Alan Cooper: So, bonjour messieurs et mesdames, haut et bas. That’s all the French I know. Thank you very much for tolerating the monoglot American. And thank you to Roberta and Gilles and Fredrik for putting on this event and for inviting me here. It’s my pleasure to be here, and it’s a pleasure to see all of your smiling faces.

It is very much a a pleasure for me to be here, and it is a privilege for me to be allowed to address you all in the place of honor, the first speech of the first day of this conference. And it was ten years ago that I was accorded a similar honor when in 2008 in Savannah, Georgia I was the first speaker on the first day at the very first IxDA conference. It seems fitting to be here.

I’ve always supported the IxDA from its beginning, and I’m proud that former colleagues of mine were involved in the creation of the organization. Because the IxDA is the Interaction Design Association, and interaction design is a discipline composed of many… It has many roots, it’s a tree with many roots. And some of those roots are…branching off in ways that…there’s a kind of a thread of aesthetics and personal vision in the industry? And while those are…interesting, they lead away from the user. And to me, interaction design is about designing the behavior of technology in service of the user, and that is the core of who we are and what we do. In other, words IxDA represents user-centered design rather than designer-centered design.

So, some of you may know my wife. Sue and I, in just this past October sold Cooper to Designit, a European design firm. And we have the opportunity now to think about other things, and pursue other avenues. And today in my talk you’ll see what I’ve been working on. Is everyone good? Enough coffee? You’re good? Have I had enough coffee?

Seven years ago, Sue and I sold our house in Silicon Valley and we moved to this fifty-acre ranch in the country, which we named Monkey Ranch, after our cat Monkey. It’s in West Petaluma. It’s about an hour north of San Francisco. And to my surprise, I found an entirely new perspective on the high-tech industry amongst the sheep and the chickens and the tall California grass. And that new perspective is the basis for this talk. And it’s why pictures of Monkey Ranch are the background for many of my slides.

So let’s start out. I’d like you to do a little thought experiment with me. Imagine that you work at a giant social media company. Every day you access massive collections of user data, analyzing it so that you can give users exactly the posts that they most want to see and not the posts that they don’t. Your work is so good that you’ve created a targeted advertising platform that’s nearly perfect.

Then one day, you discover that Russian government hackers have used it to influence an American presidential campaign, using the psychological profiles that you created. The Russians identified susceptible end users and flooded their feeds with hate messages, fear-mongering, and outrageous lies about progressive candidates and organizations. It’s then that you realize that your work directly contributed to the destruction of a representative democracy.

Or, imagine that you are a staff researcher at a major computer software company. You’ve been working on really cool learning algorithms for conversational user interfaces and created a chatbot to show off what your AI is capable of. Your boss is so impressed with your work that he lets you deploy the chatbot on the web.

But hackers discover your chatbot and begin filling it with lies and prejudices, and telling it terrible things. Within one day, using the software that you wrote, all your chatbot can do is spout, racist, misogynistic, and hateful venom. Your boss disables it immediately. Then you realize that your work can easily be turned into something very destructive.

Or, imagine that you became an intellectual property lawyer because you want creative inventors to be inspired and supported. You worked for years to empower innovators to protect their ideas.

Then one day, you discover that the overwhelming majority of patent lawsuits are pursued by patent trolls, those who patent ideas but never actually make things. They just wait for someone else to create a product, and then the sue them for undeserved royalties. Only then do you realize that your life’s work has empowered a few greedy people to engage in legalized extortion.

Or, imagine that you’re an expert in linguistics and you’ve spent years working on new spellcheck algorithms. Your work involves machine learning, artificial intelligence, and very clever indexing methods. It’s deployed globally on a computer named after a fruit.

Then one day, it’s discovered that it autocorrects some prescription drug names into completely different drugs. When Duloxetine becomes Fluoxetine, there’s a high likelihood that while no one will notice, someone will suffer from taking the wrong medication. It’s then that you realize that your innovations have brought harm to innocent people.

Why is this happening? Is it inevitable that our coolest technical achievements become agents of evil? No. It is not inevitable. Today I’m going to talk about practical methods to avoid creating high-tech products that enable toxic behavior.

The technology we build has certainly made people’s lives easier and better. But unintended side-effects happen more and more often, and they tear at the fabric of society. We are good people, and we do our jobs with the best of intentions. But we find, to our dismay, that we have enabled bad behavior and bad outcomes.

