Peggy Deamer: Hi. I too really want to thank Damian for this invitation, and it’s an honor to be included in this fabulous group and this amazing discussion. I feel like I learned much more than I than I give. So I look forward to this day.

So just to say, the work that I’m doing is very much part of the work of The Architecture Lobby, for which I am the research coordinator. And so I want to acknowledge very much their work. Some of the things I’m going to say don’t represent everything that The Architecture Lobby suggests, but definitely the thinking and the work is very much a group effort, even if I drag them into a direction that they may not want to go.

But just to say I think that most of you know that there was an event at Penn that was organized by Billy Fleming, Daniel Cohen, and Kate Aronoff. We saw the picture with Naomi Klein as part of that event. And at that event I was really primarily arguing for the fact that as architects we need to organize. We do not need to primarily give a vision of a design future to which we have no responsibility and no knowledge, and where we actually think architects might lead that discussion. We need to organize so that we can speak as a united voice. I really believe in that.

But I do want to suggest that, after that there was a lot of discussion about the lack of talk about design in that. And so in some way I want to build on that discussion and kind of revise the topic of my talk today to really insert design and think through design as an organizational but also as a spatial act.

So this talk will be divided into three different parts. One is Organizing Designers, the second is Defining Design, and the third is Designing Citizenship, architectural citizenship.

So for the first, Organizing Designers, in some way this is a repeat in a very collapsed way of what I really do want to emphasize and which was talked about at Penn. And to really kind of emphasize that what we don’t want to do is suggest if we talk about design or you know, think about our work as what I would consider to be the kind of self-serving idea, or self-satisfied and self-aggrandizing and I think very misleading idea of many architects and designers about what they are contributing to the Green New Deal and the sustainable movement. This was a recent promotion in Architectural Record, you know, and this was just one of the many projects that then was shown about this new idealism, the actionable idealism by this particular designer.

So in lieu of this I want to be talking about and organizing designers in two different ways. One is reforming practice and labor, and the other is redefining resiliency and technology. In some way what these two things are doing sets off something that I think is important all the way through, which is if we’re trying to reformulate how architects behave and can participate meaningfully in changing our practice and changing the way we actually operate in the world, one is to internally reorganize our sense of architecture within the AEC industry and within the building industry. So it’s an internal reorganization, and that’s what the “reform practice and labor” is about. But the other is a rethinking about how we engage with the public, with the outside world. You know, kind of an external rethinking, and that is what the redefining resilience and technology is about so.

So, for reforming practice and labor, I want to emphasize and I’m going to go through this quickly, but I really really want to suggest how important these quick bullet points are. So, if we actually are thinking about a new practice and a new idea of architectural labor, we need to unionize. No question about it.

The second is we need to work with and realign with the construction unions. And here I really do honor Damian’s work in just transitions. But if we don’t unionize ourselves and speak as a united voice, we are not going to be able to work with and rethink and realign with the construction industries that are borderline in their commitment to the Green New Deal to say the least. We need to cooperativize instead of competing against each other for a small pie, and for again a misleading sense of what it means to do “green work.” We need to cooperativize together so that we think about our shared research, our shared knowledge, and our shared impact. This is not the moment where we compete against each other and see other firms as the enemy, the enemy is actually the crisis that is at hand.

And lastly we need to insert protocols that derail the market-driven shaping of the human environment. That’s the large project and we need to think about that as the ultimate goal.

For redefining resiliency and technology you know, again this is how we need to kind of not just internally reorganize but rethink our project within the public. You know, architects’ role within the public. We need to reimagine resiliency and its procurement at all scale, which means not thinking about LEEDs whatsoever, but also I think as Billy Fleming and his fabulous article that he referred to here, we can’t think about this as a series of competitions for grants for a small pie, when in fact we need to be organizing the government. The state should be doing the work, not competing architecture firms for a small piece.

