Introducer: Kevin Driscoll, that’s a name that’s well-known to many of us, not least because he is one of us, having graduated as you can see, Comparative Media Studies Masters Program in 2009. We’re pleased to have him around Boston again so that we can tap him for events like this, and previously for a bit of PhD career advice.

Speaking of PhDs, Kevin received his from USC, where he did his dissertation tracing the popular history of social computing through the dial-up bulletin board systems of the 1980s and 1990s, a topic that’s suspiciously like what he’ll be telling us about today. This talk will, according to the abstract that was circulated, “map out the generative conditions that gave rise to amateur computer networking at the end of the 1970s and trace the diffusion of BBSing across diverse cultural and geographic terrain during the 1980s.”

In his dissertation, Kevin takes a deep dive into the history, technology, and culture of bulletin board systems and their users in an attempt to reframe the history of the Internet away from ARPA and Licklider and a sort of highly-structured national enterprise towards something that takes into account the great impacts that amateur and hobbyist users had in the development of the Internet and its social systems as we know them today.

Kevin is now at MSR, where he continues his technocultural research. He’s also working on a manuscript based on his dissertation, but oriented around the theme of the pre-history of social media, and he’s designing a series of pedagogical tools that combine machine learning and communications studies through the process of data mining yourself, which is something I’m sure he’d be happy to answer some questions about after the talk.

We’re so pleased to have him here today to share his work with us. Please join me in welcoming Kevin Driscoll.

Kevin Driscoll: I have a question. I haven’t said a word yet. Is this a record? [Response inaudible.] Not the most substantive question we could’ve asked.

I’m really excited to be here, for many reasons, some of which you can probably imagine. But there’s an interesting looping back, to me, sitting in the room and listening to other people speak and trying to figure out how to conceptualize projects and how to do research and like, where a CMS person fits into the world of scholarly work. What do we learn as CMS students that we can then take into what I conceived of as more rigidly-structured disciplinary spaces like Com[?], although I was quickly disabused of that notion by people who are in things like sociology and history. But I think one thing that we bring when we do communications research from a CMS perspective is an attention to the boundaries and the edges and the little nooks and crannies where other literatures and other perspectives might creep in.

And so, we also are fond of asking ridiculously tricky questions. So here’s a question that drives out time today: Where did the Internet come from? And in order to answer that question, you would have to have a pretty clear idea of what you mean when you say “the Internet.” I suspect that if we were to poll everybody in the room, we would have a variety of different, sometimes contradictory, sometimes incompatible, sometimes overlapping, definitions of “the Internet.”

What I know about the Internet is that it matters a lot. Because when you ask people about Internet use, they will tell you that it matters a lot to them. Internet use ( Whatever that means. We’ll leave it open-ended for a minute longer.) is interwoven with people’s everyday lives, all their activities. And they will tell you if you ask them.

So of Internet users, nearly half say that it would be very hard to impossible to give up, and if you generalize by looking at the data, that means one in four of people in America say this. So Internet mattes. That’s true. And here’s what I think we mean when we talk about the Internet. All the things that we do with it.

So my guess is that you probably can’t read that in the back. But this axis right here is percentages. This is from the Pew Research Center data asking people what they do when they go online, and I’ve collapsed some of that data here to focus on the practices that they mention. What are the things that they do with the Internet? When they say “Internet use” what are the uses that they’re talking about? The things that you see are researching their hobbies, looking up information about the news, arguing about politics, getting health data, dating, finding jobs, figuring out how to fix something in their houses. All the things that people mention when they talk about the Internet are things that happen at this cultural level. It’s things that they do with it that the Internet facilitates, that it enables them to do.

And yet in spite of how deeply woven it is into people’s everyday lives in all these different areas of activity, by and large we collectively do not know very much about how it works, where it came from, what are the different components technically or politically that make it up? And that gets to the place like this where a pretty overwhelming majority of the users of the Internet, people who self-identified as Internet users, would be able to distinguish reliably between “Internet” and “World Wide Web.” They would just say that they are essentially the same thing.

This is constant across ages, too. This isn’t a story about generations. Young people are just as likely to have these ambiguous understandings of what they mean when they talk about Internet as older people. In fact, we’re starting to see some information that suggests that even the term “Internet” is falling out of use.

But I’m approaching this from a historical perspective. I asked at the beginning “where did the Internet come from?” So we know the Internet matters. People tell us that it matters, and they tell us all these different things about it. And they must have some idea where it came from. So really if you press people and you ask them, “Okay, where does it come from? Just tell me where you think it comes from.” they would be able to give you some kind of story. And there’s lots of different stories. And the stories that they tell matter a lot.

This is where this kind of CMS‑y perspective comes in, which is we can look at those stories, no matter how truthy they are or counterfactual they might be, and then think about what comes forth from that? If that’s what you think is the origin of the Internet, then what does it mean for you when you’re doing all those things that are on that list, when you’re sending emails to your family or something? How does the origin story play in here?

And we’ve been lucky recently to have opportunities to see this. In the discussion of net neutrality, of how we should regulate the Internet, what you see are key figures in a particular kind of hagiography of Internet history, who are invited to speak about how the Internet ought to work, how it ought to be regulated and governed. And when they do speak, whether it’s in a blog post or giving testimony, they will always remind you of their place in a particular historical setting, in a particular narrative.

So here you can see I’ve highlighted a part of this opening sentence to a blog post that appeared on the Google blog but authored by Vint Cerf, where he reminds you “when my colleagues and I proposed the technology behind the Internet” blah blah blah blah blah. So from a rhetorical point of view, you remind your listener—you are recalling a particular history and narrative that they might not even have, but you’re saying, “Come on, this is common knowledge. I’m the guy. And so here, this is what I’ve got to say.” This is not unique. We see it over and over in this conversation. “When I invented the web,” blah blah blah blah blah.

So origin stories matter. And the place to start, if you’re going to do work like this is to ask about what is that story that these guys are referring to? Because clearly they have some consensus within themselves about how this story’s shaped and who figures into it. Thom Streeter called that “the standard folklore.” He said yeah, if you look out there, there’s kind of a way of telling the story, it has certain actors, certain dramatic moments, conflicts that storied that are told over and over, and that forms something of a folklore. It has some basis in the experience of certain people form certain perspectives, but we shouldn’t assume that that is a universal history.