Where did this evil stuff come from? Are we evil? I’m perfectly willing to stipulate you are not evil. Neither is your boss evil. Nor is Larry Page or Mark Zuckerberg or Bill Gates. And yet the results of our work, our best most altruistic work, often turns evil when it’s deployed in the larger world. We go to work every day, genuinely expecting to make the world a better place with our powerful technology. But somehow, evil is sneaking in despite our good intentions.

It’s like the way Dr. Frankenstein didn’t understand the monster he created. There is a mechanism at work here that we don’t fully understand. We need to deconstruct this phenomenon so that we can recognize it and prevent it from happening again.

In the 1940s, [J. Robert Oppenheimer] headed up the Manhattan Project, the largest scientific effort the world had ever seen. His job was to invent the atomic bomb so that the United States could use it to end World War II. But when Oppenheimer saw that first atomic explosion, he realized that he had created something terrible. This was Oppenheimer’s moment. Not only was he a god of physics and science, but now he was Mars. He was Ares. He had also become a god of war, bringing chaos, suffering, and death.

Today, we the tech practitioners, those who design, develop, and deploy a technology, are having our own Oppenheimer moments. It’s that moment when you realize that your best intentions were subverted. When your product was used in unexpected and unwanted ways. It’s that moment when you realize that even though you aren’t racist, your algorithms might be. It’s that moment when you realize that your software, designed to bring people together instead is driving them apart into tribal isolation. It’s that moment when you realize that the social and economic checks and balances that prevent excess and abuse don’t work anymore. And nothing harnesses your your creation, and your creation is beginning to run amok.

My first thoughts are, who can we blame for this? We can’t blame the technology, because it does amazing good things for us, as well as bad. It’s easy to blame the founders, your coworkers, the venture capitalists, your annoying boss. But they’re just as troubled by this as we are. Tony Fadell, the founder of Nest, wants a Hippocratic Oath for designers, where they pledge to work ethically and do no harm. And Sam Altman, the president of Y Combinator, is writing an ethics constitution. And Bill Gates is giving billions to charity. Our narrative-seeking, storytelling brains want a villain. But this isn’t a Walt Disney movie, and Cruella de Vil is not coming for our puppies. Really. There’s no one to blame.

It’s a systems problem. It’s as though the Titanic ship of technology is sinking. But we never hit an iceberg. We’re filling with water but nobody can find the leak. We keep searching for the giant rip in the hull caused by the evil iceberg, or the evil captain, or the evil shipbuilders. But we find no evil, and we find no giant hole. Yet the water keeps getting deeper.

Trying to find a single point of failure or origin of malice only works on simple systems. But all of the tech products we build are complex systems, and their network environment is yet another level of complex system. The water, the evil, isn’t coming from one big hole but from a constellation of tiny ones. Like 100 million microscopic laser-drilled holes in the hull of the Titanic, they collectively add up to a fatally huge gash. And this is just what a systems problem looks like.

Systems problems are by nature distributed ones, and their solutions are distributed too. We put those millions of tiny leaks into the system. There was no malice, no evil. That’s why we have to apply our efforts to preventing tiny leaks, rather than trying to predict and then stop a single catastrophic event. The technology we use changes so fast it renders our good intentions irrelevant and inadequate. No matter how well-intentioned, our good permutes into bad. Our innocence simply isn’t sufficient. We have to master this system.

We need to identify the weaknesses in our products and business models when they are tiny, embryonic things. We have to get ahead of this phenomenon, because once it emerges it’s too late. And we need to do it in a way that transcends the technology. So it applies to everything. So it’s long-term. So that it’s sustainable.

The blogosphere is awash in longform commentary asking how we could bring ethics back to technology. People tell us to be good, but they don’t tell us how. There’s a lot of work to do. But first we have to have a clear goal. The founders of Facebook, Google, and a thousand other companies large and small have as their primary goal to make money. Their second avowed goal is to not be evil; to do no harm.

There is abundant proof that this does not work. When your primary goal is to make money, all other goals devolve into mere words. “Don’t be evil” is too vague, too simplistic, and too hard to relate to the daily work of tech. Besides, it’s always in second place, and it always loses to the imperatives of making money. We need a new goal, a new rubric for success. One that makes us better citizens, first, without stopping us from making money, second.

