Herald: The next talk is by David Graeber, and he’s an author, activist and anthropologist. And he will be speaking about his talk “From Managerial Feudalism to the Revolt of the Caring Class”. Please give him a great round of applause and welcome him to the stage. [applause]

David Graeber: Hello. Hi. It’s great to be here. I wanted to talk—I’ve been in a very bad mood this last week, owing to the results of the election in the UK. And I’ve been thinking very hard about what happened, and how to maintain hope.

I don’t usually use visual aids but I actually assembled them. And the thing— What I want to talk about a little bit is what seems to be happening in the world politically that we have results like what just happened in the UK. And why there is nonetheless reason for hope. Which I really think there is. In a way, this is very much a blip. Probably the most— But there’s a strategic lesson to be learned, I think, speaking as someone who’s been involved in attempts to transform the world…at least for the last twenty years since I was involved with the global justice movement. I think that there’s a real…lack of strategic understanding. That there’s a—vast shifts that’re happening in the world in terms of central class dynamics that the populist right is taking advantage of, and the left is really being caught flat-footed on. So, I want to make a case of what seems to be going wrong and what we could do about it.

First of all, in terms of despairing. I was very much at the point of despairing. So many people put so much work, that I know, into trying to turn around the situation, there seemed to be a genuine possibility of a broad social transformation in England. And when we got the results, I mean…there was a kind of sense of shock.

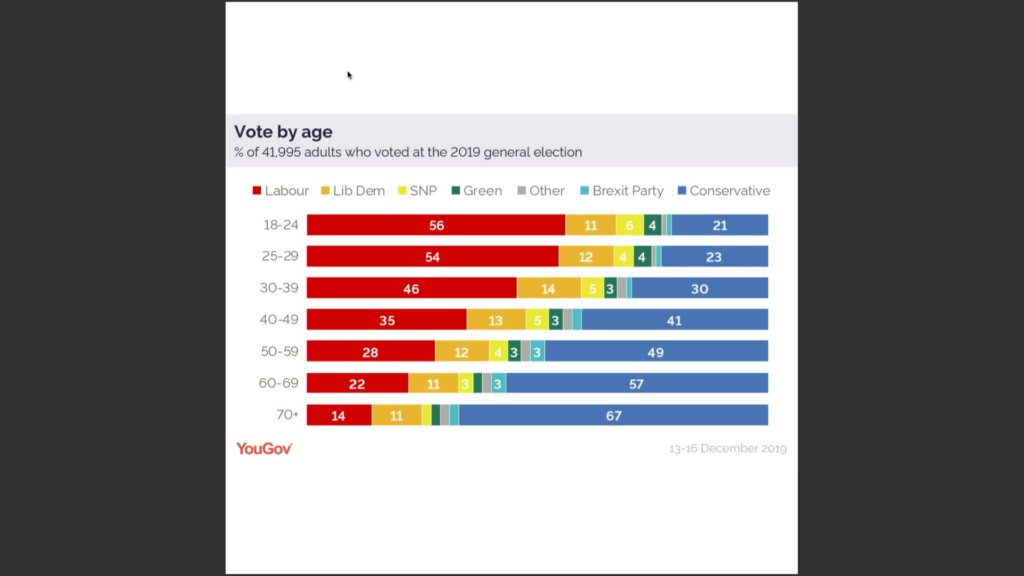

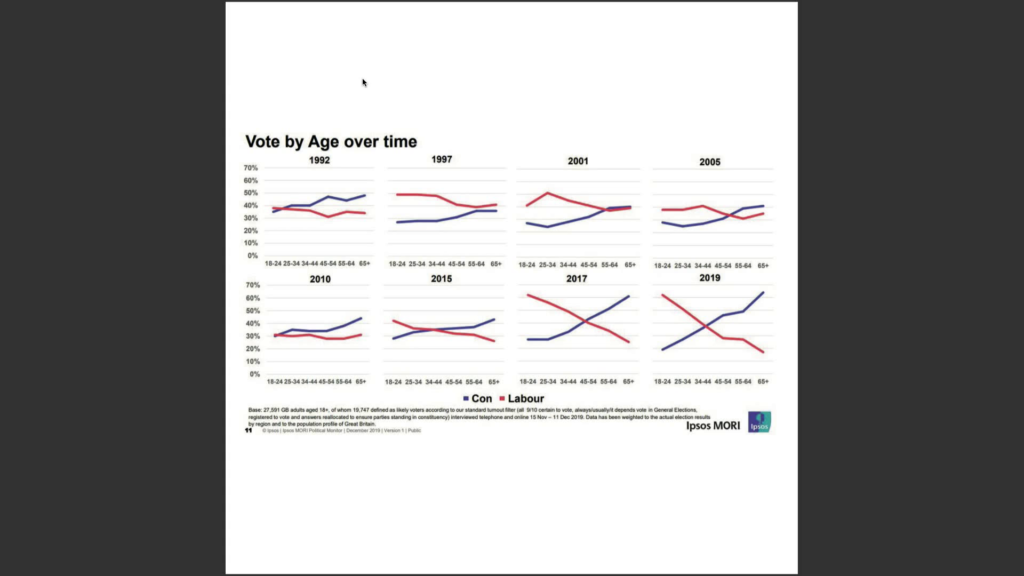

But actually, if you look at the breakdown of the vote, for example, it doesn’t look too great for the right in the long run. Basically, the younger you are, the more determined you are to kick the Tories out. The core— Actually I’ve never seen numbers quite like this. The electoral base of the right wing is almost exclusively old. And the older you are, the more likely you are to vote conservative. Which is really kind of amazing. Because it means that the electoral base of the right is literally dying off. A process which they’re actually expediting by defunding healthcare in every way possible. [laughs]

And normally you’d say, “Oh yes, so what. As people get older, they become more conservative.” But there’s every reason to think that that’s not actually happening this time around. Especially because traditionally, people who either had been apathetic or had voted for the left who eventually end up voting for the right do so at the point when they get a mortgage, or when they get a sort of secure job with room for promotion and therefore feel they have a stake in the system.

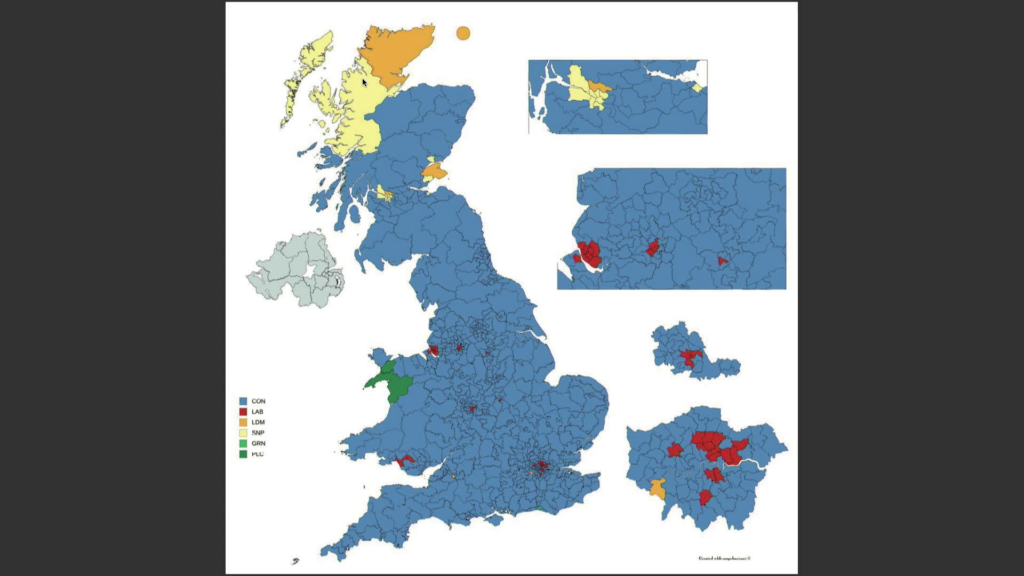

Well, that’s precisely what’s not happening to this new generation. So if that’s the case, the right wing’s actually in the long run in real trouble. And to show you just how remarkable the situation is, someone put together a electoral map of the UK, showing what it would look like if only people over sixty-five voted, and what it would look like if only people under twenty-five voted. Here’s the first one.

