Vinay Gupta: So, what I’m going to be talking about today is whether we can get rid of the world’s third-oldest profession, which is bureaucrat. And specifically the bureaucrats that handle resource allocation for our societies. Everybody thinks of bureaucrats as being kind of a neutral force. But I’m going to make the case that bureaucrats are in fact a very strongly negative force, and that automating the bureaucratic functions inside of our society is necessary for further human progress. And this is a fairly audacious kind of a claim, so I’m gonna take it very slowly and we’ll see whether you agree with where I’m going, kind of one step at a time.

I’m also going to talk quite a lot about blockchains and Bitcoin and stuff like this. So I want to start by asking does everybody here know roughly called Bitcoin is? Okay, so most of you’ve got a rough idea of Bitcoin. What about blockchain as some kind of technology which is separate from Bitcoin? Yeah? Okay. So, smart contract? Few people for smart contracts. So I’ll take the technical part fairly gently, and if we get into terrain that nobody understands, please raise your hands, let me know, and I’ll explain the concept. But I’m going to try and make sure that I go slowly enough that all of this comes along because the thesis is radical so the delivery should be conservative.

So, blockchain versus bureaucrat. Four topics that we’re going to cover. What is a blockchain? What is a bureaucrat? What is transparency? And what are our options?

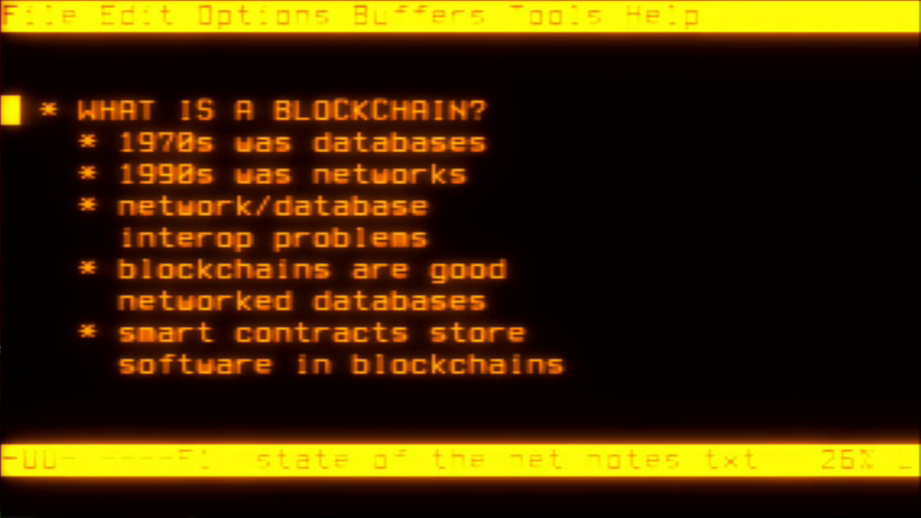

First topic. Basically we’ve gone through roughly forty years of really full-on innovation in software. 1970s, we spent basically twenty years getting everybody’s head around databases. And what it produces is the modern organizational form that we all know and hate, which is the giant silo. And the giant silo runs everything in your society. It’s your healthcare databases, your education databases, your government databases. It’s every company you deal with. Its most scientific research projects. It’s content management systems. You know what this looks like.

1990s, we come along and we spend basically twenty years cranking through what happens when we begin to introduce networks into the mix. So, the Internet gets started. The first access that I have to the Internet is on a machine that has a text-only screen that looks like this, in about ’92 or ’93, using a technology called Usenet, which to this day is still the best information delivery experience I’ve ever had. Because Usenet in those days was only filled with smart people. And it was a text-only medium so people really worked on their language. It’s an amazing medium but very narrow and specific.

The problems that we have in society are largely technology creating economics creating culture. So the problem of databases talking to other databases over the network has never been adequately solved. Every few years there’ll be another generation of proposed solutions—EDI, XML, [WEDI?], SOAP, REST, Ajax, XML-RPC, autonomous agents.

This goes round and round and round and round. It never comes to a real conclusion. Because databases were never made to interoperate. Each database has a model of the world embedded within it and that’s the model of the world of the organization that owns the database. And databases store what that organization considers to be fact.

On the network, everything that you hear on the network is basically hearsay. It’s gossip. And so taking external stuff (which is basically gossip and it’s in somebody else’s world model) into the silo at the heart of your organization is basically much more like getting a brain transplant than it is like learning something. Because our technology is very crude.

