For a really long time, I’ve been completely obsessed with ghost stories because they are these fascinating cultural items which reveal the most, kind of as Tobias said, anxieties and weird, interesting ways of thinking. Where the voices in the static are coming from, where the pipes are creaking, can often tell us about these weird things.

There’s a fantastic film called The Babadook (Which I really hope most of you have seen. You should go and see it) where the ghost manifests itself as grief, because when a woman’s partner dies, this ghost becomes a thing that she works out her own grief and her motherhood from.

They really reveal things about ourselves that we didn’t even know was possible. And I’m really intrigued by using this as a way to explore technology, and in particular data and algorithms. One of the stories I like about this is a story that Houdini told. It’s actually a real case in Victorian spiritualism, where he put up a great big grand prize of £5,000, which is about €250,000 now, to prove the existence of spirits. There was one person who came forward who was his greatest opponent, and she was called Mina “Margery” Crandon, the Boston Medium. Through a series of really elaborate bells and whistles and levers, she tried to convince him that her dead brother was speaking through her, and Houdini being Houdini (he was a genius) just said, “No, I’m not having any of that. That’s ridiculous because ghosts don’t exist. But I really like the fact that you’re trying so hard with this technology.” Because he used technology to make great big illusions about things.

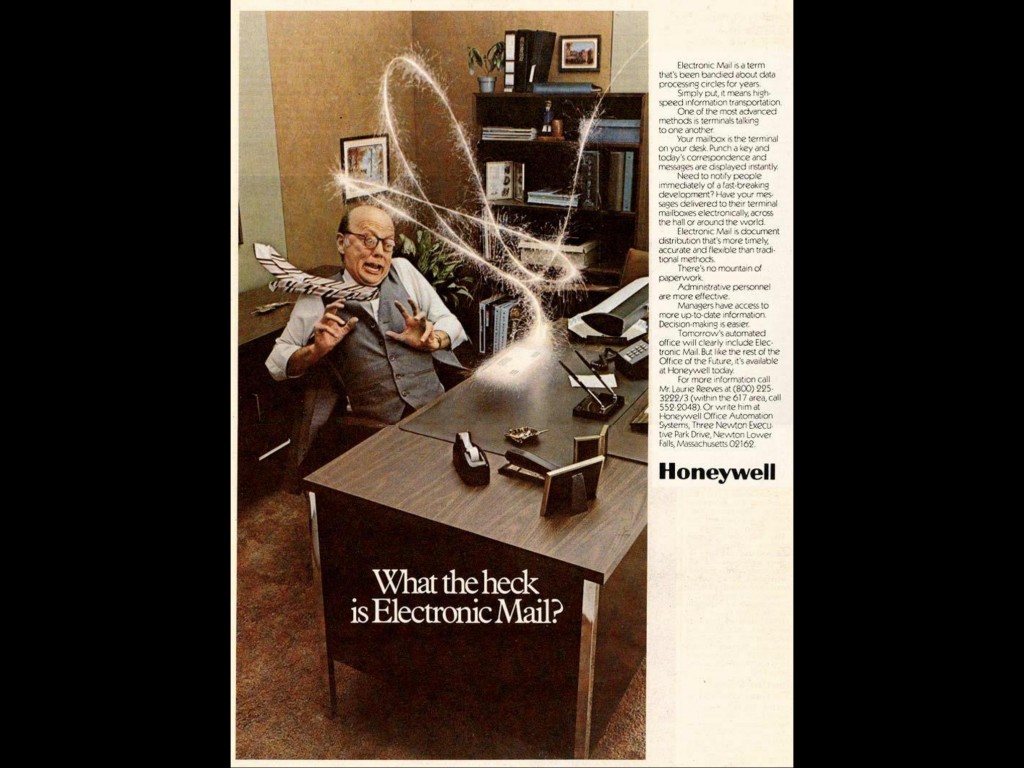

Now, fast forward a hundred years to the 1950s where the way that we suddenly marketed our technology was as science fiction or the future. And then thirty years later, it became magic, as Tobias says (We have some similarities; we do work together quite closely.) in the case of this Honeywell ad. And as I mentioned before, data and algorithms are often seen as a kind of magic in that way. So in this case with Honeywell, this data stream, a very well-recognized data stream that we know, our emails, suddenly becomes complete and utter magic. This guy is clearly really bugged out by this.