We need to embrace decarbonization as a social justice issue and not as a technological issue. We need to bridge between communities and policymakers to promote just transitions. We need to make sure that everybody who is affected by this work is at the table; this is a democratic process. Again, this is a large part of what makes the Green New Deal so different from other discussions about sustainability and climate change. And we need to develop models for large-scale adaptive reuse and retrofitting of buildings.

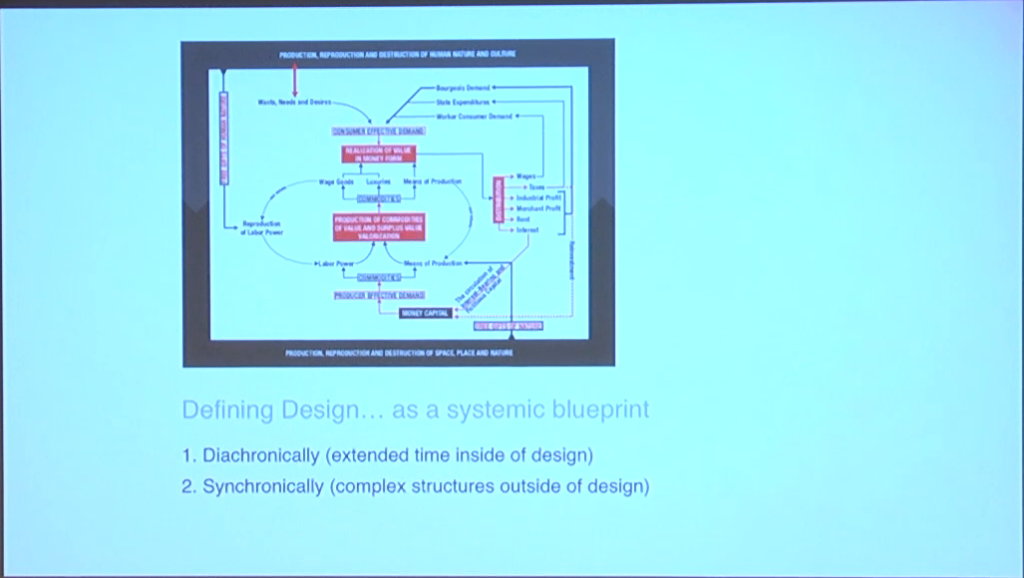

So then to move on to the second part, which is defining or redefining design. And part of that is really to think about design in a systemic way. We can really think about a redefinition of design that is in some way a blueprint that understands where we are in a very very complex system, and part of that complex system is neoliberalism and certainly capitalism itself. We’re not doing our work if we understand ourselves as having a defined task within our particular discipline that has formal design as its calling. We can no longer do that.

So, again I want to kind of emphasize that there are two parts of this. We’re trying to change the nature of architectural design and what it does. The first is what I would be calling diachronically, which is understand the work of architectural design over a temporal period. But that’s within the discipline, so we no longer think of design as given a program, designing it, handing it off, having it built, taking a picture and going “goodbye.” It’s a much longer process. But that’s one that really makes us think differently about our practice internal to the discipline.

But the other is synchronically, which is to understand how structurally, we are embedded within a much larger system of power, economics, social norms, within which we need to be thinking about.

So, just thinking diachronically, I think this is all kind of very obvious. But if we’re trying to think about design as not just a six-month [indistinct] that we do on our boards but something that truly understands where our resources come from, the embedded carbon footprint, but also the labor that’s involved in many of the products that we think are actually beneficial. This is just an an image of cobalt extraction that happens in Africa. And when we think of our smart phones that rely on cobalt, we need to think about the labor extraction and abetted energy, way way way at the front end of our design process before we actually put pencil to paper. This is an app that is designed by Kieran Timberlake called Tally that allows us during the design process to understand many of those conditions.

So this is at the front end of the design process. At the back and we also need to understand post-occupancy. And as long as the public, the world thinks that we walk away when our buildings get built and have taken our picture, it’s a problem. And one of the things that I think we might think about is not giving any design awards whatsoever until we’re five or ten years out. I have this image here of the Gherkin, Foster’s building that won a Sterling Design Award in 2004. And within five years we knew that all of its claims for sustainability were basically untrue. So we need a much longer timeframe to see what’s up front and what’s at the other end of our process.

