Mark Surman: So, good morning. I guess good afternoon, re:publica. Great to be back. So I was here last year, and last year what I talked about was really the rise of digital empires. And in particular that both companies and governments are using the Internet to consolidate power in ways that we really have never seen before.

And I talked about taking inspiration from the environmental movement and building a movement for the health of the Internet—something to balance those empires. And that that movement really needs to be something not just about protesting, although demanding what we want from governments is a part of that. It also needs to be about actually coding, building, and figuring out the digital future we want.

And in that I did talk about one goal, which we’ve been working on and we have an event upstairs in the laboratory here about, making the health of the Internet, just like the health of the planet, a mainstream social issue.

So Mozilla and many many of you have still been working on that in the last year. What I want to do this year is get to some of the more specific issues. If we need to build a movement for the health of the Internet, if we want to stand up for an Internet that reflects all of us, what are the things we need to be talking about now?

And I pondered for a while and I thought maybe I’ll talk about the rise of authoritarian governments and how they’re playing into taking advantage of the Internet and eroding the Internet, and I decided not to talk about that. Instead I decided to talk about pets.

And they’re actually all connected and I’ll come back to the connection at the end. But really where I want to go now is something very specific but also very huge, which is these are Bluetooth teddy bears and unicorns, and actually earlier this year it came out that the technology behind them was very very easily hacked—super insecure. And millions of recordings of children talking to their parents through the video cameras in those toys, and millions of recordings of the parents talking to their children, were easily accessible from Amazon if you knew the right way to get access to them.

And I want to talk about those not just as a security story or a story about teddy bears, but really in the context of what we’ve talked about as the Internet of Things and what it means for the health of the Internet and basically I think for for the structures of power and the structures of human interaction in our society.

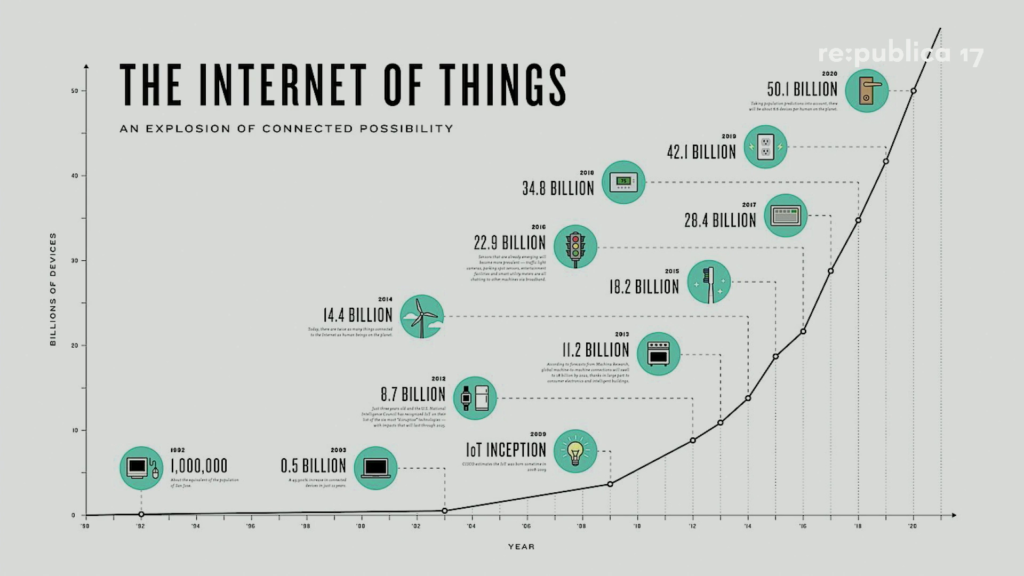

And you know, you can use whatever term you want. Internet of Things is the easy one to use because it’s been picked up by business and by the media. The important point about it and why it’s worth us all really beginning a dialogue around this right now is that between now and—you can see it kind of going up—the Internet of Things is any kind of connected device, will be at 50 billion devices in just three years.

