If you see this diagram over here on the monitors, sometimes people think about cyberspace in a very simplistic term or way. They think about it as people and data.

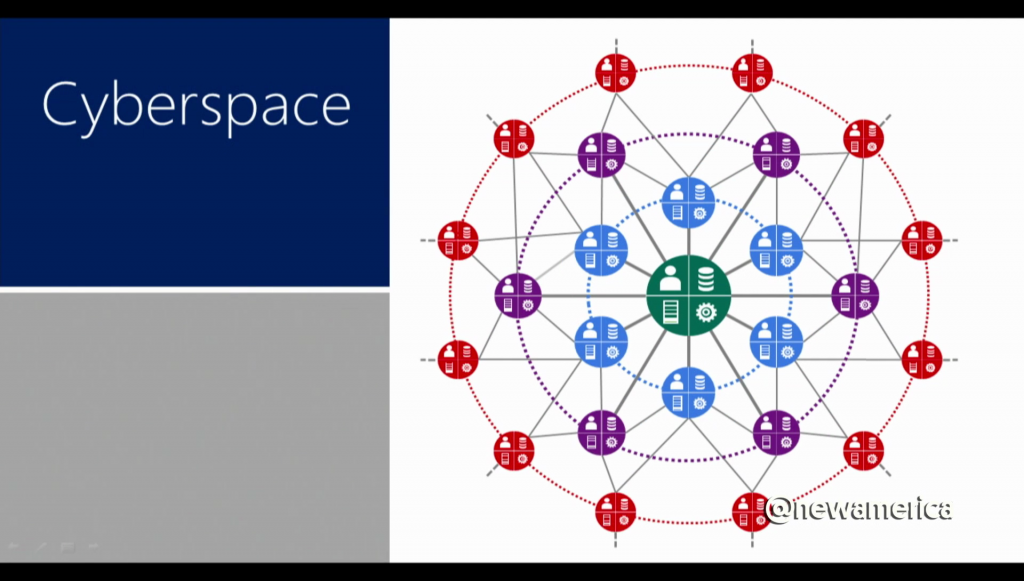

And sure, cyberspace is about people and data. But it is also about applications. And devices. And the indirect and non-obvious relationships between all of this.

It creates a very complicated and exciting ecosystem. One that is capable of dramatic innovation, and dramatic exploitation. And we need to understand that as we start to think about the next decade ahead.