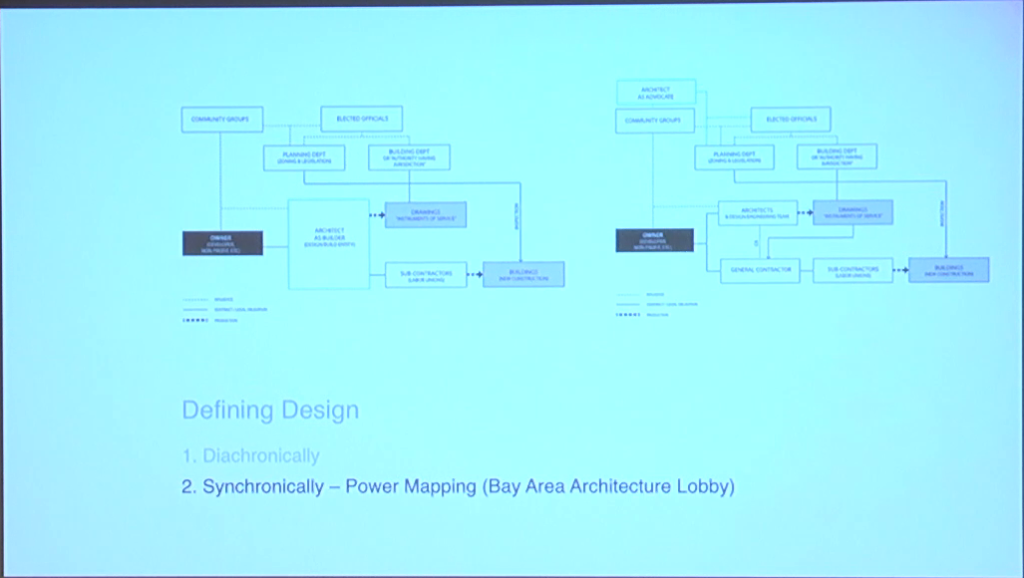

Synchronically, and again kind of understanding where our work is within a larger network, one of the things that architects can do when we’re thinking about a redefinition of design is power mapping. And I have an example here. These are just two images of multiple ones that were put together by the Bay Area chapter of The Architecture Lobby. This is Ashton Hamm, Alice Armstrong, and Meghan McAllister’s work that is really trying to understand exactly how housing, affordable housing, is brought to the fore and how different power players operate within that system, and then trying to reimagine how architects could insert themselves in a different process. So power mapping is one.