Blue is Tory. If only people over sixty-five voted, I believe there would be four or five Labor MPs, but otherwise entirely conservative. Now here’s the map if only people under twenty-five voted.

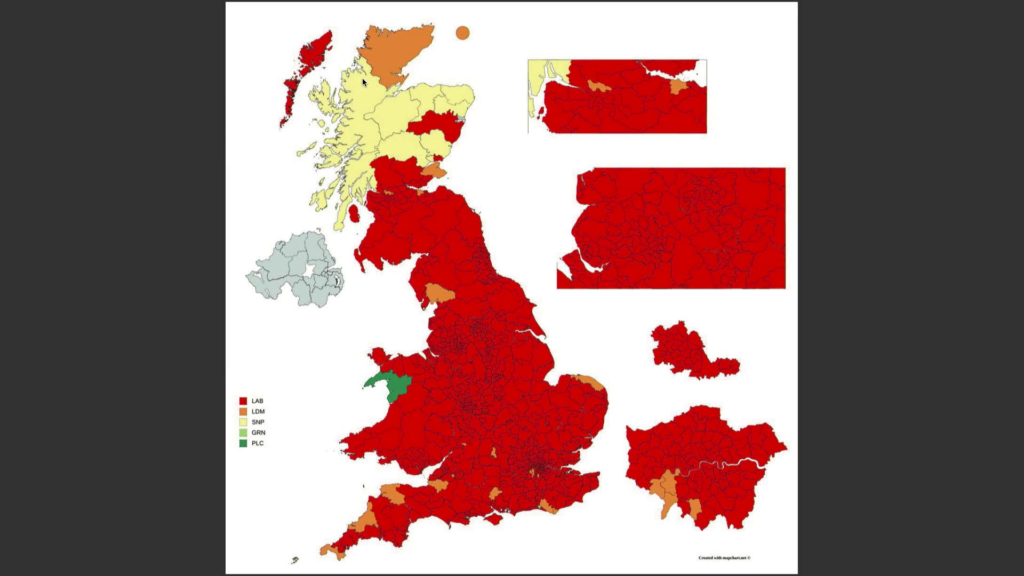

There would be no Tory MPs at all. There might be a few Liberal Dems and Welsh candidates, and Scottish ones.

And in fact this is a relatively recent phenomena. Here’s…if you look at the divergence, you know, it really is just the last few years it started to look like that. So something has happened that like almost all young people coming in are voting not just for the left but for the radical left. I mean, Corbyn ran on a platform that just two or three years before would’ve been considered completely insane and you know, just falling off the political spectrum altogether. Yet the vast majority of young people voted for it.

The problem is that in a situation like this, the swing voters are the sort of middle-aged people. And for some reason middle-aged people broke right. The question is why did that happen? And I’ve been trying to figure that out.

Now, in order to do so I think we need to really think hard about what has been happening to social class relations. And the conclusion that I came to is that essentially the left is applying an outdated paradigm. You know, they’re still thinking in terms of bosses and workers and a kind of old-fashioned industrial sense. Where what’s really going on is that for most people the key class opposition is caregivers versus managers. And essentially, leftist parties are trying to represent both sides at the same time, but they’re really dominated by the latter.

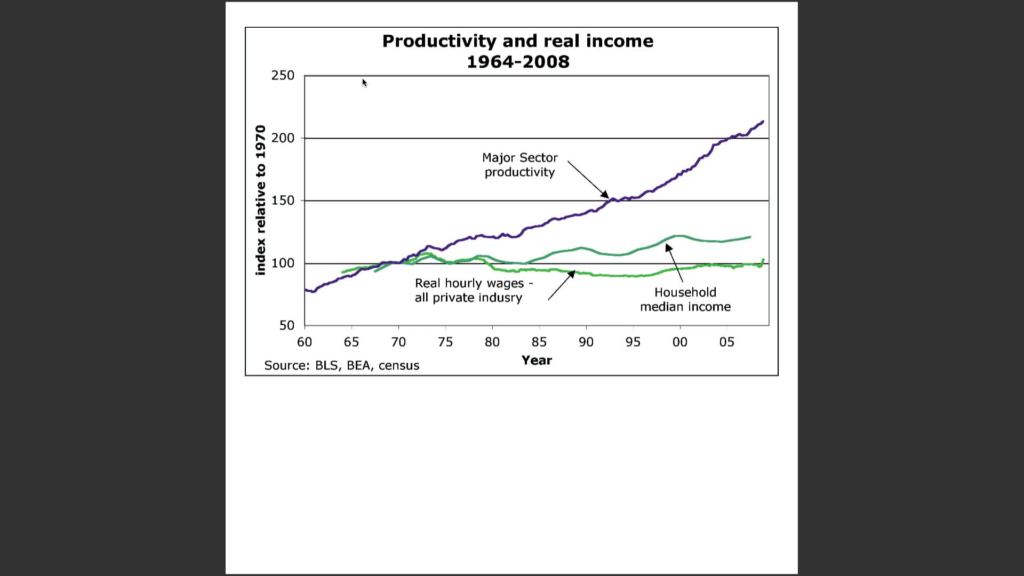

Now I’m going to go through some basic political economy stuff in way of background. And this is a key sort of statistic, which is the kind of thing we were looking at when we first started talking about the 99% and the 1% at the beginning of Occupy Wall Street. Essentially, until the mid-70s, there was a sort of understanding—between 1945 and 1975, say. There was an understanding that as productivity increases, wages will go up, too. And they largely went up together. This only takes it from 1960, but it goes back to the 40s. More productivity goes up; a cut of that went to the workers. Around 1975 or so it really splits. And since then, if you see what’s going on here, productivity keeps going up and up and up and up, whereas wages remain flat.

So the question is what happens to all that money from the increased productivity? Basically it goes to 1% of the population. And that’s what we were talking about when we talked about the 1%. The other point, which was key to the notion of the 99 and 1% when we developed that, was that the 1% are also the people who make all the political campaign contributions. These statistics are from America, which has an unusually corrupt system. But pretty much all of them— Bribery is basically legal in America. But essentially it’s the same people who are making all the campaign contributions who have collected all of the profits from increased productivity, all the increased wealth. And essentially they’re the people who managed to turn their wealth into power and their power back into wealth.

So, who are these people, and how does this relate to changes in the workforce? Well, the interesting thing that I discovered when I started looking into this is that the rhetoric we used to describe the changes in class structure since the 70s is really deceptive. Because you know, since…really since the 80s, everybody’s been talking about the service economy. We’re shifting from an industrial to a service economy.