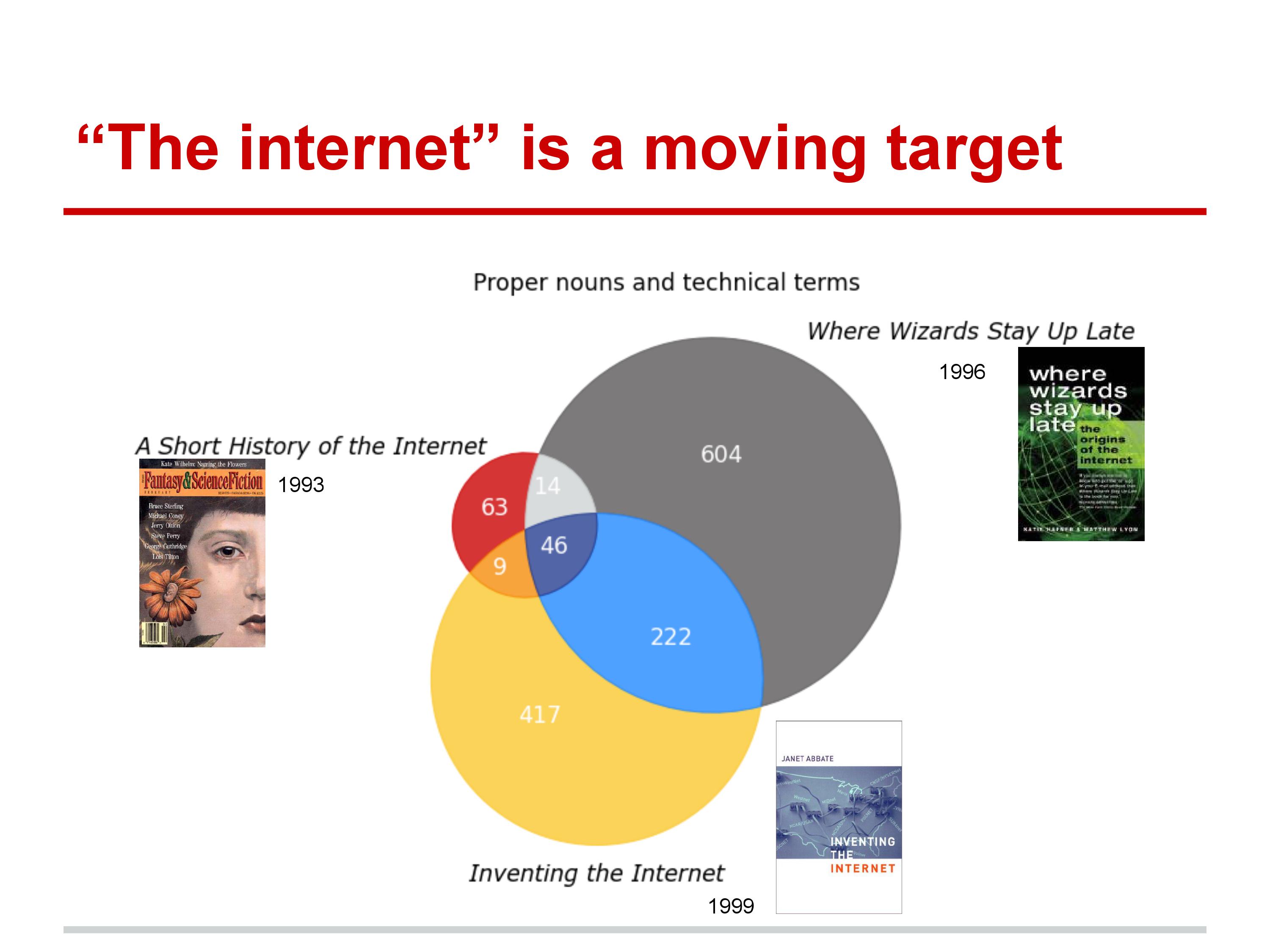

So here is an image that I throw up here. I’m not going to spend too much time on it because this is a little bit of a side-quest from our main story right now. But in the process of doing a dissertation you have lots of side-quests. So on this one I wanted to know about this standard folklore question. Here I’ve picked three representative texts that were from a corpus of texts that I looked at. The reason I choose these to share with you is because they really represent the best, the most widely-read, scholarly and popular books. These are regularly in print. You can usually get them at libraries. If you were a high school student who was going to write about where the Internet came from and you went to the town librarian, they may give you one of these two books. And this example you’ll see is dated 1993, before the commercialization of the net. This was a magazine, Fantasy & Science Fiction that published a column by multiple people, and one of those authors is science fiction writer Bruce Sterling, and he had begun historicizing the Net (as he was calling it at the time), before most people could even get on it. So you’ll see these numbers refer to concepts and as a way to explain this in shorthand, they are proper nouns, events, or institutions, or people. This overlap is showing how different ways of telling the story have certain features in common.

So the little kernel in the middle, the little chunk where they all meet, that’s the seed of the standard folklore. As I add more text to it, that thing more or less stays constant. You have certain figures, certain events, that they are there. So this notion of the standard folklore that Thom Streeter detected, we can see empirically how it is continually renewed over time. That as the story’s told with years passing in between, there are certain characters, certain features that come back around and around.

So if we go back to this origin story, the one represented by this standard folklore, we can kind of pull out some characteristics. Here I’m referring to it as the ARPANET origin story. Show me with your thumbs, if you are not familiar at all with this origin story you would put your thumb all the way down. If you know it super well and you could stand up here and tell everybody, then you would put your thumb all the way up. Give me a sense of your familiarity with this story so I can use my time wisely.

In the standard way of telling this origin story (and this is what we would see if we looked at those different tales) what you see it the development of this really interesting research network that brought together people from industry, from academia, from the military, who were doing computer networking research, and were particularly interested in building robust networks that could connect machines that were using different operating systems, different communications hardware and infrastructure, that would communicate over long distances, that would be reliable. And they developed the protocols and the technological habits that continue to undergird the global Internet today.

This table tells us a little bit about the cultural and technological characteristics of that milieu. We can see their host machines, the ones that are hosting the services and the content on the network, those tended to be mini computers or mainframes. So you can imagine that at MIT there are time-sharing computers like one computer with a room that has a bunch of terminals attached to it. That would be a host. And that one computer would be very expensive, and it would require significant expertise to manage.

The clients in this context are either what we would call “dumb terminals” meaning not really computers. A screen, a keyboard, and some communications hardware. Or they are workstations that are also used by say, a physicist who needs to be able to model things ad hoc. All of these folks share a certain kind of political economy. The money that pays for all this hardware (and probably their food and rent) comes from grants, it comes from their salaries that they get from universities, it kind of comes from a similar pot.

Likewise, they often have a social relationship that exists outside of this research. So it’s like the people you see at conferences every year. The people that you read their journal articles that you reviewed. There’s a kind of social homogeny that exists here that enables and facilitates this research. It’s critical to getting the work done. But it also means that when you go online on this network, you’re not expecting to encounter much difference. You go online and you kinda know who’s there, because you’ve met them before. Behind the handles it’s like, “That guy, I saw his paper. It was okay. Whatever.” You have some kind of fallback social relationship.

That’s kind of different than the way that I experience the Web and that I have for a while. When I go online I tend to experience a lot of difference. Contact with strangers, with people from backgrounds that are unknown to me. So I’m not seeing my social relationships necessarily reflected in this community.

We’ve said a little bit about what’s missing. Political economy, sociologically, we kinda have some dimensions through which when we look at this we don’t really see the Internet of today. One dimension that we do see is the technological dimension, so similar protocols and habits. But we really don’t see the social shape that we experience today there. And we definitely do not see all of these popular culture activities there. So you wouldn’t use the ARPANET to email with your parents, because they are not there. You wouldn’t be able to use it to buy tickets to the movies, because the movie thatre is not there. You couldn’t use it to provide customer support for your small business, because commercial activities are not allowed.

So here again at the layer of practices and culture, it’s not a satisfying origin story for us. It’s robust, and it is rich when it accounts for institutional and technological contributions, but it’s very thin on the side of culture. So where is popular culture, because you can’t write a book about the early Internet and not write about culture. Indeed, when we look at the best books about Internet history, they do their best to account for this. So one key recurring component of the standard folklore is the design of this early network, the ARPANET, was to enable researchers in one institution to access very expensive computing resources somewhere else. And you can see from a government point of view why that would be desirable. You just gave millions of dollars to the University of Illinois to put together a supercomputer and you’re like, “Well, it’d be pretty good if university researchers at other locations could use that computer.” So the justification for the network is really clear.