And so that means almost ten devices for every person on the planet—not quite but almost that. And that’s just three years from now. So we’re talking about everything from teddy bears, to our cars, to our appliances, to our cities, having an Internet and sensors and cameras and microphones built into them. And we really are talking about an era of completely pervasive computing, a computer that spans the whole globe and envelops all of us.

And on top of that, there are three other trends that are connected into that which are also moving at an extreme pace. One is the emergence of widespread voice interfaces like Amazon Alexa. The other is VR starting to become a reality. And the third is artificial intelligence and machine learning, which are becoming very very real, much faster certainly than I expected, as really it’s just about a set of algorithms taking the big data, the training data that we all generate every single day as we use every single app.

So at this stage in the evolution of that, it feels like to me and and a number of other people who I know here in the audience who I work with, this is a moment to ask as we make the planet digital, as we totally envelop ourselves in the computing environment that we’ve been building for the last hundred years, what kind of digital planet do we want? Because we are at a point where there is no turning back, and getting to ethical decisions, values decisions, decisions about democracy, is not something we have talked about enough nor in a way that has had impact. And now with that meteoric growth of computing all around us, it feels essential that we have that conversation now.

And sticking with the environmental metaphor, we really are at a choice point where we could build a forest, a rich ecosystem, something that supports life. Or we could end up very quickly with a clearcut, where there’s not much of anywhere to live and not much around at all.

So what I want to do is just take us through three things. Some of the things that are hopeful to me and that we’re building a healthy ecosystem, a forest, that we all can get involved in or people here are involved in. And then I want to talk about the more negative scenario as well as some things we can do.

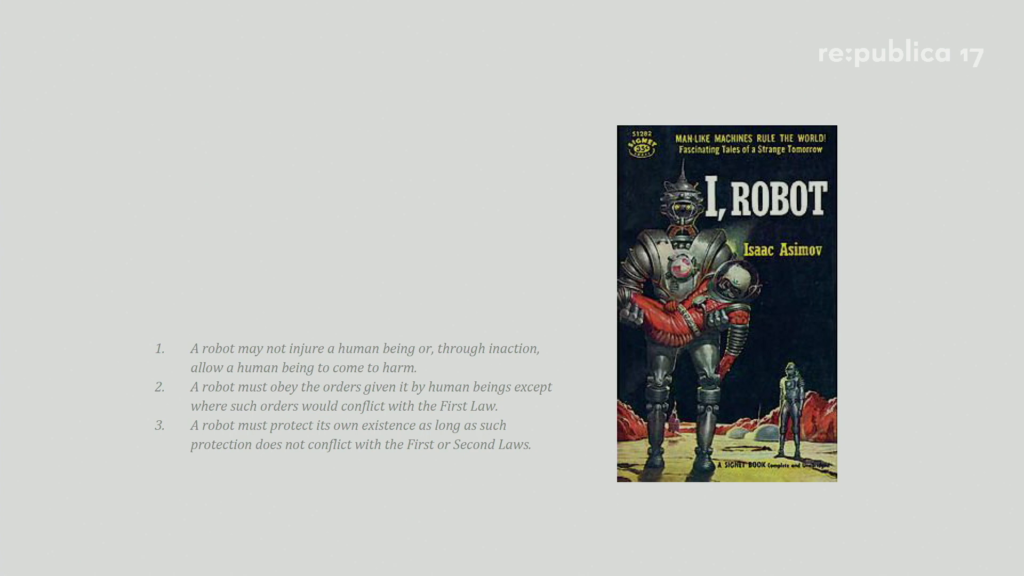

And I’m going to start out with a piece of science fiction, I, Robot from Isaac Asimov. Not just because the world is about to be flooded with robots—which it is. But because this is where Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics first show up. And the Laws themselves are not important. What is important is that in this Asimov posits, as we rarely do right now, that we can consciously talk about the rules we want to operate with in relationship to machines. And now we’re in the moment where we need to be having that conversation, for real, at a global scale, in a way with real political power behind it the has influence. We have to be talking about the kind of world we want.

