Richard Rogers: So welcome everybody. I want to introduce briefly the theme of the Winter School and this notion of “otherwise engaged.”

So, otherwise engaged refers to our time as a time of distraction. As a time when social media is actually beginning to focus our attention on things that are distracting. And I want to talk a little bit about first of all of our new—and it’s going to sound like an oxymoron, but it’s our new sort of distracted modes of engagement. So I’ll argue that there have been a number of new terms that have been coined to capture modes of engagement, so ways in which we are engaging with our machines and our platforms, which are fundamentally distracting or make us distracted. And I want to talk a little bit about so-called “solutions” to this new sort of distracted mode of engagement.

And then secondly, I’d like to talk about how whilst we’re being distracted, and engaging, in a distracted way, we’re also being measured. And these particular metrics, which I call vanity metrics, are metrics based on these distracted modes of engagement. So I’ll describe that briefly, and then I want to introduce a solution to that, what I’ve called critical analytics. So critical analytics is the subtitle of Winter School and I’ll introduce it to you—also rather conceptually but also quite practically what some critical analytics for certain new meanings of engagement could be.

So let me start off. Otherwise engaged, whilst also an expression, is quite a well-known play by Simon Gray, 1975. And it’s a play that starts off with a man, a very well-to-do sort of intellectual man, sitting in his living room. Turns on opera music; Wagner, Parsifal. And he’s going to enjoy in a sort of concentrated, focused way, a Saturday afternoon listening to opera music.

What happens to Simon Hench, as he’s called, is that he is distracted. First his tenant comes in and distracts him. Then an old schoolmate who wants something from him comes in and distracts him. And then an aspiring student comes in and asks for his attention. And what happens gradually as he’s asked for attention, he gradually falls apart. Turning into this…well not quite a madman, but turning into someone who has sort of lost his marbles, so to speak. And then ultimately at the plays end what we find is that he has completely lost his ability to care. And this is the point that I want to make. So distraction leading to a lack of care. To not being able to care.

Now, these days there are at least three—and there are others—ideas about how we now engage with new media or social media. How we engage more generally. And these are three terms that’ve been coined. One is called “flickering man” and this is by Nicholas Carr who wrote the well-known book called The Shallows. And I just want to quote really briefly what he means by this. This is Nicholas Carr writing in 2007 in a blog post that preceded the book The Shallows, and he writes:

Contemplative Man, the fellow who came to understand the world sentence by sentence, paragraph by paragraph, is a goner. He’s being succeeded by Flickering Man, the fellow who darts from link to link, conjuring the world out of continually refreshed arrays of isolate pixels[, shadows of shadows]. The linearity of reason is blurring into the nonlinearity of impression; after five centuries of wakefulness, we’re lapsing into a dream state.

Nicholas Carr, From Contemplative Man to Flickering Man

Now that’s just one term. You may have also heard the term “ambient awareness.” Now Clive Thompson, who wrote about this in The New York Times, he didn’t coin in this term. This term goes back into interaction design, computer-related design circles. But he’s referring to our seeming need to have constant up-to-the minute updates on what other people are doing. Not be able in some sense to live without them. Wanting to be “ambiently” aware of the other.

And the third one, and this is the one I think that got the most attention, by Linda Stone, “continuous partial attention” is what she coined. And she defined it as an artificial sense of constant crisis— (And maybe this is very American, actually.) An artificial sense of constant crisis so as not to miss anything. So you need to always be half on your smartphone, and half paying attention because you don’t want to miss anything. She calls this “semi-sync” mode, where she says it’s not quite synchronous, it’s not really asynchronous communication, either. It’s semi-synchronous communication.

Okay. So, what are some of the solutions to this new kind of distracted mode of engagement? I wanted to talk—this is the first part—and talk a little bit about what is increasingly being called—and there’s a new O’Reilly book out by Amber Case, 2015. What’s increasingly being called “calm technology.” So calm technology goes back to a famous piece by Mark Wiesner John Seely Brown who worked at Xerox PARC in the 1970s. Sorry, the 1990s. They were in the second generation of people there.