But in practice what happened is that everybody used it to exchange emails, which is kind of funny because it’s a really expensive way to have email, even at the time. One of the most popular uses for email is not one-to-one communications but many-to-many email forums or listservs, mailing lists. So a recurring story in the standard folklore is about the first email list to focus on popular culture, the SF-Lovers. I would never have thought of this anywhere else, but were there people in this room that were members of SF-Lovers? I feel like I always have to ask because one time there was somebody who was, and I was like okay, got to watch my words.

So here’s an email (obviously you’re not going to read this), but this pullquote in the middle that I’ve made quite large puts a real find point on the place of popular culture in the ARPANET. It was in hiding. It was not really a good idea to talk too much about the SF-Lovers. Which was so unfortunate, because if you look at the archive of this mailing list, people are thrilled at the chance to talk and debate about the issues being raised in science fiction during a real golden era of science fiction, a period of time where people are bringing in new ideas and new voices. They want to talk about it, people are dying to talk about it.

They’re saying, “Oh, wouldn’t it be great if we could give an account to this author? He lives in the town with me. I could teach him how to use it? Or maybe we could print out some of the best messages and make a fanzine and distribute it at this convention.” This person, who’s one of many who says this is like, “Folks, no. We cannot do that, because if the people in Congress who are currently in the process of dismantling all public institutions under the Reagan administration hear that we’re using the ARPANET to talk about science fiction, they are going to stop funding the ARPANET, so zip it.”

When new infrastructures and new networks became available to support this kind of activity, everybody moved. The SF-Lovers group, the community, persisted, but it stopped using ARPANET as its communication infrastructure because of a political-economic characteristic of that early network.

So I think I’ve got you convinced that the ARPANET is a really good story for telling us about technology and interesting ways that groups come together to build them, but it doesn’t tell us too much about culture. So where else do people go? If we’re polling people “Where did the Internet come from?” the other place that they will tell you is Silicon Valley.

Again, I was lucky during this project that I had an event occur where people expressed their counterfactual beliefs about the history of the Internet, and this was the death of Steve Jobs, where thousands of people thanked him for creating the Internet. Even President Obama stopped just a hair short of saying the same when he says that Steve Jobs, individually, “made the information revolution accessible and fun.”

In these moments, people are revealing some of their counterfactual history, and it kinda made sense. For some folks, they think okay, Bay Area…yeah there’s some cultural stuff going on there, and people value their egalitarian culture and that’s kinda like how the web works. So, yeah, it makes sense.

However, if we actually look at what products and services were being bought and sold in the time, if you purchased an Apple computer it did not come with any communications devices or hardware. That was an additional purchase, and kind of a hard sell. So for example, this is the packaging for modem for the Commodore 64, which was a very affordable home computer of the time. You can see they’re trying really hard to figure out how to market this. It’s a chicken and the egg problem, because in order for the network to be valuable, there have to be people already on the network that you want to talk to. So how do you get people on the network?

What we find is it’s a real word of mouth kind of thing, which is like, you go to your friend’s house; they’re already on; they show you; then you are convinced to get a modem. On the popular cultural level, it spreads in a real person-to-person way. So if we’re not talking about modems and their absence, then we’re kind of mischaracterizing this period. It raises yet another interesting historical question, which is if you went to the Apple store today and you bought a device and found out that it costs extra for it to have WiFi, it would be a preposterous this. It would be like it [costing] extra for your car to have brakes. The communications features are defining characteristics of how we imagine networked personal computing today. But they were not at this time, as evidenced by the fact that none of the major home computer brands shipped with communications hardware by default.

So not ARPANET, not Silicon Valley. Where can we go? And this is really my intervention. This is where the project begins to take a turn for the historical. My argument here is that if you want a rich origin story for all of these popular culture practices, the places you need to go are the small grass-roots bulletin board systems that dotted North America during the 1980s.

Tens of thousands of systems run mainly by volunteers and hobbyists out of their homes or the offices of their small businesses. Church basements, or by after-school clubs. This is the place where people first started to encounter difference, that they were arguing about politics, or that they were experimenting with online dating or ecommerce, or all the defining activities of the contemporary social web.

This is sort of how I conceptualize this big messy project. We want to know the role of computer hobbyists. What are the material contributions that they made to building the networks that we’ve come to think of as the Internet? Then we also want to know the implications of this story. If you restore this story, and this story had as much of a prominent place in the popular imaginary as the ARPANET story, what would that mean for us, politically? What new political possiblities would become available?

So here’s how I did it. The first thing is that there’s a reason that people haven’t done this work already, and it’s not because it’s not interesting. Almost every historical book about the Internet will mention bulletin board systems along the way. Because everybody knows it matters. The problem is that it was institutionally not very highly valued. In other words, from the perspective of somebody who has access to those awesomely powerful military-funded machines, it’s just not that interesting to look at dial-up bulletin board systems. So the folks that are leaving behind a lot of traces that are well-organized and placed in archives and libraries, those folks just weren’t messing with these systems.

In fact, there’s evidence from when bulletin board systems got really big they would have conventions and invite folks who were big computer networking researchers to come speak, and the people would admit they had never called a bulletin board system, ten or fifteen years after they had become a dominant form of hobby networking.

That’s one problem. Another problem is that the key thing that we care about, which is the messages, the chats, the files, the things that people were actually doing on the boards, were highly ephemeral. So even if you wanted to collect it, it was really hard to collect it. People didn’t have the storage media needed. They just didn’t have big hard drives. It was really costly to print out messages, and it’s hard to know what would’ve been worth keeping.

Like, now we want to know the everyday experience of a bulletin board, but from the contemporary moment of looking at the bulletin board system as a system operator, how do you choose which messages are worth saving and not? Indeded, when I look at the code of the bulletin board system host software, often it had a set number of messages that could be stored, and when you got to the last one it just went back and wrote over the first one. So the histories were being written over by the very activity. The more lively the board is, the more likely it is that we don’t have a record of all that went on there.

So we’ve got a challenge. But fortunately, the same kind of popular culture, the same technical cultures that we’re interested in documenting, have also grown to include a kind of amateur preservationist activity.

This is a snapshot from a ham radio swap meet. There are ham radio swap meets in most big cities. There’s one at MIT on the campus. This is a place where a distributed archive of hobby technologies comes together. It’s where it is manifest. There are no finding aids, and there’s no easy indexes for us to use, but when we go to these places we meet people with expertise and experience and excitement, who have an interest in finding and preserving these sorts of materials. So in a way these are the kinds of archives that I have to work with, and I presume some of you soon will work with when you see how important and interesting this research is. And this is reflected also in online spaces where people build web sites that serve as kind of nodes in this distributed archive, some of which are just lingering. They were contemporaneous with Internet bulletin board systems of the 1990s, and some of which are more reflective.

So if you see this top left corner, the BBS Mates, that’s a database of bulletin board systems organized by their names and their area codes, their dial-up phone numbers. In the About page for it, the person says, “Did you lose contact with your friends? Here’s a place for you to find each other again.” So there is some memory work that’s only recently started to happen that we can interface with as researchers.

But the interface has some tricky ethical territory that comes along with it. It’s hard to know from a researcher point of view how we relate to this distributed archive. The relationship to a library archive is a little bit more clear.