Here’s my proposal: I want to be a good ancestor. My goal is to create a better world for our children, both yours and mine. And their children. Every day I ask myself does what I’m doing to make the world a better place than when I found it. When you think like a good ancestor, you’re forced to think about the whole system. You can no longer maximize isolated measurements at the expense of others. You can no longer excuse bad behavior in the interest of profit.

Conservative political dogma says that you can either make money or you can be a good citizen, but not both. This is a lie. You don’t have to behave badly to make money. Virgin, Costco, and Patagonia are all proof that you can be a very profitable, good ancestor. As Steve Jobs said, profit is a byproduct of quality. People are very loyal to good quality, and not at all loyal to products that behave badly. So while there is value in making money, I value even more making the world a better place for our children.

By making good ancestry our primary goal we can work to prevent our products from turning to the dark side, and we can still build profitable businesses. Every day instead of saying, “Do no evil,” ask, “How can I be a good ancestor?” Being a good ancestor is my goal, and I want you to make it your goal, too.

While the first step is having a clear goal, there are many subsequent steps needed to solve the challenge. It’s all giving me a strong sense of déjà vu—that’s my other French word. That sensation where you feel like you’ve been there before. Twenty-five years ago, as personal computing was exploding on the world, it had become clear the technology was hard to use. Everyone knew that we needed to make software user-friendly, but no one knew exactly how to do that. Back then plenty of smart people thought it couldn’t even be done. Someone had to define user-friendly in measurable ways. Then develop a taxonomy for the field. Invent a set of tools. Create a process framework. Establish clear examples demonstrating the benefits. Train a cadre of skilled practitioners. And then take that show on the road and proselytize it.

Well, that’s what I did for interaction design during the nineties and the aughts. Our presence here today proves how design has become an important role. It’s well-known, trusted, and omnipresent. Now it’s time to do the same thing for being a good ancestor.

Nice hair. Renato Verdugo is my brilliant young Chilean collaborator. And we are developing a framework and tools that we call “ancestry thinking.”

The first step is awareness of the problem. It’s vital that practitioners pay attention to how their products are applied in the real world by actual users.

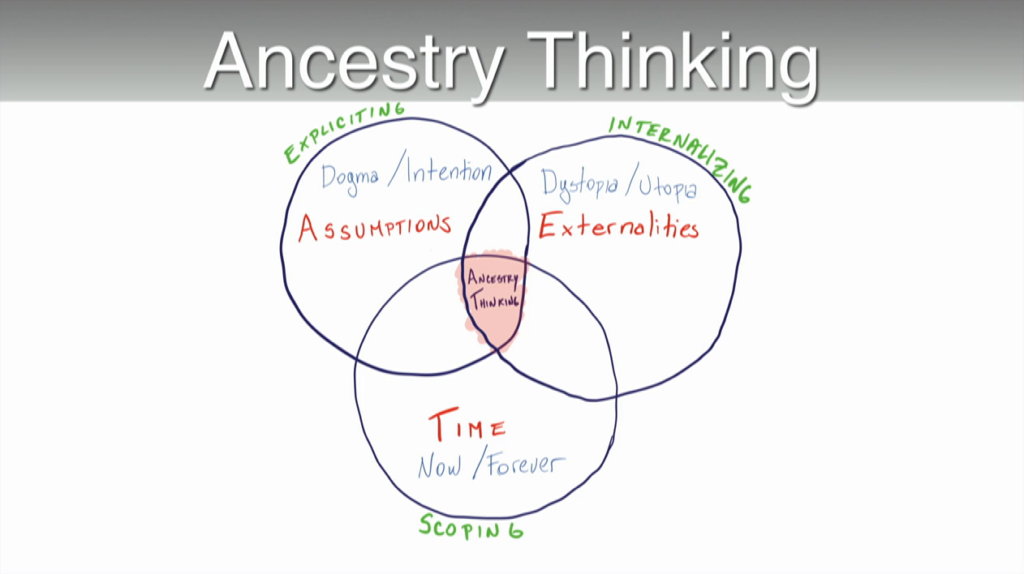

The second step is creating a language, a taxonomy that lets us see where and how those millions of tiny holes get drilled into the hull of technology. So far we have identified three main vectors by which bad behavior creeps into your product: assumptions, externalities, and timescale. We examine these vectors by asking ourselves three hard questions.