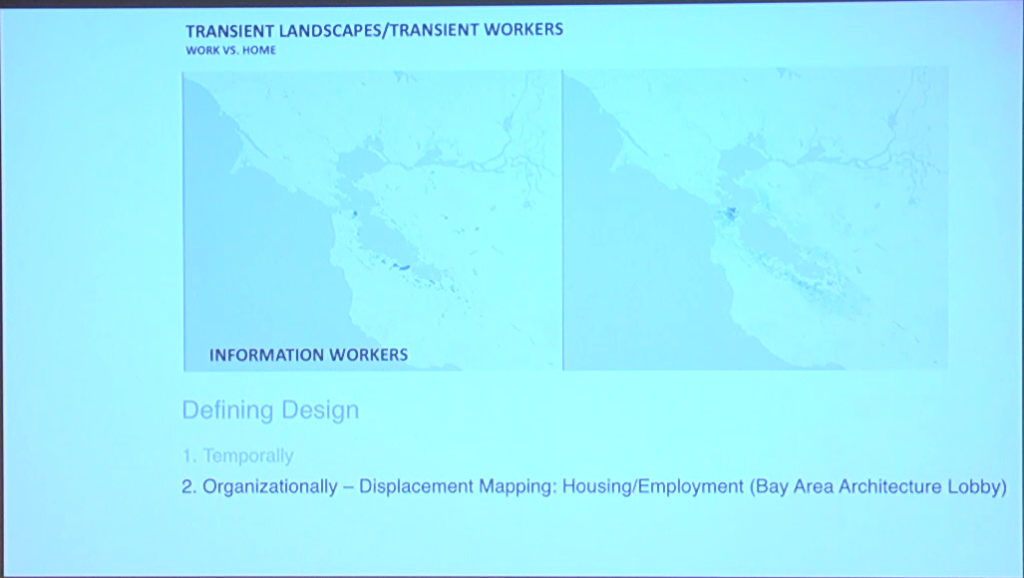

But the same group of people, again in their work on affordable housing in the Bay Area, were doing a mapping of where people work versus where people live. And again this is just two maps that identify the information workers, but they did it on service workers and they did it on construction workers, that actually shows exactly the difference between what a kind of dream idea of a life is and a dream job is in relationship to the difficulty of where you’re gonna actually live and be able to afford in order to do that work. So again, we can talk about mapping—I’m calling this displacement mapping—but that again is part of the work of what a redefinition of design for architecture might be.

So then the last thing that I want to talk about is Designing Citizenship. You know, which is to say design does have a role within academia, and how we teach design in academia in some way sets us up to be the architectural citizens that will actually do the work that we are calling for and that the first two parts of this talk have been and done. You have to create that citizen who knows that that work is important, who knows how to formulate it, and is committed to that work. This is the role of the economy, and it’s not happening now.

So again I think there are two ways of thinking about that creation of the architectural citizen and the role of the economy. One is again to kind of rethink how we understand what it means to be an architect within the larger industry, how we relate to construction, how we think about research. But the other is then how we actually create an architectural citizen who goes out into the public and thinks about their role and thinks about design in the capacity of a conversation with the public.

So very quickly, for the first one where we’re designing the kind of architectural citizen, this is a project that I completely admire. I want to say both these projects that I’m going to show are way before the Green New Deal. They don’t actually demonstrate how we educate for the Green New Deal. I do think Billy Fleming’s studio is very much doing that. I look forward to seeing the result of that work. But I think this is an example of how to rethink what a studio looks like so that we’re prepared to do that work.

