Forgive me, I actually have to read my text. So, celebrity chefs. There’ve always been celebrity chefs whose skill and creativity made them famous. But the passage of time usually means we know little more about them than their names. From ancient Greece and Rome there’s only one cookbook that survives in full, that attributed to the Roman cook Apicius, which dates actually from the end of the Roman Empire.

I’m going to talk about the Western world, but I should point out that there were famous chefs in many places and periods, notably in the spectacular gastronomic cultures of the Islamic Caliphate of Baghdad; the Ottoman Empire; and Tang, Song, and Ming China.

But to begin with the Greeks. A chef named Miticus of Syracuse is mentioned by Plato. And according to the Sophist Maximus of Tyre, Miticus was as great in the art of cookery as Phidias in sculpture. And since Phidias was the most famous sculptor of the ancient world, this is high praise indeed. Yet we have only one recipe attributed to Miticus, that we know of, and I’ll read it to you because it’s really short.

How to make ribbon fish

- Cut off the head of a ribbon fish.

- Wash and cut in slices.

- Pour cheese and oil over it, and cook.

So this is a little disappointing. We’re told by Athenaeus, the most accomplished gourmand of the classical world, that a certain Glaucus of Locri invented an excellent sauce called hysophagma. But we have no other information about this guy. Athenaeus says that the sauce was made with fried blood, honey, milk, cheese, herbs, and silphium. Silphium was a sharp and sour-tasting plant that grew in North Africa, a favorite condiment of the ancient world. And I put this in the past tense because it became extinct. It was so sought after. Legend has it that the Roman Emperor Nero publicly consumed the last silphium ever foraged.

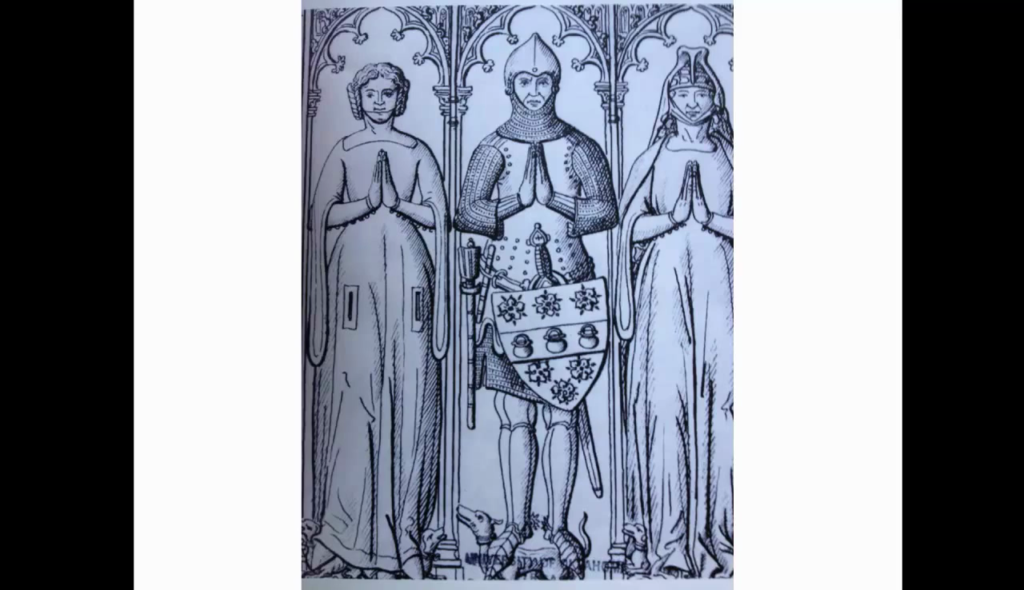

The first renowned chef in the Western world whose life we know something about is Guillaume Tirel, known as Taillevent, who lived from about 1310 to 1395. He was chef to two kings of France, and he qualifies as an undoubted celebrity. King Charles V bestowed on him a knighthood and a coat of arms, here depicted from his brass tomb cover. And on this tomb, Taillevent is dressed as a knight. In armor and a sword, flanked by his first and second wife. Not simultaneously; one died. Notice the dog at his feet and at the feet of the wife on his left.