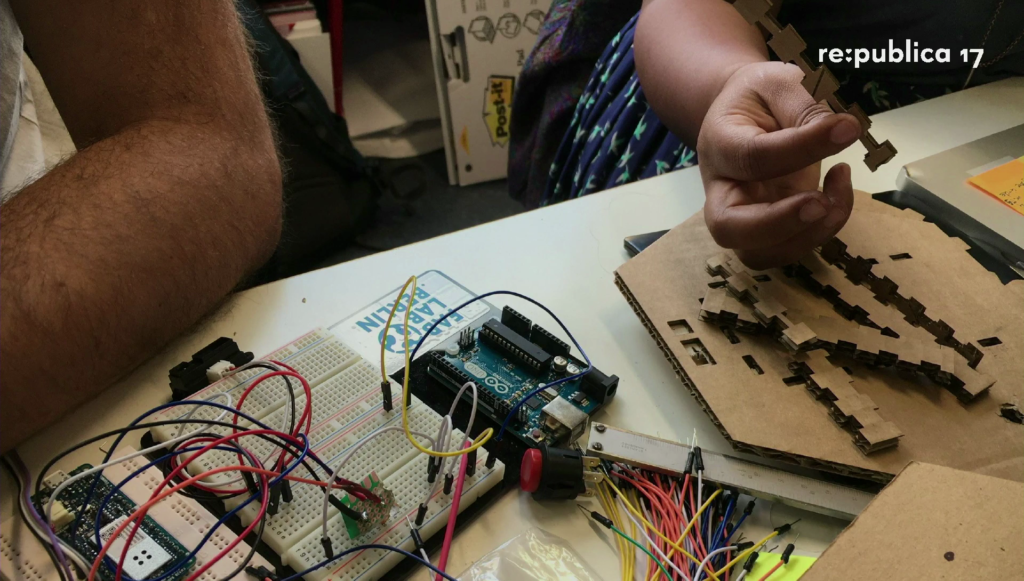

And I have some hope in that when I look around at the open hardware movement— (And this is a set of people in a workshop that Mozilla’s Open IoT studio was running, building some things with Arduino) —in that I grew up at a time certainly surrounded by computers, and I think most people in the smartphone world live in a time today where hardware, the material of the Internet of Things, seems immutable. It comes from a factory. And the open hardware movement really in the last ten years has grown up and said no, it doesn’t have to be that way. The same principles we applied to open source can be true of all of the computing around us.

Now, that still seems crazy. This is a hobbyist thing. But people are doing fun and interesting things as well as learning and painting a different future. They’re building a fingerprint scanner—a garage door opener—that is not connected to Apple’s cloud or Google cloud or Amazon’s cloud. They’re chasing away raccoons with their own motion-detecting squirt gun robot, which is also not connected to the Amazon cloud or the Google cloud or the Apple cloud. They’re keeping themselves safe by building a jacket that says which way I’m turning on my bicycle.

Maybe a little more frivolous, possibly stupid, they’re building self-lacing Nikes with Arduinos. And my favorite as I looked around for things people are building with Arduino today, a smartphone-controlled pumpkin flamethrower. Everybody should have one. Keeps the kids you don’t like away at Halloween.

So these are real things people are doing and they show some whimsy, some pragmatism, but also that we are at a spot where the hardware around this is something we could play with.

