Tracy Fullerton: I want to talk about the fact that our lives today are lived at an unsustainable pace of activity. They’re driven by the quickening effects of digital technologies on all aspects of the human experience, from personal communication to business exchange, from education to politics, from pop culture to fine arts. We have accepted a rapid cycling up of the interchanges in each of our days, and really our hours and even each of our minutes.

This unrelenting pace of technologies is deeply ironic, given the original intent of them to make our lives more efficient and give us more time. But we can all attest that the actual effect of this escalation of efficiency has been to increase the pace of work and play in our worlds. To pack our experience of life more densely and to devalue things like idleness and reflection and slowness as an aesthetic in our lives, even in pursuits like games that were once thought to be leisurely.

Now, I am a video game designer and you may be thinking, “But games are one of the major culprits in this escalation of time-sucking technologies.” And that is true. Today’s digital games invite us to play at a pace that goes beyond that which we have ever experienced. So not only do we play games with fast-paced core mechanics or in quick, stolen moments of shorter and shorter gameplay throughout the day, but we value swiftness in play literally. We monetize our desire to play more quickly by charging players to move the game forward—microtransactions, really, for milliseconds of gameplay. And players speak of lag time when judging whether the conditions of play are right or not. And now microseconds decide our twitch-based online games.

The games that we play, the games that we are attracted to as individuals, as a society, say a lot about the issues that we’re grappling with in our world. So, ancient cultures invented games about predators and prey, as well as games of chance and fate, trying to divine our futures in the face of uncertainty. In the Middle Ages we invented games of territory and conquest between great nation-states. And still later we invented industrial games of economic power and materialism.

In each of these trends, society engaged in playful simulations around some of the deepest issues of the times. And we still play many of these games today. In fact we play them so much that we have concerns about becoming addicted to our play.

Our most popular games still revolve around predators and prey, war and money, but they do so on a global scale in a way that consumes players like rats in the proverbial Skinner’s box, pushing at levers until they get the win, the reward, the prize, or the pellet. These games offer play to us that moves so quickly and builds on such basic instincts that players have no time or context for reflecting on what they are playing about, what issues they are grappling with, grinding away at virtual lives in virtual worlds that are as fast-paced and pressure-filled as our real world.

Now, as a player and as a designer of games, I wanted more. More precisely, I wanted less, but I wanted more out of that less. And as such for the past fifteen years I’ve been researching the sort of blue sky of reflective play, or what we might call “slow play.”

For me, the impulse to create games that offered an antidote to the modern pace of life began in 2002 when I took a long drive across the United States. I had recently closed my multiplayer gameplay company, a technology that connected millions of players simultaneously in games that synced to their television broadcasts. After several very stressful years of development and entrepreneurship, I took a postmortem trip around the country, hiking, and camping, and reading, and thinking about what was missing in our world of play.