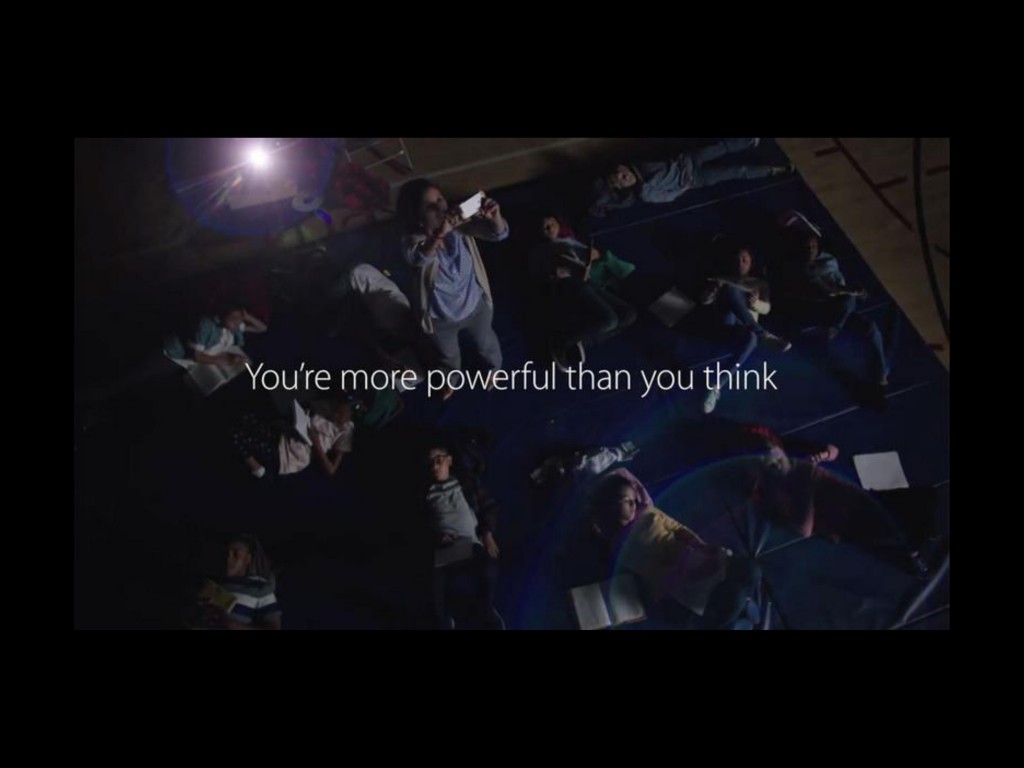

Because you don’t need to know how they work or what happens, they just do. They come to you as magic. That’s all you need to worry about. This becomes worrying when you have things like Apple’s advert which says that you are more powerful than you think. Our technology turns you into a magician. You are able to do whatever you want with this tiny computer in your hands. However, it’s actually a really powerful obfuscation technique, and it makes you think that you’re doing the magic when in fact you’re just a component in their system that you don’t have any ownership over. You can be part of their system, on their terms. They are the magicians, they cast the spell, they tell you how you can get involved.

Now, Bruno Latour, who is a science philosopher, probably one of the best-known ones, very very interesting French chap, came up with the idea of the black box, where you can see what goes in and what comes out, but not actually how the decisions are made and what happens. So, these opaque processes that we can’t see remove our agency and don’t allow us to actually have any ability to see what goes on, and this can become really problematic when we tell these stories and use these stories to explore anxieties around algorithms and data.

