokeach, M. (1971). Long-range experimental modification of values, attitudes, and behavior. 26(5). 453.

Rokeach did this by reviewing to students the mismatch between their values and behavior. He found that twice as many treatment students enrolled in ethnic studies courses, and 2.8 times more treatment students responded to a membership mailing from the NAACP, compared to the control group.

With FollowBias, we applied the idea of value confrontation to people’s Twitter behavior, building a system that could handle large volumes of requests, to observe the gender ratio of who someone follows, reveal that information to them, and hopefully cause them to follow a greater percentage of women online.

The system is related to other research designs attempting to broaden information diversity, like Sean Munson’s Balancer, and Catherine D’Ignazio’s Terra Incognita, that look at political and geographic diversity.

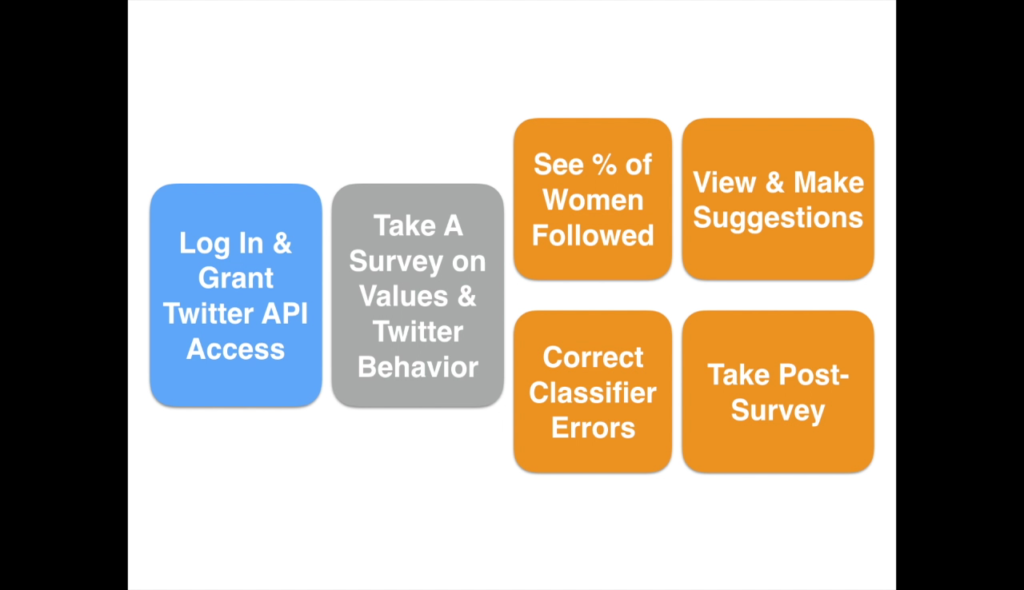

Here’s how our pilot studies worked. First, participants log in. While we collect and process their data, we ask them to take a survey on their values and imagined Twitter behavior. We then show them the percentage of women they follow, ask them to make corrections. In the second deployment, we invited them to view and make recommendations. And all of the deployments included a post survey.