You can see that his coat of arms consists of two groups of three roses top and bottom, with three stew pots along the center of the field. As symbols of chivalry, the pots may seem to imply contempt or amusement, but they remind the viewer that the chef was honored for his craft. At any rate, Taillevent, who designed his own tombstone, was quite pleased with this heraldic device.

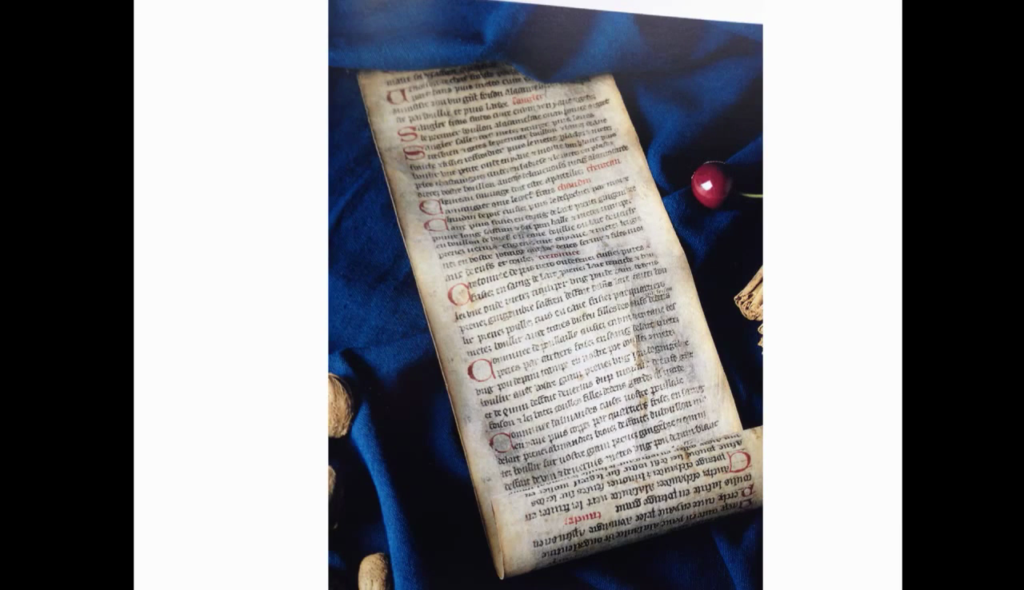

Taillevent was part author of a medieval cookbook known as The Viandier, which consisted of recipes from before Taillevent was born but to which he seems to have added. The oldest version of The Viandier is this 15th-century parchment scroll in the Cantonal Library of the Valais in Sion, Switzerland. And there were over 150 cookbook manuscripts from the 13th through 15th century, many of them still unedited.

Nothing is further from reality than the Hollywood image of crude medieval dining in films such as Becket… Well, any number of films, where haunches of roasted meat are torn apart without regard for manners or ceremony. In fact, medieval cuisine was complicated, piquant, subtle, and served according to very elaborate rules. So for example, there are several medieval handbooks of carving—just of carving instructions—one of which from England in the 15th century is so finicky that it matches particular verbs to each cut-up fish or animal. So you unbrace a mallard, but you tranche a sturgeon. You dismember a heron, but you tame a crab. And if you make a mistake in this terminology you’ve shown your ignorance. All authorities agree, by the way, that crab is the hardest. According to an experienced household manager named John Russell writing in the 16th century, “crab is a slut to carve.”