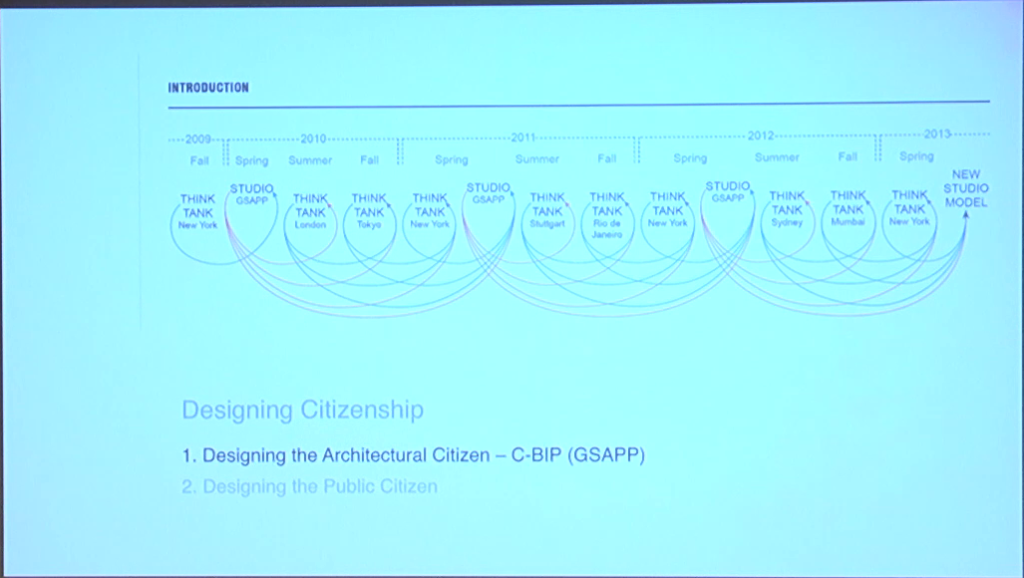

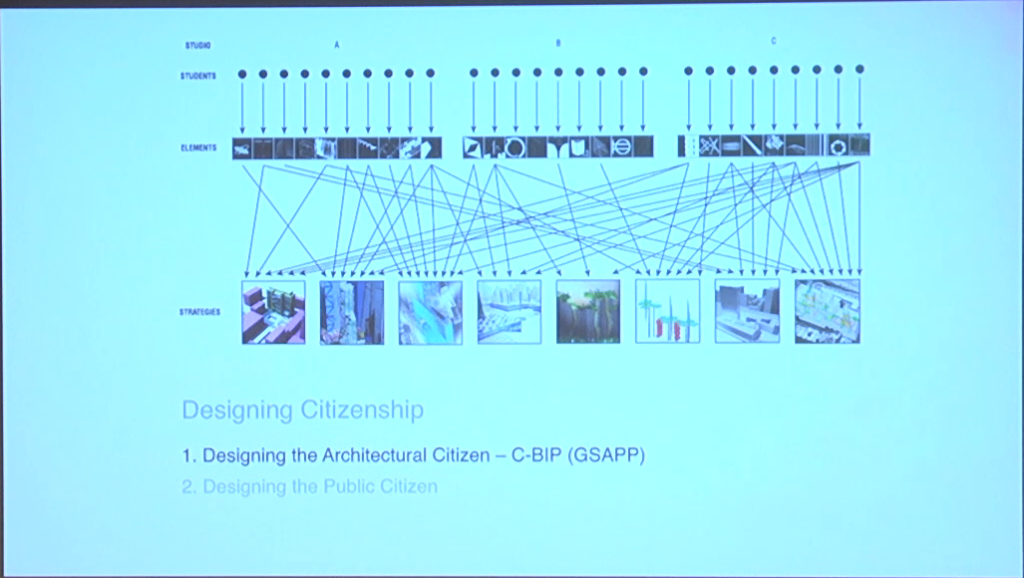

This is a studio that was called C‑BIP. C‑BIP is [Columbia Building Intelligence Project]. And it was unusual in as much as it combined a number of things. One, they saw this as happening over three different years, and so this wasn’t the normal “do this in your advanced studio” where you do it for one semester. They organized it so the students can come in early on and over their three years at Columbia work on this. It took three critics. They came together so they had a much larger group. That’s what allowed them to actually have a larger impact within the school itself. But they also saw the studio embedded within what they called the Think Tank exercise. And so they held three Think Tanks every year, within which the studio was embedded.

The way that studio was run was interesting, which was that individual students—again in these three groups—were asked to design a particular element that would in some way help the sustainability and the health of existing buildings. So two interesting things about that. It was a component, it wasn’t a building; and the buildings were existing buildings, so they weren’t designing existing buildings. So they designed those elements, and then those elements allowed different students to find strategies that they would apply to existing buildings in New York.