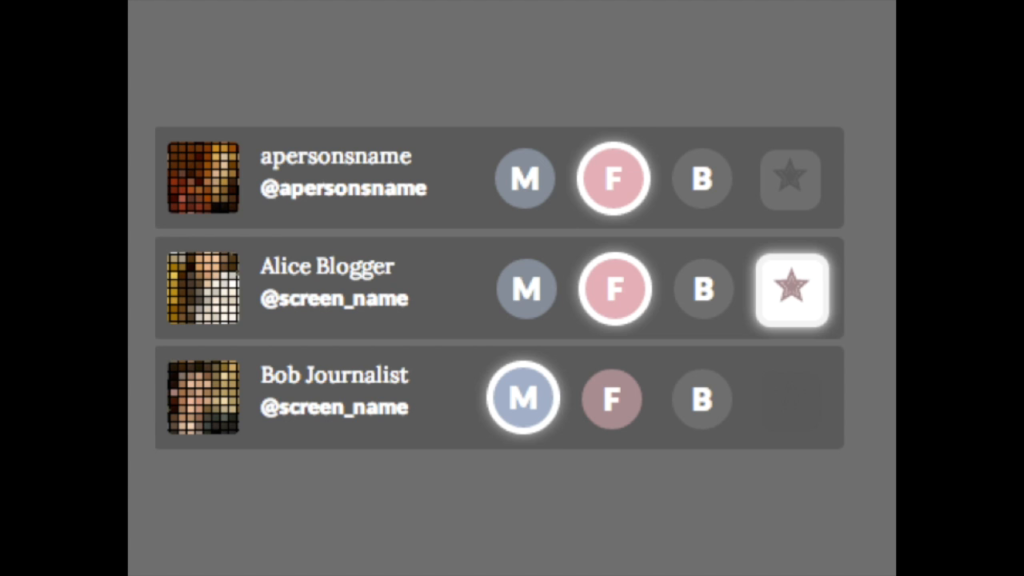

When designing FollowBias, we considered the following design choices. First, do we make the results public or private? We decided to limit the risks to the participants by keeping the results private to each individual user. We also traded off reliability in our gender ratio measure in order to provide a personalized system that could be widely used. Our corrections interface offsets that tradeoff.

In this system, we chose to limit what we collect to gender binaries, especially because we were asking people to make judgments about the perceived gender performance of other Twitter users. As you’ll see, we also explicitly designed the interface to foreground this limitation and prompt reflection on the nature of gender.

