So what is afrofuturism? Afrofuturism is really about the black body and the black mind seeing itself put into a space that is beyond the white supremacist structure that we’re currently in at the moment. It’s placing ourselves outside, into a paradigm of futurism, afrofuturism.

The term was invented by Mark Dery in 1993 in his essay “Black to the Future.” In that essay he wrote,

Speculative fiction that treats African-American themes and addresses African-American concerns in the context of 20th century technoculture — and, more generally, African-American signification that appropriates images of technology and a prosthetically enhanced future — might, for want of a better term, be called Afrofuturism.

Mark Dery, “Black to the Future,” 1993

The first slide I’ve got up here is of Sun Ra. Some of you might know, some of you might not know, but Sun Ra is probably one of the pillars of afrofuturism, and it works across different genres. So we’re talking film, media, music, and literature, the main two being music and literature, I would say. Just to get us into a kind of afrofuturist vibe, mood, and get us out of this kind of square, Westernized room, I’m going to play a short clip from Sun Ra’s Space is the Place to put us into that vibe, and then we can continue on to the African space program.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9NJ2oXwWEvw

In that imagery, you can see a lot of African cosmology, Egyptian cosmology, and these idea of ancestral worship, bringing those into an opposition to the colonialized mind, I guess, which is the Christian white supremacist mind that was imposed on African slaves. There’s a lot of things around afrofuturism connecting through ancestral worship, which I’ll touch on again later.

But talking about literature, Samuel R. Delany is a queer African-American science fiction writer (probably one of the most famous besides Octavia Butler), and he said about science fiction,

Science fiction isn’t just thinking about the world out there. It’s also thinking about how that world might be—a particularly important exercise for those who are oppressed, because if they’re going to change the world we live in, they—and all of us—have to be able to think about a world that works differently.

Samuel R. Delany, “The Art of Fiction No. 2010”, The Paris Review

And some of the other writers that are working around those issues are Nalo Hopkinson, I already said Octavia Butler…I’ve got that stage fear, so you’ll have to come speak to me later when I’m on the panel and I’ll probably reel off about ten by that point.

The next slide’s for those who are oppressed, and how we create images outside of that oppression for ourselves as afrofuturists, as black artists, as black comic book artists.

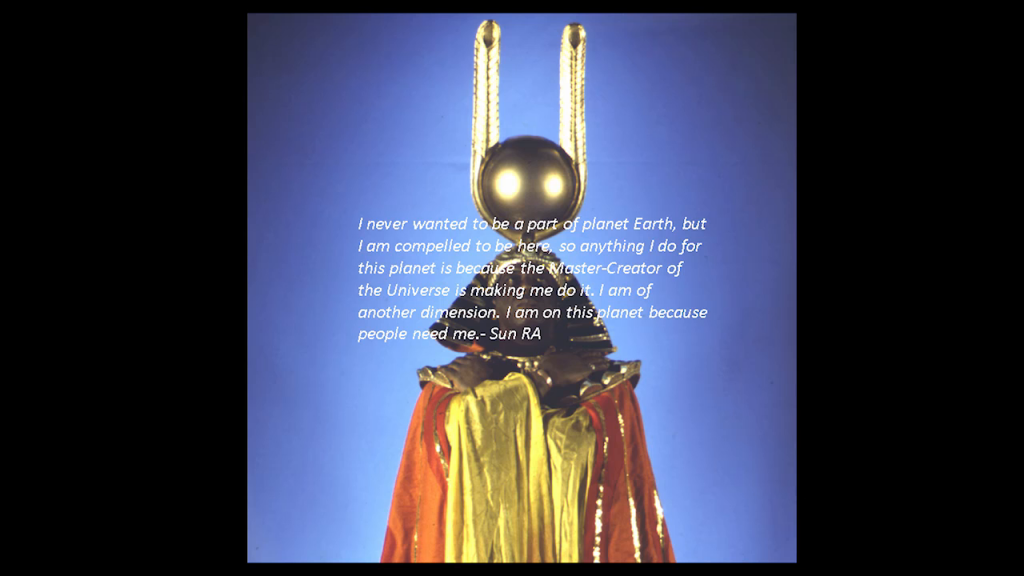

Some artists who are working around comic books are people like one of my favorite comics at the moment, Jiba Anderson’s Horsemen, which is a comic series placed around Yoruba gods and goddesses. The Yoruba gods and goddesses are part of Nigerian Orisha culture, and they are Ṣàngó, Yemọja, Ọ̀ṣun, Ọbàtálá as well, and when the slaves were taken to places like the Caribbean and Cuba, they synthesized their religions with the Catholic religion, which is the religion I was brought up in.