But here’s a picture that I took from someone’s home looking at just a piece of the collection that they have amassed. When I encountered this I was feeling like I should turn away and run, because it was frightening. It was like, whoa, there’s a lot of stuff here and it is not organized and I don’t know what to do about it. Then what I learned through spending time is that there are ways that these materials circulate that have labor attached to them. So there become certain figures in these communities who are bearing a very large burden, who are kind of serving a middle role between the formal collecting institutions catching up and starting to build and house these things, and their initial production.

So in the case of this person, part of the way that their collection grew so large is that they got a reputation in the community for someone who values and [preserves] these materials. And other people would send them unsolicited boxes of stuff, along with notes that said things like, “I know that you will take care of this. It was so important to me I held onto it for twenty years.” Just putting this incredible emotional burden on this person to be the steward of a community’s history.

This is another place that I visited that is full of computer ephemera. It is a storage container that was funded through the crowdfunding platform Kickstarter, and this is a picture of me inside of it where it was below freezing and we were going through all these materials. While I was there and I was literally freezing, to the point there was blood coming out of my fingers, I was thinking about materiality, sure. But also, what is my role in that moment? Am I just a researcher doing archival work? Because we’re having conversation while we’re working, there’s a level of intimacy that’s going on here that was unexpected to me. I didn’t think of this as an interview or as an ethnographic moment. So this is a challenge that we will have to continue to take up.

And this slide is a bit of an invitation because we’re in a local institution, so some of the materials that I’ve collected are now in a very small bookshelf that’s in the 1 Memorial Drive building nearby. So if any of you are interested in this work, you should let me know and you can come and visit and take a look at some of the materials that I’ve collected.

So I described a lot of work. Some of it was mine, a lot of it was other people’s, but it enabled me to put together the pieces for what I think is a pretty compelling alternative origin story.

All origin stories need to have some kind of starting moment, a context within which everything became possible. For us I locate that in the mid-1970s, for a few different reasons, some cultural, some political, some economic, some technological.

Here is a blown-up snapshot of the standard telephone jack. It may be difficult to rememeber, if you can remember this far at all, but this was an innovation and it only came about through serious political intervention on the part of the government into how the telephone companies worked. It was only til the mid-1970s if you lived in a big city that when you rented a new apartment you could assume that there would be a standardized phone jack on the wall for you to plug into. Prior to that, you had to call somebody from the telephone company to come and wire you up. This was part and parcel of a number of moves that were around this juncture between the period of time when the telephone network was a regulated monopoly and the period of time where it became de-regulated. And both sides of that history are essential for creating the conditions within which dial-up bulletin boards became possible.

So when we think about the mid-1970s, we think about a project that had public interest at its heart which built an infrastructure for communication that connected almost all of the homes in the US. Not only did it connect them, it also gave us a very robust and easy to understand addressing system, which was the phone numbers. The phone numbers are really interesting; they’re not random. You have the area code and the exchange, which gives you information about how much it will cost to call that number, and where on the map that number is located. So if someone gives you a phone number, you learn over time, or you can look up in a book, that’s in Wyoming, and this is down the street, and this costs a lost, and this doesn’t cost anything. So we got this really interesting system, and then through de-regulation it became possible to experiment with that network. So not only did we have a network that connected almost everybody, but it worked in a really reliable way and it was now legal for you without any prior approval to just connect some new toy to it, something that you built yourself or you bought, so that’s why we got fax machines and answer machines, and the modem. But this goes by without most people noticing it. It’s like somewhat more convenient, but if you’re just a telephone user it’s like, okay ther’s now a differnt plug in the wall.

This is more interesting. This is the poster from Smokey and the Bandit, by all rights a massive hit in popular cinema. If you look in the logo for Smokey and the Bandit, you see the microphone for a CB radio. Also in the painting, with all that’s going on, Burt Reynolds is still holding on to the CB radio with his left hand and a Coors in his right hand as he’s trucking from Texarkana carrying all of the beer back to Texas where a big party will take place.

So the CB radio has shifted amateur telecommunications from this kind of organized rule-based amateur radio place where people are very interested in doing it right and doing it well, to a pretty chaotic wild space of cowboys and truckers and muscle car drivers who are out there just talking, evading police, trying to do all kinds of things. And the boom of the CB radio happens across multiple areas of popular culture. So there’s films like Smokey and the Bandit and Convoy, but there’s also songs on the radio that have the sounds of the CB radio in it. So for your everyday consumer of popular culture, the notion that technologies could be used for communicating with other people at a distance in a way that’s fun, that’s pleasurable and maybe a little bit subversive, is a pretty mass idea at this time. And it’s reflected in the literature of the technical hobbies.

This book is titled Hobby Computers are Here, and it is published by 73, which was a publisher of amateur radio books and magazines, and edited by Wayne Green, who provides his call sign. Green was publishing columns in amateur radio magazines entreating the readers to get involved in hobby computing, saying, “This makes a lot of sense. If you like radio, you’re going to like computing.” Then he went on to found a number of magazines, including Byte, which became one of the most widely read and distributed hobby computing magazines. So from that original moment, the connection between telecommunications, amateur telecommunications, and hobby computing was pretty clear.

Here’s a group of people that capitalized on it quite early. In February of 1978 there was like two friends who were members of the same computer club, and they got snowed in and decided to do a project. This was the [Great] Blizzard of 1978 winter. The project they conceived of was similar to other projects that were getting under way by different computer clubs, but they called it CBBS, which is helpful for us because they borrowed the rhetorical structure of computerization of something, which was very common for the two decades prior. There had been the computerization of finance, and the computerization of air travel, and computerization of voting. And here there is computerization of bulletin boards.

So they kind of paired this super high-tech thing, computerization, with one of the most low-tech communication technologies that would be familiar to everyday folks: the community bulletin board that’s in the local grocery store or the church, that anybody can post a message on. The messages can be all sorts of things, they could be art, they could be announcing events and other things. They imagined a computer based system, just sitting in one of their homes connected to the wall, and it invites you to come in and leave messages. And I’m very intentional with my use of the verb “invite” here because they really did conceive of it almost like an open house. The callers that were calling into the bulletin board were visiting the home of Randy Suess, and likewise they kind of expected them to follow certain social protocol like, “Don’t be a jerk and mess up the place. I’m welcoming you to take control of my computer temporarily.”

So there’s this kind of informal friendliness. And this appealed to a lot of folks who are already in little networks of computer hobbyists, local computer groups and things like that. So quickly, bulletin board systems proliferated, particularly in metropolitan areas where the area codes were large enough that you could make a lot of cheap calls. So it’s actually interesting because if you’re in a super-dense area, they were chopping up the areas so you couldn’t call as far with a toll-free call. So you may be living in a place like this hypothetical person where you have two bulletin boards nearby. You could have different accounts on them, different names, you could have a totally different personality. So the bulletin board notion, this network of small networks, an internet of sorts, gave people a lot of flexibility about how they presented themselves and how they engaged different communities.

This is a chart (and I use this chart instead of making my own because this was made by Jason Scott, who’s a well-known enthusiast of bulletin boards and also a documentary filmmaker who made a documentary about them) and he estimates that there are over 90,000 BBSs at peak time. But this chart also invites us to speculate, because a bulletin could be three friends who just for fun make a bulletin board system and hang out a shingle, or it could be three thousand people who are routinely calling in and trading software and doing all kinds of things.