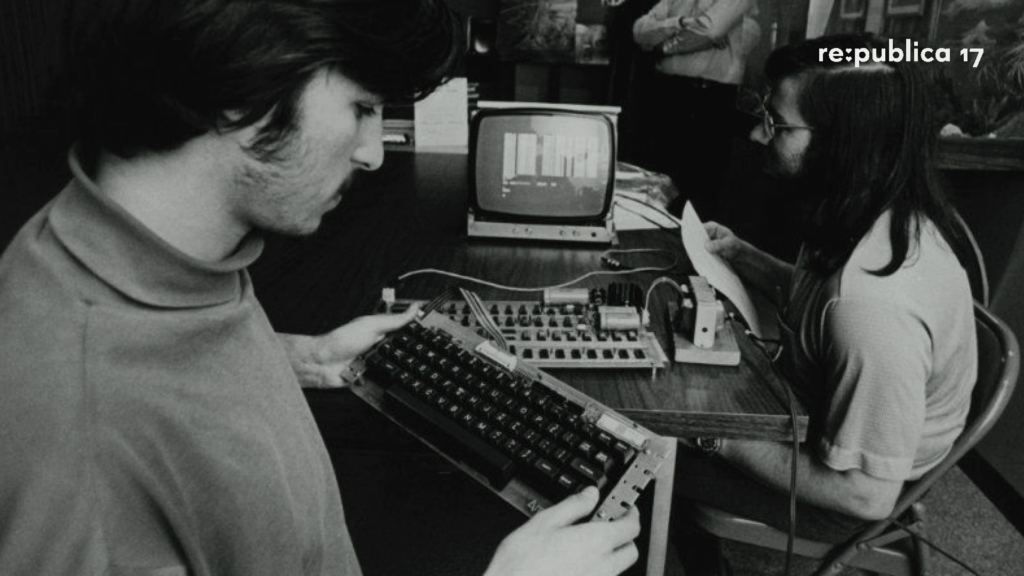

Now, Unfortunately— And there’s all kinds of ways we could give a whole talk just digging into that, I think where we are now with open hardware still is stuck at the place that say the Homebrew Computer Club (which which this is a pixelated photo of) was in the 70s. And of course the Apple computers come out of that. So it’s good, it’s a bunch of people playing with technology. And some of the values of that hacker ethic that are there in the early phases of this kind of work stay through even to today. But certainly in early computing, general purpose computing, is something that invites all of us to do what we want with a computer, which is very different than many previous technologies.

But, that also led to the centralization, the consolidation of power… To think that those people who built the Apple I also are building some of the biggest power consolidation systems in the world. It didn’t go exactly in the direction and on the values that we hoped.

So just to think about IoT for a second, how do we get to the future we want? And a place that I take inspiration from and and a bunch of Mozilla people are involved in, is a set of things of which this Good Home Project here is one, where people are looking at design and ethics and the human outcomes we want as things that we can actually dig into and direct in terms of where we’re going in the world of pervasive computing.

So The Good Home is a series of kind of roving exhibits and a set of people who are working on those sorts of questions. And the kinds of things that they do— These are all off the web site so I don’t know if they’re from the London or the Milan or both exhibits they did. But Internet Adhesives, something by Michelle Thorne (who’s here today up in the Internet health clinic from Mozilla) positing that really we shouldn’t have to take these manufactured devices from factories and buy things new all the time. But we should be able take pieces of technology and weave them into things in our everyday lives and make them do what we want in whimsical and also pragmatic ways.