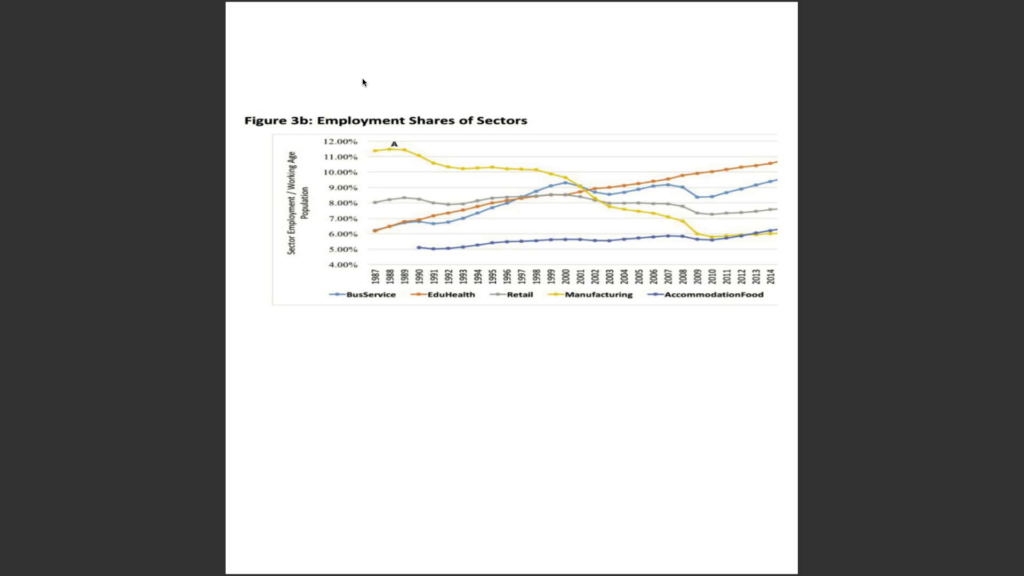

And the image that people have is that you know, we’ve all gone from being factory workers to serving each other lattes and pressing each other’s trousers and so forth. But actually, if you look at the actual numbers of people in retail, people who’re actually serving food… I don’t have a detailed breakdown here. But they remain pretty much constant. And in fact I’ve seen figures going back 150 years which show that it’s pretty much 15% of the population that does that sort of thing. It has been for you know, over a century. It doesn’t really change. It goes up and down a little bit. But basically, the amount of people who’re actually providing services—haircuts, things like that—is pretty much the same as it’s always been.

What’s actually happened is that you’ve had a growth of two areas. One is providing, what I would call caregiving work. And I would include education and health. But basically taking care of other people in one way or another. In the statistics you have to look at education and health because they don’t really have a category of caregiving in economic statistics.

On the other hand you have administration. And the number of people who’re doing clerical, administrative, and supervisory work has gone up enormously. To some degree…according to some accounts, it’s gone up from maybe 20% of the population in say, UK or America in 1900, to 40, 50, 60%. I mean even a majority of workers.

Now, the interesting thing about that is that huge numbers of those people seem to be convinced they really aren’t doing anything. Essentially if their jobs didn’t exist it would make no difference at all. It’s almost as if they were just making up jobs in offices to keep people busy. And this was the theme of my book I wrote on bullshit jobs.

And just to describe the genesis of that book, essentially I don’t actually myself come from a professional background. So, as a professor I constantly meet people. Sort of…spouses of my colleagues, the sort of people you meet when you’re socializing with people with professional backgrounds. I keep running into people at parties who work in offices and saying, “Well—” You know I’m an anthropologist, right. I keep asking, “Well what do you actually do? I mean, what does a person who is a management consultant, you know, actually do all day?”

And very often they will say, “Well, not much.”

Or you ask people—you’ll say, “I am an anthropologist, what do you do?” and they’ll say, “Well, nothing really.”

And you know, you think they’re just being modest, you know. So, you kind of interrogate them…a few drinks later they admit that actually they meant that literally. They actually do nothing all day. You know, they sit around and they adjust their Facebook profiles. They play computer games. Sometimes they’ll take a couple calls a day. Sometimes they’ll take a couple calls a week. Sometimes they’re just there in case something goes wrong. Sometimes they just don’t do anything at all. And you ask, “Well, does your supervisor know this?” And they say, “You know, I often wonder. I think they do.”

So I began to wonder, how many people are there like this? Is this some weird coincidence that I just happen to run into people like this all the time? What section of the workforce is actually doing nothing all day?

So I wrote a little article. I had a friend who was starting a radical magazine, said, “Can you write something provocative? You know, something you’d never be able to get published elsewhere?” So I wrote a little piece called On the Phenomenon of Bullshit Jobs, where I suggested that you know, back in the 30s, Keynes wrote this famous essay predicting that by around now we would all be working fifteen-hour weeks because automation would like, get rid of most manual labor. And if you look at the jobs that existed in the 30s you know, that’s true.

So I said well maybe what’s happened is the reason we’re not working fifteen-hour weeks is they just made up bullshit jobs, just to keep us all working. And I wrote this piece you know, as kind of a joke, right?

Within a week, this thing had been translated into fifteen different languages. It was circulating around the world. The server kept crashing, it was getting millions and millions of hits. And I was like oh my god, you mean it’s true? And eventually someone did a survey. YouGov, I think. And they discovered that of people in the UK, 37% agreed that if their job didn’t exist, either it would make no difference whatsoever or the world might be a slightly better place.

And I thought about that. Like, what must that do to the human soul? Can you imagine that? You know, waking up every morning and going to work thinking that you’re doing absolutely nothing if. No wonder people are angry and depressed.

And I thought about it and you know, it explains a lot of social phenomena that if people are just pretending to work all day. And you know, it actually really touched me. And it’s strange because I come from a working class background myself, so you’d think that, you know, oh great, so lots of people are paid to do nothing all day and get good salaries. Like, my heart bleeds, you know?

But actually if you think about it, it’s actually a horrible situation. Because as someone who has had a real job knows, the very very worst part of any real job is when you finish the job but you have to keep working because your boss’ll get mad, you know. You have to pretend to work because it’s somebody else’s time. It’s a very strange metaphysical notion we have in our society, that someone else can own your time. So since you’re on the clock, you have to keep working or pretend to be. Make up something to look busy.

Well apparently, at least a third of people in our society, that’s all they do. Their entire job consists of just looking busy to make somebody else happy. That must be horrible. That must…

And it made a lot of political sense. Why is it that people seem to resent teachers or auto workers? After the 2008 crash, the people who really had to take a hit were teachers and auto workers. And there was a lot of people saying, “Well, these guys are making twenty-five dollars an hour, you know?” Well yeah. That’s…they’re providing a useful service—they’re making cars. You’re American, you’re supposed to like cars. You know, cars is what makes you what you are if you’re American. How would they resent auto workers?

And I realized that it only makes sense if there’s huge proportions of the population who aren’t doing anything, and were totally miserable, and are basically saying like, “Yeah, but…you get to teach kids. You get to make stuff. You get to [make] cars. And then you want vacations, too? That’s not fair,” you know? It’s almost as if the suffering that you experience doing nothing all day is itself a sort of validation of…it’s like this kind of hair shirt that makes you—justifies your salary. And I truly hear people saying this logic all the time, that well teachers you know, I mean, they get to teach kids. You don’t want people to pay ’em too much. You don’t want people who’re just interested in money taking care of our kids, do we?

Which is odd because you never hear people say…you never want greedy people, people who are just interested in money taking care of our money so therefore you shouldn’t pay bankers so much. Though you’d think that would be a more serious problem, right? Yeah, so there is this idea that if you’re doing something that actually serves a purpose, somehow…that should be enough. You shouldn’t get a lot of money for it.