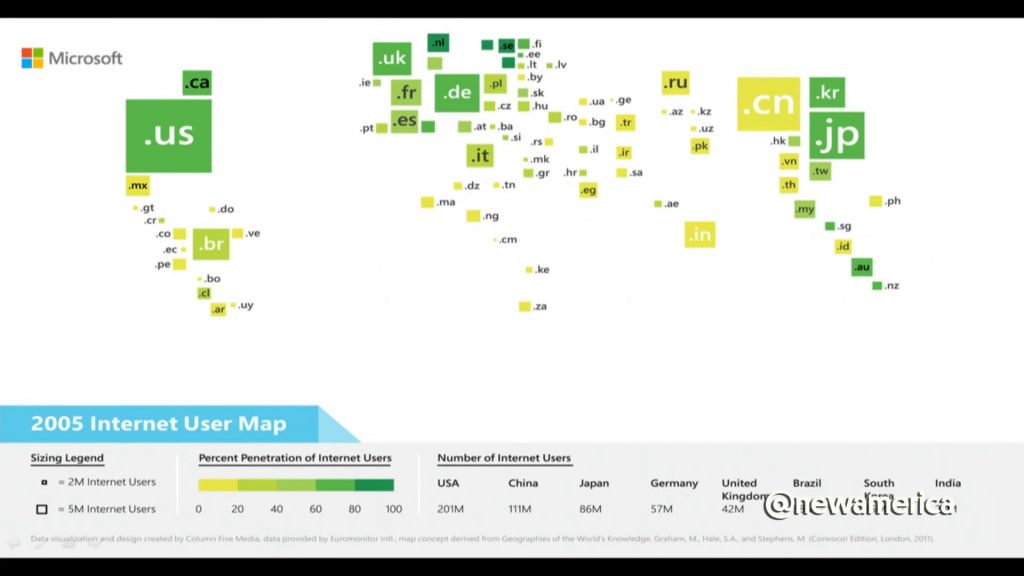

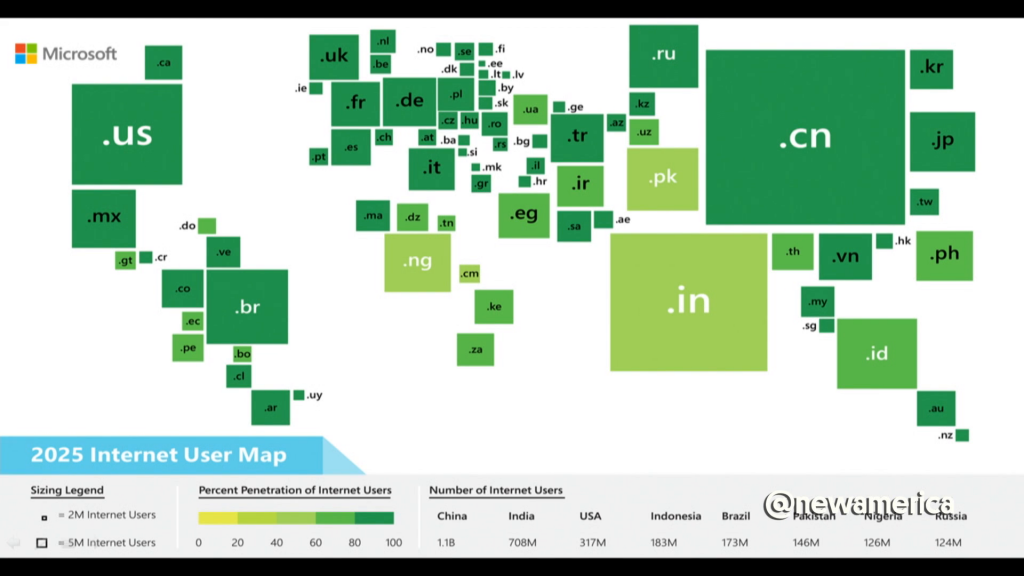

This interesting map of little squares that you see here is what the world looked like in the year 2005. You all remember the year 2005. That was when Uber was still just a German word and not a global transportation app. But if you look at this map you see the size of the squares on the map actually represent an online population of a country. And whether the square is light or whether it’s dark indicates the amount of penetration for broadband in that country. So you see China, that little yellow square with “.cn” on it over there had about a hundred million people online, or a hundred and ten million online. And that was about 20% of the population. So they’re yellow. The US at this point had about two hundred million people online. And that was a much more significant part of the population.

2005 was an interesting year. This is the year I sometimes think of as the great cybercrime hook-up, where spammers met phishers, and we started to have a very diverse, differentiated, and dangerous cybercrime market, one that we still feel the effects of ten years later.

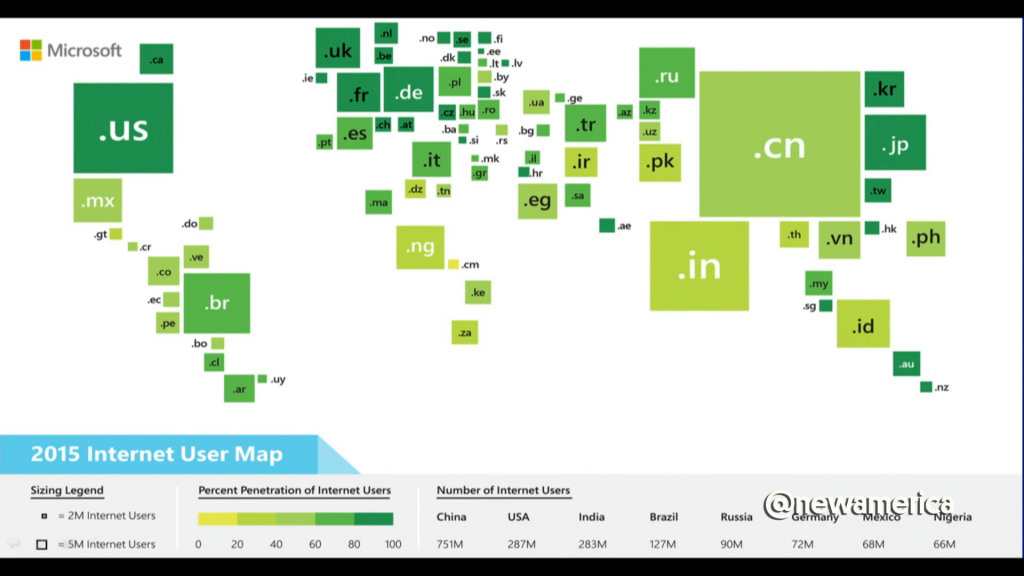

Our world today is much different. A lot more people online, when you look at this map. It’s also a lot darker green. Today, we have over three 3.4 billion people online. That’s fantastic. We also have eighty-five countries passing cybersecurity laws and regulations. Wow. That’s a lot. What gets passed in the next three years will probably shape cyberspace for the next thirty, and we need to think carefully about that both as the US, and as the international community. What is the right approach?