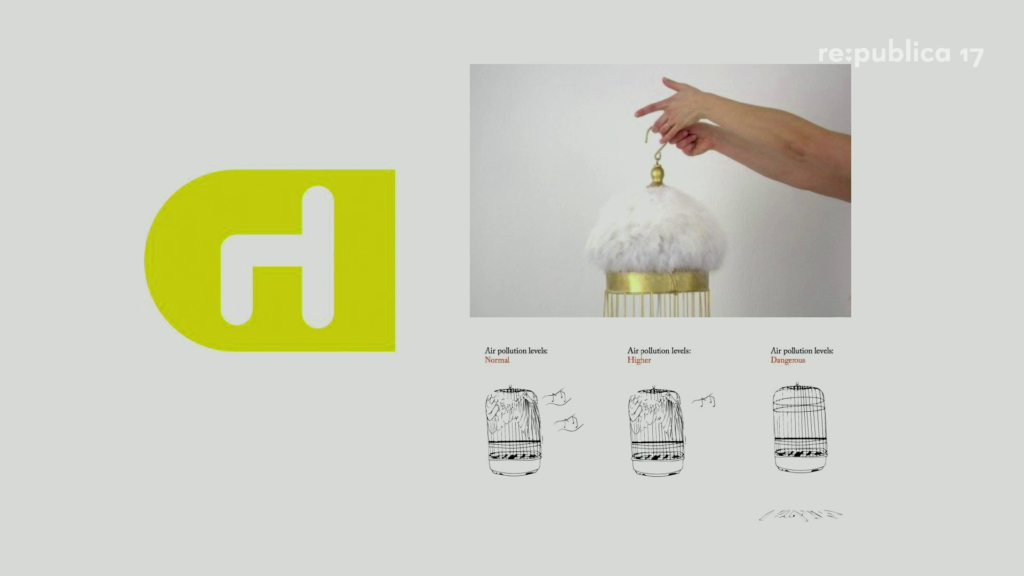

The very fun birdcage concept which was on display of an Arduino or kind of an open hardware-driven piece of art that actually also tells me about air quality, much like a canary in a coal mine would.

And then one of my favorites, the Privacy Dimmer, which is really a kind of ecosystem of open hardware as well as beautiful objects aimed at being able to configure how we want privacy to work in our home and with our data in ways where there are presets on the smartphone as well as then beautiful devices that are much more natural in the flow of our life, where we express what we want our privacy to be at any particular moment.

