Emily Rhodes: Good evening everyone. Good evening and welcome to IDFA at De Balie. Thank you for coming out. The weather is horrible, I know, and I’m really glad that we’re all here in such a full room. Very pleased to see you all here. And a warm welcome also to those watching our livestream at home.

My name’s Emily Rhodes. I’m a program editor here at De Balie cinema, where we show beautiful documentaries and organize special screenings all year round, not just during IDFA. There’s been a long-standing collaboration between De Balie and IDFA, and this year De Balie has teamed up with IDFA to bring you a series of nine doc talks over the course of nine days. And to see the rest of our program at De Balie please visit our web site.

Tonight we’ll be watching You Think the Earth is a Dead Thing, directed by Florence Lazar. And when I try to explain this film to other people I end up talking for ages because this film, what it tells us and I think it tells us it in such a beautiful way…it’s not that self-evident to the average viewer who hasn’t seen it yet. There are so many threads in this film that are woven together and it’s really hard to disentangle them.

Sadly the director, Florence Lazar, wasn’t able to make it to tonight’s screening to tell us more about this film. But I’m very pleased to announce that we do have a special guest here with us tonight who’s Dr. Francio Guadaloupe, who will kindly provide us with an introduction on the context in which he places this film as a scholar. He’s a cultural and social anthropologist, and he specializes in decolonial and Caribbean thought among other things. He works as a researcher and teacher at the University of Amsterdam. and formerly he was the president of the University of St. Martin on the island of Saint Martin, not too far from Martinique, where the film that we’ll be watching tonight was made.

And after his introduction, which will be approximately ten or fifteen minutes, there’ll be room for a couple of questions from our audience. So please feel free to ask them. I’ll come to you with a microphone, and please make sure to speak into the microphone so that the viewers at home can hear what you’re saying through the livestream as well.

After that we’ll be watching the film together, and then we can further discuss over drinks at the bar. I think Francio would be very happy to talk to you about the film in further detail. Without further ado, please help me give a warm welcome to talk Dr. Francio Guadaloupe.

Francio Guadaloupe: Good evening. Let me first thank Emily and De Balie and IDFA for inviting me to introduce this film. Secondly, I know that the main reason you’re here is to see the film, to watch the film. So I thank you for the ten minutes of attention so I can offer a supplement to the film so that you can place the film a bit better.

My talk in a nutshell:

- The earth is not the planet!

- What we call the earth—with its civilizational-continental- and racial divisions—is a descendant of Man (so too the resistance-work that speaks and works in the idiom-practice of the earth).

- The planet however, archipelagic-liquid-and posthuman, is what decoloniality understood as a critical practice-idiom seeks to institute (you can de-link from the western project, but not from the planet).

[slide]

Now, this is what I think the film is about. The Earth is not the planet. Whilst I watched the film a couple of days ago, I jotted this down and I put it, as all anthropologists—or many anthropologists nowadays do, on my Facebook page. And it’s a lot of jargon, but in a nutshell what I’m trying to say is that when you look at this film you will recognize that it’s part of a tradition that says we have to think the planet, and we have to stop thinking the Earth. Thinking the Earth is actually thinking the world in terms of distinct civilizations, in terms of continents, in terms of ownership. Who owns culture, who owns land, and how they exploit land and culture and so forth.

Planet thinking, which is different, is saying we share the globe together. We can’t fully de-link from one another. So we will have to find a way of sharing the Earth together with the rest of life that exists on the Earth. And that life is mineral life, it is material life, it is plant life, it is other kinds of animal life besides human beings.