So the result of this is that even in a networked society, all of your personal information is in silos. And all of the silos belong to people that won’t talk to each other. So it’s extremely hard for you to make a change in your life and have that change propagate through your environment. When you move house you have to reenter your address in seven and a half thousand different systems. And each one of those organizations probably has 300 copies of your address. And the result is this kind of endless nightmare of human beings inputting the same data over and over and over again into tireless machines, and thus entirely a technological artifact. It doesn’t really kill anybody? So it’s not necessarily important, but it’s a sign of deep, underlying pervasive dysfunction.

So, last ten years or so there’s been another wave of kind of rediscovery of cryptography, largely around this thing called Bitcoin. And the blockchain technology that underlies Bitcoin is simply a database that works like a network, or a network that looks like a database. And Bitcoin takes that concept and builds a single application on top of it which is a currency. And it proves that the technology works. It proves that it can store information securely. Everybody is very happy with it…apart from the people that think that only central banks should be able to issue currency. And you get this enormous kinda Cambrian explosion of expertise in software, because enough people make enough money doing Bitcoin stuff that they can then go off and work on their own projects.

And one project that came about that way is the thing called Ethereum, which implements a thing called a smart contract. And a smart contract is where we take a piece of software and we store it in a blockchain database. So the blockchain ensures that everybody sees the same version of the software. And because computers are predictable, if every single one of us runs the same piece of software in the same environment, we’ll all get the same results. And the result of that is that if you’ve got software inside of a blockchain, and you’ve got a kind of predictable, secure way of running the software, what comes out of this is consensus about what the software does.

So we can take a piece of code. We can all run the piece of code. We can all agree on the conclusion. And as a result we can perform computation that’s done at a societal level rather than with an individual running the computation and then telling you what the results are and asking you to trust them.

So this is a very, very, very early implementation of a kind of kind of genuinely democratic software. Because everybody shares in the computation, everybody shares the result, and you can have confidence across the whole of a society that this is what the software does and this is what the softer says.

And that really hasn’t happened before. The old model is that the software runs in the silo and the people that run the silo tell you what the software says. If the computer says no, that’s the end of the story. In open source software, this is modified a little bit. If the computer says no, at least you could examine the source code and find out why it said no. But you still have all the issues around security and trust about the hardware it runs on and the rest of this kind of stuff.

So the notion that you could have software that runs for the benefit of a society that the entire society can participate in and audit, this is new stuff. And I think that that has gotten obscured a little bit underneath the early press around blockchains and Bitcoin. There is a lot of confusion about what does it all mean and how does it all fit together. But these underlying lessons have become clearer as the stuff grows more mature.

Now, is everybody roughly with me so far? Okay, good. I just wanted to check because this blockchain stuff is really new and really complicated sometimes.

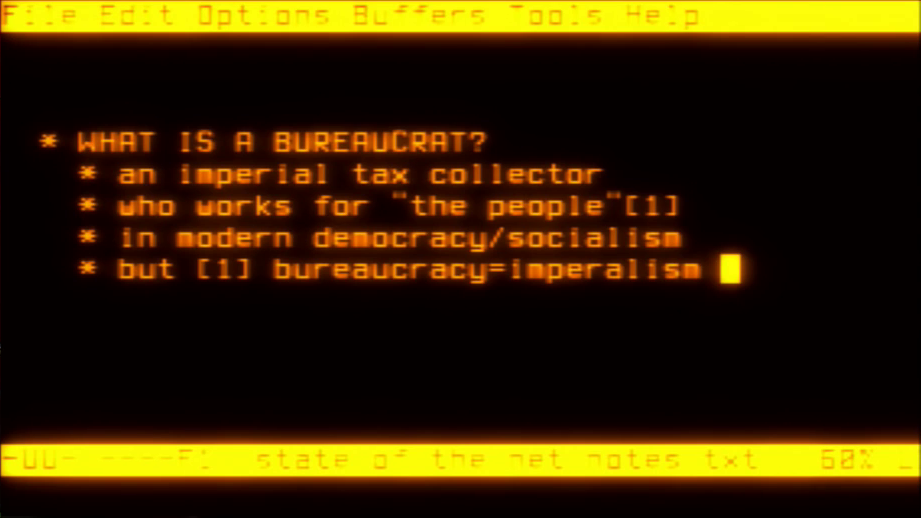

Second topic, what is a bureaucrat?. Would anybody in the audience like to define what a bureaucrat is for me? Yeah, see you’re going to wind up with my definition, which is a bureaucrat is simply an imperial collector of tax. Most of the cultures that have bureaucrats are cultures where the government is funded by taxation. And the job of the bureaucracy is to identify who should pay how much of the tax; who has paid their tax; who has not paid their tax; and who you need to send the boys round to to get the tax off. This is why I say bureaucrat is the world’s third-oldest profession.