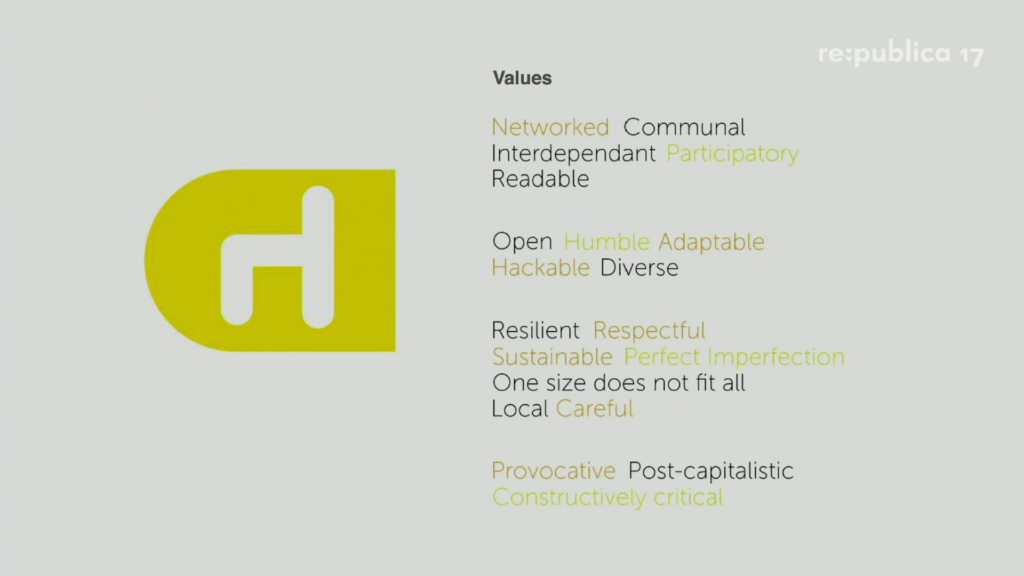

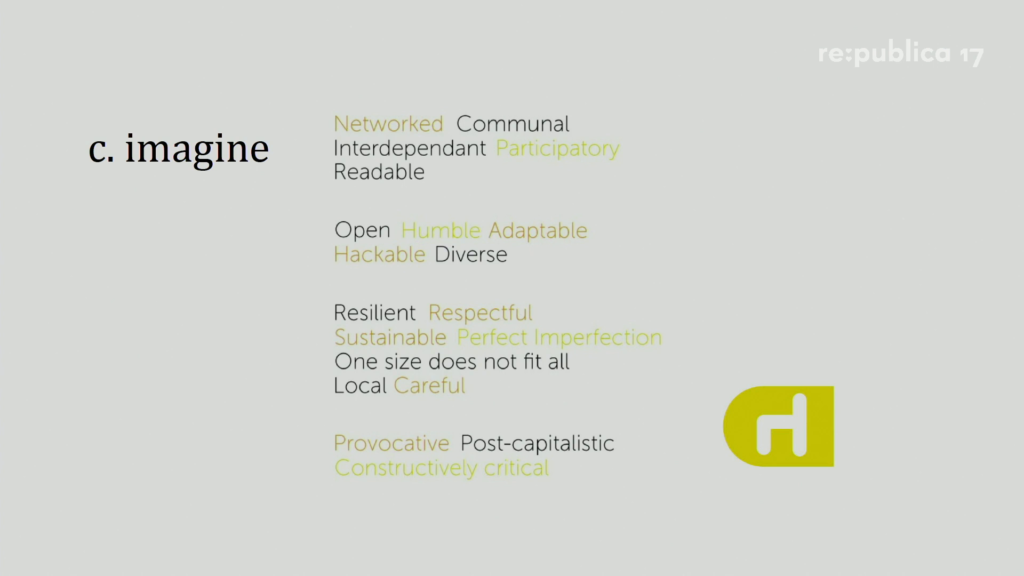

And the values of this Good Home Project to me are what is exciting, and also frankly what I think really points to the fact that this next era, if we engage it properly, could be more shaped by Europe and other parts of the world and not by America, which is very much where this is coming from. Looking at being open, being humble, being resilient, being local, being sustainable, being post-capitalistic (which is not being anti-capitalistic), understanding there is an economy around this, but it should be a human economy.

And the idea that we explore with this to me is another level up beyond the Homebrew Computer Club, beyond just working with open hardware. It’s saying, “We can design this future. It is a critical moment. And if we don’t, it’s gonna go another way.” And I’ll get to that in a second.

And the good news also out of Europe is that you have other people doing the same thing. The IoT Design Manifesto has a similar set of values, a similar set of propositions, although targeted a little bit more at developers. And all of those things really go back to that same idea of the Three Laws of Robotics. We can make a bargain, make a plan, set rules, have values, that say where we want to go with this society.

So if we push ourselves in the right direction we can have a rich ecosystem. We can have a forest. Or we can decide to cut it down. And I worry that very quickly that is where we’re headed, is in to the clearcut of the digital planet and all of us.

And just take a moment with another piece of science fiction just quickly. This is Philip K. Dick’s Ubik. He’s probably my favorite science fiction author. And I don’t put this here for the obvious reason, but the obvious reason is this weird force called Ubik shows up at the first chapter of every chapter in that book as a different product. Much like the Internet, and power, and Google do always show up as a different product but are really one thing.

The reason I want to bring this is much more about the banality. And you don’t need to read the screen, I’ll read it for you. There’s a great passage in the book where the door refused to open, and it says, “Five cents, please.”

And then the main character searches his pockets, he doesn’t any coins. He says, “I’ll pay you tomorrow.” The door is still locked. “What I pay you,” he says to the door, “is in the nature of a gratuity; I don’t have to pay you.”

And the door says, “I think otherwise. Look at the purchase contract you signed when you bought this apartment.” He found the contract and sure enough, “payment for his door opening and shutting constituted a mandatory fee. Not a tip.” It’s kind of funny and banal, but that’s fifty years ago and frankly it is the world that we are making and designing.

So just some funny but also worrisome examples. This is a piece highlighted in Boing Boing of a product called Juicero. (It’s an awesome name; only could you find products named so well on the program Silicon Valley.) But this is a juicer that won’t work unless you buy their packages of kale juice or carrot juice or whatever. And if they’re older than six days old, based on the bar code, they won’t even let you use the packages they sold. Very much like the door. But now, funny. If you buy it you’re probably stupid. I’m sorry if anybody here is a Juicero owner. But you know, it is a kind of thing that is happening.