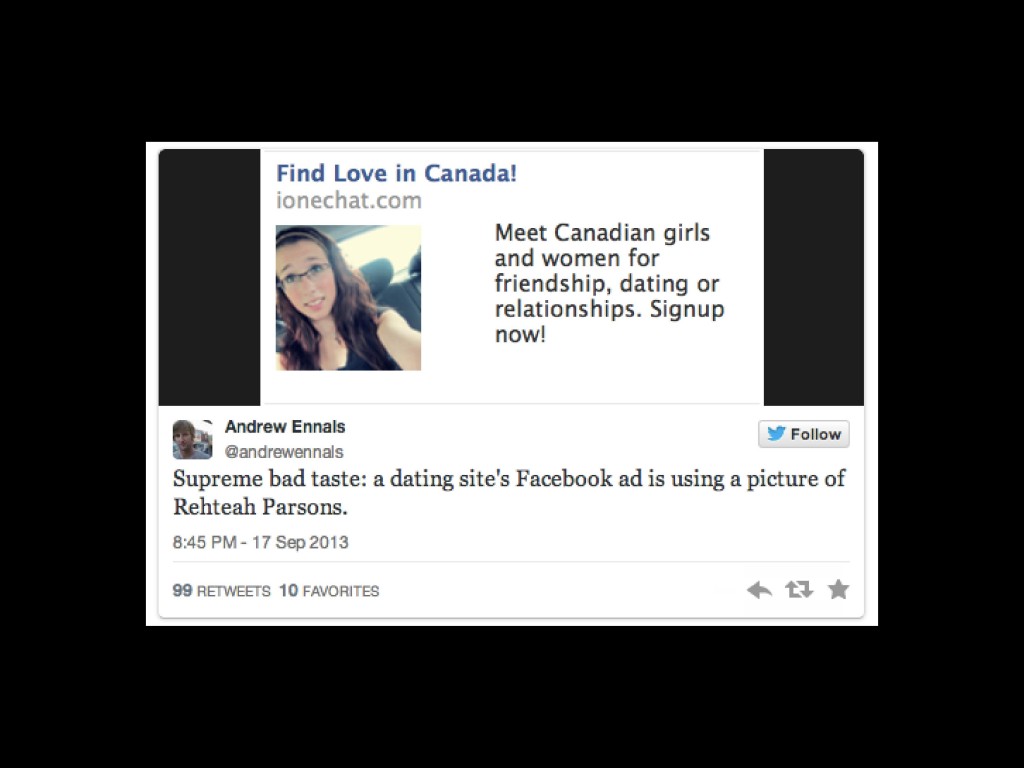

In the case of Rehtaeh Parsons, who was a young girl in 2013 who unfortunately killed herself after a quite relentless campaign of cyberbullying from some of her classmates, her picture was used massively widely on social media. It was everywhere, because it was quite a highly-publicized death. Her family and friends, as you can see, were rightly really shocked about this because you don’t think that you’re child’s going to be an advert, because the the third-party algorithms that are used by Facebook’s advertisers found this image and turned it into an advert for singles in her area. Because it just read it, through the metadata, as a woman 18–24, single, in this particular area in Canada.

Facebook apologized, but no one really knew who to blame. Was it the algorithm? Is it the company? Is it the programmer? Is it the person who at the very beginning of this entire process created that piece of code to fix a very localized solution, which was “how do I find, in this massive bank of images, a woman 18–24 who is single?”

There are more and more of these ghosts stories happening on Facebook, which worry me as someone who looks a lot at this, because you end up with the people who are the most subject to this, the most vulnerable, the people who perhaps want things to be kept to their own pace. So for instance you have pregnancies that are outed on Facebook because you searched Google for “pregnancy test” or “pregnancy advice” and then your partner that you share the computer with finds out without you having the chance to tell them. Or you have a child that’s outed by their parents because they share a computer looking for advice about their sexuality.

Facebook’s “On This Day” is a really good example of this, in some ways. It’s something that I call “means-well technology,” where a technological solution is put into a sociological and cultural friction or messiness, essentially. All of our cultural stuff is there. And in this case, a very well-meaning service tries to make your experience in the grand vacuum of Facebook feel far more personal but ends up alienating you because it doesn’t understand the context of the things that are thrown up.

This is an example of where an algorithmic solution for the burden of information (because there’s absolutely loads of crap on Facebook; we all know that) causes social and cultural friction. You end up not just being haunted by weird things that you once posted on your friend’s page, but this tweet:

So far, my Facebook “friends” video has shown me a cousin I haven’t spoken to in years, Pierce Brosnan on a horse, and my dead grandfather.

— Leonora Epstein (@leonoraepstein) February 4, 2016

Facebook thought that Pierce Brosnan on a horse was a meaningful memory that that person wants to be reminded of. But also you get the kind of slightly awful, uncomfortable weirdness, which is ex-lovers and dead friends, and friendships that you kind of would rather forget about suddenly come up because algorithms do not know the context of a photograph. Machine learning can tell you what it is, who it is, who it is in relation to other people, but not what it means to you. You have to contextualize these things. They don’t have our faulty methodology and contextualization, and in this way these algorithms aren’t actually very neutral. They’re very biased and prejudiced towards people who offer them and create them.