In theory, once you’ve got bureaucrats that are working for democracies, the bureaucracy is working for the people as a whole. In practice, if you have an institution which has been imperial tax collection for 4,000 years and then you put a couple hundred years of bureaucracy on top of it, not very much changes. Which is why every time you deal with bureaucrats in central government or in big companies you feel like you’re dealing with an imperial entity rather than with something that represents your interests.

And there is no good bureaucracy, because the organizational form of Hell is the pyramid and every bureaucracy is a pyramid. All that it lacks on top is an emperor, and even that seems to keep coming back. Look at the increasingly imperial machinations of the American presidency, right. This kind of structure in the society never worked for the people, and it was never designed to work for the people. This is an old power structure that we tried to repurpose for democracy and that in fact has never being successfully repurposed for genuinely democratic goals. Reasonable? Maybe.

So once we accept that bureaucracy is the organizational form of Hell and that it defines imperialism, you could begin to understand that there is an incentive for tearing down the bureaucratic structures around us. But we’d like to do that without also taking down the society. Because a post-bureaucratic democracy might be a democracy that actually feels like a democracy, rather than a democracy that feels like imperialism where you get to choose your emperors. This is the hope, anyway.

The agency problem is the kind of technical economics description of this. The bureaucrat always works for the bureaucracy. The broker always works for the brokerage or for their own interest. Finding somebody that represents your interests at any kind of scale larger than the individual is extremely difficult. So if you’re interested in this question of who do the bureaucrats work for, agency problem is where you look for the discussions of that.

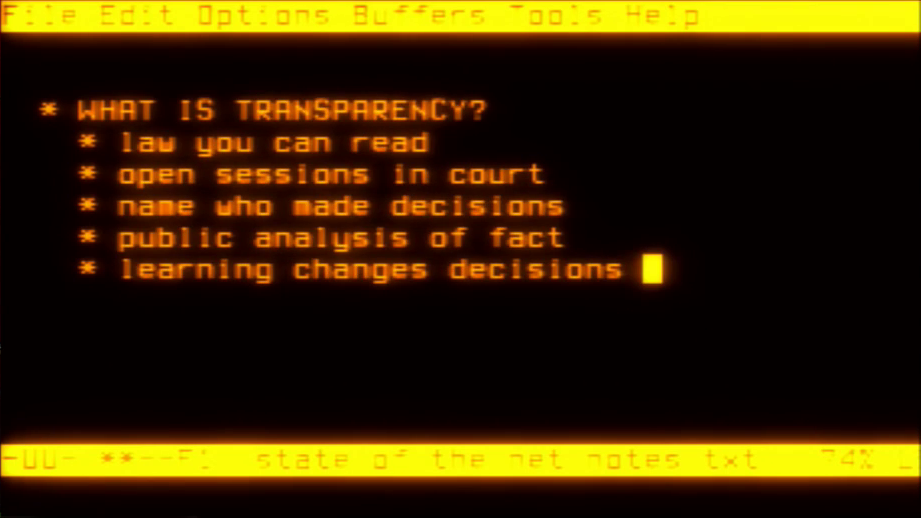

Okay, now transparency. There’s a lot of discussion about things like open data, transparent democratic processes, transparency in government, freedom of information. You know, all these kind of efforts inside a government to be more transparent. But I think that transparency, when you boil it right down, is actually a question of jurisdiction. You can have a certain amount of secrecy inside of government to protect things like a procurement process. But what you want is for the legal processes that oversee the government to be fully transparent. And if you have a transparent legal system, usually it gives you the ability to get the transparency in the other areas where you need it, by force if necessary. You can subpoena information.

So what is transparency? Law you can read. Open courts, where you can actually have people go in and listen to the court making its decisions. The ability to always name who makes a decision. So if you’ve ever worked in a context where you have health insurance, the health insurance people will never take personal responsibility for making a decision. The decision is always the system’s decision, and you cannot extract the name of the individual that made the choice. And in theory this is about protecting these people from reprisals or it’s about corporate responsibility. But in practice it allows you to shuffle somebody who makes terrible decisions at one job into another job without anybody ever having to get fired. The bureaucracy serves the bureaucrats rather than the people that it purports to serve.