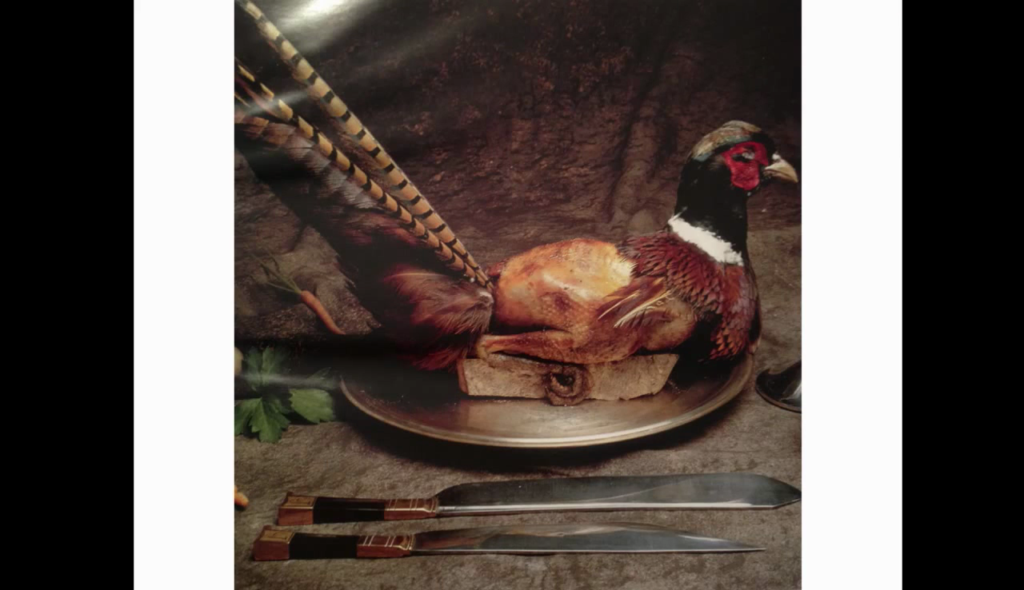

Medieval chefs loved trompe l’oeil. Meatballs glazed with parsley sauce to look like green apples, or cooked animals that appear to be alive, as with this pheasant made according to a recipe of Taillevent in which the feathers and skin are carefully sewn back on to the roasted bird.

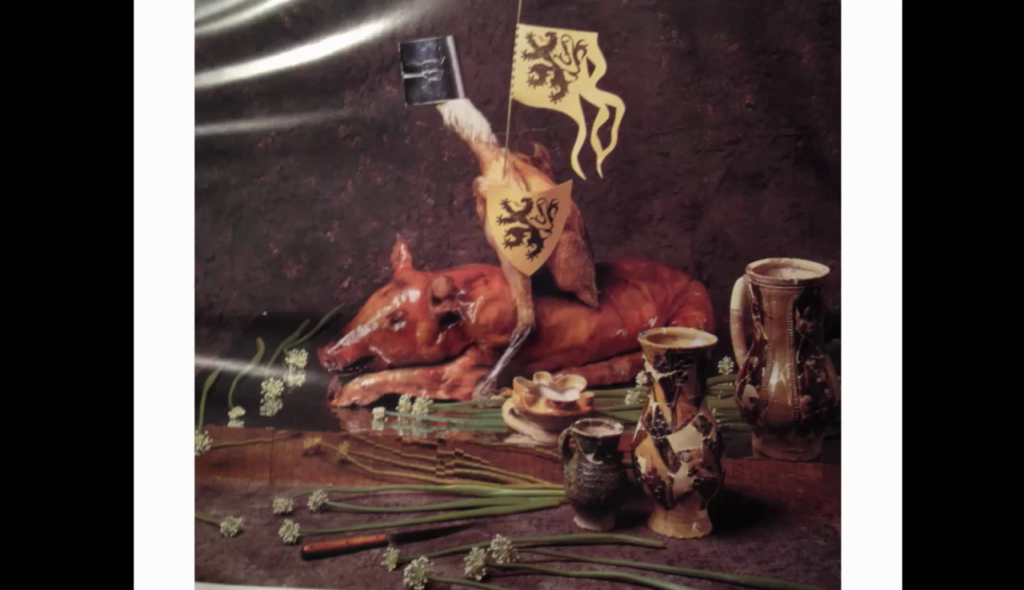

They also had a ponderous sense of humor. Here is another dish of Taillevent’s called coq helmet (helmeted rooster) in which the rooster is mounted on a glazed suckling pig.

The renowned chefs of the Middle Ages, Renaissance, and Baroque eras were in the employ of great nobleman or princes. And they put on amazing banquets. And we have very few records of them worrying about any sort of financial bottom line. That doesn’t mean they [were] free of stress. François Vatel committed suicide when the fish failed to arrive at Chantilly for a banquet celebrating a visit from King Louis XIV. But actually, he was not a chef as much as a household official in the Prince du Condé. He had some other problems as well. But his fate has become a legend emblematic of the pressures under which chefs operate. And you all know, I think, the tragic suicide of Bernard Loiseau in 2003, caused supposedly by his apprehension that the Guide Michelin would take away his three star ranking.