They wrote a piece called The Coming Age of Calm Technology. And it’s interesting because they describe a time that’s not very much unlike our time. They write, “Information technology is more often the enemy of calm.” And then here you go, 1990 this is. “Pagers, cellphones, news-services, the World-Wide-Web, email, TV, and radio bombard us frenetically.”

Of course nowadays what we have is something not necessarily all-surrounding but rather on the interface. And these are dialog boxes, popup boxes, push notifications, alarms, updates. So what Brown and Wiesner and Amber Case have called for is to encalm… (it’s actually not really a proper verb but I quite like it) …encalm the interface. And then what Brown and Wiesner referred to, we are interested in that which informs us but does not demand our focus or attention. Now this is different from partical continuous attention or ambient friend-following, etc. This is a method for quote-unquote “smoothly”—And this is Amber Case, “smoothly capturing a user’s attention only when necessary while calmly remaining in the background.”

Okay, so this encalming technology as a solution to the interface. But what I want to talk about mainly this morning to kick off is the kind of engagement metrics that have been developed over the over the past few years. And these engagement metrics, I would like to argue, measure our distracted mode—or distracted modes—of engagement. So these engagement metrics (Klout scores, etc.) are measuring “distracted” modes of engagement. And they make a number of assumptions about social media use. So what’s social media for, according to this particular idea of a Klout score or the rest?

Well, social media are for the performance of—and this is a nice place to talk about this—success theater. To showing each other that you are successful. A friend of mine, a Dutch friend of mine, a number of years ago called social media opschep—opschep media. Is that…for the Dutch people in the crowd. It’s sort of like exalting yourself, making yourself appear to be successful. And this was in The New York Times Wortham called this “success theater.”

An earlier idea of social media which is still out there—certainly with respect to LinkedIn and with respect to Twitter, less so with respect to Facebook which is increasingly more of a family or a sort of private life medium—is the idea of productive networking. So we need to be productive. So “networking,” which one would do…I don’t know, at a conference or at some sort of business meeting or whatever, has now gone online. It’s a sort of neoliberal form of networking. So we need to be productive there. And that productivity, and that success, as well as what people will want in the future—this is consumer futurism. This is a nice term that I like, it’s like studying brands online, or needs, or desires, or what marketing, what people will want in the future. So the combination of success theater, productive networking, and consumer futurism which we project into social media, these three things lead to ideas of thinking that Klout scores and other “engagement” metrics are important.

And with this I thought of Baudrillard’s—I mean I don’t normally side with Baudrillard but I…why not— Baudrillard’s idea of statistics as particular forms of wish fulfillment come to mind. And these statistics as particular forms of wish fulfillment, they have a name these days, and they’re called vanity metrics.

So vanity metrics, what do they do? They largely measures three things. Celebrity, so like follower counts, etc. Celebrity. Now Daniel Boorstin, the former American Librarian of Congress once quite famously defined celebrity as the quality of being well-known for being well-known. So it’s this sort of loop of well-knownness which…so it’s showing that you’re well-known. So this is the follower counts, etc.

The second type of vanity metric is what could call influence. Now, networks of influence, this is an old term. A lot of the classic network visualizations, network maps from beginning in the—well actually, beginning in the 30s and onward, would trace the extent to which a particular person was the spin in the web, or the hub. These are colloquial ways of phrasing the more technical idea of in-betweenness. And so if you have influence, you are highly between, highly in between—that’s a sort of social network measure. But you are highly in between strategically. So your place, your betweenness is amongst the powerful. And that’s the definition of influence. And this is also built into social media metrics.

Also the last one is—and this relates to consumer futurism—the idea of a trend, or the idea of trending as something that’s important. So the idea that there’s something that is rising, that is relatively new. So the idea of a trend is—another definition, rising relative novelty is how I would define trend or trending.