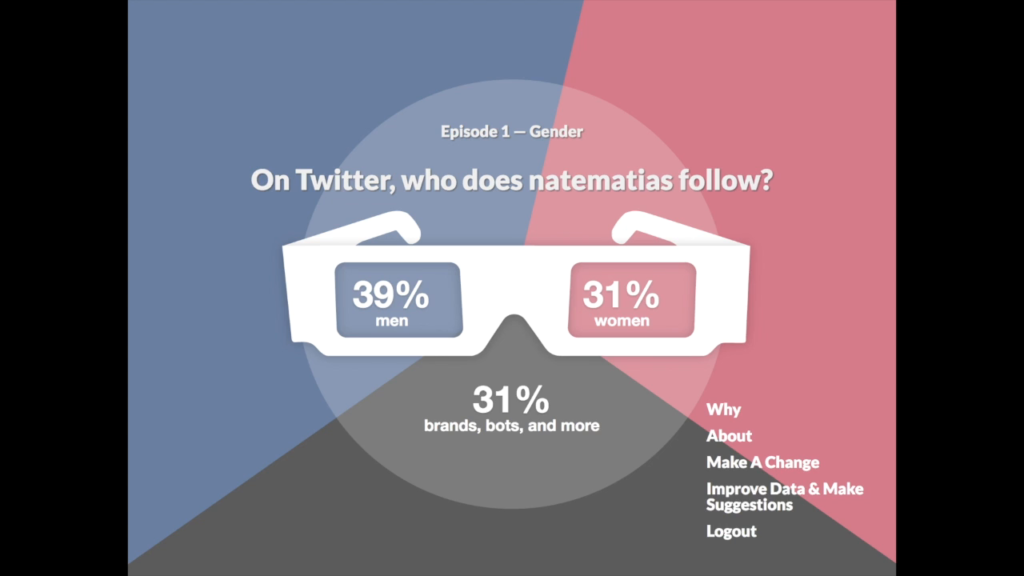

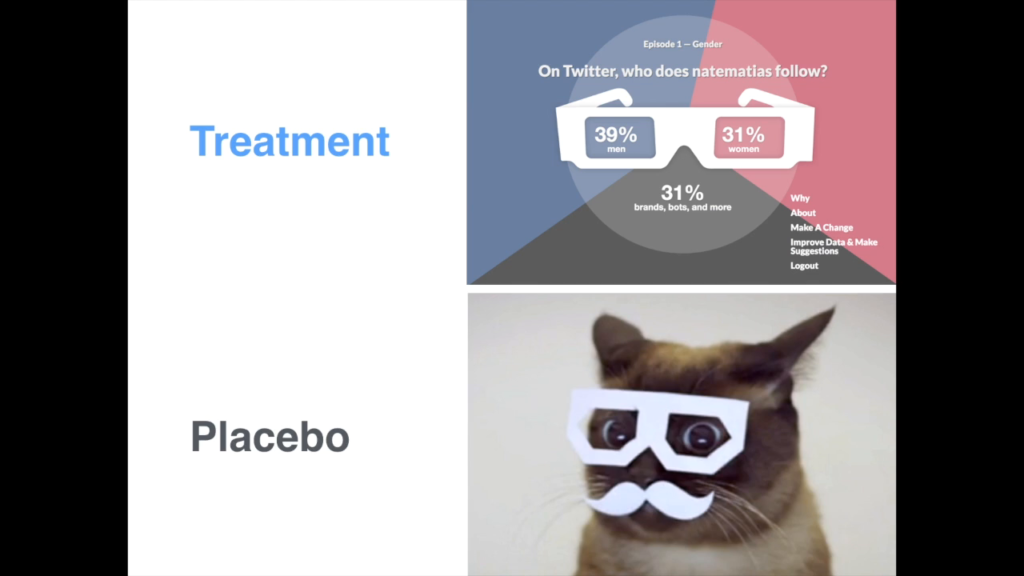

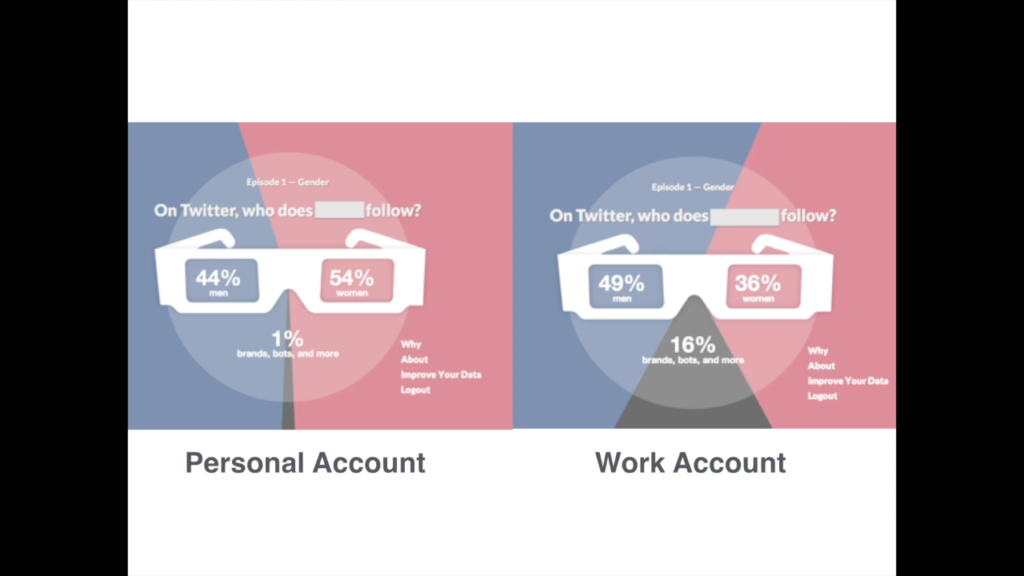

We presented a person’s results using the visual imagery of 3D glasses. This allowed us to make two overlapping points. First, we make a visual argument about the incomplete vision that results from skewed social networks. Secondly, we draw attention to overly simplistic filters on gender that are introduced by the male/female binary encoded in our system.

Next we gave users a chance to see individual judgments from our automated name sex classifier, and correct them. Participants made over 3,200 corrections in the pilot studies.