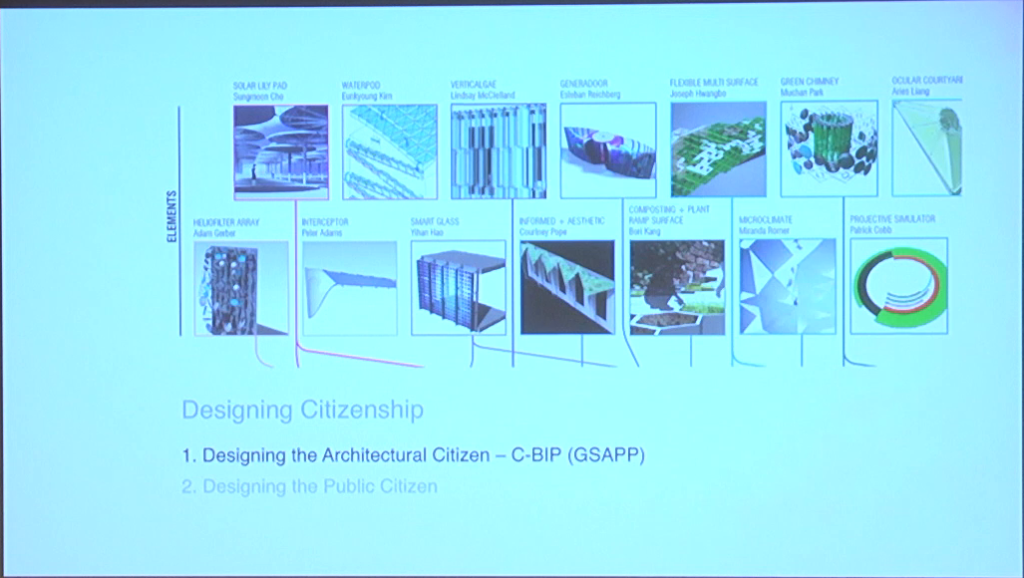

So for example these are some of the elements that the individual students designed that had to do with facade work, had to do with ventilation, had to do with how you can actually use the facade to grow things, how you can have smart facades. These were all individual students.

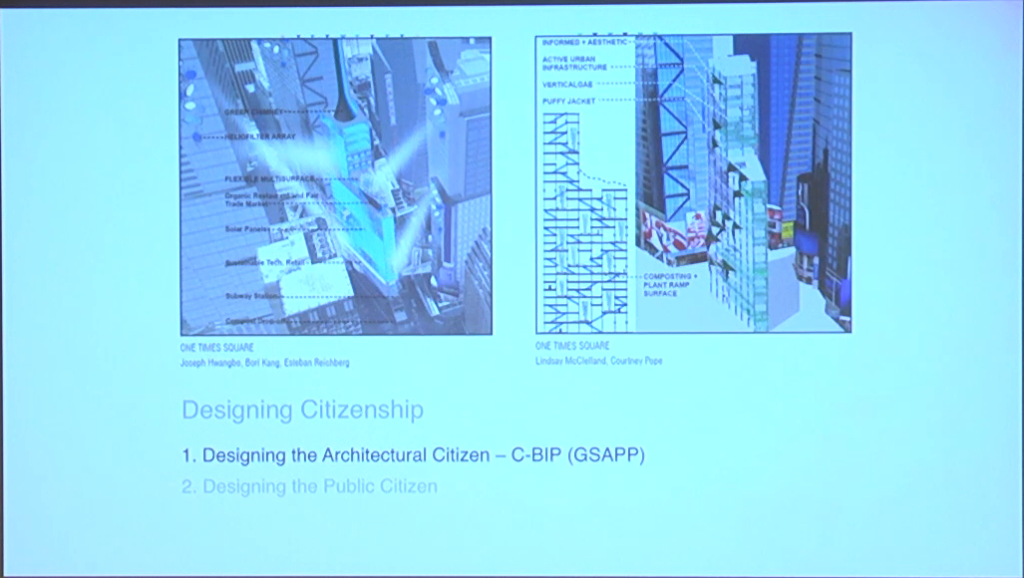

But again those elements, after they combined together to work in a group and left that individual design work, worked in a group to think about combining those strategies together on an individual building. Which then looks something like this. Those students had to come together— But one of the things that was interesting is that those original components that came with a kind of operation manual, when those elements were combined in different strategies they had to be modified. And so the students then had to go back to the original owners and like an IP contract argue for and rewrite the manual so that those component pieces could be changed. So in some way it’s a very interesting model about how one needs to work as a group, but also think about the design as not about a new building but actually retrofitting healthy buildings and seeing your design elements in other ways.