What happened is that you ended up with this mix of mysticism, Catholicism, and people using those gods as cover-ups, essentially, for the African gods. This is reflected in the Horsemen comics, so you have these characters and then behind them they all represent different gods and goddesses of Yoruba culture.

There is Kamau Mshale, the creator of the comic Captain Kachela which uses and Adinke and Akan symbols, which are from Ghana. And Denenge Akpem, who recreated her own water fairy tale which is reminiscent of African mermaids by transforming herself into a space sea siren hybrid jellyfish…thing. A lot of hybrids going on there. And many artists reference the Dogon people, which I will touch on a bit later, who believe their ancestors arrived on a flying arc from a distant star.

So that’s literature, that’s comics, there’s also visual artists as well, which I’m not going to touch upon today. But going back into music, which for me as a DJ and a musician is probably one of the main things to do with afrofuturism that I work around, and also around digital histories. There’s a piece by Daniel Kreiss who’s written about how Sun Ra and the Black Panthers appropriate technology and the piece is called “Appropriating the Master’s Tools.” I don’t know if anyone’s familiar with the black feminist writer Audrey Lorde; she has this famous quote which is “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” It’s about creating our owns, those of the African diaspora, to dismantled institutions like this. It’s a lovely room, but it’s very representative, there’s dead white men on the walls, so we can’t dismantle those structures by recreating it with dead black men, for example. We need to completely dismantle the gender binary, patriarchy, and all that kind of stuff.

So Daniel Kreiss writes,

In 1952 jazz musician Sun Ra began using metaphors of cold war technologies in his performances in an effort to create a technologically-empowered mythic consciousness for black people that he imagined would enable them to control technologies and build the societies of the future. Through his music Sun Ra constructed and performed what I call a ‘black knowledge society,’ a metaphorical utopia of consciousness facilitated by science and technology and grounded in the cultural values of ancient Egypt and a re-imagining of outer space. Sun Ra’s engagement with artifacts and metaphors of energy, outer space, and advanced technologies

represents a black cultural uptake and reconception of cold war science in terms of long-established African-American social narratives of liberation and empowerment.Sun Ra felt that African Americans were going to be left behind as the technology changed around them unless they developed the technical agency to both use and reinvent the tools of white society. For Sun Ra, this agency could be established through the creation of a mythic consciousness for black people that was centered on the metaphor of a ‘black knowledge society’ informed by the cultural imagining of Egypt and outer space.

Daniel Kreiss, “Appropriating the Master’s Tools: Sun Ra, the Black Panthers, and Black Consciousness, 1952–1973”

Outer space and how that forms itself in “afrofuturist music.” I say “afrofuturist music” because that music works across different genres, it works across Sun Ra from jazz to George Clinton to Janelle Monáe to Outkast, and a wealth of others.

Let’s go to George Clinton, who I actually DJ’d for five years ago I think. It’s quite an interesting story so I’m going tell it because it’s wacky. It’s like a science fiction novel. I was in the back and it was a European festival so we’re all being very European and quite staid. Then two or three of these massive big silver trucks came backstage and then the doors opened and some girls came out on roller skates. Smoke came out, and then there was these troops and then there was more roller skates. And then he came out with around ten people around him. I play in a punk band and this was one of the loudest shows I’ve ever been to or played. It was painful. He had people doing all kinds of stuff. It was like entering a mothership of some sort.