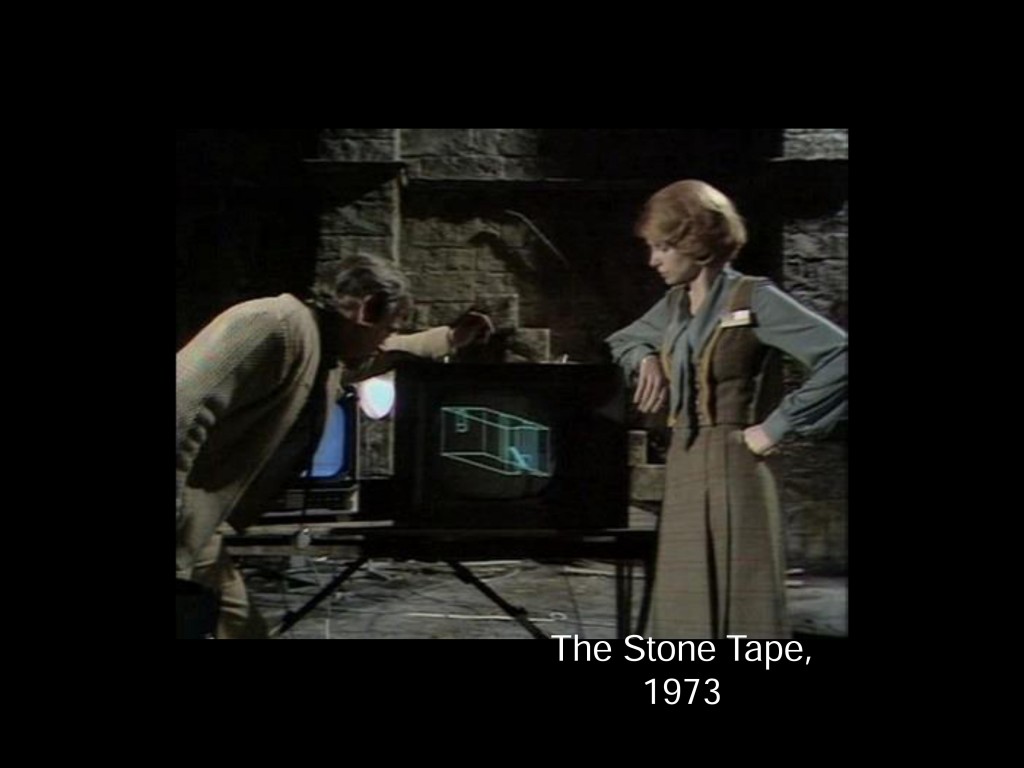

The Stone Tape theory is something that I’ve been looking at as a way of kind of coping and dealing with potential data ghosts. The Stone Tape theory is the idea that an object or house can be a recorder of memories or a recorder of things. And in the horror genre, as in the case with this piece of film from the 1970s, which is in Britain, this recorded suddenly plays back a moment of extreme emotional trigger. So you have the grief, or the birth of someone, or a massive breakup, suddenly causes these ghosts to reappear and to run havoc through the house.

Because databases are becoming like stone tapes. When the right emotional trigger hits, the poltergeist begins to take action. You don’t notice any of these algorithmic breaks in Facebook until they do actually break, and from then on you’re kind of screwed. Because you can see them but you can’t do anything about them, because you don’t know how to. Because the system is so opaque that you wouldn’t even know where to start.

Which is why it’s really hard to find them or design for them, because no designer here or programmer here can ever fully anticipate where they’re technology’s going to end up. And I’m obviously not expecting you guys to completely run through every possible option. But we should have more awareness that they exist beyond software fixes.

There’s another great ghost story (I use a lot of ghost stories. For me they’re quite a comfortable and uncomfortable way of talking about this stuff.) of the doppelgänger. The doppelgänger in classical mythology is an exact copy of you [that] you see moments before your death. And Edgar Allan Poe, as Tobias told me when we were rehearsing this earlier, did the most famous story of this and you should definitely go and check it out. And in this case, if we look at the future, when we start to see ourselves and see the breakages and things, maybe we don’t want an assistant that we can’t control. That kind of signals potential demise that we do have.

