My name is Anil Dash. I am cofounder of a company called ThinkUp, and I’m a blogger. Which is a great, fun way to introduce myself these days, because it’s a little bit like saying, “I’m a Facebook user,” right? It doesn’t really say much about me. But, the reason I still say it is because ten or fifteen years ago, when I started blogging, that actually meant something. It meant that you were part of a community not just of the people that were going to share their lives online, or post photos to look at for one another, but that we were also building the tools and the technology.

It was a very small, close-knit community. And people in that community of early bloggers that I was part of would go on to build things like Twitter and Flickr and Blogger and LinkedIn, and then later on stuff like Tumblr and Foursquare. All these different apps. So it was a really really fertile time. It was like a small close-knit community like the one that comes here, all talking about their ideas and things that we had learned. So, stuff like if you change a setting for whether the default of information is public or private, that radically changes what people will share. And if you change whether it defaults to photos or text, and whether it stays forever or is just ephemeral and disappears, these things really really impact what people share and who they share it with.

And so we found that features define culture. Software influences culture at a very deep level. And that sounds obvious now in hindsight, but it wasn’t obvious to all of us. And naturally what happened is those tools took over. I don’t need to tell all of you about this rise.

But there are names and voices and ideas that weren’t as well-known. I think of one of the early stories that stuck with me all these years is my late friend Brad Graham had one of the earliest blogs, a site called Bradlands. And one of the first things Brad did—and this is in 1998, very very early in the social media era. He would organize every day on World AIDS Day an observance across the then-entire blogosphere (because that was a thing you could do back then) of everybody participating in observing this day and speaking up for a community.

And notably, his voice, an LGBT voice, was one of the most prominent and influential voices right from the beginning of the medium. It was always a diverse medium. And even as those projects and those little apps that people were building turned into real companies, we had investors and people that were involved that were from the community. Folks like Joi Ito, who you heard from earlier, were people that used the tools, and that’s why they wanted to see them succeed. And the mandate from them was “get as many people using these things and connecting, expressing, as possible.” And in that way, the modern social web was born. And interestingly, almost the entire rest of the tech industry shifted to focus on what had been built and on learning the lessons from that world.

And this is a striking thing, that this small group of innovators caught a tiger by the tail. Because to that point, keep in mind, we had thought software was basically just tools. It was like, spreadsheets and things that you’re going to use to complete a task. It wasn’t a way of connecting with one another. But as it turns out, the highest and most important use of software would turn out to be the thing that humans have been doing for ten thousand years. Building communities, connecting with one another, communicating in more efficient and effective ways. All of the prior several decades of computer technology history had sort of been prelude to what they were really meant to do best.

And the success of all those social technologies is something really really striking to me, because what it’s meant today is most of us (all of us in this room, certainly) by the time we reach the end of our lives, will have spent at least three years of our lives with our thumb on the glass of our phones. Think about that.

And we know what Google and Facebook and Yahoo and all these folks, we know what they get from it. They get our attention, and some of that they auction off to advertisers. And good for them. That’s great. But what do we get from it? What do we have to show for three years of our lives invested? Put more sharply, what is meaningful about all this time we spend online?

This question haunts me a lot, because I can now look back at a decade and a half of my life, and I’ve got a young son, and I know pretty soon he’ll be old enough to be able to read what I’ve written. And I think a lot about what we have to show for it. I think one of the recurring conversations that’s happened here today is thinking about self-reflection and observation of what’s meaningful to us.