So it’s another historical challenge for us to estimate how many people were involved in this. But I think we get to this point where we can think of this as a parallel world. There are parallel tracks here where the ARPANET is developing really robust ways of doing internetworking over long distance with various types of media. Sometimes it goes over the wires, sometimes it goes over the airwaves, sometimes it goes to a satellite. And at the same time there are hobbyists who are using just the telephone network that had been in place for decades, but they’re developing all this social technology on top of it, figuring out how you should moderate the system, administer it, who’s in charge, who makes the rules, what are good rules, what are bad rules, how do you kick people off if they’re being a jerk, how do you get more cool people to join you? All of that is happening on this kind of people’s Internet layer.

So we can expand our table and put them together, and we’ll come back to the implications of this in a moment. But the people at the time conceived of it as this other space, and owning a modem and using a modem was really a mark of distinction. People would say, “I’m a modemer.I’m not just any computer user, I have a modem. I’m part of the modem world. I go modeming. I do this thing that’s different, that’s unusual.” And so the modem world had certain features that would be recognizable regardless of where you happened to be in the network.

One is that there were low barriers to getting involved, but also to leaving. So if you didn’t like the way it was going, you could get out. Part of that has to do with political economy. There’s symmetry between the hosts and the clients in these networks. So whereas in ARPANET the hosts are really expensive minicomputers and the clients are dumb terminals in this time-sharing paradigm, on these bulletin board systems, the computer you use to call a bulletin board could be used to host a bulletin board. So there is a real parity there.

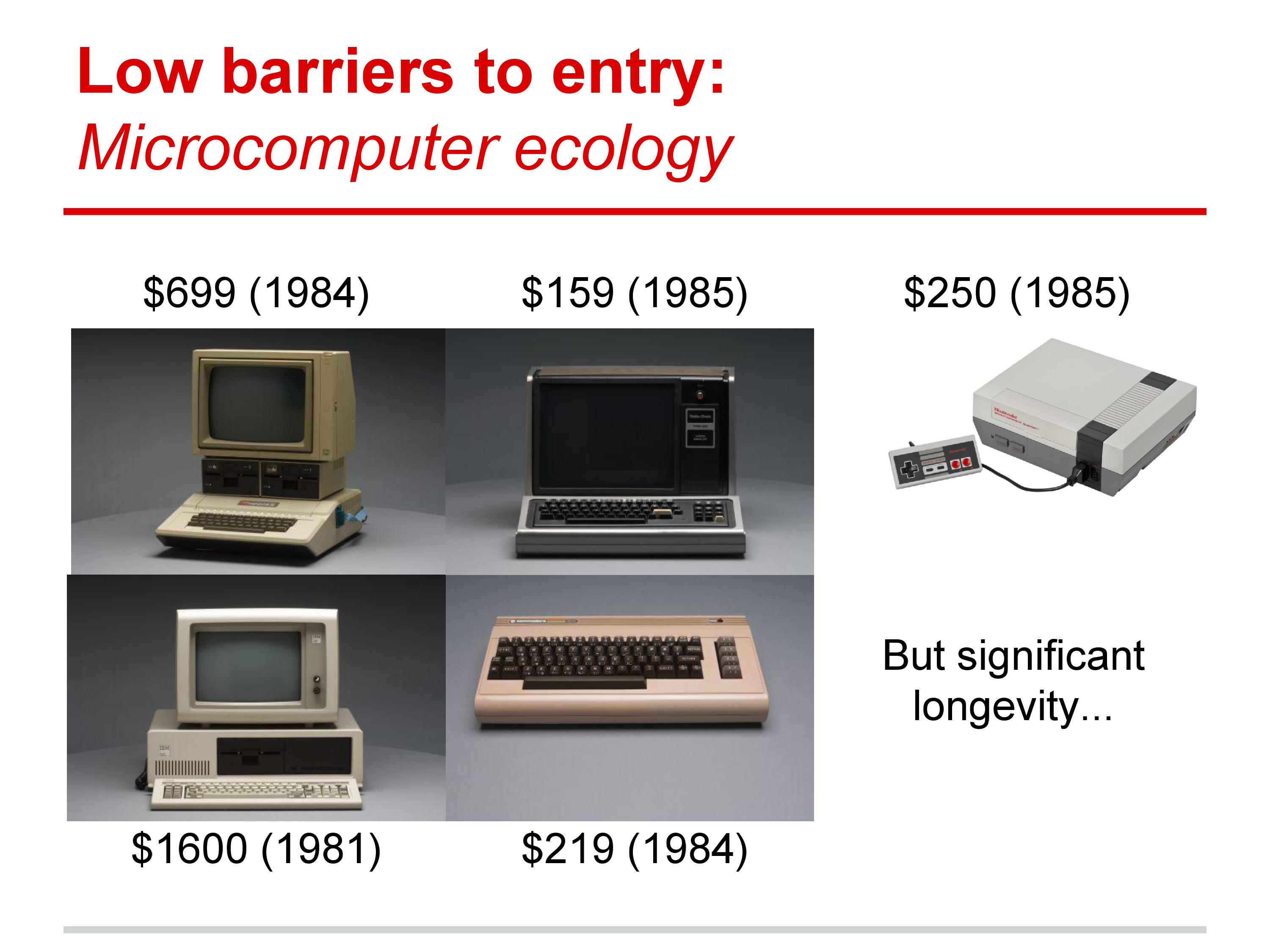

I put these numbers here to give some context for when I say that things are affordable. Because when I say affordable I do mean a very conventional notion of what middle-class 1980s American looks like. But we tend to collapse all the computers together when the pricing was an area of economic interest. It wasn’t clear how to price these machines yet. So you can see this is the Nintendo Entertainment System, which few people people thing of as an elite technology; it seems like quite a populist system. And yet it was more expensive at launch than the Commodore 64, which also was a game-playing device but had these additional affordances of being a thing you could learn to program on or connect to bulletin boards. There were, of course, very expensive systems like the IBM PC, which traded on the business reputation of the IBM brand, and the Apple PC which did aspire to be this very expensive elite cultural product. So both of those cost as much as a used car would.

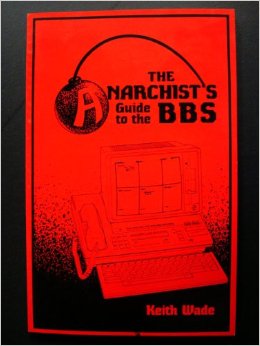

This low cost had caught the interest of folks who build networks. One group of those are political activists. Here is a book that caused some controversy upon its release among folks who hoped that BBSes would achieve some Wall Street legitimacy, The Anarchist’s Guide to the BBS, where the author says that the BBS is the “five hundred dollar anarchy machine” and specifically mentions that you should go to thrift shops or businesses that are closing and see if you can buy old machines. He’s like, the central activity you want to do here is chatting and sharing messages with people, and he even says “amber letters read as nicely as red, blue, and purple, and a monochrome system is much cheaper.”

So there was this awareness that even when we do this kind of economic look at the history and look at the prices, there’s a second life that a lot of machines had that’s invisible from the industry-level metrics that are available. This low cost led to a distribution of ownership over the infrastructure.