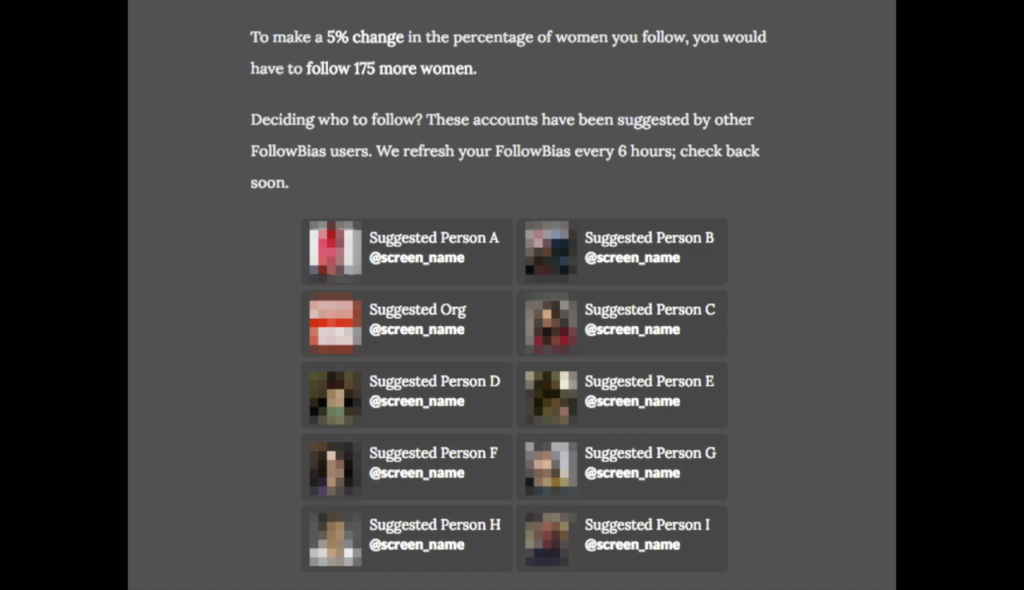

In the second pilot we also told users how many more women they would have to follow to make a 5% increase in the percentage of women they follow on Twitter. We also offered suggestions from their peers and invited them to make recommendations.

We tested FollowBias using qualitative and quantitative randomized trials in two pilot deployments in 2013 and early 2014. Eighty percent of people were given access to FollowBias, and 20% received this placebo, a photo of Dubstep Cat wearing 3D glasses.

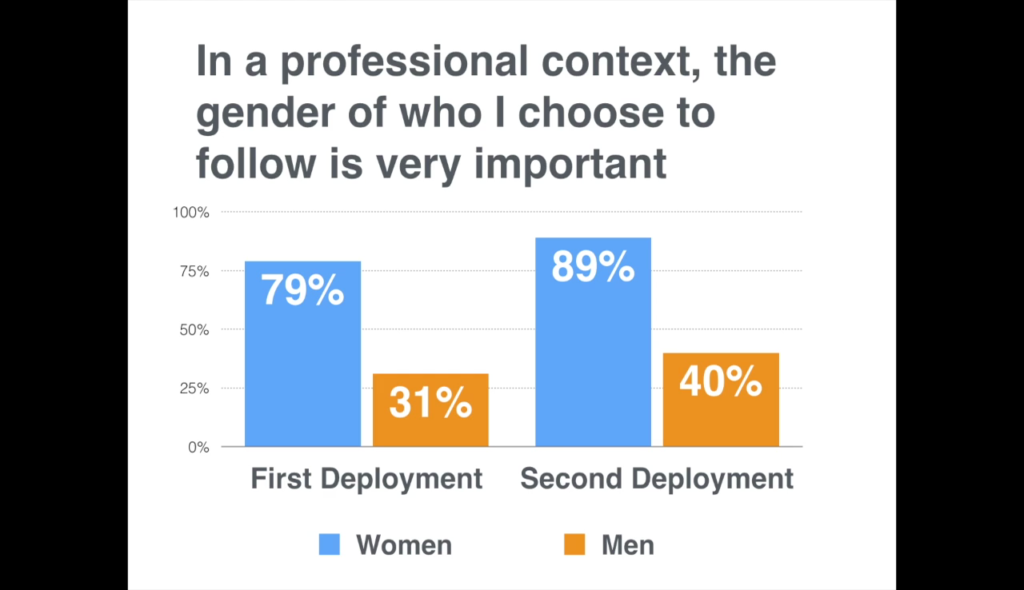

In the advance survey, women were much more likely to claim that the gender of who they follow was sometimes, often, or always important to their work.