Alright. So, as a result of this, there is actually an inverse relationship—that I don’t have actual numbers for this—but there’s actually an inverse relationship, and I have seen economic confirmation of this, between how socially beneficial your work is—how obviously your work benefits other people—and how much you get paid. And there’s a few exceptions, like doctors, which everybody talks about. But generally speaking the more useful your work the less they’ll pay you for it.

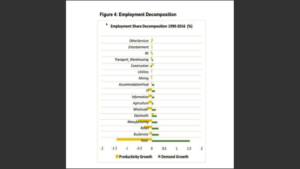

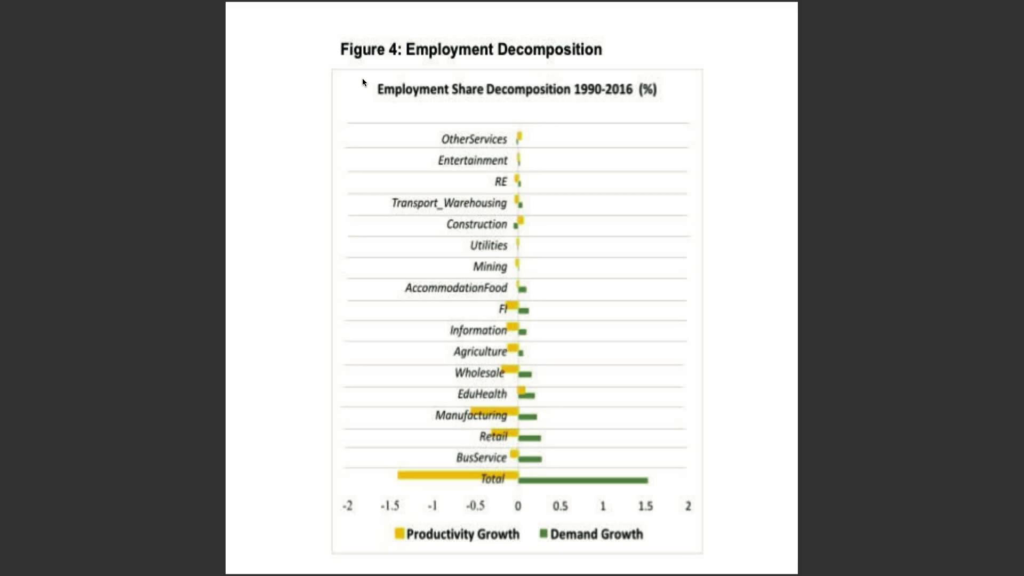

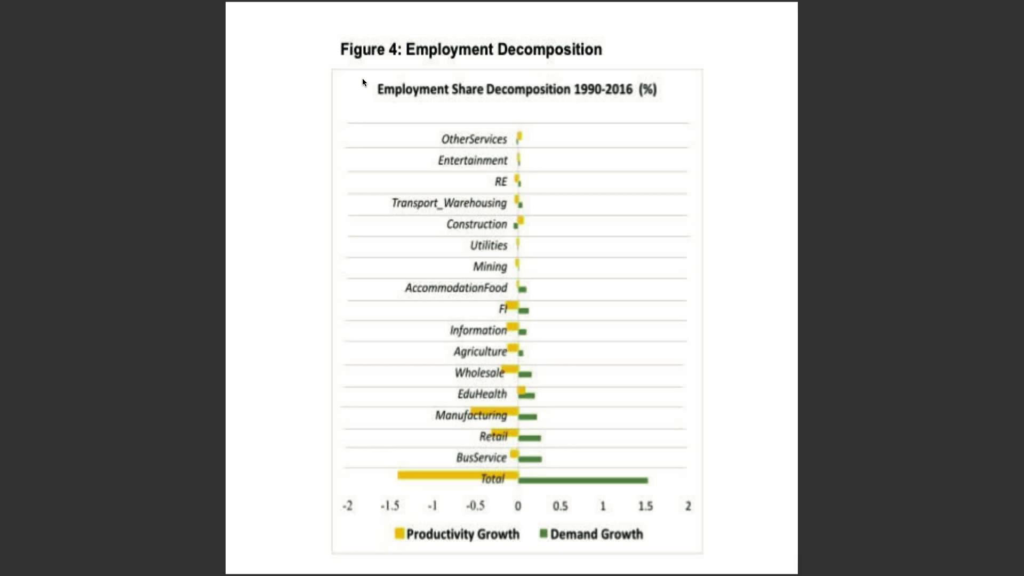

Now, this is obviously a big problem already. But there’s every reason to believe that the problem is actually getting worse. And one of the fascinating things I discovered when I started looking at the economic statistics is that if you look at jobs that actually are useful, and let’s again look at caregiving. Remember the big growth in jobs over the last thirty years has been in two areas, which are sort of collapsed in the term “service” but are really actually totally different. One is the sort of administrative, clerical, and supervisory work. And the other is the actual caregiving labor, the work where you’re actually helping people in some way. So, education and health are the two areas which show up on the statistics.

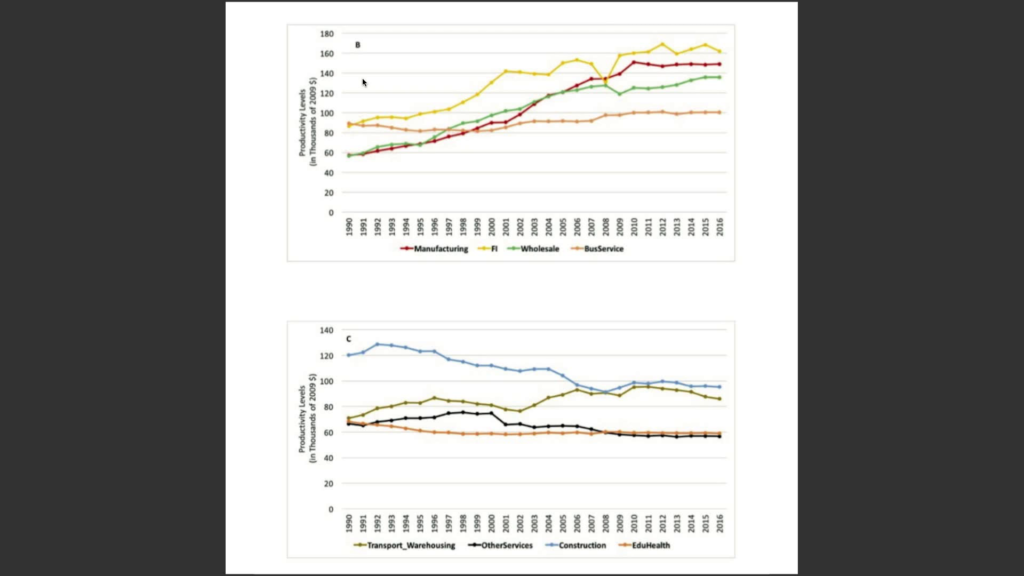

Okay, if you look at these statistics you discover that productivity in manufacturing as we all know is going way up. Productivity in certain other areas—wholesale, business services—are going up. However productivity in education, health, and other services—basically caregiving in general, insofar as it shows up on the charts, productivity’s actually going down.

Well why is that? That’s really interesting. We’ll talk in a moment about what productivity actually even means in this context. But here’s a suggestion as to why.