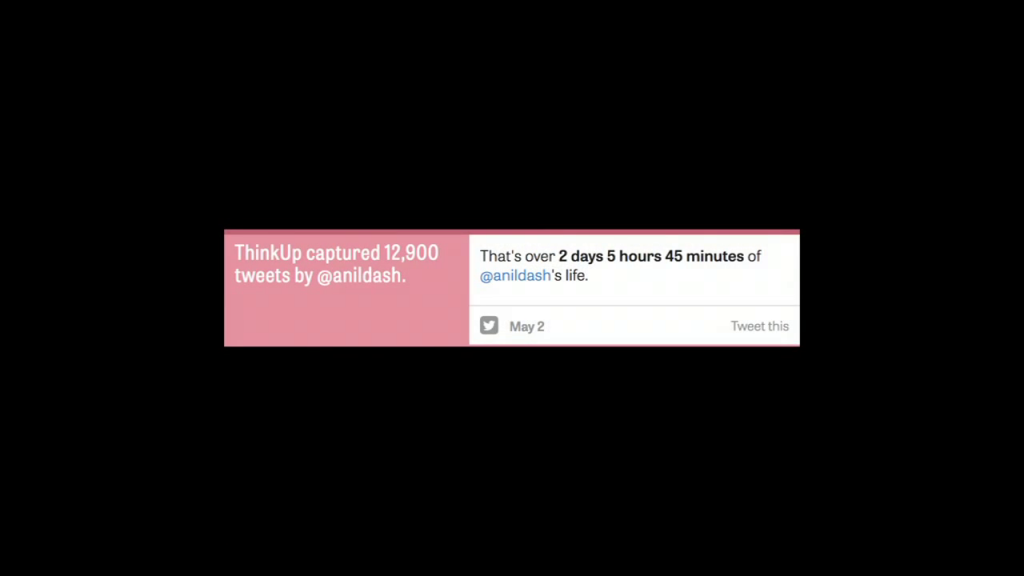

And this was part of the work that I set out to work on with my cofounder Gina Trapani several years ago, building an app to answer some of these questions. And we built this app that was just sort of answering things like, how much did I spend tweeting? In my case this was six months ago. I’d spent like over two days tweeting in my life. And that was just outbound, not counting how much I read coming in.

But there were other questions we wanted to ask like, how much of the time that I’m talking on my social networks am I talking about myself? And is it more or less than it was last week? And what does that mean? Is that good? Is it bad? Should I be promoting myself more? Should I maybe be listening a little bit more?

How often am I thanking people or congratulating them? And why isn’t Facebook telling me that? Isn’t that something that they could tell me? They have all the data, right?

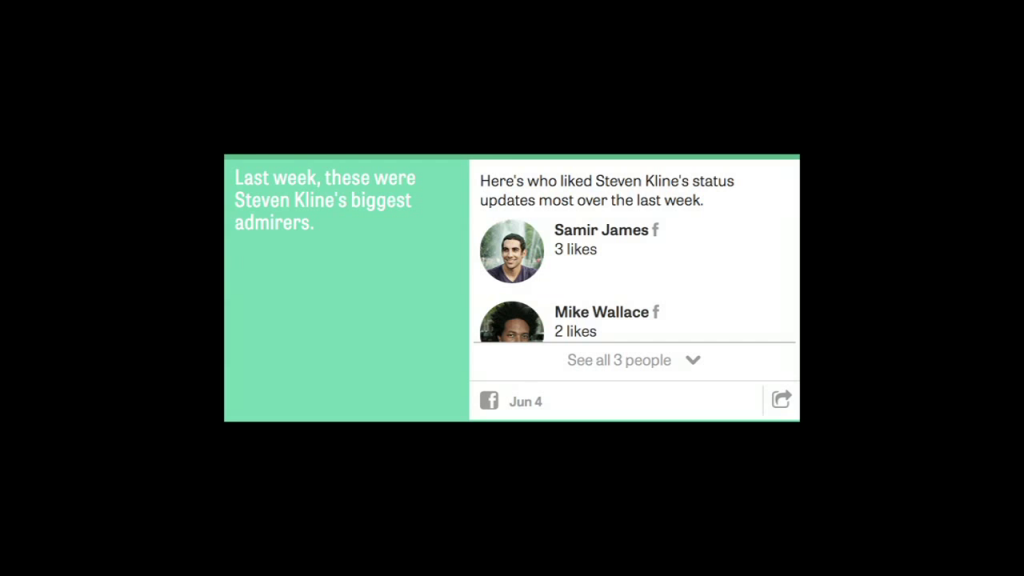

Who are my biggest fans? In my case, being an Asian son, my mother is my biggest fan on Facebook. That was inevitable. But, for some people it might not be as obvious, and so that’s something you want to tell people.