First we must ask what assumptions are we making? Whenever we design a solution to a problem, we base our thinking on certain assumptions. If we don’t rigorously examine all of those assumptions, our intentions can become lost, and we open the door to bad ancestry.

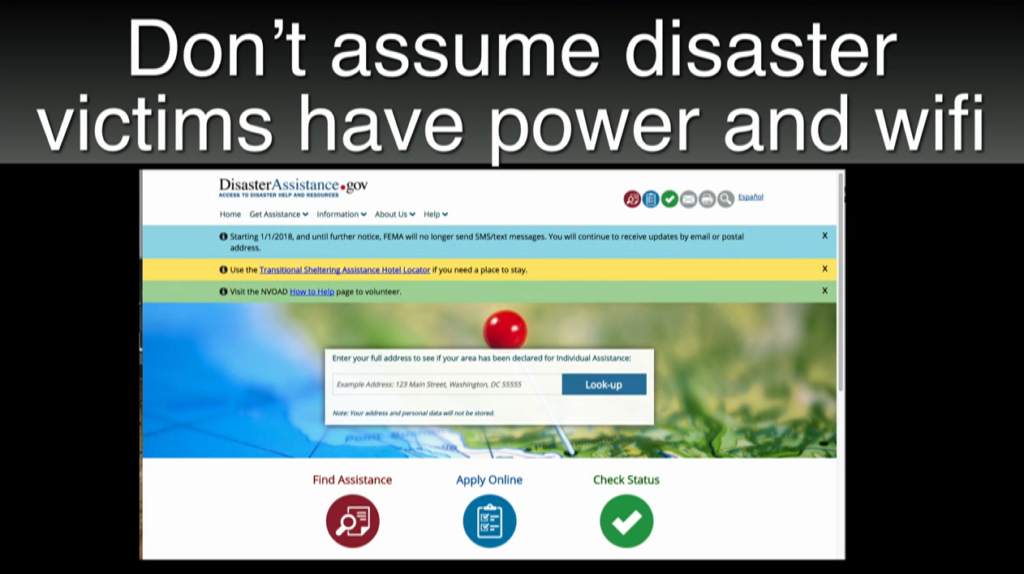

Someone was making assumptions when they created their disaster relief website, requiring users to have electrical power and WiFi, scarce things in a disaster.

Someone assumed that the white engineering staff was representative of the people who would use their new sensor-equipped bathroom soap dispenser. And it works fine, if your skin is white, but it fails to detect black skin. A good assumption can turn bad over time, or in different circumstances. So you have to identify, inventory, and regularly reexamine every assumption you make.

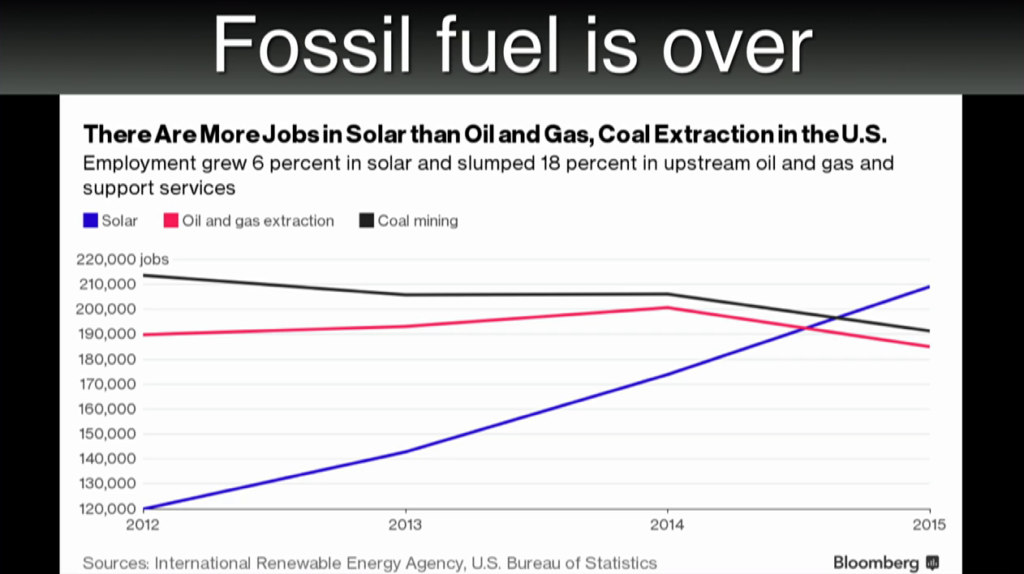

The fossil fuel industry used to provide a lot of jobs and economic opportunity in the USA. Not anymore. Solar is where the jobs are, where the growth is, where the opportunities lay, and a proving ground for tomorrow’s leaders. Unexamined assumptions become dogma, and dogma is the opposite of intentionality. To be a good ancestor, we can’t let anything hide. We must be explicit.