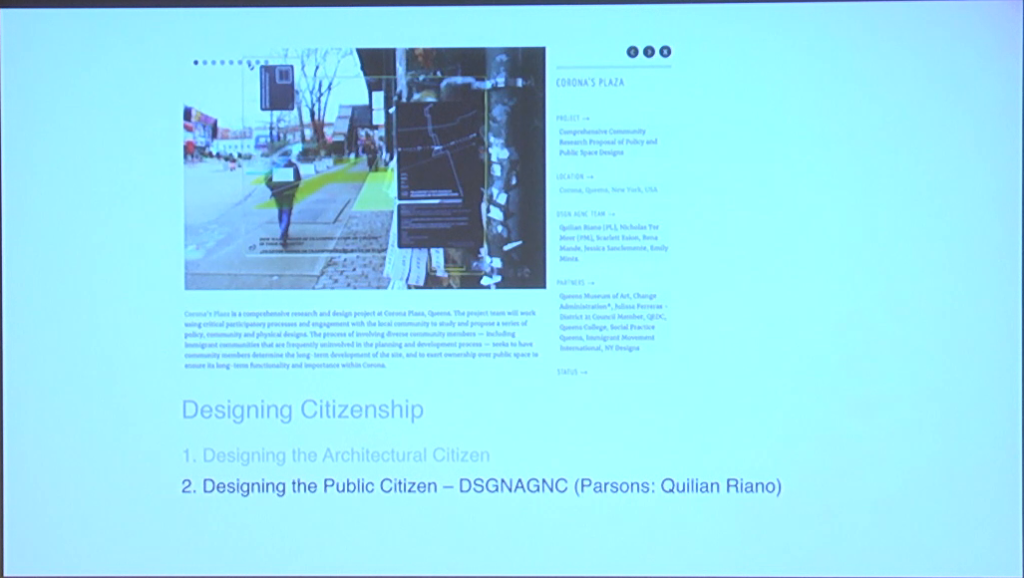

The second one that I’m going to look at here, and this will be the end, is again a studio that was done at Parsons. This was led by a group called Design Agency which is really Quilian Riano’s work. This was a project that he had a grant to do but he was teaching this as a studio also at Parsons. And this again is kind of teaching the architectural citizen to engage with the public and think about design as an aspect that allows you to communicate with the public.

So this was a project in Corona Plaza. And it basically started out with what he called Action 1, which was diagramming and mapping, and this was getting the people in the Corona area to think about what mattered to them, what functions there were, who was allowed in spaces, who wasn’t allowed in spaces, who had priority. And this was done as group work, so diagramming and mapping.

The second was to have a shared game where the people of Corona Plaza would begin to participate in the negotiations of how you really create a commons. If you do this, who’s excluded? If you do that who’s excluded? How do you come together? So it was literally a game that people brought to the organization. Here they are playing that game, doing the mapping of that game, thinking again about the give and take of what that conversation is like.

And again, that then yielding something that is actually built in the Corona Plaza, which itself was in some way a public event that invited the public to come, but was also kind of at a scaled role a map of all of the constituents and all the different components that really come together when one is thinking about making a public space.

So let me stop here, but I wanted to say that one of the things that I have been most struck by as I participate in these various Green New Deal symposia—Penn, then there was one at the Queens Museum which was an event that was organized by Reinhold Martin in the district that AOC was a part of—was very much hearing how bottom-up groups one, are the ones that we need to be paying attention to, that this is not primarily a top-down thing but if we really are thinking about just transitions it’s a bottom-up. But that bottom-up communities are begging architects to be at the table. Part of me resists this idea that they think that we’re going to visualize their future for them, which I think is irresponsible. But I very much understand the calling that we need to work within the communities in order to do exactly this kind of work.

So again, I want to suggest that the main thing that we need to be doing is working as a discipline, as a profession, as a unified voice, so that we sit at the table of policymaking and are believed as not just ambulance-chasers for work for ourselves but as people with knowledge and whatever embeddedness in the community, and our design expertise within the community is absolutely essential. Thank you.

Further Reference

Climate Futures II event page