Chefs of this era also had to put up with annoying interventions from their employers. This painting in the Albright Knox gallery in Buffalo, New York is entitled “The Marvelous Sauce,” by a painter named Jehan George Vibert. And it shows a cardinal instructing his dubious and harassed-looking chef in how to make a sauce.

All of these irritations notwithstanding, there was a lot of fun and excitement. Just random example of many possibilities, a rather modest dinner served in 1524, during Lent, to twenty-four guests at the court of the Duke of Ferrara in Italy included three courses, each with forty five dishes. Thirty of them, the first two courses, were made with sturgeon. The head cooked in white sauce with pomegranate seeds. Sturgeon meatballs in sauce, served on bread. Sturgeon slices in pistachio sauce. Sturgeon pies. Sturgeon with cherries and dates. Caviar. Sturgeon pasta fried with oranges. Sturgeon tripe on bread, and so forth. The author of this meal, a chef named Giovanni Battista Rossetti, was greatly admired in his time.

Perhaps the most significant divide in the history of chefs and their fame is before and after the invention of the restaurant. Until the late 18th century, when restaurants were first established in Paris, great chefs cooked for ecclesiastical, aristocratic, or princely employers. The leading chef of the 19th century here, Marie Antonin Carême, followed this older career mode. He ran the kitchens of the Prince Talleyrand, the Prince Regent of England, the Baron de Rothschild, and was offered a job by the Russians czar, which he refused. Carême was certainly a celebrity chef. But he was also the last to spend his entire career in the employ of private individuals. He was famous because of his definitive published recipes, but few people had an opportunity to sample his cooking.

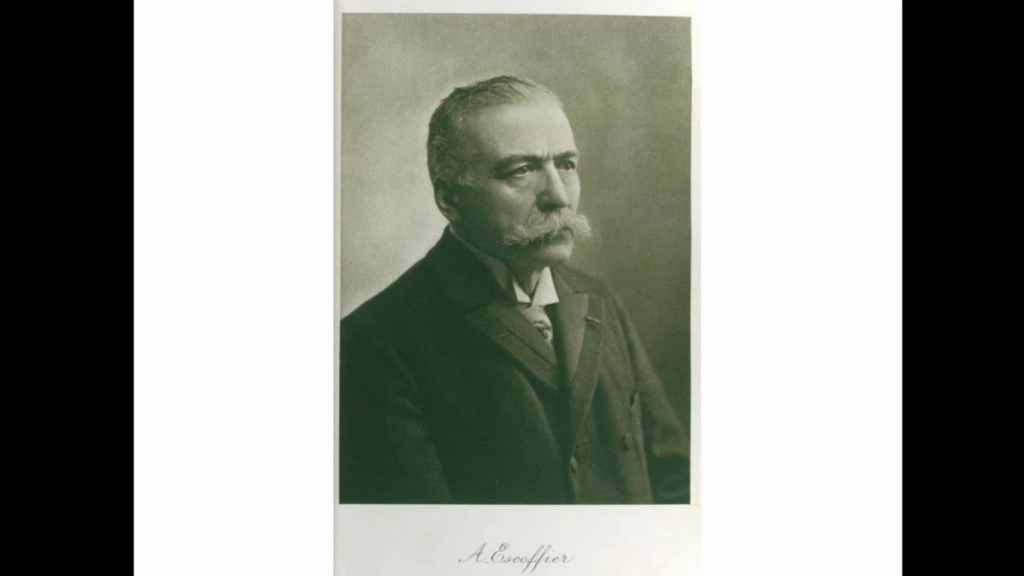

Contrast with the experiences of another authoritative French chef, Auguste Escoffier, whose career closes the 19th, and opens the 20th century. Escoffier collaborated with César Ritz, manager of the Savoy in London and the Ritz Hotel in Paris. And then after Ritz had a nervous crisis, Escoffier returned to London as the chef at the Carlton Hotel.

On one occasion, Escoffier prepared a dinner for Kaiser Wilhelm II featuring his creation, veal Orloff. The German ruler told the chef that while he, Wilhelm II, was emperor of Germany, Escoffier was “the emperor of chefs.” Escoffier cooked a magnificent one-off meal for the Kaiser, but his regular job was for an immense affluent public. Restaurants have allowed chefs to have a large audience.