[The T.A.R.D.I.S BBS] is a BBS that I came across during my archival period of research. This one ran for ten years on the same Appke II, but yet it was lively and it was beloved by its users. It was not interested in technical innovation but the four people who founded it, two men and two women, were really interested in creating a system that was accessible by many definitions of the word. Accessible both in terms of disability, and accessible to people from different social strata. So when they realized that women who were going on other bulletin board systems where they were soundly outnumbered (this was an overwhelmingly male pursuit) they created a women’s-only area on their bulletin board system, and in order to enter the area you had to be verified by a voice phone call or a face-to-face meeting with the women who were in charge of moderating the area.

In reflecting on this period of time, the founder of the board said to me, “Still to this day I have no idea what went on in there.” It’s interesting for him to say that considering that the machine was in his home. So there’s the disk whirring away, and there’s phone calls coming in, and people are accessing this women-only area, and he cannot see it because he has locked himself out of it programmatically. This is a system that people remember fondly because of that. It also encouraged them to meet offline. Many of the people here lived around Indianapolis and they would get together monthly for pizza parties and stuff like that.

So there was a real move for the online and offline distinction to be continuous. That reflects an affordance here that’s not immediately obvious, which is because of those low barriers and because there were people owning different nodes of the network and managing them differently, you had a lot more autonomy over how you behaved and how you experienced this system. When you visit the home of somebody who’s hosting a BBS, there is nothing abstract about where you’re data is stored. You know where it is, it’s literally on that brown desk in the corner of that room in that house, and I know the address and I might’ve even visited it. Which is such a contrast to the way that our data is evaporated into a kind of cloud imaginary that we are hopefully thinking is ubiquitous. There were advantages to knowing exactly where your data was stored. So you might choose to conduct certain types of communication on this node that you wouldn’t on that node, and vice versa.

And of course this was extremely important to communities who were using these systems who were otherwise facing oppression, or were marginalized, or their communication was being suppressed in other systmatic sorts of ways. The gay and lesbian BBS list, which was compiled and circulated monthly, was organized by area code so that you could easily locate a system that is near to you. You can think of lots of reasons why it would be helpful to know if a system that is geared towards gay and lesbian users in the 1980s is nearby. Not only is it cheaper to call (you have an economic reason to do it) but there’s also a chance that those people are dealing with conditions that are unique to that region. There may be laws in place that are not in place in other states, there may be commercials on TV that are offensive to you and you want to talk to people that are nearby about it. So it creates this safe space to go where you can assume that the other people there are facing similar regionally-specific conditions.

So with these kind of characteristics in mind, let’s go back just as a way to conclude and think about this recent period we’ve gone through of saving the Internet. Here’s an image of activists protesting outside the FCC in advance of the ruling about net neutrality, who are saying keep the Internet free. And of course after listening to be gab for 45 minutes, you’re asking yourselves, “Oh well, what is the Internet that you’re talking about here?” Is it the Internet of bulletin board systems with all these locally-specific, tightly-managed, very hands-on face-to-face type relationships, or is it the highly-centralized, vertically-integrated walled gardens that we tend to commit our very valuable intimate communications to today?

I’m going to go one step further and show a material link that exists between these two worlds. Some of the biggest bulletin board systems that were thriving in the mid-1990s were providing some limited Internet services. So you could dial in and then you could send email. Sometimes you could use what’s known as SLIP and create a kind of IP connection so you could use Mosaic or Netscape or something like that.

And what’s so funny is that many of these bulletin board operators saw that there was potential to make money with this new information superhighway bubble. So they would create corporations and give them much more staid names. So Crazy House BBS became the first Internet Service Provider to serve the west coast of Florida around St. Petersburg [as “Florida Network Technologies, Inc.”], and they definitely didn’t market themselves as “Crazy House” when they did that. It was a business-friendly ISP. They grew through this period, and the bulletin board system stayed, but it also facilitated this Internet access. So the big entrenched telecom companies, it was not a priority to bring high-speed Internet access to St. Petersburg. So the guys that ran Crazy House were the Internet. There’s no distinction or rhetorical moves that we have to make. They provided Internet service to the communities—large communities—along the Gulf Coast.

And there was money in it, because the big ISPs when they decided to come in, would see that this small grassroots ISP was already there, and it made a lot more sense to buy them out. There’s lots of good economic reasons to have these huge monopolistic ISPs because they can take advantage of network externalities and other sorts of things. But what that moment of acquisition does is that it ruptures the clear material and cultural connection between the 1980s grassroots systems and the communication systems we value now.

So here we are back at our keeping the Internet free. And we can move forward with our activism and our advocacy with this enlarged imaginary, and we can ask for an Internet that looks a little more like the column on the right. Where there’s a place for community-run systems. Where nodes can be operated by small and medium-size enterprises. And where there can be more locally-specific control and moderation.

So I’ve given you this provocative picture, and let’s talk about it for the time that we have left.

Thanks.

[It seems no microphone was passed around, so audience questions were extremely faint to inaudible. Kevin’s responses are included below, and are generally detailed enough to get a sense of what the questions were.]

Response 1: That’s a really good question, and there’s two answers. There’s implicit connections, which is almost like reinventing the wheel, in a way. I think for example, Yik Yak recreates some of the regionally-specific conversation that happens on a BBS, but it’s not because the founders of Yik Yak used BBSes. They were children at the time that this was really thriving.

That’s one answer. Another answer is where people moved and they took their experiences forward. So there you can see it more in the discussion of larger-scale systems where…and in a way this happens more in places where the BBS period lingered longer— So I have Google alerts for tons of keywords related to my research, and something that’s really striking is that there’s a lot more memory work happening among Russian-language computer hobbyists than among English-language computer hobbyists of remembering some of the big BBS networks.

Even simple things such as putting the Russian-language Wikipedia pages for certain big networks and the English-language pages side by side, there is so much more memory work going on. So what happened there is sometimes people use the exact same handles or names from their dial-up systems in a web-based forum, or a subreddit, or something like that. They have a continuous identity that hops as the infrastructures beneath them change.

So yeah, there’s some implicit and some explicit connections.

Response 2: I’m interested in Reddit, and Lana [Swartz] and I have been talking about Reddit a lot recently. Lana, who’s another CMS alumn and I have a paper that is about interest-driven message boards, like independent web sites that people go to talk about a shared interest. It could be sports; in the case we looked at it was about gem collectors. [“ ‘I hate your politics but I love your diamonds’: The Web-based Interest-driven Messageboard as DIY Infrastructure” (Google Books preview) in DIY Citizenship: Critical Making and Social Media] There, we suggested that it was theoretically useful to imagine all web forums as a single socio-technical phenomenon that we called “the decentralized social web.” That gave us a reasonably-shaped unit of analysis to compare that against something like Facebook.

What’s interesting to me about Reddit is that it occupies this middle space, where to me Reddit is like economic enclosure of that decentralized activity. Reddit provides the tools for you to start a forum and it looks a lot like bulletin board systems. In fact one of the places I go to see retrocomputing enthusiasts talk about BBSes is on a subreddit called r/bbs, which is just too recursive for me to manage.

But there you see that could be administered in a decentralized sort of way that allows some of the full autonomy of the dial-up system, but there’s an economic reason that it is fully enclosed and owned, and that’s partly to centralize all the data in a common store that’s accessible to only a small number of people. So I can see why that is happening, and I don’t expect that to stop soon. But I do expect that people will start to fragment their conversations across many different platforms.

And that’s not really a prediction because that already happens. You look at your phone and you have like nine apps that you can send me a message on, and you decide in the moment, ” Well, Kevin and I talk about sports on this app and we talk about work on GMail and so I click on that and I send the message.” I have many different channels, and channels have different symbolic meaning attached to them, and the messages that come through them are shot through and laden with those meanings.