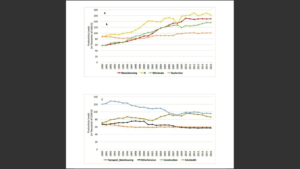

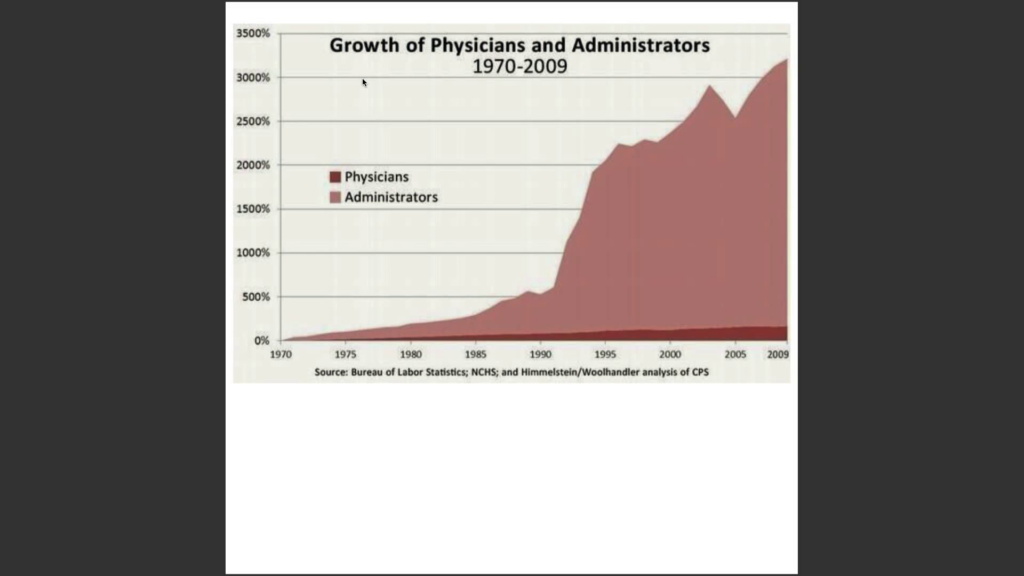

This is the growth of physicians on the bottom, versus the growth of actual medical administrators in the United States since 1970. It’s a fairly impressive-looking graph there. Basically, that sort of giant mountain there is what I called the bullshit sector. There’s absolutely no reason why you’d actually need that many people to administer doctors.

And actually, the real effect of having all those people is to make the doctors and the nurses less efficient rather than more. Because—I know this perfectly well from education, because I’m a professor; that’s what I do for a living. The amount of actual administrative paperwork you have to do actually increases with the number of administrators. Over the last thirty to forty years…you know, something similar has happened—it isn’t quite as bad as this. But something very similar has happened in America in universities, that the number of professors has doubled but the number of actual administrators has gone up by 240, 300%. So…hold on, more than that, actually. So, suddenly you have like twice as many administrators for professors as you had before.

Now, you would think that that would mean that professors have to do less administration because you have more administrators. Exactly the opposite is the case. More and more of your time is taken up by administration.

Well, why is that? The major reason is because the way it works is, if you are hired as you know, executive vice provost or assistant dean or something like that, some big shot administrative position at a British or American university, well you want to feel like an executive. And they give these guys these giant six-figure salaries. They treat them like they’re an executive. So if you’re an executive of course you have to have a minor army of flunkies, of assistants, to make yourself feel important.

The problem is they give these guys five or six assistants, but then they figure out what those five or six assistants are actually going to do. Which usually turns out to be…make up work for me, right. The professor. So suddenly I have to do time allocation studies. Suddenly I have to do…you know, learning outcome assessments, where I describe what the difference between the undergraduate and graduate section of the same course is going to be. Basically completely pointless stuff that nobody had to do thirty years ago and made no difference at all, to justify the existence of this kind of mountain of administrators and just give them something to do all day.

Now, the interesting result of that is that…and this is where this sort of stuff comes in. It’s actually…the numbers are there, but it’s very, very difficult to interpret. So I had to actually get an economist friend to sort of go through all this with me and confirm that what I thought was happening was actually happening. Essentially what’s going on is just as manufacturing, digitization is being employed to make it much more efficient. Productivity goes up, the number of workers go down. The number of payment that they…you know, the wages are actually going way up in manufacturing. But it doesn’t really make a dent in profits because there are so few workers.

So okay. That we kind of all know about. On the other hand, in the caring sector the exact opposite has happened. Digitization is being used as an excuse to make lower productivity so as to justify the existence of this army of administrators.

And if you think about it, you know, basically in order to translate a qualitative outcome into a form that a computer can even understand, that requires a large amount of human labor. That’s why I have to do the learning outcome studies and the time allocation stuff, right. But really, ultimately that’s to justify the existence of this giant army of administrators.

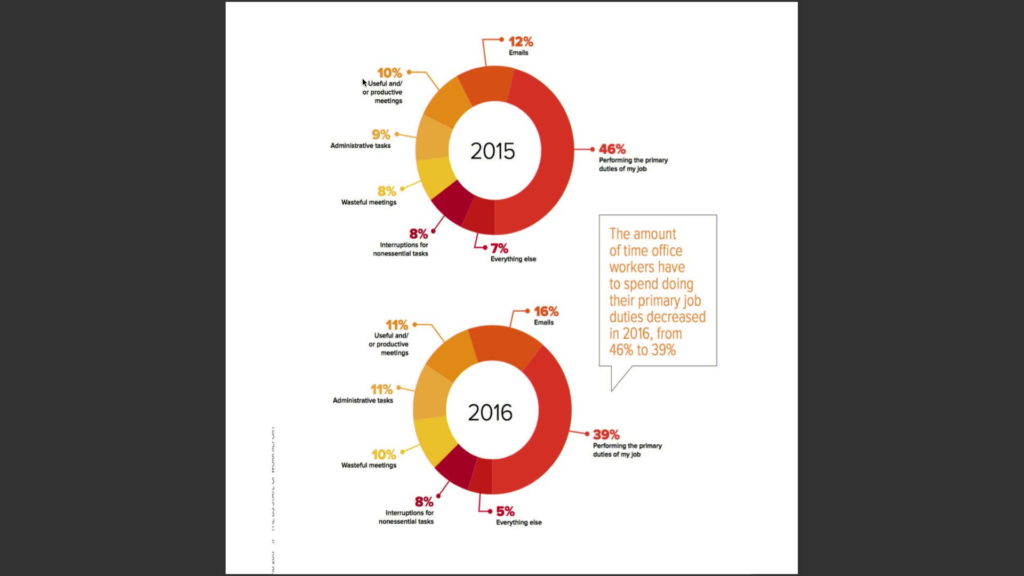

Now, as a result of that, you need to have actually more people working in those sectors to produce the same outcome, because they’re becoming less and less productive. More and more of your time has to be spent… Oh, yes. This is what the average company now looks like. More and more of your time ends up being spent sort of making the administrators happy and giving them an excuse for their existence.

This is a breakdown I saw in a report about American office workers, where they compared 2015 and 2016 and said you know, in 2015 only 46% of their time was spent actually doing their job. That declined by 7% in one year, to 39%. That’s got to be some kind of statistical anomaly. Because if that were actually true, in about a decade and a half, nobody will be doing any work at all. But it gives you an idea of what’s happening. So, if productivity is going down these people are just sort of working all the time to satisfy the administrators. So the creation of bullshit jobs essentially creates the bullshitization of real jobs. There’s both a squeeze on profits and wages. Because more and more money is going to pay the administrators. And you need to hire more and more people.