An invention of the 18th century, the restaurant was distinct from a tavern, chop house, inn, or take-out establishment. All of these have always existed. The restaurant was new because it was a destination, not a convenience. Rather than eating at a crowded board, whatever the landlord set out, you could arrive at a range of possible times, sit at a separate table with your friends, and order from an extensive selection of dishes. Restaurant chefs were no longer dependent on the whims of wealthy patrons.

This does not mean, however, that grand cuisine as a spectacle was over. Nineteenth century restaurants offer dishes as splendid as those of the Middle Ages, requiring days to prepare, immense cooking skill and decorative ability, such as this game purée on the top and the partridge chartreuse on the bottom.

The nature of the meal service and the look of the table setting changed dramatically in the 19th century. The old, so-called French, form of service placed the entire first course on the table before the guests entered the dining room. This provided a dazzling spectacle of food on magnificent serving dishes, arranged in colorful patterns and shapes. There were only two or three courses for French service, but each one might consist of dozens of dishes. No single diner could try everything, but the meal was convivial in the sense that you depended on neighbors to pass things to you, or on footmen standing behind you.

In 1805, the first celebrity restaurant critic, Grimod de La Reynière, ridiculed as excessive the dinners typical of the era before the French Revolution, where sixty guests might be served over 120 dishes just for the first course. And for sixty diners he advocated a frugal thirty-five dishes merely, for each of three courses. A modest 115 in total. Who were these people? How could they dine like this? I don’t have a good answer for this.

The French service was perfected in the setting of a palace, while the Russian service came into favor with the advent of the restaurant. Russian service gradually took over between 1830 and 1880. And here there were fewer dishes per course, but many courses. This is what we are familiar with. It meant the table was more decorated because the profusion of food did not itself provide the required grand effect. Flowers, epergnes, wine glasses, chargers, plates, fish forks. The weighty look of the Victorian era replaced the small plates and minimal table décor of the French service, where the food itself provided the beauty. Modernist restaurants have tended to dispense with the starched tablecloths and multiple wine glasses look. But now the presentation of the food has become once more highly stylized.

From the point of view of the chef, both systems had advantages and disadvantages. The French service meant there was no way for the food to be piping hot, obviating that problem. A huge number of dishes were prepared, but there were only a few courses. In the kitchen, the Russian service meant a constant stream of orders, bringing dishes back and forth, and it required lots of waiters and precision timing.

The Russian meal service is also either long or rushed. Charles Ranhofer, chef at Delmonico’s in New York from 1862 until 1892, said he expected a fourteen-course dinner to take two hours and twenty minutes. Ten minutes per course. But he was quite happy upon request to accelerate the speed to about eight minutes per course so the repast might conclude in under two hours. And my original intention was that this would evoke gasps of astonishment, but since Noma is able to do this, maybe not.

Now, historically most restaurant chefs were men, while the overwhelming majority of domestic cooking was performed by women. This is a unique profile in which professional and home practitioners have been divided by sex. Some exceptional women did manage to become renowned chefs. The so-called Mère Lyonnaise made the food Lyon famous and created a self-perpetuating gastronomic culture.

In New Orleans, Madame Elizabeth Kettering Begue was the most celebrated chef at the beginning of the 20th century. Of German origin, she mastered the Creole cooking of New Orleans. Her restaurant’s main meal service was at eleven o’clock, a version of the German institution known as the second breakfast, here intended for the convenience of butchers when they finished their business in the neighboring meat market. Discovered by tourists around 1890, these bohemian breakfasts, as they were called, became wildly popular and constitute probably the first form of brunch, a particular American passion. Liver with bacon and onions was Madame Begue’s most famous dish. Again, maybe a little disappointing.

Restaurants have allowed chefs to be creative and to become celebrated, not just for mastery of classic dishes such as chartreuse of partridge, but as inventors of new things. So, Ranhofer’s lobster à la Newberg at Delmonico’s; Escoffier’s pêche Melba, named after the great opera singer; or Jules Alciatore’s oysters Rockefeller at Antoine’s in New Orleans.

Of course there are disadvantages to restaurants. The public is inclined to be unpredictable, fickle, easily bored, herd-like, and not always appreciative of quality. And I say this of course as a non-chef and member of that public.