Response 3: It’s interesting from both a critical art and technology point of view, and scholarship of maybe ten or fifteen years ago, people were really excited about peer-to-peer, and it seemed like peer-to-peer was going to be the answer. Peer-to-peer systems are generally described as distributed, meaning every node can connect to every other node, that’s like a radically distributed system. I’m pretty critical about my choice of “decentralized,” which is there are still centers, it’s just that the centers happen at a much more local scale, and there are many many more centers, and there are redundancies among the centers so that if one of them takes a turn away from your cultural values, you can opt to choose a different center. So in a way, we used to think a lot about barriers of entry and we want to lower the barriers of entry. That was a big concern for all media scholarship. We want to see like, we went from film to video and the barriers of entry went down with some costs associated with them.

But now I’m really concerned about barriers to exit, because the barrier to exit for something like Facebook is ridiculously high. So tons of people stay no matter how unhappy they are with the way that the system is governed and the poor stewardship of our public culture that happens in that place. So I want to think about systems that have lower barriers to exit, even if their barriers to entry are a little bit higher, which really is the case for some of these kind of things.

Response 4: So the term “network” is generative for scholars because it has mobility across all of these different domains, and so we can imagine that any humans that lived in as densely-settled communities as we do now had social networks that proliferated the way that yours have. The difference that we face now (and this almost bridges to your other question) is that they are often inscribed in socio-technical systems in ways that they might not have been before. So you might have met the basketball group informally and you agree each time you meet when to meet the next time and share information about what Ben Gay sub-brand is the best. But now that conversation can carry through in between meetings, and it leaves behind digital traces of a sort.

So there is a question then about what media you choose to use for different networks. That’s a little bit what I’m pointing to with having the different apps and things like that. Some of the social networks that you are engaged with will opt to use one system or another, and it does seem to me that there are cases where people’s social networks have moments of breakdown or conflict over disagreements over which medium to use to have their conversations on. My interest then is really more about both the technical affordances and values associated with those media, and also the political-economic dimensions of them. So if your basketball ball group is having small but not insignificant economic externalities for this corporation that is sending its profits overseas so as not to pay the taxes that will then make sure that there are nets on the hoops at the public basketball ball court, that has some significance that is historically unusual.

So that would be one answer. The other thing about history, which I love talking about with hobbyists because some of what drives the computer hobbyists is a sense of loss, which is like, “This thing was so important and I was part of this big network and it was huge and there was thousands of people there, I swear.” And you will even see when you start looking at say, blog posts that are about violations of privacy on Facebook, I hesitate to say that there is a law, but I would almost predict that when the comments get above a thousand or so, someone will eventually say, “Boy, I wish we could go back to those BBSes, ha ha. I bet I’m the only one who remembers that.”

There’s this very unusual social memory thing that’s happening with folks there. So sometimes the people that would be likely to utter something like that would be like, “Oh, we’re losing it but at least you’re engaged in documenting or saving it.” And it’s like, we might be losing it but we’re losing it a lot less than people who are in disadvantaged positions of various kinds ever did before. So doing social history of computers of the 80s, it’s like we’ve got tons of stuff.

Response 5: That’s kind of what I’m saying. Things that never left a trace do leave traces now, and in fact overwhelming traces. From the point of view of if there was a professional archivist here, they would say— Actually I have an empirical quote. I visited another archive that was the Microsoft corporate archive, and the archivist there told me that from her perspective managing very very large institutional archives, her biggest skill that she developed was what to throw away, because every time they released a product, there was like fifty language versions of it. So did she need to preserve Excel for each different market that they sold it in, or was it okay to have one version, or should she make a digital copy of each and just save one box? Very unusual kinds of archival questions which are not scarcity-driven, but are driven by abundance.

So that’s from a corporate history point of view. But from a social history point of view, it’s similar. There’s a lot of evidence, but the shape of the evidence is very unusual. Thinking about this is almost a statistical way, we’ve got these bits of data and we’re kind of trying to fit them to a curve but we’re missing all these different parts. An example of that is the materials that I rely on are often preserved by video game enthusiasts whose sole goal is to be able to play old games. And on the road to being able to play an old game, they may produce some knowledge or technology or software that I can then use to recreate or simulate an old bulletin board system. That was not at all the goal of that community. So if people like that become aware that BBSes are important, they may come across the software and save it, but by and large you can go and get a torrent that has every single Commodore 64 game known to man, but try to find all the Commodore 64 communications software and it’s a much trickier terrain.

So there’s some interesting stuff that goes on in terms of what gets saved, and it doesn’t fit previous models of deciding what was worth saving, but it doesn’t mean that it’s wholly egalitarian or universal, either. There is a dialectic at play in the Internet at large, which is the Internet is forever and it will embarrass you thirty years from now and it never forgets. That’s one strand of conversation. And the other strand is you can’t find things twice and it’s gone and there’s too much stuff and it’s infoglut. These are polar opposite, totally contradicting perspectives that people hold at once in their mind as they use the… They both can be true.

Response 6: There’s generations within this BBSing community, and there was a clear period around 1990 where there was a young people/teenager/hacker land, people who are sharing a lot of games and stuff, and then there’s older folks who maybe had a business interest or they’d been talking to the same people about Doctor Who for ten years and they didn’t want to teach somebody how to use a bulletin board. And people intuitively knew this is a board for adults, and this is a board for teens and some of the teens of the time would have said “this is boring” to go to this place. “All the people talk about their jobs” or whatever.

however, there’s an interesting space which people called slam boards or flame boards where you would just go and talk smack to each other. It seems to have recurred across many different regional communities, that teens would just create a bulletin board system. And creating a bulletin board system can be as simple as running the software for a few hours and calling your friend and being like, “Okay, call me in fifteen minutes,” then hanging up and starting it then you can talk on the board. So the definition of a running board is actually pretty loose.

There were even games and other sorts of things. Formalized games that encouraged board versus board wars where people, almost grafitti crews fighting with each other go and try to crash the other person’s board. Actually a sad end to the T.A.R.D.I.S. BBS that I mentioned was that there were some local kids who figured out a way that you could break their bulletin board and take it offline, and it’s almost too perfect for me to tell. I’m afraid you won’t believe me that this is the story, which is that newer modems were so fast that when they connected, the handshake sound confused the modem that was being used by the T.A.R.D.I.S. BBS and would make it hang up and then crash the board. So merely calling at it with a 9600 bps modem would crash this board by a quirk, and at that time the person who was running it didn’t have the technical expertise or the time to fix this problem.

Kids broke it and took it down week after week, and he even called their parents and was like, “Please stop your child from doing this,” and the parents got really mad at him and said no. Then were were threats of police and stuff. Eventually the callers assumed that the board went offline so they stopped calling, and that was this petering out point for that community. It’s really sad.

So there were these things where sometimes technology and social norms met in this case. So flooding a chat room is an example of that. Or uploading disgusting pictures of victims of crimes or something like that, where you’re intentionally taking advantage of the affordances of the system in order to make it work less well for other users.