So what do you get? Well, if you look around the world, where is labor action happening? Basically, you have teachers strikes all over America. You have professor strikes in the UK. You have care home workers, I believe, in France. They had nursing home workers, first time ever on strike. Nurse’s strikes all over the world. Basically caregivers are at the sort of cutting edge of industrial action.

The problem, of course, and this is the problem for the left, is that the administrators who are the basic class enemy of the nurses—and I believe in New Zealand, the nurses wrote a very clear manifesto stating this. They said you know, the problem we have is that there’s all of these hospital administrators, these guys. Not only are they taking all the money so we haven’t got a raise in twenty years. They give us so much paperwork we can’t take care of our patients. So that is the sort of class enemy of what I call the caring classes.

The problem for the left is that often those guys are in the same union. And they’re certainly in the same political party. Tom Frank wrote a book called Listen, Liberal, where he documented what a lot of us had kind of had a sense of intuitively for some time. That what used to be left wing parties… Essentially the Clintonite Democrats, the Blairite Labor Party… You could talk about people like Macron, Trudeau. All of these guys, at essentially the head of parties that used to be parties based in labor unions and the working classes, and by extension the caring classes as I call them. But have shifted to essentially be the parties of the professional managerial classes. So essentially, they are the the representatives of that giant mountain of administrators. That is their core base.

I even caught a quote from Obama where he pretty much admitted it, where he said you know, “While people ask me why we don’t have a single payer health plan in America. Wouldn’t that be simpler? Wouldn’t that be more efficient?” And he said, “You know, well…yeah, I guess it would. But that’s kind of the problem. We have at the moment what is it two, three million people working for Kaiser, Blue Cross, Blue Shield, all these insurance companies. What are we going to do with those guys if we have an efficient system?”

So essentially he admitted that it is intentional policy to maintain the marketization of health in America because it’s less efficient and allows them to maintain a bunch of paper-pushers in offices doing completely unnecessary work, who are essentially the core base of the Democratic Party. I mean those guys. They don’t really care if they shut down auto plants, do they? In fact, they seem to take this glee. They say, “Well you know, economy’s changing, you just gotta deal with it.” But the moment those guys in the officers who’re doing nothing are threatened, the political parties leap into action and get all excited.

Alright. So, if you look at what happened in England, well it’s pretty clear that the conservatives won because they maneuvered the left into identifying itself with the professional managerial classes. There is a split between the sort of labor union base—which is increasingly unions representing very militant carers of one kind or another, and the professionals, managerials and the administrators, both of whom are supposedly represented by the same party.

Now, Brexit was a perfect issue to sort of make the bureaucrats and the administrators and the professionals into the class enemy. Now, it’s very ironic. Because of course, in the long run the people who’re really going to benefit from Brexit are precisely lawyers, right. Because they got to rewrite everything in England.

However, this is not how it was represented. It was represented your enemies— Well I mean, there was an appeal to racism, obviously. But there was also an appeal, your enemies are these distant bureaucrats who know nothing of your lives.

The key moment in terms—where essentially the Tories managed to outmaneuver Labor and guaranteed their victory was precisely by forcing Labor into an alliance with all the people like the Liberal Democrats and the other Remainers, who then used this incredibly complicated constitutional means to try to block Brexit from happening. And it was fun to watch at the time on TV. We were all transfixed. There were all these guys in wigs and strange people called Black Rod and you know…in odd costumes, appealing to all sorts of arcane rules from the 16th century. And it was great drama. You know, it was like costume drama come to life on television.

But in effect… And you know, it seemed like Boris Johnson was just being constantly humiliated. Everything he did didn’t work. His plans collapsed. He lost every vote he tried. But in fact, what it ended up doing was it forced what was actually a radical party which represented sort of angry youth in the UK into alliance with the professional managerials who live by rules, and whose entire idea of democracy is of a set of rules.

This is very clear in America. And again, you could see this in the battle of Trump versus Hillary Clinton. Clinton was essentially accused of being corrupt because she would do things like you know, get hundreds of thousands of dollars for speeches from investment firms like Goldman Sachs, who obviously aren’t paying politicians that kind of money unless they expect to get some kind of influence out of it. And constantly Clinton’s defenders would say, “Yes, but that was perfectly legal. Everything she did was legal. Why are people getting so upset? She didn’t break the law.”

And I think that if you want to understand class dynamics in a country like England or America today, that phrase almost kind of gives the game away. Because people of the professional managerial classes are probably the only people alive who think that if you make bribery legal, that makes it okay. It’s all about form against content. Democracy isn’t the popular will, democracy is a set of rules and regulations and if you follow the rules and regulations, well, you know, yeah that’s fine no matter… And these guys, that kind of mountain of administrators are the people who think that way. And they’ve become the base of parties— They are the electoral base of people like Clinton, people like Macron, people like Tony Blair hadn’t been. People like Obama.

And Corbyn was not at all like that. He’s this person who had been a complete rebel against his own party for his entire life. But what they did, was they maneuvered him into a position where there had been a Brexit vote which represented substance, the popular will. And he was forced into a situation where he had to like ally with the people who were trying to block it through legalistic regulation, essentially by appeal to endless arcane laws, thus identifying his class with the professional managerials.

And a lot of my friends who actually were out on doorsteps you know, they actually seem to think of Boris Johnson as a regular guy. I mean this guy, his actual name is Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson. He is an aristocrat going back like 500 years. But they seemed to think he was a regular guy, and Corbyn, who hadn’t even been to college was sort of a member of the elite, based almost entirely on that.

And if you look at people like Trump, and people like Johnson, how do they manage to pull off being populist in any sense? You know, they’re born to every conceivable type of privilege. Basically they do it by acting like the exact opposite of the annoying bureaucratic administrator who is your kind of enemy at work. That’s the game of images they’re playing. Johnson’s clearly totally fake. He fakes disorganization—he’s actually a very organized person according to people who actually know him. But he’s developed this persona of this guy’s all about content over form. And he’s just sort of chaotic and disorganized. So they basically play the role of being anti-bureaucrats and they maneuver the other side into being identified with administration, rules, and regulations, and those guys who basically drive you crazy.

The question for the left then is how to break with that. So I have what is it, fifteen minutes in order to propose how we can break with that? It strikes me that we need to kind of rip up the game and start over. We’re in another world economically than we used to be. And perhaps the best way to do it is to think about…well when people say their jobs are bullshit. You know, when that 37% of people who say, “If my job didn’t exist, probably the world would be better off. I’m not actually doing anything.” What do they actually mean by that?

In almost every case what they say is, “Well it doesn’t really benefit anyone.” There is a principle that ultimately work is meaningful if it helps people and improves other people’s lives. Thus, caring labor in a sense has become the paradigm for all forms of labor. And this is very very interesting because I think that to a large degree, the left is really stuck on a notion of production rather than caring. And and the reason we have been outmaneuvered in the past has been precisely because of that.

I could talk about how this happened. I think really a lot of economics is really theological; it’s the transposition of old religious ideas about creation, where human beings are sort of forced to… If you look at the story of Prometheus, the story of the Bible…you know, the human condition, our fallen state, is one where God is a creator, we tried to usurp his position, so God punishes us by saying, “Okay, you can create your own lives but it’s going to be miserable and painful.” So work is both is both productive, it’s creative. But at the same time, it’s also supposed to be suffering.

So we have an idea of work as productivity. So I was actually looking at these charts. They’re talking about the different productivity of different types of work. Now, I can see where the productivity of construction comes in. But according to this, you could even measure the productivity of real estate. The productivity of agriculture, okay. Productivity of… I mean, everything is production. What’s productivity of real estate, that doesn’t make any sense. You’re not producing anything—it’s land, it sits there.