Another sort of idea, and this is people who are in the business of futurism or consumer futurism, they practice “coolhunting.” There’s a few— Actually, Faith Popcorn is one of the more famous ones in the US, but there’s also one in the Netherlands. I don’t know if someone remembers this person’s name…The TrendHunter. Anyway.

So, what I would like to argue is most of his engagement metrics, these vanity metrics, have the assumption of these particular values as being significant. Celebrity influence and that which is trending. So what I would like to do really briefly in the next sort of five minutes or so if I could do, or ten minutes if Anna will allow me, is talk about an alternative to vanity metrics. And this is what I would like to put forward almost as an agenda and only one proposed solution. This is one sort of modest proposal of how to do an alternative to vanity metrics which I like to call critical analytics.

And the first thing that one needs to do, I argue, is shift one’s understanding of social media as a site for self-presentation. Shift the idea of social media as a site from self-presentation to the site for causes. Issues. And expertise. So online, in not only Twitter—which is also oftentimes considered a professional medium—but also on Instagram and Facebook, elsewhere, causes are put forward and rallied around. And one can also derive a number of what I call critical analytics in these spaces. And I want to talk about, really really briefly, five engagement metrics. And I’ll describe them briefly to you and give you one short example and show you a couple of very very simple information graphics as well that sort of try to capture these things.

Engagement metrics are are these. Dominant voice: who dominates. Concern: who’s concerned, who’s not concerned. Commitment: are those who are concerned showing commitment? Positioning: what kind of position is one taking? And alignment: on whose side are you? So these are the five “engagement metrics” that I’d like to put forward as an alternative.

And as I said, we’re shifting the idea of social media from that it is only a social network to the fact that it could also be an issue network, a space of the exchange of substance, and also a space for not just celebrity and trend and coolhunting and trending topics, but also of authority and of expertise. And so here they are briefly defined. I’ll also circulate these slides for you. I’ll make link to them. Dominant voice and how each of them are defined. And these are actually quite simply defined here, but they’re operationalizable. I mean, you can actually use this stuff.

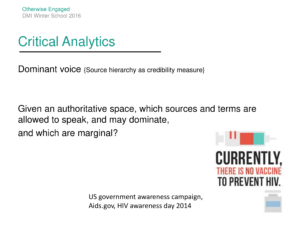

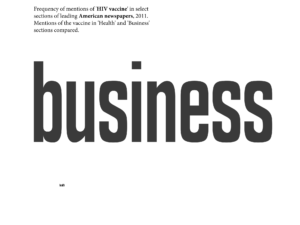

So dominant voice. Showing which source is considered most credible. Or which sources.

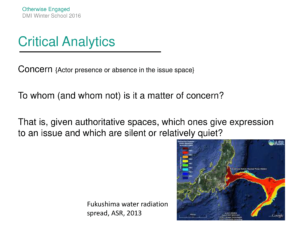

Concern. Whether or not a particular person or organization is present or absent in an issue space.

Commitment. This is the longevity or the persistence of concern. Are people only in and out of a space really quickly? Did they just follow the trends or are they committed?

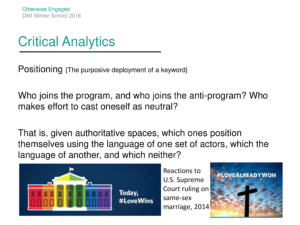

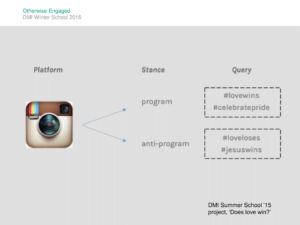

Positioning. What kind of words do you use? And I’ll come to example. How do you position the particular issue that you’re talking about?

And alignment. That is…I have here “the other company a keyword keeps,” which is a sort of funny way of saying who’s using the same language?

Okay. I want to very quickly go through each of these say that you’ve seen them.