Restaurants in the 19th and 20th centuries renowned for their food have not always had famous chefs. Our colleague Alain Senderens is an exception, but most great Parisian restaurants such as Taillevent or the Tour d’Argent were known for their proprietors and front of the house managers. Restaurants in the French provinces were more likely to be run by chef owners such as Fernand Point of the legendary La Pyramide in Vienne, or François Bies of the Auberge du Père Bise at Talloires.

The rise of modern celebrity chefs means a change in the balance between the restaurant as a stage set by its managers, where the chef is literally in the background, and the chef-driven restaurants. The waning of France’s traditional dominance over what is defined as grande cuisine is a key factor in building a new kind of fame. As long as French cuisine was the international standard, the best chefs were considered master craftsman practicing a received skill, a body of knowledge that could be traced back to what Taillevent or the chefs at Versailles learned and later taught. The end of unquestioned French power to define gastronomy for the entire world is perhaps the most significant event in the modern history of restaurants and cuisine. And I say this not as something that I think is a great idea but just as something that has happened.

In 1969, the restaurant guide authors Henri Gault and Christian Millau were asked by the American magazine Holiday what is the greatest restaurant in the world. And they contemptuously dismissed most of the globe, including Italy. Gault said of Italy, “I don’t have a single exciting memory except for the scampi at Harry’s Bar in Venice.” For Spain, “ordinary and heavy food.” For Denmark, they agreed that little children like Danish food a lot. As for the United States, the best restaurants there were French anyway, so why bother? Mulling over about twenty eligible restaurants in France Gault and Millau came up with a tie for first place between the restaurant of Paul Bocuse and that of Jean and Pierre Troisgros. This Holiday interview was a last manifestation of the serene assumption of the superiority of French gastronomy before la nouvelle cuisine of the 1970s started breaking it apart. As it happens, Gault and Millau both named and championed nouvelle cuisine.

Gault and Millau were prescient in this article in one observation particularly, it seems to me. The difference between the Troisgros brothers who in 1969 they said were working for the sake of art within an established tradition, and Bocuse who they said was working for glory. And his food was lighter, more playful and creative. Partridge chartreuse, to be sure, but Bocuse used juice from the pressed partridges rather than the meat of the bird.

Restaurant cuisine and the outlook of chefs would tend to follow the Bocuse example in the next decades, and in fact the Troisgros themselves took this path as well rather than serving as custodians of an unchanging heritage. This is not to say that chefs suddenly discovered innovation whereas before they had merely followed precedent. Grand masters of the past like Scappi, La Varenne, Carême, and Escoffier, made earthshaking changes in cuisine. But they replaced one authoritative system with another. What has happened since the 1970s, accelerating since the 1990s, I would say, is the fragmentation of authority. The absence of any agreed-upon code, whether an old one or a new one.

Chefs still influence each other, of course. Especially with regard to technique. But less in the creation and definition of canonical dishes. What we are seeing in the 21st century is fidelity not to tradition but to ingredients. This is appropriate to a food world undermined by industrial processing, agricultural unsustainability, mass market food, and ecological damage.

So Alice Waters, just as an example. Leading chefs in recent years have tended to see themselves as advocates for a terroir, but they have expanded the definition of basic ingredients found in that locality to include wild plants or previously-ignored varieties— I can’t remember how many kinds of horseradish René says grow in Denmark, but it’s over a hundred.

Chefs have encouraged the restoration of forgotten breeds, of agricultural products and livestock. A chef is not a contemporary artist, exactly, who can simply do away with traditional techniques and training. But the way is open, it seems to me as an outside observer, for more creativity than in the past, and that gives chefs more opportunities to achieve artistic and creative status. Yet as Alex Atala has said, creativity isn’t doing something that nobody has ever done before. It’s doing the same thing that everybody does, but doing it better. And ideally there should be a harmony between history and innovation.

I hope it’s not just banal to conclude my time with you by saying that achieving a creative vision as a chef comes from actual cooking, and only secondarily from shaping a personality or taking positions on politics and sustainability. Our theme, “What is Cooking?” represents more than a call to return to the stove, but I think a rejuvenated sense of our surroundings and our history. Thanks so much.

Further Reference

Overview page for the MAD 4 / What is Cooking? event.