The other important part of this is a public discussion about what is true. So, in many cases you wind up in a position where there is no publicly agreed-on definition of true, in the areas where there’s a controversy. And the great mother of all these problems is global warming. But you can also see it around vaccines. America has a recurrence of terrible diseases that we’ve gotten rid of generations ago like, I don’t know, whooping cough, because people have simply started to refuse to vaccinate their children based on a bunch of botched science and a whole bunch of kind of New Age propaganda. And the result of that is a terrible destruction of public safety, caused by what’s essentially a new superstition. It’s like they’ve reinvented witchcraft and they called it vaccination.

So you need some ability in a transparent society to have a general assent about what is true, based on a public examination of the facts, that doesn’t become politically corrupted. And political corruption of science is how this is being attacked right now.

Finally, all of this does no good if you never learn anything. So, when things go wrong you have to have mechanisms inside of the society that don’t repeat the same error endlessly. And usually that means you need some kind of mechanism to draw conclusions like they do for inquiries after an air crash, and then apply those conclusions to the society that you’re operating in. So you don’t repeat, you always have some kind of accountability so that when things go wrong you can point the way.

My suggestion is that blockchain technology, particularly smart contract—so software in blockchains—has all of the attributes necessary to provide transparent governance. You can have a piece of software. It’s stored in public. Your decision-making processes is inside of the software are completely transparent. The people that put the software into the system are named individuals and the audit processes are also all done on a blockchain. The public analysis of fact is in the form of a thing called an oracle, which is where you take information that is not intrinsically inside of a computer like temperature of the ocean, and you agree on the fact before it’s placed into the software. And then finally the outputs are all visible, so it’s possible to go over the entire set of outputs of the system and look for what actually happened.

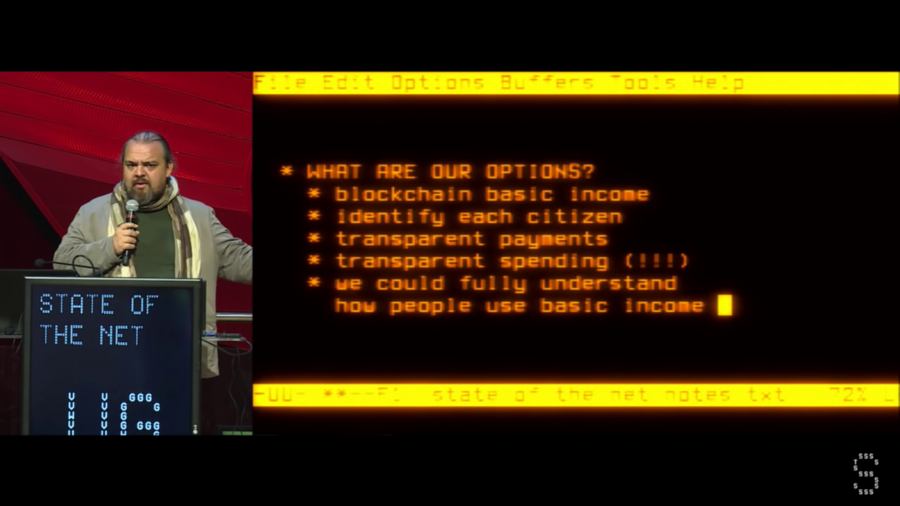

So if we have software that can implement transparent governance, the question then is what can we do with it? And I have a kind of radical suggestion, which is really just something to play with. But I think it gives some scope of the new possibilities. And if you could do this specific instance there must be 800 other things you can do which are smaller, easier to implement, or less controversial.

So, my suggestion is this: We could implement basic income on a blockchain. You could take a small society, or even a big society, and you could decide that every citizen will have so many tokens which are issued to them every day or every month or every year by virtue of their citizenship. And you could say that these are euros, but this creates a problem of financing these things. So you could suggest that you’re going to use some kind of electronic currency.

So you have a basic income unit which is issued into the society, in known scarce quantities. And what that unit is worth is allowed to float on the market and becomes worth whatever people decide it’s worth. And you can increase or decrease the amount issued, depending on social policy decisions.