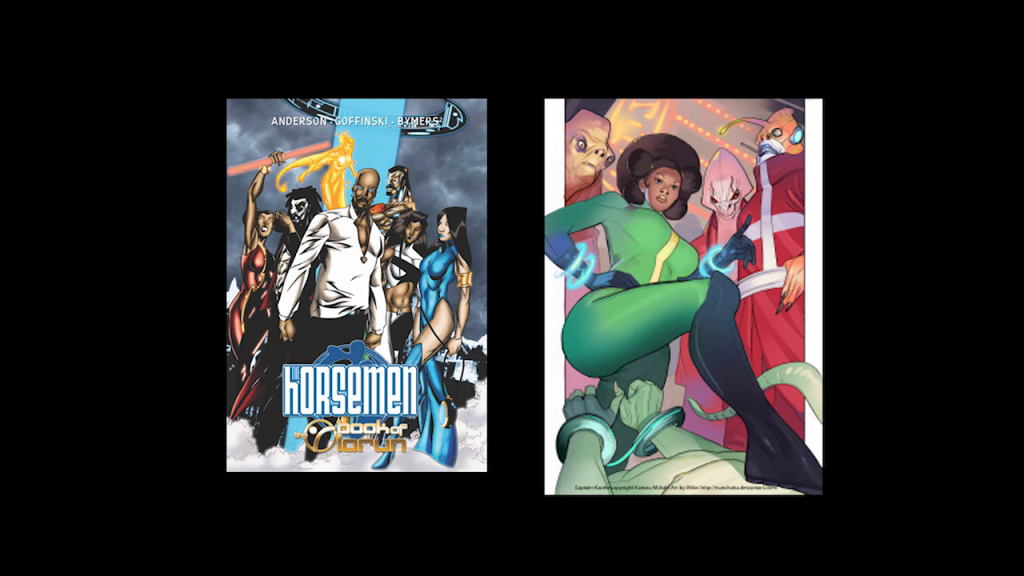

But George Clinton’s groups Parliament and Funkadelic. Parliament had more constructed stories, they had the whole mythology of P‑Funk, which I’ll talk about a little bit in a minute. And Funkadelic leaned more to the ethereal and the spiritual, which is probably more reflective of them in that era of the late 60s when Funkadelic came around. So it’s Funkadelic, then Parliament came after.

So the Mothership Connection, which is the name of my book club. Why did I call it Mothership Connection? Obviously a big fan of George Clinton, but it’s also that thing of how this idea of us as African diaspora-displaced people living in alienating society, this idea of being from somewhere else kind of fits in with aliens and spaceships. So the Mothership Connection, even though it’s a flying saucer, it really is about this idea of connecting back to African epistemologies, African ways of thinking, being, seeing the world.

When I wrote my piece for The Guardian, there was a big row in the Guardian comments, as there always is. Someone had said that George Clinton and Parliament weren’t political, because I’d mentioned this thing about them bringing this political edge into their music. There’s a quote from this spiritual song “Swing Down Chariot” that George Clinton uses in this song. It’s an old spiritual chant, and it’s that chant that slaves used to use while working. “Swing down sweet chariot / Stop and let me ride.” There’s all these references that he puts into the music which is about escape, which is about redemption and liberation, etc.

On the Mothership Connection, Starchild (which is George in another form; he has all these different identities as well) is a divine alien being who comes to Earth from a spaceship to bring the Holy Funk, with a capital F not a small f, the cause of creation and source of energy in all life to humanity. As it turns out, Starchild secretly worked for Dr. Funkenstein, the intergalactic master of outer-space funk who’s capable of fixing all of man’s ills because “the bigger the headace the bigger the pill” and he’s the big pill. Dr. Funkenstein’s predecessors had encoded the secrets of funk in the pyramids (again, a lot of references to ancient Egypt) because humanity wasn’t ready for its existence until the modern era. Those of you who are into hip-hop as well can see the connections there with Afrika Bambaataa and “Planet Rock” and all that kind of stuff as well.

So music and technology from Sun Ra, cold war technologies, George Clinton was doing a lot of innovative stuff at the time particularly in stage shows and production. One of the music groups that comes up a lot in afrofuturism is Drexciya. Drexciya are from Detroit. They are two black guys, no one’s really sure what they look like because they’re always wearing masks when they perform. And there’s always this theme with black music culture of using the latest tools. We see it in grime, we see it in house music, we see it in a lot of things. With Drexciya it’s techno. I’m just going to play a little bit here. It’s a bit heavy. It might be a bit much for this time in the afternoon unless everyone wants to have a bit of a rave. [Plays ~20secs of the following.]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=imKh_TKqHt4

What’s interesting about Drexciya is at the time they’re using this technology which is quite forward in music, but they’re also bringing in a philosophy that underpins all of their work. They’re putting together disparate strands of afrofuturism, political activism, and Platonic philosophy. The duo formed the detailed mythology of the Drexciyan people, who were an aquatic race descended from the children of pregnant slaves thrown overboard during the Atlantic crossing. The music they produced were messages from the Drexciyan race (this song is called “Wavejumper”), creating a portal between Africa, contemporary America, and the depths of the Atlantic Ocean, and as the myths developed, so did the music.