And then of course the story about the teddy bears. And the similar story about the sex toys, where there’s actually a class action suit for the amount of personal data they collect on your use of the sex toy, which they’ve since offered to pay people who did disclose their data and stop collecting that data.

All point to that this world of the Internet of Things and all of the data collection, all of the AI around it, is really getting into the most intimate parts of our lives. We should have a say, we should be thinking about, we should be talking about, how we want that to work, and not just accepting that it works a certain way and is too complex.

And of course as we look at this growth of computing devices, the Internet of Things, there is even more to talk than just how it kind of comes into our intimate lives. If you remember from last year, this botnet named Mirai, which has been used many times since, took over a bunch of Internet of Things devices— Which because because they tend to be sort of off to the side of our lives, they’re not our computers that we update, or our phones that we update so frequently, are easy targets for these botnets, that can then be used for Denial of Service attacks. And the Mirai botnet took down Twitter and dozens of other sites by a Denial of Service attack at a scale that has been rarely seen. And the piece about that is we are just at the tip of the iceberg of the security threats—not just botnets—that we are creating by creating a pervasive computing environment where there are no regulations, no requirements, around security.

And Bruce Schneier, who’s at MIT, talks about it and a number of other people do as well, that kind of privacy pollution as being like an environmental externality. The people who produce those devices often, far from the places where the damage happens, have no incentive and in most cases don’t give a damn whether they are creating something that can create tremendous economic and social havoc. And we actually have to be serious about that we are dramatically accelerating a threat to ourselves because we have wound computers around us into our lives and our economy, and thought nothing of how their vulnerability can take us out in the kneecaps and damage us in real ways.

And then of course the other and obvious piece which is rarely talked about, is starting to get talked about more, not talked about enough, really is that as we get to AI and connected devices together, the job situation will totally change. You know, we talk about 40, 50 percent unemployment in industrialized societies or post-industrialized societies as being a real thing in the next ten, twenty, thirty years. And that is very much tied to that spike of the Internet of Things. It’s not just about getting a connected toaster.

And so whether that is Uber, which is controversial for many of other reasons, being on the forefront of that, its drivers will all be fired at some point. Or many other kinds of automation. The connected device/AI world will fundamentally change the fabric of work and our economy, soon, and we’re not talking about it enough.

Rise of the AI fashion police, The Verge

And then the more obvious one but you can’t ignore it because it is so pervasive, is the listening machine that we are building all around us. And this last couple weeks, I guess last week even, Amazon Alexa went to another level. They released the Echo Look, which you can see here, which is the incredibly helpful camera and microphone you can put in your bedroom so they can give you fashion advice and sell you clothes if you’ve run out of socks or your clothes don’t match. The AI can help you with that.

But of course really what we are doing is putting microphones and cameras all around us in ways that Orwell never could have imagined, and that we’re buying out of delight and excitement and our own money.

And of course it’s not just the companies who are watching that. Those IoT devices are easy targets for state actors or non-state actors who have malicious intent. So we are building a panopticon never imaginable, out of the consumer devices that we all so desire, and it is growing by leaps and bounds in its scale and interconnectivity.

And so that’s really the thing to sit in as we kind of come to a close but then also maybe look at action, is the scale of this really— I don’t think any of us even when we’re talking about it have imagined. And if we bring the wrong values into wrapping computers all around us, we have many many things that can go wrong, and certainly we can imagine a digital world—which is the world at this point—that is very much like a clearcut. And I’m worried that that’s where we’re headed.

So the question, especially at a place like re:publica for people who are politicized about these things, is what does stewardship look like? So to stick with the environmental metaphor, what does it look like in this world for us to steward the values that came with the Internet or that we bring as people who want human society to be good and kind and ethical and inclusive and multicultural and global? What kind of digital planet do we want is a thing we need to ask in a very serious way, not just as cocktail party conversation, as that grows.