Our paradigm for value is production. But if you think about it, most work is not productive. Most work is actually about maintaining things, it’s about care. Whenever I talk to a Marxist theorist, and they try to explain value, which is…what they always like to do, they always take the example of a teacup. They’ll say like…usually they’re sitting there with a glass, a bottle, a cup. They say, “Well, look at this bottle. You know, it takes a certain amount of socially-necessary labor time to produce this. Say it takes you know, this much time, this much resources.” They’re always talking about production of stuff.

But a teacup or a bottle, well you know, you produce a cup once. You wash it like ten thousand times. Most work isn’t actually about producing new things, it’s about maintaining things. We have a warped notion—which really…it’s a very gendered, right? Real work is like male craftsman banging away, or some factory worker making a car or something like that. It’s almost a paradigm for childbirth, right? Because labor is supposed to be…the word “labor” is very interesting, right? Because in the Bible they curse Adam to work and they curse Eve to have pain in childbirth. But that’s called “labor.” So there’s the idea that factories are like these black boxes where you’re kind of pushing stuff out like babies through a painful process that we don’t really understand. And that’s what work mainly consists of.

But actually that’s not what work mainly consists of. Most work actually consists of taking care of other people. So I think that what we need to do is we need to start over. We need to first of all think about the working classes not as producers, but as carers. The working classes are basically people who take care of other people. And always have been. Actually, psychological studies show this really well. That the poorer you are, the better you are at reading other people’s emotions and understanding what they’re feeling? That’s because, you know, it’s actually the job of people to take care of others. Rich people just don’t have to think about what other people are thinking or car—they don’t care, literally.

And so I think we need to A, redefine the working classes as caring classes. But second of all, we need to move away from a paradigm of production and consumption as being what an economy is about. Because if we’re going to save the planet, we really need to move away from productivism.

So I would propose that we just rip up the discipline of economics as it exists and start over. [applause] So this is my proposal in this regard. I think that we should take the ideas of production and consumption, throw them away, and substitute for them the idea of care and freedom. Think about it, you know. [applause] Thank you, yeah.

I mean, even if you’re making a bridge, right. You make a bridge becau—as feminists constantly point out—you know, you’re making a bridge because you care that people can get across the river. You make a car because you care that people can get around. So even like production is one subordinate type of care. What we do is, you know, as human beings, is we take care of each other.

But care is actually—and this is, I think, something that we don’t often recognize, closely related to the notion of freedom. Because normally care is defined as answering to other people’s needs. And certainly that is an important element in it. But you know, it’s not just that. Like if you’re in a prison, right. They take care of the needs of the prisoners. Usually, at least. To the point of giving them basic food, clothing, and medical care. But you can’t really think of a prison as caring for prisoners, right. Care is more than that. So why isn’t a prison a caregiving institution, whereas something else might be?

Well, if you think about care, what is the—kind of paradigm for a caring relation’s a mother and a child, right. A mother takes care of a child, or a parent takes care of a child, so that that child can grow and be healthy and flourish. That’s true. But in an immediate level, you take care of a child so the child can go and play. That’s what children actually do when you’re taking care of them. What is play? Play is like action done for its own sake. It’s in a way the very paradigm of freedom. Because action done for its own sake is what freedom really consists of. Play and freedom are ultimately the same thing.

So, a production/consumption paradigm for what an economy is is a guarantee for ultimately destroying the planet and each other. I mean, even when you talk about degrowth you know, if you’re working within that paradigm, you’re essentially doomed. We need to break away from that paradigm entirely. Care and freedom on the other hand are things you can increase as much as you like without damaging anything. So we need to think what are ways that we need to care for each other that will make each other more free? And who’re the people who are providing that care? And how can they be compensated themselves with greater freedom? And to do that we need to like, actually scrap almost all of the discipline of economics as it currently exists.

We’re actually just starting to think about this. Because economics as it currently exists is based on assumptions of human nature that we now know to be wrong. There have been actual empirical tests of the basic sort of fundamental assumptions of the maximizing individual that economic theory’s based on, and it turns out…you know, they’re not true. It tells you something about the role of economics that this has had almost no effect on economic teaching whatsoever. They don’t really care that it’s not true.

But one of the things that we have discovered, which is quite interesting, is that human beings have actually a psychological need to be cared for, but they have an even greater psychological need to care for others, or to care for something. If you don’t have that you basically fall apart. It’s why old people get dogs. We don’t just care for each other because we need to maintain each other’s lives and freedoms, but our own very psychological happiness is based on being able to care for something or someone.

So, what would happen to microeconomics if we started from that? We’re doing actually a workshop tomorrow on the Museum of Care, which we’re going to imagine in Rojava, which is in northeastern Syria where there is a women’s revolution going on, as you might have heard. But it’s in places like that where they’re trying to completely reimagine economics, the relation of freedom, aesthetics, and value. Because at the moment, the system of value that we have is set up in such a way that this kind of trap that I’ve described, and the gradual bullshitization of employment…where essentially production work has become a value unto itself in such a way that we’re literally destroying the planet. And in order to actually reimagine a type of economics that wouldn’t destroy the planet, we have to start all over again. So I’m going to end on that note. [applause]

Herald: David, thank you so much. I think it’s very interesting to also have some political views now that we mix in all sorts of technology, and it goes very good in the theme of Congress.

Please, if anyone has any questions line up by the microphones and we’ll go for that. Unfortunately in the beginning I forgot to mention that you can ask questions over the Internet through IRC, Mastodon, or Twitter. And remember to use the channel #borg, and we’ll make sure that they get answered. So please, microphone number one.

Audience 1: When you observe the productivity in healthcare going down, do you have an explanation according to neoliberal thinking why hospitals—one with more administrators, one with less administrators—don’t have a competition outcome that the hospital with less administrators wins?

David Graeber: [laughs] Yeah… Well, one of the fascinating things about the whole phenomena of bullshitization and bullshit jobs is that it’s exactly what’s not supposed to happen under a competitive system. But it’s happened across the board, equally in private sector and public sector.

Audience 1: Why?

Graeber Um…that’s a long story. But one reason seems to be that…and this is why I actually had managerial feudalism in the title, is that the system we have…alright—is essentially not capitalism as it is ordinarily described. The idea that you have a series of small competing firms is basically a fantasy. I mean you know, it’s true of restaurants or something like that. But it’s not true of these large institutions. And it’s not clear that it really could be true of those large institutions. They just don’t operate on that basis.

Essentially, increasingly profits aren’t coming from either manufacturing or from commerce, but rather from redistribution of resources and rent; rent extraction. And when you have a rent extraction system, it much more resembles feudalism than capitalism as normally described. You want to distribute— You know, if you’re taking a large amount of money and redistributing it, well you want to soak up as much of that as possible in the course of doing so. And that seems to be the way the economy increasingly works. I mean, if you look at anything from Hollywood to the healthcare industry, you know, what you’ve seen over the last thirty years is a creation of endless intermediary roles which sort of grab a piece of the pie as it’s being distributed downwards.

I mean I could go into the whole mechanisms, but essentially, the political and the economic have become so intertwined that you can no longer make a distinction between the two. So you have a prob— And this is where you go back to that whole thing about the 1% and using political power to accumulate more wealth, using your wealth to create more political power. You have an engine of extraction whereby the spoils are increasingly distributed. We get these very very large bureaucratic organizations, and that’s essentially how our economy works.