Secondly, we must ask, what externalities are we creating? Externalities are those things that affect us, or that we effect that are pushed out of our attention, whether by choice, neglect, or ignorance. Everything we do is part of a complex web, and nothing is completely external.

Every Monday morning, a big green truck comes to take my trash away. But there really is no “away.” It takes my trash down to the landfill by the river. My children are going to have to deal with that landfill. Whenever you say, “That’s not my problem,” you create an externality. And every externality is a hole in your boat. It’s another way bad ancestry creeps into your world.

For example there’s a rideshare company that provides a great car hire experience, for riders, but it regards the driver’s welfare as someone else’s problem. Drivers are forced into a precarious hand-to-mouth existence, degrading our civilization for everyone.

Or how about the giant retailer that prides itself on offering the lowest prices to its shoppers, but it doesn’t pay its employees a living wage? The employees are forced to rely on second jobs and food stamps.

Machine learning algorithms, sometimes called AI, create significant externalities. Just letting the black box make decisions is an externality. Then when we trust those decisions, without having methods for oversight or verification, we create more externalities, compounding the problem. Most people are happy to abdicate their responsibilities to the algorithm. It seems easier. And it is. Because it’s an externality.

For example a company that makes software to automate hiring proudly uses machine learning to streamline the process. Its black box algorithms recommend candidates based on those you’ve hired in the past. The problem is that any racial, age, or gender prejudices are invisibly sustained, and nobody questions it. Nobody even sees it. Externalities hide in our point of view, our ignorance, our social norms, and the systems that we create and use.

In reality, everything is connected. There’s no such thing as an externality. If you regard something as external, you’re just bequeathing trouble to your descendants. You’re slamming a door on a fire, but it’s still burning in there and you’re leaving it for your children to put out.

And thirdly, we must ask, what time scale are we using? What is the lifespan of our actions, our products, and their effects. Our tools for peering ahead are weak, so we design based on the way things are right now, even though our products will live on in that uncertain future.

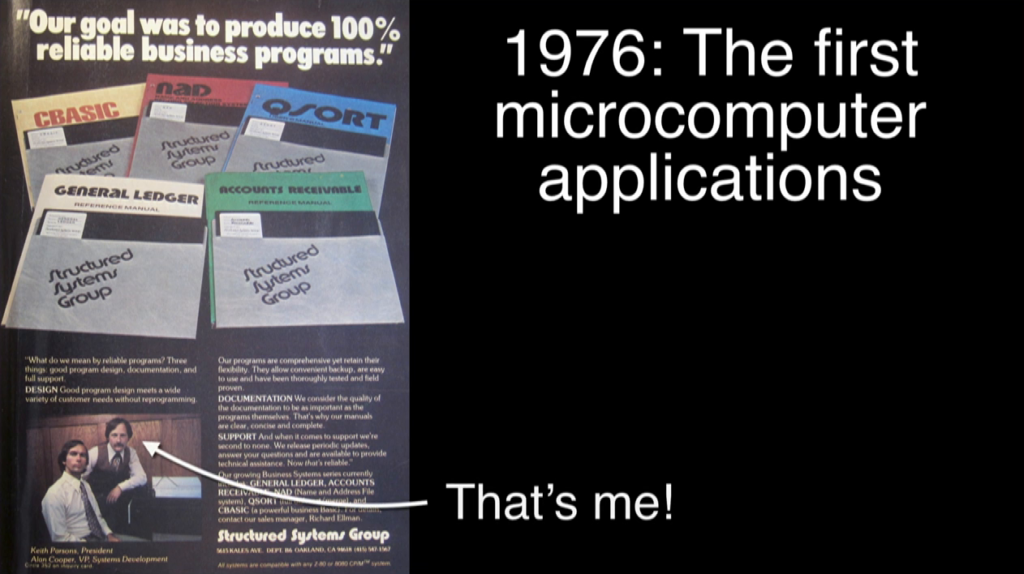

Now, I’m a perfect example of this. Software that I wrote in the mid 1970s conserved precious memory by using only two numbers for the year. The turn of the millennium, the year 2000, seemed very very far away. So I helped to create the Y2K bug. (I’m very proud of that, actually.)