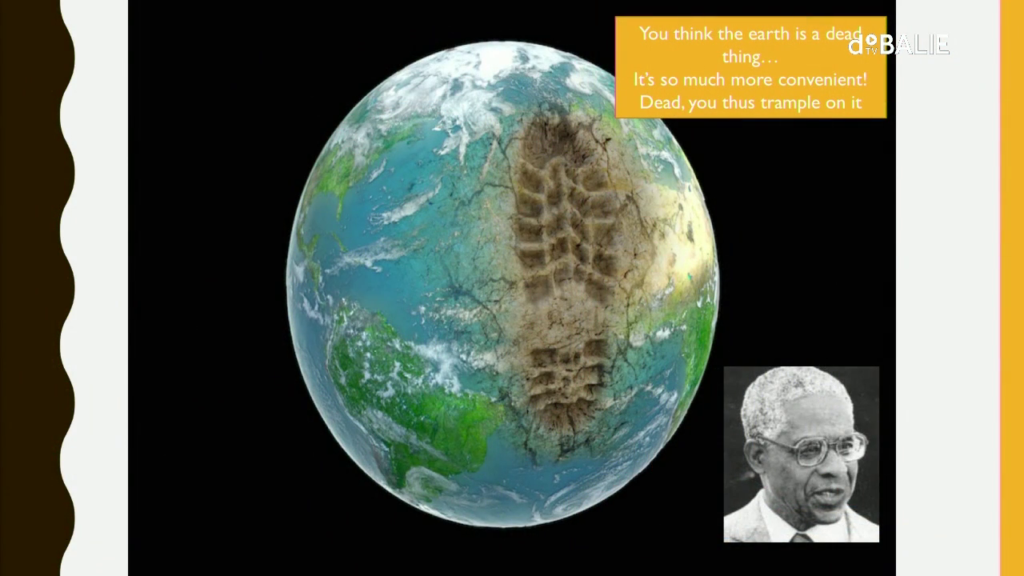

Now, I think the film is about this, and I think the film is about the Anthropocene understood in a particular way. The title of the film is taken from a drama of the Martiniquan thinker and former mayor of the island, Aimé Césaire, known for négritude, but also known for his poems in which he is actually saying you can treat the world as the Earth, and then if you treat it as a dead thing, then you can just exploit it as much as you want. It’s a convenient way of looking at life in which we actually—the life that we inhabit. And the filmmaker actually took Aimé Césaire’s theater piece of The Tempest, which is a reworking of Shakespeare, to actually do this film.

Because there two ways of looking at the Anthropocene. One way’s the dominant discourse of the Earth, and the other way is a demotic discourse of the planet. Are you still… Am I being clear? Alright. Perfect.

The dominant discourse. The dominant discourse says we arrived at the Anthropocene due to the Industrial Revolution. It says the steam engine, it says the age of steel and the age of coal, all of this led to a development of the Earth which actually was devastating to the Earth. That’s the story behind it.

It says that in the Industrial Revolution, which started in the North Atlantic (England, France, the United States, Germany), it says that whilst this was taking place there was a lot of exploitation. There was child labor, people were living in inhumane conditions. And slowly, through trade unions and through revolts, this began to change. But you can’t think the Industrial Revolution without thinking the exploitation of the majority of the population in the North Atlantic.

The argument then continues within the dominant discourse to say even though there was an emancipation of the workers and of the population, after a while the Pandora box was such that it led to more developments, and it led to a situation in which now we can actually destroy the Earth, after the atomic bomb. So it places the Anthropocene in that longer trajectory.

It also says slowly we are coming to an awareness of this—and you see that geoscientists, but also activists—and the latest symbol is Greta Thunberg—slowly we are beginning to understand that we have to change our ways. This is the dominant discourse of the Anthropocene. It’s a discourse I think many of you are familiar with.

Now, this is the discourse to me of the Earth. For what happens in this discourse is…what is the place of the Caribbean in that? What’s the place of Africa, or the place of Asia in this discourse? You will recognize the place of the…call it the non-West in this discourse is a place of actually an appendix. It’s places that are suffering and we have to do something to change it. But generally it says the story of the Anthropocene can be explained without reference necessarily to the rest of the world. You only reference them as places that are suffering because of certain malices that were done here in the North Atlantic. That’s the dominant discourse.

I’m going to say that next to this dominant discourse there is a demotic discourse, another discourse taking place. This demotic discourse that the filmmaker speaks of is the discourse that emerges in the Caribbean, one of the places. And it is the discourse that actually looks at the Anthropocene from the perspective of managerial colonies. Managerial colonies are different to settler colonies, and they’re different to mission colonies, and they’re different to the politics of indigenousness.

Settler colonies are the colonies like Australia, the USA, South Africa. These are colonies where persons from Europe came and they settled these places, and they developed it in a certain way. Managerial colonies are colonies that had few Europeans, but had people coming from other parts of the globe—in the Caribbean it was primarily people from sub-Saharan Africa and people from India and China—coming, and these colonies were managed, they were managed solely for profit. These are different kinds of ponies. Then of course you have the colonies of the missions. These are colonies that were controlled by the churches. And you have a politics of indigenousness which is the politics of indigenous people fighting for their rights.

The demotic discourse that this film presents is a discourse of the managerial colonies, and specifically of the managerial colonies in the Caribbean. These types of colonies do not play the game, or the thinking—this discourse does not play the game of separating people or separating cultures. It says you cannot understand managerial colonies without understanding the entire planet, and planetary processes.

So one of the thinkers from Martinique, after Aimé Césaire, is Patrick Chamoiseau. And he says to understand Caribbean people, you have to understand that they do not have a myth of genesis. They have myths of relation. They are related to the peoples in Africa. They’re related to the peoples in Europe. They’re related to the peoples in Asia. They’re related to the myths of the people who lived there first, the Amerindians. And all these myths have to be used to understand the globe. To understand themselves, and to understand how we actually arrived in the Anthropocene. So it is not an internal discourse to the Caribbean, it is a discourse from the Caribbean that seeks to speak of the world.