So as I was dancing on the stage for you guys here and talking about the looping of house music, that sort of 4/4 time which comes directly from a lot of African rhythms, I’m going to play a bit of the sacred drums of Burundi. You’ll see that the effect of this music is not very far from the effect caused by techno or electronic music, as these musical styles both work on the concept of loops. Whilst thinking about this, it’s quite interesting to think about shamanism, and [as] this is Haunted Machines we’re talking about magic, and going into these magical spaces. Shamanism is used colloquially as a blanket term to describe traditional tribal religions not stemming from Abrahamic faiths.

So thinking about Drexciya and the mythology that they’re creating around the Drexciyan people and then the Burundi sacred drums and then if you’re in a rave and listening to that music and you’re being taken off into that space, it is effectively black music, this sort shamanic thing that dance music has. I’m going to play a little bit here and I think you can get a sense of what I’m talking about.

https://youtu.be/74EoeEUwhoI?t=274

There’s always this thing about the circle as well, of keeping a loop going rather than in a lot of Western music which is very forwards in a march.

I’m now going to talk a little bit about technology is black political resistance and as black liberation. As we live in the age of the Internet and this is the FutureEverything festival, I’m going talk about things that are happening now, things of people that I communicate with online and black online culture, black liberation culture.

Colin [?] wrote a piece, and in it he quotes,

Throughout the black diaspora, the phrase “knowledge is power” has been a cultural tenet used by many communities of African descent in the attempt to liberate themselves from the oppressive throes of racism. The collection, storage, and dissemination of information about how racism works in their communities, what groups and resources are available to combat racism, and what historically has been done, continue to be a valuable weapon in our liberation struggle.

So I was talking about having a conversation with someone recently, and we were talking about science fiction by black writers and science fiction by white writers. They said to me, Have you noticed that a lot of black science fiction is actually…I won’t go as far as saying utopian, but doesn’t have a relationship with technology which is as negative sometimes? There isn’t that dystopian sort of “technology is going to be the end of us all, we’re all going to end up like Borgs” and all that kind of stuff. A lot of it is about technology liberating us from certain spaces.

Black Girls Code is a group that started in the West Coast of America, and its mission is to introduce programming and technology to a new generation of coders, coders who will become builders of technological innovation and of their own future. They usually work with young girls between the ages of 12 and 16, and they teach these girls how to code because there’s obviously a lack of black women particularly in that industry. This idea of being the forward change, knowledge is power, that sort of thing.

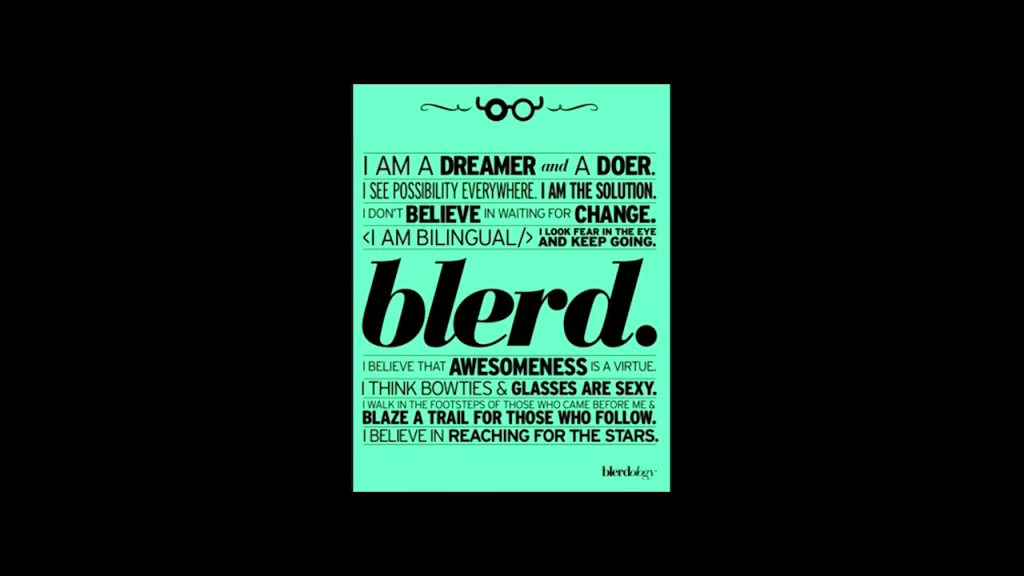

And blerd culture, which is another thing that’s kind of sprung up online, black nerds—blerds. We always put a “b” in from of everything. We’ve got the blipster which is the black hipster, now we’ve got the blerd which is the black nerd. And when did this start to spring up? Maybe four, five years ago I started to notice the term pop up around the Internet through hashtags for a lot of stuff around black science fiction that I was talking about. And what does it say on the poster?