All of our social systems bias us toward a presentist focus: capitalist markets, rapid technological advance, professional reward systems, and industrial management methods. You have to ask yourself, how will this be used in ten years? In thirty. When will it die? What will happen to its users? To be a good ancestor, we must look at the entire lifespan of our work.

I know I said that there were three considerations, but there’s a strong fourth one, too. Having established the three conduits for bad ancestry—assumptions, externalities, and timescale—we now need some tactical tools for ancestry thinking.

Because it’s a systems problem, individual people are rarely to blame. But people become representatives of the system. That is, the face of bad ancestry will usually be a person. So it takes some finesse to move in a positive direction without polarizing the situation. You can see from the USA’s current political situation how easy it is to slip into polarization.

First we need to understand that systems need constant work. John Gall’s theory of General Systemantics says that, “systems failure is an intrinsic feature of systems.” In other words, all systems go haywire, and will continue to go haywire, and only constant vigilance can keep those systems working in a positive direction. You can’t ignore systems. You have to ask questions about systems. You must probe constantly, deeply, and not accept rote answers.

And when you detect bad assumptions, ignored side-effects, or distortions of time, you have to ask those same questions of the others around you. You need to lead them through the thought process so they see the problem too. This is how you reveal the secret language of the system.

Ask about the external forces at work on the system. Who is outside of the system? What did they think of it? What leverage do they have? How might they use the system? Who is excluded from it?

Ask about the impact of the system. Who is affected by it? What other systems are affected? What are the indirect long-term effects? Who gets left behind?

Ask about the consent your system requires. Who agrees with what you are doing? Who disagrees? Who silently condones it? And who’s ignorant of it?

Ask who benefits from the system? Who makes money from it? Who loses money? Who gets promoted? And how does it affect the larger economy?

Ask about how the system can be misused. How can it be used to cheat, to steal, to confuse, to polarize, to alienate, to dominate, to terrify? Who might want to misuse it? What could they gain by it? Who could lose?

If you are asking questions like these regularly, you’re probably making a leaky boat.

Lately I’ve been talking a lot about what I call working backwards. It’s my preferred method of problem-solving. In the conventional world, gnarly challenges are always presented from within a context, a framework of thinking about the problem. The given framework is almost always too small of a window. Sometimes it’s the wrong window altogether. Viewed this way, your problems can seem inscrutable and unsolvable, a Gordian Knot.

Working backwards can be very effective in this situation. It’s similar to Edward de Bono’s notion of lateral thinking, and Taiichi Ohno’s idea of the 5 Whys. Instead of addressing the problem in its familiar surroundings, you step backwards and you examine the surroundings instead. Deconstructing and understanding the problem definition first is more productive than directly addressing the solution.

Typically you discover that the range of possible solutions first presented are too limiting, too conventional, and suppress innovation. When the situation forces you to choose between Option A or Option B, the choice is almost always Option C. If we don’t work backwards we tend to treat symptoms rather than causes. For example we clamor for a cure for cancer, but we ignore the search for what causes cancer. We institute recycling programs, but we don’t reduce our consumption of disposable plastic. We eat organic grains and meat, but we still grow them using profoundly unsustainable agricultural practices.

The difficulty presented by working backwards is that it typically violates established boundaries. The encompassing framework is often in a different field of thought and authority. Most people, when they detect such a boundary refuse to cross it. They say, “That’s not my responsibility.” But this is exactly what an externality looks like. Boundaries are even more counterproductive in tech.

A few years ago, a famous graphic circulated on the Web that said, “In 2015, Uber, the world’s largest taxi company, owns no vehicles. Facebook, the world’s most popular media owner, creates no content. Alibaba, the most valuable retailer, has no inventory. And Airbnb, the world’s largest accommodation provider, owns no real estate.”