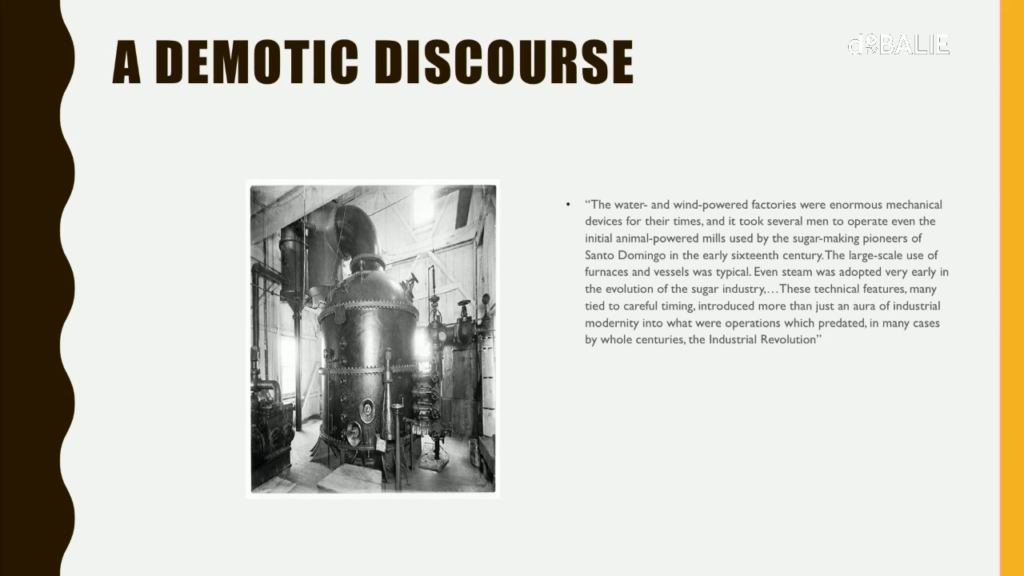

One of the things that then emerges—you take Sidney Mintz, a fellow anthropologist—is he says if you look at the European Industrial Revolution you have to ask yourself what did the workers eat? What did they consume? Where did the cotton come from? And he says the cotton came from the plantations. The sugar, which we eat all these pastries, it was produced in the Caribbean. That gave the workers the calories to be able to be further exploited, and to survive. So from this perspective you can’t understand industrialization without understanding that it was global. The factories in England, and those in Germany, were connected to the plantations and the factories in the Caribbean.

He also says even when you think about the steam engine you have to recognize that one of the first places where the steam engine was implemented was in the Caribbean. We think of the steam engine in relation to England, but we forget it was implemented there first, to actually produce these calories and these [indistinct]. So the plantations were factories, according to him.

Now, he’s building on the work of Caribbean persons that werewriting about this already in the 1940s. One of them is CLR James, who said if you take plantation slavery you have to recognize that it was an early form of globalization. The clothing that the enslaved wore was produced elsewhere. The food that they ate was produced elsewhere. They were already in an extremely globalized world that was part of their life, so they lived modernity earlier than modernity happened in other parts of the globe.

So, the idea’s not to say you have a demotic and you have a dominant, but to say you have to merge them. That’s planetary. That’s planet thinking.

So what does that mean. It means—and I’m coming to the end. It means that you have to understand the plantations in the Caribbean as uniting the field and the factory. These were two things. The field and the factory were united in the Caribbean, and those factories there were connected to factories in the North Atlantic, and the products that were coming and the people that were coming were connected to the larger globe.

It also means that you can’t understand the major players in Europe if you don’t understand that some of them were from the Caribbean. The person there in the right corner is Joséphine Bonaparte. She was born in Martinique. She’s the wife of Napoleon. This country here had a king for a while, the brother of Bonaparte. His wife was also from Martinique. So what you notice is global capital from those plantation creoles was transforming the world. And partially the creoles became part of the royalty that we know nowadays in Europe. This is a way of thinking the globe.

So, what I would like you to do as you watch this film is to recognize that the history that you are being presented is not the history of the Caribbean. It is our unacknowledged history. It is the history of the planet. And perhaps if we start to understand this more correctly we will understand that the plantation, slavery and plantation indentureship, led to deforestation. Those boats and those steam engines had to…they needed fuel. It led to a depletion of the soil. It led to the ashes coming down—the Caribbean experienced that already in the 18th century. All these things happened due to that larger colonial process. So the Anthropocene is old, and perhaps we have to think of the Anthropocene—as some geoscientists do—saying that it actually took off around the 1600s and it took off in the Empire. And it affected us all, and nowadays we have to find a common solution to a common problem. Thank you.

Rhodes: Thank you very much for that introduction. I think that was very informative. Are there any questions from our audience?

[inaudible comment from the audience]

Ah. This is something we foresaw. But we will watch the film, and there will be opportunity to ask you questions to Francio after watching it. And I think you will need to see the film to fully grasp the whole story. But we wanted to give you an opportunity to ask them if there are any right now. Ah, yes.

Audience 1: I have a very fundamental question. What does demotic mean? And what do you mean by it in your context, as well.

Guadaloupe: Demotic means…after Demos, those that are not ruling. [crosstalk] That’s what it means.

Audience 1: Ah. Okay. Okay. That makes a lot of sense.

Guadaloupe: Jargon. Sorry.

Rhodes: Any more questions? No. Okay. Then I think we’ll just have to leave it for after the film. Thank you very much Francio. We’ll speak to you afterwards. And enjoy the film, everyone.