When I gave a talk very similar to this of the early days of my thinking about this in New York [video; text], I asked who is the exorcist in this situation? Who do we call on to get rid of the ghost? And I actually realized that there isn’t one, and if there is there’s kind of no point in them being there. Because once you remove a technology which causes these problems, or if you sunset a service, the problems it caused don’t suddenly evaporate. You’re still left with all the damage, so how do we go about reducing the extent of the damage, when you’re not paying attention to the fact that your technology is entering into a system not a vacuum? Your solution is not the only solution. It is entering into a world of other people’s solutions. It’s going to bump up against what other people think is the right thing, and you have to be aware of the fact that you are not the person who’s going to be the answer of them.

Other people’s technologies happen to us. Whenever we enter into a system, we deal with everything else that people throw at us. This is a quote from a friend of mine, Deb Chachra, who reappropriated the quote that Nicolas mentioned earlier, which is “Any sufficiently advanced neglect is indistinguishable from malice.” Most companies, I hope, and technologists, and designers, many of you obviously in this room, don’t deliberately want to be malicious in the technology that they’re making. However, if you don’t think about the fact that your solution is not the only one, and is going to enter into a whole host of different things, then you are going to end up causing problems and it might as well be malice. Because new mythologies are being written and summoned into reality through the dense and often really unforgiving tide of innovation. And if any of you have seen Microsoft’s product vision videos, or any [of] millions of Kickstarter videos that exist, and advertising, these are the things that are telling us the future that we should have, that we deserve, that we could have, if we let the flood of innovation happen uninterrupted and uncontested and unscrutinized.

This is a still from one of Microsoft’s product vision videos. There’s a quote form Kurt Vonnegut who says, “Everything was beautiful, and nothing hurt,” or in this case nothing breaks. And these fictions and narratives are being willed into being with these really idealized users who are very easy to solve when a problem comes up, they’re from your own biases and your own experiences, which are relatively narrow, and they’re quite dumb, really. They’re imagined by these people who want to do well. And we all do want to do well. I don’t think anyone in this room is…hopefully not an evil genius. If you are, where’s your white cat? And these narratives become really when we don’t really pay attention to where they could potentially go wrong.

A lot of my work at FutureEverything and Changeist is kind of preparing for these very uncertain futures and looking at the future through the lens of art, and design, and primarily narrative. As my colleague Scott Smith mentioned when I talked to him about this before the talk, futures is the bones. It’s the thing that kind of is the skeleton of stuff. And narrative becomes the flesh. The narrative is the thing that walks about with your technology, and walks around in your technology and has to deal with it.

Because these imagined near-future fictions progress, we really need to have these counter-narratives that push these ideals that perhaps might actually cause people some problems off course. We need to start breaking them, because if we don’t break them, who will? It’ll be the people who are subject to them. And threads need to come undone. As Near Future Laboratory’s Nick Foster talks about, we need to think about the future mundane and the broken futures and the people that perhaps we don’t often design for. Because when we imagine the future of a product or a service, we can totally anticipate in many ways a software bug or a hardware issue, but not where a technology that you’ve let out into the world might cause someone distress, or exclude them, or make their life harder.

The greatest example of this that I like using is that Apple’s HealtKit in the first iteration didn’t think that women tracking their periods was an important enough metric to include in their first iteration. They put it in the second one. Great! Thanks guys. But already women felt incredibly excluded from a system that was supposed to make them feel better. That’s a narrative that’s not okay. An app update is not enough. As I mentioned in the exorcist example, the damage has already been done by that point.

So to start to create these stories which are a bit one-key and broken and weird can help us to become more resilient and problem-solving and far more empathetic, and think a lot more about the futures that perhaps other people could be living with our technology. I wanted to give a few examples of technology being subject to these biases that we might not necessarily think of.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TqAu-DDlINs

This is a Scottish TV show called Burnistoun. These two guys are trying to use a voice recognition elevator, and they’re saying in very Scottish accents, “Eleven. Eleven. Eleven.” And this lift is just basically saying, “I’m sorry, I do not recognize that command,” because it was designed by Americans. And they didn’t ever think that someone with a heavy Scottish Glaswegian accent (I’m sorry to all Scottish people that I tried to replicate that.), that it doesn’t work for them. So you’re very much subject to these biases, and these biases lock people out of your technology because you didn’t think they would use it in that way.