We have about sixty governments today who are on record for using cyberspace for domestic and international surveillance. And we have thirty governments with formal military plans and programs in place. Forty percent of the population that you see on this map is covered by an Internet of Things strategy. You do not live in one of those countries. This is really going to change.

Today, cloud computing, which you don’t really see reflected on this map because it’s about connectivity, is growing at a pace that’s hard to match. At Microsoft, our cloud computing and storage capabilities are doubling at a rate [of] every six months. That is power, and power that is starting to be used by people and enterprises and governments around the world.

So, what happens when we spin forward the next ten years? This world starts to look incredibly different. This is a world of over five billion people online. And I think what’s really dramatic about it in terms of opportunity, in terms of diversity— Take a look at the global South. Look at the amount of people coming online. Take India, for example. In the next ten years, there will be 700 million new broadband connections in India. That is amazing. The same time in Europe, you’ll have 124 million. So, the pace of change, the use of technology, innovation [is] going to be dramatically different as we start to move into the future.

How do we build the legal constructs that allow for free markets and the digital solutions that enable sovereignty for nations? How do we balance that? The public policy debate of the next decade is going to be defined by our ability to balance personal freedoms and national security.

I want to talk a little bit about what some of the diffusion actually means for us as we move forward. The diffusion of power is really phenomenal in what it means for individuals. You know, we had that 60s mantra, “power to the people.” Well today, you can go online and create amazing disruptions, amazing advances, that governments are really not equipped to deal with.

Cities today are taking on power that they haven’t had since the ancient world. The UN projects that we will have around forty-nine megacities over ten million by the year 2030. These will be cities will making be making decisions for their populations similar to that of governments, in terms of technology and use. We’ll also be in a world where multi-stakeholderism will be how we really make decisions, mainly because of technology.

I mention the diffusion of insecurity. This is something we need to take a real hard look at and understand. When I talk about the diffusion of insecurity, I don’t mean that things will be less secure. I mean people will feel less secure. You think about disruptive technologies, which is something the tech industry loves to talk about. “We’re breaking down barriers. We’re changing things.” That is tremendously exciting. But it also means that jobs change. Old jobs go away. How do you prepare for the new jobs? What are the new skill sets that need to be developed?

When you look ahead to the year 2020 or 2026, we have some real education gaps to overcome. The developed world will be creating around six million science, technology, engineering, and math graduates. And the emerging economies will be producing around twenty million. How are we going to compete for those resources? How are we going to get the right skill sets? You know, what’s happening today when you think about the future of threats is that technologies are not aiming at things like operating systems and apps, they’re going down into stealthy places like hardware and BIOS and memory and different places.

And they’re also contemplating integrity attacks. As you move to a world where more and more of your life is being converted to digital capital, integrity takes on a whole new risk. And that’s something I would say we’re not really well-invested in as a policy and technology community to understand what that means.

The other area is what I call surveillance societies. We’re going through this really interesting phase where we’re putting sensors on everything, and it’s super cool. You can understand things now at a level with big data and analytics that you could never understand before. But how do we make sure that the same things that we’re doing for efficiency and manageability don’t get translated into things that become surveillance platforms? What is the public policy balance in that space?

There’s also the challenge of cybersecurity norms. Cybersecurity norms kinda went mainstream in 2015. The government’s starting to talk about what is the appropriate role of a government in cyberspace when it comes to military actions or attacks. And what is the role of the private sector in this space? I think you will see great movement in this space over the next decade, and it is something that we as a policy and technology community have to learn to talk to each other about.

The recent experience with the Wassenaar Arrangement was a key example of that. Governments did something that seemed really appropriate. “Hey, I’m doing something to limit dual-use technology. Something to protect people.” And it turns out it was really not a good idea, because it actually made people less secure because it prevented the movement of security technologies, sometimes even within a company. So, we need a better community, a better way to deal with insecurity. Platforms to be able to talk about these issues.

I would also say there’s a huge opportunity coming in the next decade. An opportunity with cyber to do things that we’ve never thought about before. The first and probably the most obvious one I think is economic inclusion. As Anne-Marie talked about before in terms of trying to understand diversity and bringing more people into the field, when you look at that map of the year 2025 and you see massive amounts of people coming online, to me that’s exciting. That means people are going to use technology in ways you and I haven’t thought about, because they’ll use them in different constraints, different bandwidth, different reliability situations, and new things will come out of that.