Dominant voice. Which sources and terms are allowed to speak, and which are marginal? So this is always a question in an issue space, also in social media. I want to show you an example that has to do with the HIV vaccine. This is a brief project that we did a number of years ago where we counted the number of mentions of HIV vaccine in sections of American newspapers. So how often was HIV vaccine talked about in the business section, and then resized according to number of mentions, and how often was HIV vaccine talked about in the health section of the newspaper. So you can see rather quickly and immediately that business dominates the HIV vaccine. So the dominant voices with respe—at least in the news—are in business.

Concern. To whom or whom not is it a matter of concern? This example is from Fukushima a few years ago, when there was quite a significant nuclear accident because of a tsunami. And you see here in this graphic that is a indication of the spread of the sort of radiated water off the coast of Fukushima. And we asked ourselves the question to whom is this a matter of concern? So who is caring about this particular issue? So we queried a number of environmental organizations and we also queried a number organizations who concern themselves with species. And it turns out that only the environmental organizations and very few species organizations considered it a matter of concern. So you see here the distribution of concern over the type of organization.

The third one is commitment. That is, the longevity or the persistence of concern. So building on the previous one to whom is it a concern, but to whom is it a concern for how long? And we have today a representative of Greenpeace here who’s going to pitch a project later. We previously have done work studying Greenpeace’s longevity of concern, Greenpeace’s sort of issue commitment over time. So which issues persist for Greenpeace and which issues are more fleeting. You see here two issues, forests and nuclear. This is a tag cloud showing sixteen years of attention. So which issues did Greenpeace campaign for over the sixteen years and which ones only a few years. You see here that interestingly—I don’t know if you realize that Greenpeace actually is a fusion of two of their main issues when they started. So the environment on the one hand and peace and disarmament on the other. And over the years, the environment has risen and disarmament has—or peace, the “peace” in Greenpeace has declined.

The fourth one, and I’m almost done, positioning. So, the question here’s who joins a particular program and who joins and anti-program. The example is from the Summer School last year, where we just had the Supreme Court ruling in favor of same-sex marriage in the United States. And on Instagram and elsewhere, Twitter and elsewhere, the hashtag #LoveWins was in ascendancy and there was a counter hashtag called #JesusWins. And so what we were looking at is the difference between the one… So who chooses to join #LoveWins and who chooses to join #JesusWins. How are you positioning yourself? So we can also turn that into a critical analytic, into a metric.

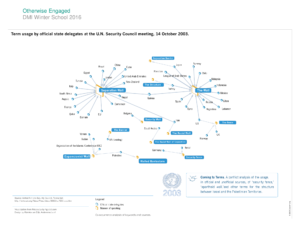

And finally, alignment. That’s what I defined previously as the company that keywords keep. That is who else is using particular words and thereby in alignment with one another. This is an example—it’s am old example, it’s a classic example—from the UN Security Council meeting in 2003. This was the first debate about the the barrier between Israel and the Palestinian territories, which the Palestinians call an apartheid wall and the Israelis call a security fence. And here’s all the different terminology used for that same barrier, and who uses it. And you see by using a particular keyword, at least in this particular graphic, you are in alignment with others who join you in using that keywords. So the choice of words is important.

Okay, so those are the critical analytics that I am proposing to you today—and there are many more, of course—which then would be an alternative to vanity metrics. So to kick off the Winter School, what I’ve done is describe our age as an age where we have distracted modes of engagement. Where we are distracted—but we are engaged at the same time. But these are distracted modes of engagement which have been described as Flickering Man, etc., ambient attention, etc., and introduced the notion of encalming technology. That’s one project that’s working on the interface. But there’s also a metrics projects. And the metrics project is to move beyond the idea that we need be distracted, that we need be always only half here. But rather that there is still the possibility and the plausibility for engagement. And that is, there is engagement if you shift your gaze in social media from the social network to the issue network and to the expert network. I’d like to thank you very much for your attention. That’s it.