I am a dreamer and a doer. I see possibility everywhere. I am the solution. I don’t believe in waiting for change. I am bilingual. [Chardine: Which seems an odd thing to say.] I look fear in the eye and keep going. I believe that awesomeness is a virtue. I think bowties & glasses are sexy. I walk in the footsteps of those who came before me & blaze a trail for those who follow. I believe in reaching for the stars.

What I’ve noticed about blerd culture is this thing about defying typical black stereotypes of music lovers (I say that thinking about myself.) and bringing people into technology, and making something that black people can participate in. That is happening a lot online.

The power of Black Twitter and hashtags, Black Lives Matter, which is a campaign that I sometimes work with. There’s been some studies looking at how black people use Twitter. It’s actually slightly different from our white counterparts. 26% of African-Americans who use the Internet use Twitter, compared to 14% of online white non-Hispanic Americans. In addition, 11% of African-American Twitter users say they tweet at least once a day, compared to 3% of white users. In 2010 there was an article by Farhad Manjoo in Slate magazine, “How Black People Use Twitter”, which brought the community wider attention. He wrote that

[Y]oung black people—do seem to use Twitter differently from everyone else on the service. They form tighter clusters on the network—they follow one another more readily, they retweet each other more often, and more of their posts are @-replies—posts directed at other users. It’s this behavior, intentional or not, that gives black people—and in particular, black teenagers—the means to dominate the conversation on Twitter.

Farhad Manjoo, “How Black People Use Twitter”

He goes on to argue that the higher level of reciprocity between the hundreds of users who initiate hashtags, or “blacktags,” leads to a higher-density influential network. I don’t know if anyone’s ever engaged with Black Twitter here, or been on the receiving end of Black Twitter, but it’s a force to be reckoned with online. I engage with it quite a lot, like some of the #BlackLivesMatter campaign. You see how Black Lives Matter started as a hashtag and then became a movement afterwards. Now it’s an organization, and I do a lot with Patrisse [Cullors], who heads that organization, actually. So black people connecting with each other and creating a voice in a digital space as well. If you don’t have a space in somewhere like this, you can create a voice in a digital space, which is what’s happening with the hashtag.

There’s a Kenyan film director, Wanuri Kahiu, who made a 20-minute short film called Pumzi which is set in the future and you see use of technology to [sustain water], which is obviously quite a big issue in certain parts of the continent at the moment. I really recommend it. It’s a really beautiful film. Wanuri talks a lot about afrofuturism as well in a particularly African context, not the African diaspora context. In terms of modern afrofuturist thought, her work is really progressing that forward.

I talked about the Dogon people and space [and] Sirius B. The Dogon people are from Mali in West Africa. They’re believed to be of Egyptian descent and their astronomical lore goes back thousands of years to 3,200 BC. According to their traditions, the star Sirius has a companion star which is invisible to the human eye. This companion star has a 50-year orbit around the visible Sirius and is extremely heavy. It also rotates on an axis. That’s all the technical stuff, but the most interesting thing about this is that the stories that they are telling at that time were effectively real. Those planets weren’t discovered until we had telescopes and things like that here. So again a lot of afrofuturism refers back to this story because it’s about ancestors, myth, modern technology, and this idea of time and space in African ways of thinking being circular, being led by events rather than by dates.

I’m going to end on an artist called Ras G because I’m a DJ, so that’s what I do. I’m going to play music, because it’s quite important to me. And this sort of modern musical afrofuturist movement with groups like THEESatisfaction and Shabazz Palaces. I’d also recommend if people are interested in looking into this further, to have a look at web sites like OkayAfrica, Chimurenga magazine, which is a zine coming from South Africa which talks afrofuturism as well.

So I’m going to end on this. It’s called Ghetto Sci-Fi by Ras G & The Afrikan Space Program.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7MN7pkfMnMs

Further Reference

Dedicated page for Haunted Machines at the main FutureEverything site.