Herald: Great. thank you—

Graeber: I mean I could talk for an hour about the dynamics, but that’s basically it. You know, you could call it capitalism if you like, but it doesn’t in any way resemble capitalism the way that people like to imagine capitalism would work.

Herald: Great. Awesome. Questions from the Internet, please.

Audience 2 [Angel?]: How to best address this caregiver class, when the context of the proletariat is no longer given to awake their class consciousness?

Graeber How to address the caregiver when the proletariat is no longer what?

Herald: Please repeat the question.

Audience 2: How to best address the caregiver class when the context of the proletariat is no longer given to awake their class consciousness?

Graeber Given to awake?

Audience 2: I’m not sure what they’re asking about.

Graeber: Yeah. I mean the question is how do you create a class consciousness for that class? Yeah, yeah. Well, that is the question. I mean, first of all you need to actually think about who your actual class enemy is. And I mean, I don’t mean to be too blunt about it, but I mean the problem we have, why is it people are suspicious of the left? And people like Michael Albert were pointing this out years ago, that one reason that actual proletarians were very suspicious of traditional socialists in many cases is because their immediate enemy isn’t actually you know, the capitalist who he rarely meets, but the annoying administrator upstairs. And you know, to a large extent, traditional socialism means giving that guy more power rather than less.

So I think we need to actually look at what’s really going on in a hospital, in a school. And you know, I use hospitals and schools as examples, but they’re actually very important ones, because people have shown that in most cities in America now, hospitals and schools are the two largest employers. Universities and hospitals. Essentially work has been reorganized around working on the bodies and minds of other people rather than producing objects. And the class relations in those institutions are not…you can’t use traditional Marxist analysis. You need to actually reimagine what it would mean. Are we talking about the production of people? If so, what are the class dynamics involved in that? Is production the term at all? Probably not. Why not?

That’s why I say we need to reconstitute the language in which we’re using to describe this, because we’re essentially using 19th century terminology to discuss 21st century problems. And both sides are doing that. The right wing is using like, neoclassical economics, which is basically Victorian. It’s trying to solve problems that no longer exist. But the left is using a 19th century Marxist critique of that, which also doesn’t apply. We just need new terms.

Herald: Thank you, I hope that answered the question from the Internet. Microphone number two, please.

Audience 3: So, the question is basically to what extent can technology help? And the subtext here is there’s actually really lots of projects now whose function at some level is to automate management.And to the extent to which that can be molded into removing this class that you’re talking about, or somehow making it too painful for them to exist. Some of these projects are companies but some of them are very independent things that have very sophomoric ideas but with tens of millions in funding.

Graeber: Yeah. Well that’s the interesting thing, that people talk about it all the time. But this is where power comes in, right? I mean why is it that automation means that if I’m working for UPS, the delivery guy gets like Taylorized, and downsized, and super-efficient to the point where our life becomes a living hell, basically. But somehow the profits that come from that end up hiring like, dozens of flunkies who sit around in offices doing nothing all day.

One of the guys when I started gathering testimonies—I gathered several hundred testimonies of people with bullshit jobs or people who thought of themselves as having bullshit jobs. And one of the most telling was a guy who was an efficiency expert in a bank. And he estimated that 80% of people who worked in banks are unnecessary; either they do nothing or they could easily be automated away. And what he said was that it was his job to figure that out. But then he gradually realized that he had a bullshit job because every single time he proposed a plan to get rid of them…they’d be shot down. He’d never got a single one through. And the reason why is because if you’re an executive in a large corporation, your prestige and power is directly proportional to how many people you have working under you. So no way are they going to get rid of flunkies. I mean, that’s just gonna mean the better they are at it, the less important they’ll become in the operation. So somebody always blocked it.

So this is a basic power question. You can come up with great technological ideas for eliminating people; people do all the time. But you know, who actually gets eliminated and who doesn’t has everything to do with power.

Herald: Great. Thank you. And last question, please, from microphone number five.

Audience 4: Can we maybe have one question from a non-male person?

Graeber: Yeah. That’d be nice.

Herald: Non-male person.

Audience 4: Oh no, now that person’s just left. Do you want to—

Herald: Sorry, I am not choosing questions based on stuff. We’re kinda choosing all around the hall.

Audience 4: Okay, have [fun?].

Herald: Please, microphone number five.

Audience 5: Thank you for the opportunity to speak. I heard that you… I really like your description of a paradigm, or that people are stuck on production and consumption, and that you would like to change the paradigm to a paradigm towards more care and freedom, etc. And for me it kind of sounds a little vague. And that’s why I myself think of basic income as a human right, as the actual mean to break with the current hegemonic, macroeconomic paradigm, so to speak. And I was interested in your… [crosstalk] …point of view on that, basic income.

Graeber: My view of that. Ah. Yeah. Well I actually totally support that. I think that one of the major objections that people have to universal basic income is essentially people don’t trust people to come up with useful things to do with themselves. Either they think they’ll be lazy, right, and won’t do anything. Or they think if they do do something it’ll be stupid. So we’re going to have millions of people who’re trying to create perpetual motion devices or becoming annoying street mimes or bad musicians or bad poets, or so forth and so on.

And I think it actually masks an incredible condescending elitism that a lot of people have, which is really the mindset of the professional managerial classes who think that they should be controlling people. Because okay, if you think about the fact that huge percentages, perhaps a third of people, already think that they’re doing nothing all day and they’re really miserable about it, I think that demonstrates quite clearly why that isn’t true.

First of all, the idea that people if given a basic income won’t work. Actually, there are lots of people who are paid basically to sit there all day and do nothing, and they’re really unhappy. They’d much rather be working.

Second of all, if 30 to 40% of people already think that their jobs are completely pointless and useless, I mean, how bad could it be? It’s like you know, even if everybody goes off and becomes bad poets, well at least they’ll be a lot happier than they are now. And second of all, one or two of them might really be good poets. If just .001% of all the people on basic income who decide to become poets or musicians or invent crazy devices actually do become Miles Davis or Shakespeare, or actually do invent a perpetual motion device, well you know, you’ve got your money back right there, right?

Herald: Great. Thank you so much. Unfortunately that was all the questions that we had time to. If you have any more questions, please, I’m sure that David will just take a few minutes to answer them if you come up here.

Graeber: Oh yeah. I could spend the rest of my life doing this.

Herald: Thank you so much David Graeber for your talk. And please give him a great round of applause.

Citations

- Lean on Me: A Politics of Radical Care

- Over Work: Transforming the daily grind in the quest for a better life

- La valeur du travail selon l’entraide anarchiste et le care éthique : une critique radicale du capitalisme managérial

- The sacrificed lives of the caring class: crises of social reproduction, unequal Europe, and modern forms of slavery

- Reflections on modern physical activity: how can Graeber’s ideas help us to reconceptualise it and increase the value of play?

- What has changed? Care home work during the pandemic in Jack Thornes’ Help: No one is coming

- A művészet eltagadott gazdaságának feminista megközelítése [A Feminist Approach to the Disavowed Economy of Art]

- Curating with Care

- Urgent Business: Five Myths Business Needs to Overcome to Save Itself and the Planet

- The Pandemic State of Care: Care Familialism and Care Nationalism in the COVID-19-Crisis; The Case of Germany

- Art Work: Invisible Labour and the Legacy of Yugoslav Socialism

- Care and caring: (by) force or (by) fiction

- Space, Supplies, Solidarity in an Intensive Treatment Unit during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Interview with Efie Galiatsou, ITU Doctor in a London Hospital