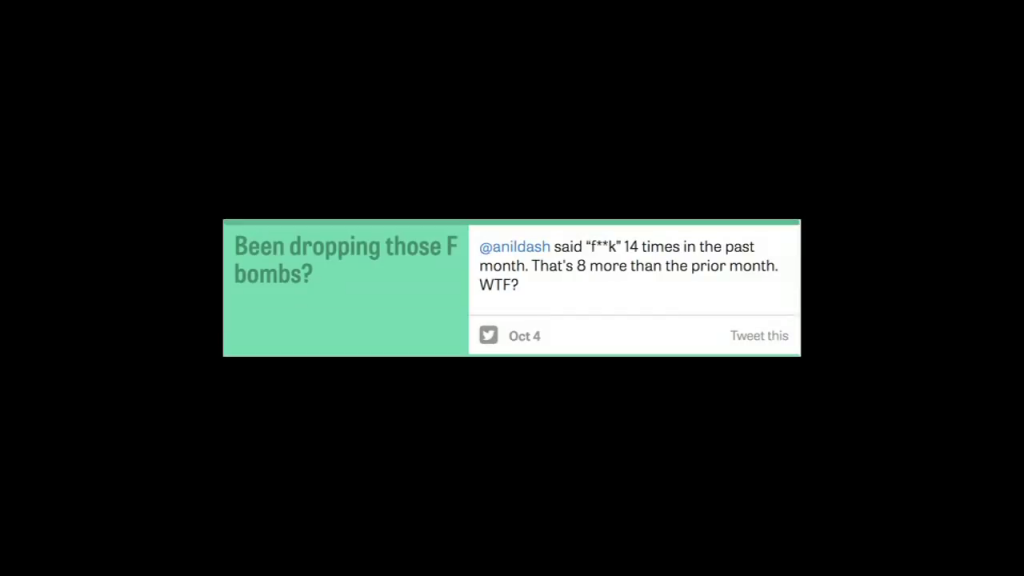

And then as a New Yorker, how much am I cursing was a pretty important question. And was that going up or down? And again, with my mother watching, should I probably tone that down a little bit?

These are the questions I had about making my time meaningful. Some of them were silly. Some of them were frivolous. But all of them were meaningful, because they had me thinking about what my time spent on these networks was going to mean.

And this is the point where I’ve talked a little about about an app I’ve built, and I’ve dropped the names of folks that I came up with that are wildly successful, where I’m supposed to talk to you about how we all lived happily ever after. And social networks helped people have a revolution in Egypt. And isn’t that great? There’s this really interesting sort of triumphal streak in the tech industry, where we say, “Now you can put cat videos on YouTube. Thank me later.” That’s great. I’m all in favor of cat videos.

But then the self-reflection has to continue from that point. And what I looked at is what happened to the technology industry when it shifted its focus to trying to ape the behaviors and patterns of the social web, of social networks, of mobile apps. When the entire industry decided this is what its priority was going to be, and the new wave of companies came along to follow.

And this is where hopefully the conversation gets a little uncomfortable. Because honestly, a roomful of people as comfortable and privileged as all of us, if we’re talking about rebels, we’re talking that revolutions, we’re not the ones on the bottom coming up. This room should be pretty uncomfortable about what it means. We should be thinking about what we have to change in ourselves. And I say this particularly to those of you who like me are in the tech world.