Blockchains are ideal for this. You want to identify every citizen that’s entitled to payments: you log them into the blockchain systems. You want the payment to be transparent: the software issues the payment and everyone can see what the payment was. There’s no ambiguity in this. Because everybody is known to be receiving exactly the same size of payment, there’s no social stigma associated with the payment. So having it be fully transparent might have less of a negative impact than you would get if it was say a means-tested benefit. And I think that is a—you know, it’s a jump, but I really wanted to show something which is a little sci-fi, just to see what we think.

The outcome of this is that you get transparent spending. So, because all the spending is done on a blockchain, you can see what the stuff is spent on. And at this point you have a decision to make. You can require that citizens are identified on the blockchain by their name, or you can protect their name and have them identified on the blockchain by a pseudonym, or an alias, or a randomized identity number.

So, in one of these paths you get complete transparency about individual spending, and in the other path you only get transparency about the general aggregate of spending. And then there are questions about can people be deanonymized successfully. The answer to that is it depends. It’s a complex technical question. But generally this is one of these social choice decisions where you’ve got to decide whether you want full transparency or not.

With a transparent spending database, you could then do really detailed analysis of how the money from basic income is being used. And I think everybody involved in the basic income debate, whether they’re for it or against it, could agree that basic income is a really good thing to get complete knowledge about.

So you take this new technology which is kind of untested at a large scale. (Blockchains.) You take a set of requirements for a system to be transparent and implement a blockchain technology that is faithful to those. Which is pretty much all of them but you want to be clear. You need a much more detailed specification than the one that I’ve outlined. And then you take a new social policy instrument like basic income and you implement it on top of the blockchain to give you a laboratory in which you can see exactly what’s happening inside of a social innovation, to decide whether or not you want to scale it, whether you want to continue it, just to understand what it is.

And I think that there’s an enormous amount of room for taking problematic areas of society and deploying these kind of lens solutions to them. We’re going take this problem. We’re going to implement a solution that we can monitor every single aspect of. We’re going to run it on an experimental basis. And we’re going to agree all the way through what the rules of the game were, to make sure that people aren’t cheating in some way to make the idea look like a better idea than it is.

The software can be audited by all parties before you put it into the system. And in this instance the code literally is the law. There’s no distinction between who implements the software and who makes the law. The law and the code are one. So you need to have a legal process by which the authority of the state or the authority of a corporation or a sort of charity, even, is transferred directly into a piece of software. And those mechanisms already exist. You can get there through binding arbitration. You can get there through what’s called Ricardian contract, designed by a friend of mine called Ian Grigg. There are lots of approaches to that problem but you just need to pick one and implement it.

Does this generally sound…even slightly possible? Yeah, right? So I sort of sat down as I was writing the slides for this thinking, can it really be that easy? Is it even remotely reasonable that you could just come along and take a bunch of new social policy; write a bunch of software; put the software into the new social policy; and then do the analysis in real time as the transactions were done?

And I kept looking at it like that can’t be right. There must be some catch. It must be anti-democratic, or blatantly illegal, or it must give you corrupted data or something. And I kept looking at it and I couldn’t figure out why it wasn’t a reasonable thing to suggest. So here we are talking about it. And if anybody can tell me why it’s not reasonable, let me know. Come up and tell me afterwards or talk about it on Twitter.

Because as far as I can tell, it means that you could try basic income at a whole of society level with very little risk and very little cost. And you could monitor exactly what was happening. And given that half of Europe has an enormous problem with access to liquidity, it seems like you could have an injection of liquidity into the societies without necessarily causing mainstream economic disruption. And if it doesn’t work it’s fairly easy to turn off. It was quite surprising.

Now. What this kind of suggests is a method of government innovating. Because right now we’re in a position where governments have ceased to innovate. In fact, they’re all living inside of this bizarre fantasy world which is left over essentially from the end of World War II. The state hasn’t really gotten to grips with modernity in any fundamental way. Anytime you have a decision being made, the basic structure and process that makes that decision is the same structure and process they would’ve used after World War II. Things are a bit different pre World War II—there’s much more diversity in how governments operate. After World War II there’s a strong consensus. It comes out this is pretty much how a state should be run, and we kinda fall into this pattern.

The problem is that that pattern is very very poorly suited to exactly the kind of complex modernity that David Orban was talking about, all of this kind of strategy up exponential curves business. You know, rapid rate of change plus 400 year-old democratic design, plus bureaucracies that date back to World War II, gives you this problem where the rate of change of the world massively exceeds the rate of change for democracy to be able to adapt to the world.