The problem is that taxi companies are regulated by taxing and controlling vehicles. Media is controlled by regulating content. Retailing is controlled by taxing inventory. And accommodations by taxing rooms. All of the governmental checks and balances are side-stepped my business model innovation. These new business models are better than the old ones, but the new ideas short-circuit the controls we need to keep them from behaving like bad citizens, bad ancestors.

All business models have good sides and bad sides. We cannot protect ourselves against the bad parts by legislating symptoms and artifacts. Instead of legislating mechanism mechanisms, we have to legislate desired outcomes. The mechanisms may change frequently, but the outcomes remain very constant, and we need to step backwards to be good ancestors.

And when we step backwards, we see the big picture. But seeing it shows us that there’s a lot of deplorable stuff going on in the world today. And a lot of it is enabled and exacerbated by the high-tech products that we make. It might not be our fault, but it’s our responsibility to fix it.

One reaction to looking at the big picture is despair. When you realize the whole machine is going in the wrong direction, it’s easy to be overwhelmed with a fatalistic sense of doom. Another reaction to seeing this elephant is denial. It makes you want to just put your head back down and concentrate on the wireframes. But those paths are the Option A and the Option B of the problem, and I am committed to Option C. I want to fix the problem.

If you find yourself at the point in a product’s development where clearly unethical requests are made of you, when the boss asks you to lie, cheat, or steal, you’re too late for anything other than brinksmanship. I applaud you for your courage if you’re willing to put your job on the line for this, but it’s unfair for me to ask you to do it. My goal here is to arm you with practical, useful tools that will effectively turn the tech industry towards becoming a good ancestor. This is not a rebellion. Those tools will be more of a dialectic than a street protest. We can only play the long game here.

Our very powerlessness as individual practitioners makes us think that we can’t change the system. Unless of course we are one of the few empowered people. We imagine that powerful people take powerful actions. We picture the lone Tiananmen protester standing resolutely in front of a column of battle tanks, thus making us good ancestors. Similarly, we picture the CEO Jack Dorsey banning Nazis from Twitter and thus, in a stroke, making everything better.

This is a nice fantasy but it’s not actually true. The tanks in China had already been given the order to stop. Otherwise it would’ve driven right over the Tank Man. And Jack Dorsey is stuck in a dilemma he wishes desperately to get out of. If he bans Nazis, he asserts that censoring hate speech is Twitter’s responsibility. And if he doesn’t ban Nazis, he asserts that everyone will play nicely together. Because as soon as he bans a single Nazi he opens himself up to a tsunami of criticism and worse. There will be a wave of lawsuits from those who think he’s chosen too many Nazis, and those who think he’s chosen too few. The fact that his refusal to ban a Nazi is in itself a choice and opens him up to an equally large wave of criticism is why you don’t want to be in his shoes. Dorsey is at the end of a whip, jerking back and forth. There’s no good decision for him to make. He’s looking down the barrel of Option A and Option B. So he does what is easiest: nothing.

But you and I know that the only correct answer is Option C. Make no mistake about it, while Dorsey faces the twin evils of choices A and B, he isn’t an evil person. And he’s not guilty of any crime other than not thinking things through. And ultimately, that’s the solution: taking the time to think things through.

The more practitioners who do this, and the earlier in the creation process we do it, the more effective it becomes. Because there is no evil agenda, there’s no anti-evil agenda, either. This is all about our collective oversight and gentle intervention early in the process.

When we stand in the center of North America, watching the mile-wide Mississippi River flow by, our powerlessness to affect the mighty waterway is tangible. But if we ascend to the continental divide at the crest of the Rocky Mountains, where the river rises, it’s just a tiny rivulet, and we can divert the course of the Mississippi with a shovel.

This is the nature of how we divert the course of the tech industry. Neither Jack nor any of us are going to fix Twitter’s misbehavior with a single dramatic action. Twitter went off the rails one millimeter at a time, and the only way to put it back is with an equal number of tiny corrections. The way to vanquish evil is to find it at the source, in the headwaters, when it is a tiny and vulnerable thing.

I don’t mean to pick on Twitter or Jack Dorsey, but they’re a perfect example of the challenge that we face. Monitoring and curating an open public forum is hard, expensive work. Dorsey, as an idealistic Silicon Valley entrepreneur, believed that he could create a fully automated platform that would police itself. For that to work, he had to ignore the real-world behavior of anonymous strangers. He assumed that respectful public discourse would be self-perpetuating. He externalized responsibility for policing his forum. And he only thought about how things were, right now.