One the most uncomfortable places to start is the terms of service. These are the things you don’t read when you upgrade on iTunes and it says “I agree. I read these.” And what they say in them, essentially, is they can take the conversations you’re having and do whatever they want with them. Change them, delete them, delay them, slow them down, erase your account for no reason or for any reason at all. There’s no recourse, there’s no appeal.

And the reason this is especially striking is because the majority of conversations that are taking place in our country today are taking place through the mediation of a small handful of giant technology companies. The majority of conversations are taking place under the terms of service of a small number companies that have no recourse to you. And this is true even for civic conversations. We see the President have a town hall at Facebook. We see it during disasters, municipalities tweeting out information about how to get rescue supplies.

Now listen, I’m glad those social networks provide those services. I think it’s important for the dialogue to happen that way. But it can’t be the only way for us to have public discourse. Online, we only have these spaces that are owned by private companies. We don’t have public parks.

And this wouldn’t be as big a problem if the tech industry had a sense of what I think of as old-fashioned civics. You see, that civic responsibility that happens when a local car dealership sponsors the pee wee football team. There’s a sense that there’s a community that they’re serving. Well, tech industries are pretty young and full of very very privileged people. And they’re actually pretty lousy at thinking about what their civic obligations and civic duties ought to be. In some cases they actively shirk them. This is a strong statement. Let me talk to you about how it actually [?] impact in the real world.

The tech industry today is proud to trumpet the fact that smartphones are nearly ubiquitous around the world. But if we look at the tech industry itself, who gets a chance to sit at the table, build these tools, and profit from their creation? The statistics are pretty alarming. As you might imagine about the population of the United States or California, where most of these tech companies are based, is about 50/50 male/female, a couple people of other genders. But really, overall, it’s pretty balanced. But within these tech companies, it tends to be very frequently 2⁄3 of the employees are men. In many these companies if you look just within the technical staff, the people who make the products and actually determine the culture of the company, companies like Twitter, 90% of the employees are men.

Now let’s look at it from other breakdowns, like ethnicity. Obviously, white men and Asian men are doing pretty well in technology. A lot of these companies look a lot like this room. But take something like a state like California, where 40% of the population is Latino. Within technology companies, it’s very common for 2% of their employees to be Latino. Same thing with African-Americans. 12–14% percent of the American population; within technology companies, again 2% of their technical staff is frequently African-American.

And this at the same time as they’re crowing about how high adoption is of smart phones by minority populations. And the implications of this are that the systematic exclusion on the creation of the tools, as we said, impacts the culture. So it is no doubt—it was inevitable that on an average YouTube video that could be about how you made a peanut butter and jelly sandwich, you’ll start to see strings of racist comments. And people say, “Oh, that’s just how YouTube is.” Or systematic harassment of people on Twitter. Right now, there’s a group of angry misogynist gamers trying to chase away the majority of video game players who are women from their industry, from their little clubhouse. And there aren’t good tools for preventing that abuse, even as women are getting chased out of their homes, because most of the people who are impacted by this don’t have a seat at the table to create these technologies.

And it’s not just about these abuses happening because people in tech are bad. They’re not. They’re good people. They’re well-intentioned. They want to help people. But above all, they’re meant to pursue efficiency. And the way efficiency is designed in the tech industry today is around this model that looks like an Instagram or a WhatsApp. Instagram, when it sold for a billion dollars to Facebook, had about a dozen employees. WhatsApp, when it sold to Facebook for twenty-two billion dollars, had about twenty employees. That’s the efficiency they’re optimizing for.

I’m not anti-tech, because we can look at good examples in tech. Something like one of my favorite New York companies, Etsy, building a marketplace that is explicitly inclusive, where people can trade crafts and things they create, and sell to one another. And the majority of their creators are women. They’ve done a targeted and structured way of actually encouraging women to participate in Etsy as employees. And it’s working.

