If ten years ago somebody told you that a teenager outside of your house could access your email, banking, and even your personal health information, through flaws in your home’s Internet-connected lighting system you probably think they were watching too much science fiction. Unfortunately, this is becoming a reality in a world that’s increasingly powered by connected sensors. More specifically, connected sensors have three key properties. First, they’re physical objects like appliances. Second, they collect data from the environment around them. And third, they’re connected to the Internet, so they can exchange information with each other, and other systems.

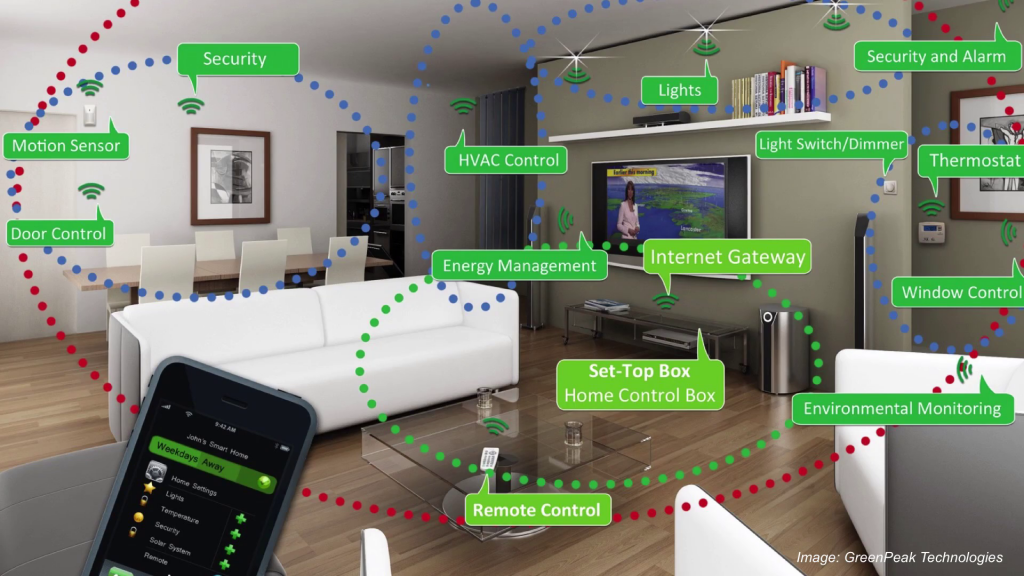

So, these sensors have a wide range of capabilities. Some can see, or record video, others can measure temperature or count the amount of particles in the air. With connectivity, they form a collective that’s greater than the sum of their parts. So when people are talking about the Internet of Things, they’re talking about connected sensors. And as we know, there’s a direct relationship between our reliance on technology and the detriment that can happen if things go wrong.

So for example, we all see the benefits of active safety systems in cars. In this picture, we see an example of a car that avoids accidents by sensing the physical environment around it and then wirelessly exchanging warning messages with other nearby vehicles. But that same safety technology, if attacked, can actually allow you to immobilize a vehicle or even disable breaks while driving.

Image: “Hackers Remotely Kill a Jeep on the Highway—With Me in It” by Andy Greenberg

So, last year there was an example where two security researchers showed how they are able to remotely access dashboard, steering, transmission, and even brakes of a car while it was driving. Chrysler ended up having to issue a major recall which which cost them millions of dollars. And these vulnerabilities affect even our most fundamental infrastructure, like the electric grids that power our cities and fuel our economies. And this ranges all the way from major cities to developing nations.

In this photo, we see an example of how connected sensors can actually help provide electricity in developing regions of rural Haiti. So imagine if the electric grid was attacked. Not only would we lose power in our homes, but water treatment plants would stop functioning, oil refineries wouldn’t be able to produce gasoline, stock markets would grind to a halt. Billions of dollars in damage.

These types of attacks are already at the forefront of cyberterrorism. So the question that we need to ask is why is securing connected sensors any different than securing the computers that we already know and trust for things like online banking and shopping? If we look back at historically how we deal with flaws in security, we often rely on remote updates or patches to fix things after the fact.

Probably the best example would be your smartphone. I’m sure at one point or another you’ve all updated the software on your smartphone. You do it because you think it makes your phone more secure. It’s a good idea. And in fact, your phone is constantly checking for these updates. But what about tiny sensor devices? How can we secure something that may only have enough energy to send a couple of messages per day?

Also, if you think…ten years in the future it’s estimated there’ll be more than fifty different connected sensing devices per person. Who’s going to go around and update all of those different sensors? What happens if those updates fail? There a lot of software developers that are afraid to put in live remote patching for fears that that system in itself would actually add security vulnerabilities.

There’s also the conspicuous nature of these devices. They’re easy to steal because they sit out in the open. They’re harder to notice when they go missing. They’re tricky to configure, because often they don’t have keyboards or displays. And if one of these devices gets infected, it could spread throughout your entire house or your business.

And as is often the case with consumer appliances, the designer of the next big thing, like this Internet-connected toaster, is going to be rushed to ship units and meet deadlines. They’re not going to stop to think about computer security. And even if they do, chances are they’re not going to be computer security experts. And what’s probably most scary is even the very best computer security experts can’t make a system that’s secure forever. Every couple of years we find flaws in our most deeply-rooted encryption standards. There was recently one announced about Android, just a couple days ago. There is in fact one axiom in computer security research that says there’s no such thing as a perfectly secure computing system.

So at Carnegie Mellon University, we’ve been developing and deploying connected sensing technologies for years. We’ve been transforming our campus into a living laboratory so we can experience first-hand both the promise and the perils of connected sensing technologies. So our goal is not only to improve their capabilities in terms of sensing and what they can do for us, but also increase our trust in the technology. We can see that there’s definitely benefit for connected sensors to help streamline our businesses, and improve our lives at home. But what we need to keep in mind is there’s also this balance between risk and reward as we decide which devices should be connected, and perhaps which should stay unplugged.

So I’d like to leave off by asking the question, do the benefits of connected sensors outweigh the risks, and where do we draw the line?

Further Reference

The WiSe (Wireless, Sensing and Embedded Systems) Lab, Anthony’s group at CMU.