How are we making the right investments in that space? Is it all going to come from Silicon Valley? Is it all going to come from a New York, or where the venture capital lives? Are we going to go find the next amazing technology, the next amazing company? It may not come from here. And how do we deal with that and try to figure out how to innovate in that space?

The other area I would highlight is the domain of security and controllability. We’re moving into a world where we are more and more reliant on things like cloud computing. And as I’ve said before, that is a tremendously exciting technology with huge capacities for innovation. But, we have to understand security and controllability, and provide transparency for people to understand what that means. And what that means, in many ways, is we have to rethink our risk management strategies and frameworks that we have used in the traditional world, and find new ways of dealing with them when it comes to cyber.

The other area I would highlight is resilient and sustainable technologies. There is a lot of work going on around the world today to try to understand resilience. What is resilience? It is about readiness. It’s about responsiveness. And it is about reinvention. Today, I think we live in a world that’s really focused on risk management. And that’s good. You need that. That’s important. And we have a world that sort of thinks about reliability in terms of, “I can turn things back on.” But how do you really start to prioritize around learning, so that you thrive in the face of attacks or adversity, and you keep growing? That is a dimension of technology and of culture that we have to grow and incubate. That is going to be core in the next decade.

I also think that these same technologies will provide a huge opportunity for us from an environmental sustainability perspective. We’re doing work today with a group called 100 Resilient Cities, where cities around the world are trying to understand the dimensions of resilience. And it is fascinating to watch them realize the core role that things like cyberspace actually plays in a city when they start to think about resilience long term. Because it is not just, “Hey, I have a smart city and I get a dashboard of how my trash operations are going, or my water operations, or traffic.” But it’s about social cohesion. It’s about job growth. It’s about innovation and the future of the city and where that goes. And again, this is going to be a dimension of cyberspace that we haven’t really thought about that much, and I think we really need to put a lot more emphasis on.

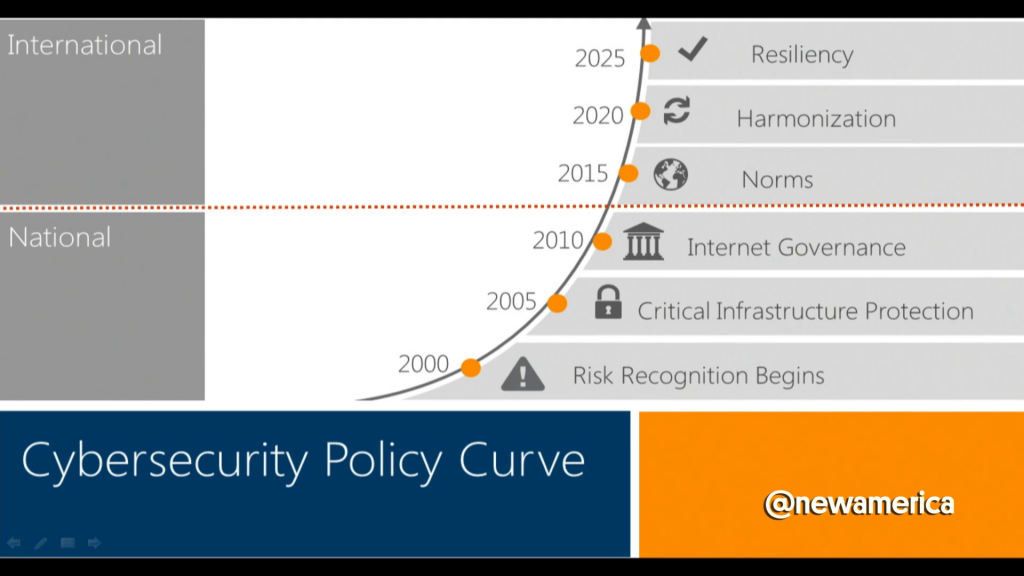

I think it’s important to kind of look at the trajectory that we’ve been on in cyberspace policy. If you go back to the year 2000 and sort of say hey, this is when we started to look at risk, we started to move up from a national perspective and look at critical infrastructure protection. And somewhere between 2010 and 2015, cyber became an international issue. Whether that was tensions around Internet governance. Whether it was around cybersecurity norms and the appropriate role of governments in cyberspace.

And now, more and more our cyber policy is going to be driven by what we do in the international space. What we do for harmonizing these eighty five different laws to ensure that technologies we make can still be exported to the rest of the world? Or that we can consume the latest technologies from other parts of the world? And how together are we going to start to build a more resilient cyberspace, capable of withstanding the next generation of attacks, the next generation of threats, and more importantly a cyberspace that will support and build the next generation of opportunity and inclusion. Thank you very much.