And in these charts, the vertical axis shows observed behavior, and the horizontal shows their predicted behavior in the survey. In the first pilot, 88.2% overestimated the percentage of women they followed on Twitter. And in the second 87.1% overestimated it.

The performance of people I need to follow for politeness and algorithmic stuff is more male. […]

since the tech sector is predominantly male, this bias is visible

In our post survey we asked people to explain why their values did or did not match their observed behavior. One person pointed to external factors, describing the performance that they had to do for algorithms and their environment, saying that since the tech sector is predominantly male, the bias is visible in their results.

Forty percent of users reported distinctions between a professional and a personal account. Here’s what the difference looked like for one participant who had two accounts. Their work account followed 36% more women, and their personal account followed 54%.

Overlap between personal and professional Twitter use led some men to worry about the propriety of following women:

“I often stop and wonder if the ‘relationship’ gesture is appropriate.”

Overlap between personal and professional accounts were also cited as a reason to avoid following women, with one man writing, “I often stop and wonder if the ‘relationship’ gesture is appropriate.”

The organization I work for prides itself on being objective and I take that value seriously in my work.

it might be a bit uncomfortable if that then got published with my name attached to it

Participants also worried about privacy, fearing the public transparency could put their job risk since their employer valued objectivity.

We already receive a lot of abuse from men

Revealing the demographic of who we follow on Twitter (probably mostly women) would be likely to increase that and open us up to further criticism

One activist worried that publishing the FollowBias results could expose them to further online harassment from people who would accuse them of reverse sexism.

When confronted with the difference between their values and behavior, people will follow a greater % of women compared to a placebo group.

[presentation slide]

In addition to these qualitative findings, we also conducted two pilot studies as randomized trials, using a logistic regression to test the effect of exposure to FollowBias on a positive change in the percentage of who people follow on Twitter.

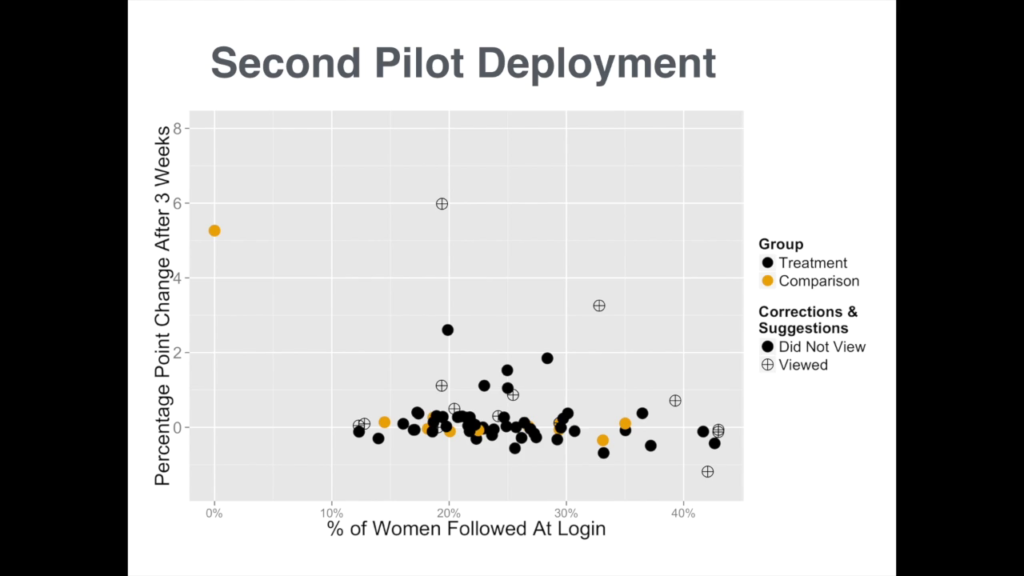

These results from the second deployment should offer a sense of the kinds of things we observed. Here the vertical axis is the percentage point change in women followed after three weeks, something that could be the result of adding two or three new women followed, or for people who follow far more counts, a change in ten, twenty, thirty new women accounts. The horizontal axis shows the percent of women followed at the time of a participant’s first login. You’ll see that the maximum percentage point change in this study is 6% points, which is actually larger than in the first pilot deployment.