Like most libertarians, he failed to recognize how hard it is to be effortless. How much work goes into making sure that nasty people don’t shout down nice people. Because nice people never shout down nasty people. He’s been in denial about that behavior since day one.

Despite Jack Dorsey’s role as CEO of Twitter, he lacks the power to fix it. He is as unable to change the course of a mighty river as anyone else inside his company. He has power, but he lacks agency. Remarkably, the most junior practitioner at Twitter, while having none of Dorsey’s power has the exact same amount of agency. Now true, neither of them have much, but it’s not zero.

Power is the ability to change macro structures. Agency works on the micro level. Agency is local; power is global. Power is banning Nazis from Twitter. Agency is one person pointing out that there’s no mechanism in Twitter to identify suspected Nazis, and that there should be one. Power is being able to end homophobia; agency is one person coming out of the closet.

Agency in its embryonic state manifests simply as talking. We ask questions. We seek explanations. We point out the considerations. But the more you talk, the more you get heard. And the more you get heard, the more influence you have. Agency grows the more you exercise it.

Start by paying attention. This evolves into asking questions, which grows into discussions, followed by learning, then cooperation, then teamwork, and ultimately action. In this way we identify the assumptions we’re making, the externalities we’re creating, and the timeframes we’re working within.

When you start a dialogue with people you can make them think. You can show them a different point of view. Agency is a mirror you can hold up to your colleagues. It’s an amplifier, a newsfeed, a loudspeaker, a book, a friend. And you create a relationship. And you become more human in their mind. Admittedly this is a gradual process—an incremental process—but it’s the only viable process. And it works in for the long term.

In 2016, I spoke with activist blogger Anil Dash about the state of the tech industry. He posed a rhetorical question: Why aren’t we teaching ethics in engineering schools? His challenge really got under my skin and I couldn’t stop thinking about it. But ethics, ooh! There’s nothing more boring, useless, old, and pedantic. It’s hard to imagine a subject less interesting than technology and “the e word.”

Now fortuitously, I had recently been talking with folks at the engineering school at the University of California at Berkeley about teaching something there. Renato Verdugo, my new friend and collaborator with the great hair, agreed to help. And we just completed co-teaching a semester-long class called “Thinking Like a Good Ancestor” at the Jacobs Institute for Design Innovation on the Berkeley campus. Renato works for Google, and they generously supported our work.

We’re introducing our students to the fundamentals of how technology could lose its way. Of awareness and intentionality. We’re giving the students our taxonomy of assumptions, externalities, and time. Instead of focusing on how tech behaves badly, we’re focusing on how good tech is allowed to become bad. We’re not trying to patch the holes in the Titanic but prevent them from occurring in future tech. So we’re encouraging our students to exercise their personal agency. We expect these brilliant young students at Berkeley to take ancestry thinking out into the world. We expect them to make it a better place for all of our children.

Like those students, we are the practitioners. We are the makers. We are the ones who design, develop, and deploy software-powered experiences. At the start of this talk I asked you to imagine yourself as a tech practitioner witnessing your creations turned against our common good. Now I want you to imagine yourself creating products that can’t be turned towards evil. Products that won’t spy on you, won’t addict you, and won’t discriminate against you. More than anyone else, you have the power to create this reality. Because you have your hands on the technology. And I believe that the future is in the hands of the hands-on.

Ultimately, we the craftspeople who make the artifacts of the future have more effect on the world than the business executives, the politicians, and the investment community. We are like the keystone in the arch. Without us it all falls to the ground. While it may not be our fault that our products let evil leak in, it is certainly within our power to prevent it. The welfare of our children, and their children, is at stake, and taking care of our offspring is the best way to take care of ourselves.

We need to stand up, and stand together. Not in opposition but as a light shining in a dark room. Because if we don’t, we stand to lose everything. We need to harness our technology for good and prevent it from devouring us. I want you to understand the risks and know the inflection points. I want you to use your agency to sustain a dialogue with your colleagues. To work collectively and relentlessly. I want you to become an ancestry thinker. I want you to create products you could be proud of. Products that make the world a better place instead of just making yet another billionaire. I want you to change the vision of success in tech from making money to making a just and equitable world for everyone. You have the power to do this with your leadership, your agency, and with your hands-on. You can be a good ancestor. Thank you.