And the result is an increasing transfer of power from democratic to non-democratic institutions. The only reason that the corporations wind up with such enormous power is because the government is unable to solve problems without them, and basically lets them run around doing whatever they like the rest of the time.

So, because the corporate forms can evolve rapidly, because you’ve actual competition between forms, there’s this continual push and this continual acceleration. And what it produces is a much better understanding of how to deliver change than you get if you’re inside of a bureaucracy where your boss changes every four years, using a procedure that’s 400 years old, and the institution does quarterly reporting but really only measured on a four-year cycle for elections. You see this kind of mismatch of speeds, right. It’s a problem of tempo.

So if we could develop mechanisms for weaving the existing superstructure of democracy in place, but performing experiments inside of transparent subsystems, it’s possible that you could use blockchains and similar technologies to build experiments at small scale with the mandated authority of the state but without going through corporations as the implementers.

So, open source software commissioned by a government, built by a university, deployed across a population with a social mandate behind it, gives you a kind of test pool for new concepts that can be tried in an environment where nobody can accuse anybody of hiding cards up their sleeve.

And that sort of notion that we’re lacking, that ability to test new ideas in society, is behind a lot of the crazy thinking that comes out of Silicon Valley. So the seasteading movement by Patri Friedman (or rather Patri Friedman ran initially) was this idea that you could build kind of little artificial islands out in the oceans. You could stick a flag in them and declare they were sovereign. And then you could experiment with new forms of government. This one will have an election every fifteen minutes and your phone will do artificially intelligent voting for you. This one over here will have six-person MP groups rather than individual MPs, and they’ll rotate off the job. This one over here will randomly select who the MPs are, and they’ll have a tenure which is decided randomly. This one over here, you’ll just have sortition every four years, you’ll randomly select… You know, all of these kind of different approaches could be tried in these kind of microcosms, and we could potentially find something that works better than four or five-year electoral democracy.

But, the problem with this is the assumption that you need to be able to take territory, have sovereignty, get land and all the rest of this, makes it incredibly difficult to get these kind of experiments in governance going. And, who watches the watchmen? What do you do when one of these things turns into a total disaster? Are these people going to then go back to their original nation-states and beg for help? You know, you can imagine these projects if they go down, the humanitarian fallout could be quite substantial because you’d have a crash of governance in a tiny little island society. And I don’t like the smell of that at all. I mean, I’m quite… I’d love to see the experiment tried, but I think it’s quite risky. And we certainly can’t solve problems quickly if we have to establish a new nation-state every time we want to try an experiment.

So what I quite like is this idea that we could do lots of experimental stuff inside of the body of democracy by using transparency technology to de-risk experiments in government. And the notion that these blockchain technologies are a fundamental transparency breakthrough, and that you can push forward with that set of schemes to try these experiments in all kinds of different places and for all kinds of different things, with the ability to document exactly what happened for future generations, seems like a really sound and sensible way to do experiments in governance.

And you don’t really hear “experimental governance” all that often. But it’s clear that we need it, because the existing systems don’t work—we all know that. I mean, does anybody live in a country where they feel like their government really works? I went to Singapore. Their government really works. I mean it’s incredibly efficient. But they basically run the entire island like a single corporation. And private enterprise complains that they can’t get enough talent into private companies because all the smart people work for the government and they just hire them right out of university and give them a job for life. And it seems very unlikely that we’re going to succeed in changing our societies in that way, and we probably wouldn’t like it even if we did.

So we have to get better at learning inside of democracy. And my suggestion is that blockchain technology is an inherently useful part of learning inside of democracies. It came from the libertarians. It was dressed up in some very weird clothes when it arrived. But if you get a good solid chance to look at it and talk to it and get some sense of what’s going on under the hood, I think it’s pretty clear that it’s simply about transparency. And transparency is a methodology that can be pulled out of any political setting and reapplied everywhere else. Because the truth is only one, right. When you get right down to the fundamentals, a transparent system is the same for everybody that uses it, and there’s no reason that that should be identified with libertarian or any other kind of politics. It’s something that people of any political persuasion can apply.

So that’s the basic thesis. I think that blockchains are good for democracy. And I think that if we use them wisely inside of government, it will give us an opportunity to do social experimentation in governance—in fact, just experimental governance—in a way that is largely de-risked and politically neutral because of the transparency aspect. I will also go on to some kind of subtopics after this, but that is the main talk. Thank you.