1st pilot: an experiment complier who used FollowBias had a 45 percentage point greater chance of increasing the % of women they followed on average

2nd pilot: no statistically significant difference between treatment and placebo

[presentation slide]

Overall, as expected with our small sample sizes, we had inconclusive results. One pilot found an effect, and we failed to reject the null hypothesis in the second pilot.

Methodological lessons for estimating proportional changes in someone’s social network:

- percentages at wide ranging scales as dependent variables

- network spillover

But in this pilot research we did learn valuable lessons for studies that estimate proportional changes in someone’s social network. Our paper offers further details on fitting percentages when some people followed very few people and others follow a large number of accounts. We also piloted methods to account for spillover in cases where placebo participants followed treatment accounts and might also be affected downstream.

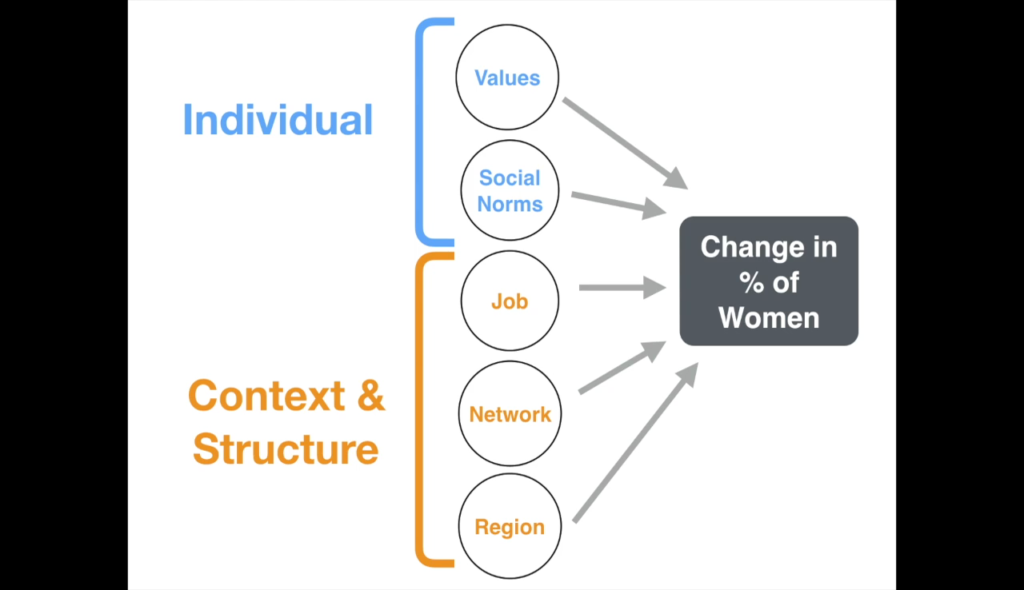

Our qualitative findings have deeply enriched the design of our next step, a larger US nationally-representative study with FollowBias. We came to this project with theories about individuals on value confrontation, and our qualitative research identified factors from a person’s social context and structure that also likely influence the magnitude of any effect from this system.

After completing these results, Sarah, Ethan, and I faced a tough question: Should we actually release this system more widely, without conclusive evidence on its effects? On one hand, we did succeed at prompting reflection and critical thinking about gender equality, and limitations of gender binaries among our users. But on the other hand, the system may not actually cause the change we care about. For now, we’ve decided not to release the system more widely.

FollowBias was a multi-year labor of love, and I’m grateful to collaborators and committee members, fellow travelers, and to the Knight Foundation and Bocoup for helping us create a beautiful, meaningful project and asking hard questions about its impact. The equality of women in society is a fundamentally important challenge. As social media restructures attention and opportunity, we need to ensure that the incomplete gains of women are not rolled back. Based on our findings with FollowBias, we argue that personalized behavior change systems offer a promising direction for further design and research towards equality online. Thanks, everyone. I look forward to hearing your questions.

Further Reference

The full “FollowBias: Supporting Behavior Change Toward Gender Equality on Social Media” paper: preprint | published