And there are text files that circulated that were somewhere between an FAQ or a guide that suggested things you might do as a system operator or moderator to prevent those things from happening, and verifying callers by voice was a really common one. In fact, later bulletin board system software implemented the feature, which is really neat, where you’d call in and say, “I’d like to become a member of this community,” and you’d just leave your name and phone number. Then when the person who ran the board came home there’d be a queue waiting that these three people called in, and then you just call them like, “Oh yeah, I’m Jim. The board is about video games.” Then they would get brought in and people at the time didn’t really speculate explicitly about this, but I think it’s a reasonable assumption to make that there is something that occurs with people in a social/psychological way that if they’ve heard your voice it alters the experience rather than just coming in anonymously and you have no orientation into what the purpose of that system is at all.

And there are a small number (I have them in my little library, if anybody’s curious about this moderation stuff) of books that are about running bulletin board systems. So this one is how to create your bulletin board system and it’s one of the first ones. It includes a lot of code to bring it online, but says nothing about how to get callers or how to treat them. Then within ten years, later books that came out that are much longer and look kind of like they’re in the genre of How to Learn Java in 20 Days-type books, those would have all kinds of stuff about advertising and how to charge fees. There’s a ton of discussion about pricing and payment and how to receive payment and pay the bills, because it wasn’t free to run a bulletin board system. Then they sometimes include things, sometimes in a legalistic way and then occasionally more in a hands-on socio-cultural kind of way, on how to run a board, like what it means to be a system operator beyond the technical stuff.

Response 7: Scoping it down to North America was just something I had to do to make the project manageable, and in fact it’s a very transnational story and like I mentioned with that anecdote about Wikipedia pages, in many ways the story is much richer in Europe and especially Eastern Europe. Part of the reason is that, as I understand it, behind the Iron Curtain in certain countries telecommunications developed differently. So there was not the same private investment in building high-speed data and networks. So in the US, high-speed data networks were being built by MCI and these newly-deregulated long line telecom companies. So when it became politically feasible to interconnect the systems, it was like “the wires are already on the poles, so we can do that” whereas in other places the early encounter of the net is bulletin board systems.

For example, it was a bulletin board system network that brought Internet email to South Africa. This we know for sure. Then there’s more stories that I’ve been having a more difficult time substantiating, but a kind of folklore among the bulletin board system enthusiasts is that there were NGOs who were in different places who were exchanging health information that was coming out of US research institutions, but was not yet available in places like Northern Africa for reasons of government censorship and surveillance. So in a way the bulletin board system architecture enabled some amount of subversive communication because the connections are intermittent.

Now I’m getting into the weeds a little bit of what would be a whole other hour, but there was a way of internetworking the bulletin board systems where the boards themselves would call each other and so in the middle of the night two boards would call and then exchange messages and synchronize their forums. What that means was if you were at Board A, you could talk to someone at Board B without having to make that long-distance call. That technology was extended to trans-oceanic links, so there were a small number of bulletin boards on the East Coast of the US that made calls into Western Europe and then the files and messages dispersed. And getting to David’s comparison, that structure, that way of making a communication network is exactly as a hundred years before when amateur radio operators created trans-continental messaging networks using store and forward links, which is basically it takes a few hops to get your message there, but the message travels across the cheapest route. So you always want your message to go through the cheapest link.

There were also some wealthy people that were involved that just footed the bill. There was a very wealthy person who was very concerned about the health of queer people and the ability of queer people in different parts of the country and in different parts of the world to get access to information about HIV and AIDS. They used their personal wealth to call into the Department of Health and access new health papers each week, and then they used their personal funds to call a whole bunch of other nodes and redistribute the information. There is a really great story there and I’m looking forward to reading somebody else’s book that is about it, but you’re totally right that it is tricky to talk about a thing in its global implications without losing a lot of really important detail around the edges.

Response 8: You’re pointing to a really interesting aspect of denaturalizing the way that the technologies work now. I think often about the smartphone as this really interesting radio that has multiple antennas, and it can transmit and receive on a surprising array of frequencies. I can talk on Bluetooth, and I can talk to the 3G networks, and I can talk to WiFi, and that’s pretty wild, that I can jump between those different types of radio communications. But there’s no standard app in my phone that when I want to transfer something it suggests to me the optimal medium to use in that moment. There’s no way for me to create some logics in it that would say, if I’m messaging with this person wait until I’m on this type of network, because I don’t want this message to go over T‑Mobile; I only want it to go over the MIT network, or something like that.

So in a way, what we’re talking about is maybe detecting preferences that say “You only ever message these people when you’re on WiFi. Should I delay them?” This is not a priority in terms of our design, and it isn’t about Moore’s Law, or creating faster networks or something like that. It’s about organizing the technologies that we already have in a different way so that when they communicate, the types of communication are reflecting some of the values of the users differently.

In a way it does point back to this idealized research network that was being developed in the 1980s that really did hope that it would work in a certain way, but it’s hard to have a communications network that crosses huge, vast tracts of land that doesn’t involve any corporations at all. And especially politically intractable in the 1980, when we were in the project of creating more for-profit enterprises within the world of telecommunications. So I mean, I love that way of identifying the conflicts between the ideal way that the network ought to work, the way that it does, and how sometimes there can be mismatches there, but they work fine, and they kind of get along fine. It seems like that was happening for most of the early history of the Internet.

The turning point really is when almost all Internet users in North America shifted from a mix of different ways of getting onto the Internet to just four or five different broadband Internet service providers. Then we fundamentally changed what we mean by “Internet” and we’re de-emphasizing the network. A lot of our communications never leave our internet service provider. We never actually do the inter-networking of going to other networks. We’re always inside of Comcast or whatever it is.

So yeah, I’m very curious about futures that have more inter-networking involved in them, where I know that my communications are traveling across different kinds of networks and I have some sense of the values and purposes associated with those different communication media.

Response 9: All sexting, all the time. Exclusively sexting. [More from the audience member.] It’s very interesting to play the role of both scholar and political activist or advocate. So from a political point of view, save the Internet. I want to have net neutrality rules in place.

But from a scholarly point of view, I can see that political campaign made strange bedfellows, where I’m sitting alongside of major media corporations. That’s weird. I wouldn’t have thought that that would necessarily have happened. And why should the Internet be neutral for television companies to send television shows to me? We already have networks and means of sending television shows around, so why is the use of the Internet for television now crowding out all of those popular cultural activities that you just mentioned, be it sexting or texting with a family member?

So I do think that there is a way that we can operate on both levels, and there’s expediency and instrumental practical realities that we have to confront as political actors, and there’s also theoretical dreams and imagination that we have to bring into the picture to imagine what an ideal system would be. And in an ideal system, Netflix is seen as an extension of television, it is a mass medium, it is not the same as point-to-point communication. YouTube seems to occupy different spaces, but YouTube caters through its structures and policies to entrenched mass media companies.

This isn’t to say that mass media companies are bad or something like that, but they are fundamentally different political actors than individuals or non-profit groups or church organizations, and treating them all the same seems to be a radical shift from the way we’ve managed media in the past.

Response 10: I think sexting is extremely meaningful communication. I don’t know what to say about that. I would not want a cessation of sexual content online. And it’s funny, I’m engaged in another project about Minitel, which was a French state-run network that’s often remembered as a highly-censored network, but the state had no interest in the sexual activities of its users and in fact that was the first major system for online sexual content. And lots of people had really nice affairs through that, I’m sure, and they wrote songs about it that you could hear in the club and stuff like that. So, people are going to use the media for whatever social needs that they have. It could be transferring data files, it could be finding somebody to hook up with. Those are both really important valuable uses. So I don’t know what will come from that.

Thanks.

Further Reference

Original event listing at the MIT CMS/W site.