So I’m not saying the tech industry is bad. I’m saying how we define what success is and what our goals are for efficiency, we have to be thoughtful about. We have to be mindful about. Because when we look at the implications of what tech impacts. Things like our privacy. It affects all of us every day. It’s not just that your nude pictures might leak out from Apple servers, although obviously that’s a serious issues. But also, even though the tech industry rightfully objected to the NSA violating our civil liberties and monitoring all of us, they also made it possible. If we hadn’t put all our eggs in one small basket, it wouldn’t have been so easy to collect them.

And so what I’m asking for all of us to do that are in the tech industry, and for all of you who are just consumers of tech to hold us accountable to do, is encourage us to respect the institutions that tech could be paying attention to. I look at companies like Uber, which is the current darling of the tech world, getting hundreds of millions of dollars in funding. And they’re trying to make it better to flag a car down so you can travel somewhere. And everybody’s in favor of that.

But the way they’re doing it is systematically going into new cities and violating transit policy, violating taxi laws, while they’re making cars available. And listen, I don’t care how out of date the regulations are, you can’t have a precedent set where industries are built on violating laws at large scale. These rebels building tech start to look a lot more like robber barons when you look at it through that lens. And it’s not too late to fix it, but only if we hold them accountable.

But there are exceptions. There are still a lot of apps and a lot of websites that are made by one or two folks working on their own, by mom and pop companies. But I ask you, all of you in this room are the kind of folks that say, “Oh, I’d much rather go to an independent coffee shop than that big chain. I don’t eat fast food for every meal. Sometimes I have home-cooked meals.” How many of you know who made the apps on your phone? How many of you know who those people are? Are any of the apps on your phone made by minorities? Do you know who? You certainly are the kind of people that say, “Well, there’s a new restaurant in town and they’re new immigrants, and I want to help them get a foot up so I’m going to go and patronize that restaurant.” Do you do that as a consumer of technology? Couldn’t we?

Because there’s this question about what we care about in the tech industry. And we are very very eager to take credit for the positive things that happen from connecting people together, and we should be. I’m proud of the role I’ve had. I’m proud to see my friends have had incredible impact.

But we can’t take credit for the good without also taking responsibility for the bad. And I look at something like twenty-two billion dollars spent on WhatsApp. That’s great. It’s a very useful messaging app for people. I’m glad they find value in it. And I think about one million unemployed African-American women in this country, each of whom could get a $20,000 training scholarship to learn to be coders or programmers or whatever they want to be in their careers, for the same cost as one WhatsApp.

So I say to the technology industry, if you want to change the world, change the world. Don’t wait. There’s an urgency here. And I ask you to hold me accountable, too. Because I was complacent for a long time to coast on, “Well, aren’t we doing great? Isn’t everybody happy about these networks they’re using?” And then I spent some time to reflect. And thought about what’s going to last. I’ve now had maybe ten or fifteen years to look at what my life online is going to look like. But think about today’s technology. The apps we use, the services we use. And look forward ten or fifteen or fifty years to what we tell our children, our grandchildren, great great grandchildren about the rise of this industry, about the rise of the influence of this tech.

Because unlike the other media like traditional journalism that had a role that was enshrined in the Constitution, clearly defined in its relationship with our civic institutions, we’re still negotiating what the role of the tech industry is going to be. And believe me, the tech industry will be a fifth branch just as much as the press is the fourth branch of government. There is a check and a balance that is happening that has not taken place yet, for the tech industry to use its power for good. But only if all of us hold everyone in tech accountable.

And so I want to make a call for all of us, every single time we put our thumbs on our phones, every single time we share an image, think about first, what are we doing for ourselves? What will this mean to us in a few years? Will we be proud of what we shared? Is the message we’re telling one another the one that we care most about? And then for the apps and the sites and the services we use, to say to them, “I expect you to live up to your obligations, commensurate to the incredible privileges and rewards that you’ve been given.” And for all of us together to look at this world that’s being shaped by these new technologies and say we can do better. Thank you.

Further Reference

This session’s page at the PopTech site.