And so I do think the forest is possible. The clearcut is avoidable. We can create a responsible, ethical, and human digital planet. But we have to take it seriously as a mainstream political issue, as a mainstream thing that we build right now. And there’s three things as we try to grow that moment that I think we all need to be doing more of and putting more money behind that are very much in the tradition of environmental stewardship and build on the last ten, twenty, thirty, forty, fifty years of hackers and digital making as a form of stewardship. Just standing in the streets alone will not get us the responsible, ethical, human digital planet we want.

So what do we need to do? Certainly one thing is build it. Just build it now. And that’s hard. This is Casa Jasmina, which is an open source connected home in Turin in Italy, started by Bruce Sterling the science fiction author and others. And why I use it as an example of “build it” is we can and must build an ethical, responsible digital world that reflects our values in a way that reflects design and is real and that we use every day.

Just motion-controlled raccoon squirt guns will not change things. We need to see how do we actually make open source, secure, human-controlled, people-controlled, not centralized, not monopolized, digital lives possible. I mean, you could also just check out and go and live in a forest, but even that forest is completely connected into this world more and more. So we have to in a serious way that involves design and technology and politics, look at building real worlds that reflects the kind of values I talked about earlier in the Good Home piece.

Consumer Reports, November 2016 cover

We need to organize, but not necessarily just in the street and in ways that traditional movements have. And why I put this up here, although this is an American example, is that Consumer Reports (and there are similar organizations around the world, consumers unions) has really started to look at privacy as the main consumer issue in the next decade to organize around.

And one of things it’s done, what that symbol is there on the side, is start to build a privacy testing standard, knowing that it is going to need to engage a network of other organizations and citizens to privacy test the scale of products that we have in front of us, and to point to companies that need to improve their privacy and security standards. Because they can’t— You know, in their history of testing washing machines and cars, they could do it all themselves. They can’t do that themselves.

So we need to think of ways to organize collectively as people, as citizens, as consumers, that really tackle and hold companies and governments to account and also and bring our own solutions, our own teaching, our own ways of doing things, into a movement of a scale that is as big or bigger than the environmental movement ever was.

And then the last thing I would just say is we do need to imagine. We need to imagine a world where these kinds of values about resilience, sustainability, human-centered design, human-centered life where people and not machines are in control. That we need to imagine that in a real way. It can’t just be a light conversation.

And what I like about the [Good] Home project, Casa Jasmina, many things like that—which again Europe has an edge on—is it is people getting involved in trying to build with those values as well as have conversations on those values. And it cannot be underestimated that if we do not do that now, we don’t treat that as the most urgent or one of the most urgent political acts we can do to engage in what those values should be, to build and to organize around them, we are going to be fucked. We’re probably already fucked. But we’re certainly fucked if we don’t do that.

And that brings me to the end, which is this does actually connect to the rise of authoritarian governments, whether that is here in Europe, or in the Middle East, or Russia, of in the US. And you know, the world— All of us have been talking about this a lot right now. The world that we live in, or at least that I live in and I value, that is a global world that is connected. Where we can move freely by and large. Where ideas and money can move freely by and large. Where we really actually do see multiculturalism as a part of what is an essential fabric of the global world because you can’t have a global society without it.

Those are things that I kinda for granted as values. If you go back and read John Perry Barlow’s “Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace,” he talks about those things as being values for the digital world we’re building. I take those for granted as a part of the politics of the Internet. And we also have built a global economy on the Internet that has… You know, we can split hairs and fight each other but has a lot of those values built in, which if you compare to the rest of history beyond the last fifty, eighty years, are not the values by and large that humanity has had.

We have lived in divided societies. We have lived in worlds divided by nations. We have lived in a world of war. (Although we still do.) And the politics around us is taking us back there. So it really—when we think about the politics of the Internet, which are actually very much as we’ve seen in recent elections, interwoven into what is happening with the politics of the state, there is no more urgent time than ever if we want a society that is inclusive, that is global, that is multicultural, and where we shape the future, to also get involved in the politics of the Internet and bring into the mainstream the idea that we need a healthy Internet that we control. The stakes have never been higher, and this is the kind of group that needs to get involved and really grow something big. Thank you very much.

Further Reference

Session description at the re:publica site