Still from “Curious Rituals” by Near Future Laboratory

This is a great scene from Nicolas’ film, actually, from Near Future Laboratory where he works, from “Curious Rituals,” which I do recommend that you go and watch, where the user of a smart car shouts into a car phonetically rather than the way that this name is said, to recognize a name that’s not American and not English. So she has to kind of say Jer-al-do rather than Geraldo [Spanish pronunciation], which is the guy’s name.

And now back to a more contemporary ghost story. I really hope some of you have had the chance at least to probe into the weird world of Charlie Brooker’s Black Mirror. It’s kind of like a very modern Twilight Zone, in some ways. In this particular ghost story, this woman loses her husband, unfortunately, and her very very well-meaning friend says to her that there’s this fantastic service that you can use which will literally bring him back to life using all of his data, his social media profiles, his voice calls, everything possible. Which, for a start, indicates a future where private companies have access to every single bit of your data to do this, which is terrifying enough.

But in this case, this service that tries to do well and tries to give you comfort in a time of incredible grief actually scares the hell out of this woman. She’s sitting on the end of a sofa here, but there’s a fantastic scene where she’s locked in the bathroom because she’s absolutely terrified of this thing that’s not her husband, not this person. It’s a manifestation of him. He is the doppelgänger. And he symbolizes this anxiety that we have around our data, where we start to see things and they creep out of the cracks and things.

Using narrative futures as I am, which is a lot of what look at, is looking beyond trend reports, using them as an informant, and horizon scanning, which what a lot of futurists use. And bringing in ethnographers and anthropologists and artists and critical designers to come into these processes to kind of pull them apart and break them. Because we need to create more stories about potential hauntings, where our data could create harm. Because although it might not at every single instance, knowing that it could allows you to slow down and think twice.

In the early days of your technology, way back before prototyping the product, process out the kind of futures it could have, not what you think it’s going to have. Because even if you think it might do something weird, hand it to someone else, give it to a different diverse group and say, “Okay, so we kind of broke it in this way, but we know that we’re not everyone. So maybe you guys have a go at it.” Because when you think about where someone’s quality of life is compromised because you didn’t think it would ever be used in that way… There’s a really interesting example that I always use about the idea that if you’re in a support group and a child says to you, “I think I might be gay. I want to look up information about this,” and then a few forum posts later he says, “My parents have kicked me out because they found out from their Facebook advertising that I’m gay. They’re not happy about it.” We can’t anticipate for that, but knowing these kind of narratives do take place is really important. Because we want to have a future where we don’t just try and design for the best possible circumstance, because realistically the world’s messy enough as it is. It’s not going to suddenly clean up over the next few app updates. That’s ridiculous.

So tell more ghost stories. Freak yourselves out a bit. Be a bit weird. Here’s Patrick Swayze. Thank you.

Nicolas Nova: Thanks, Natalie. One of the questions we got was about the haunted algorithm thing. Can you elaborate on that?

Natalie Kane: The haunted algorithm?

Nova: Yeah, haunted algorithm. Can there be a haunted algorithm…

Kane: I think it’s [?] because algorithms are a very logical system. They know what’s true and false, but the problem is they kind of have a puppet master behind them that chooses the datasets that they choose to take from. They choose to determine what’s true and what’s false. And then you think, hang on, this true and false might not be the same as someone else, and they kind of create these weird gaps where they’re used by different people in different conflicting systems, and that’s where the ghosts and weird hauntings happen.

Nova: Can there be good haunted machines or algorithms? Because it’s part of the friction of everyday life to have friction, to have things that break. That could be funny, that could be original. Not all frictions are bad.

Kane: Yeah. A lot of frictions are quite amusing. There’s definitely a place for magic as a colleague of ours, Ingrid Burrington, says, there’s a place where you can use it to explore weirdness and explore strange things and be delighted by stuff. But there’s a problem between—and Tobias mentioned this—empowerment and enchantment. Enchantment kind of pulls the wool over your eye, but empowerment gives you the ability to do the magic. There’s a course that Greg Borenstein runs at MIT that talks about design as using magic. I’d like to explore a little bit more what they mean by that, because I like the idea that we still have a capacity and a place for magic in the world and to be excited and delighted by stuff. But it’s just making sure who casts the magic and who gets to make that magic is thought of.

Nova: Thank you very much.

Further Reference

Bio page for Natalie and session description at the Lift Conference web site.

Natalie’s page about this presentation, including the accidental inspiration for its title.