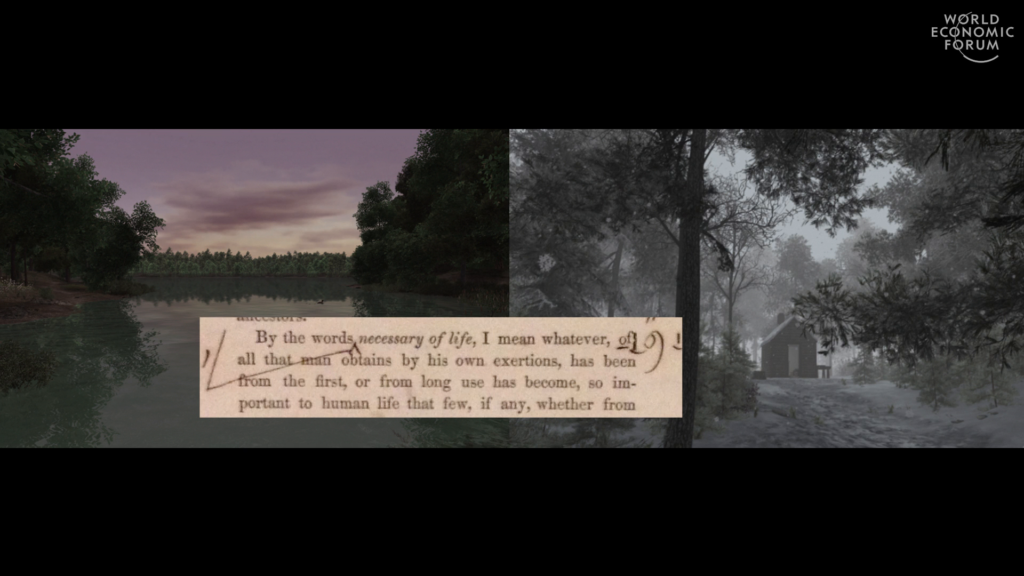

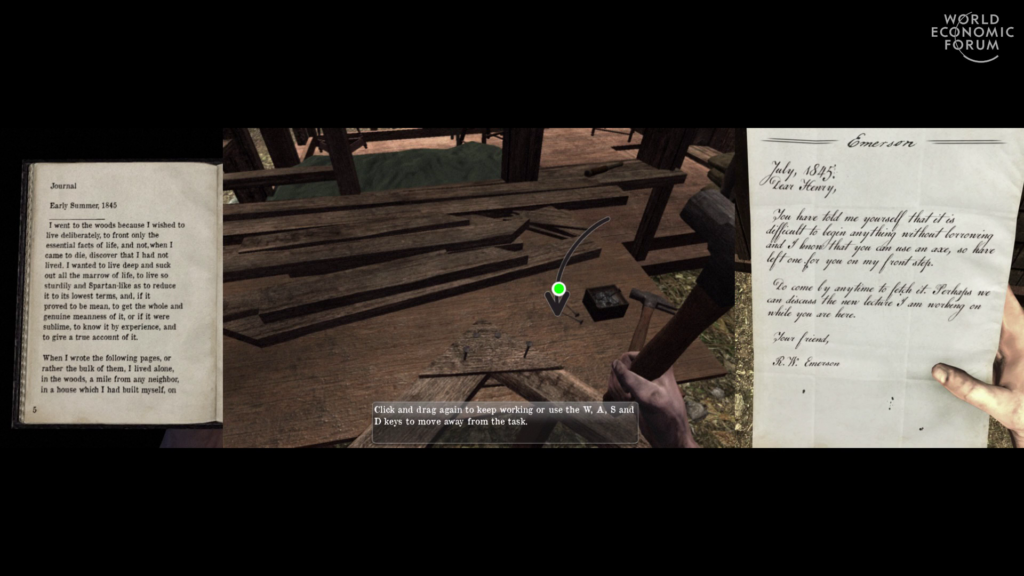

And on this trip I visited Walden Pond. And I sat on the shore to reread parts of Henry David Thoreau’s book about his experiment in living a simple life there at the pond. It was a quiet day when I was there, and I had the pond to myself. And as I read I began to feel a sense of time and how long it had been since I had a slow day. And this moment in the book, like so many others, stood out to me.

Sometimes, in a summer morning, having taken my accustomed bath, I sat in my sunny doorway from sunrise till noon, rapt in a revery, amidst the pines and hickories and sumacs, in undisturbed solitude and stillness, while the birds sang around or flitted noiseless through the house, until by the sun falling in at my west window, or the noise of some traveler’s wagon on the distant highway, I was reminded of the lapse of time.

Henry David Thoreau, Walden

And you may be thinking, “So what?” What does this pastoral thinker, this naturalist and philosopher born 200 years ago this coming July have to do with the rapid-paced world of video games and technology that we live in?

I think that Thoreau and the experiment that he set for himself in living has quite a bit to do with the dilemmas that we face every day when we confront the technologies we’ve developed to make our lives “easier,” “more efficient,” and perhaps by accident, faster and less sustainable.

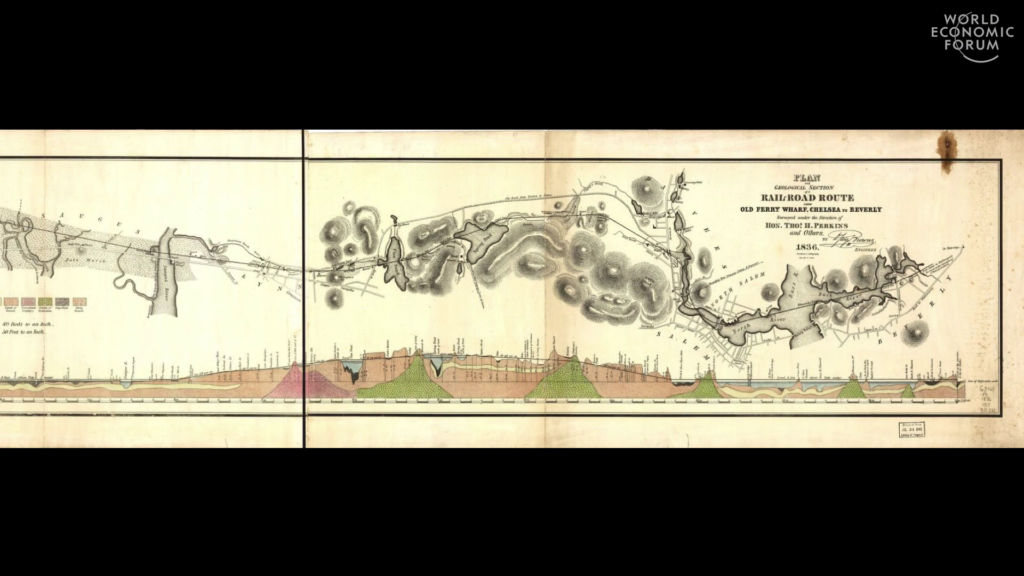

In 1845 when Thoreau went down to the woods to conduct his now-famous experiment in living simply in nature, he was sitting on the narrow edge of a particular moment of time, and he knew it. The railroad and the telegraph were just coming into general use and he could already see the pace of life around him in the small village of Concord where he lived accelerating, quickening with the advent of these technologies. Suddenly, people were living on railroad time, rushing up and down to Boston and living their lives by the punctual comings and goings of the trained in a way that changed the traditional pace of life in that village forever.

Thoreau’s experiment in stripping his life to its simplest elements can be seen as an early counterargument against this quickening that we are still grappling with, perhaps a harbinger of today’s slow living movement and its charge to reclaim a more humane pace of life for existence. We may call our pace of life Internet time rather than railroad time, but it is only a relative difference. The concept is the same. And perhaps the antidote is similar as well.

When Thoreau set out to reexamine life, to strip it to its essence, he didn’t go far—only a few miles away from the quickening pace of life in his hometown. But he went far enough to get a sense of perspective on the changes he saw in society. And he didn’t go into the wilderness, just far enough into nature to forefront it in his view. To play with the idea of nature in contrast to society.

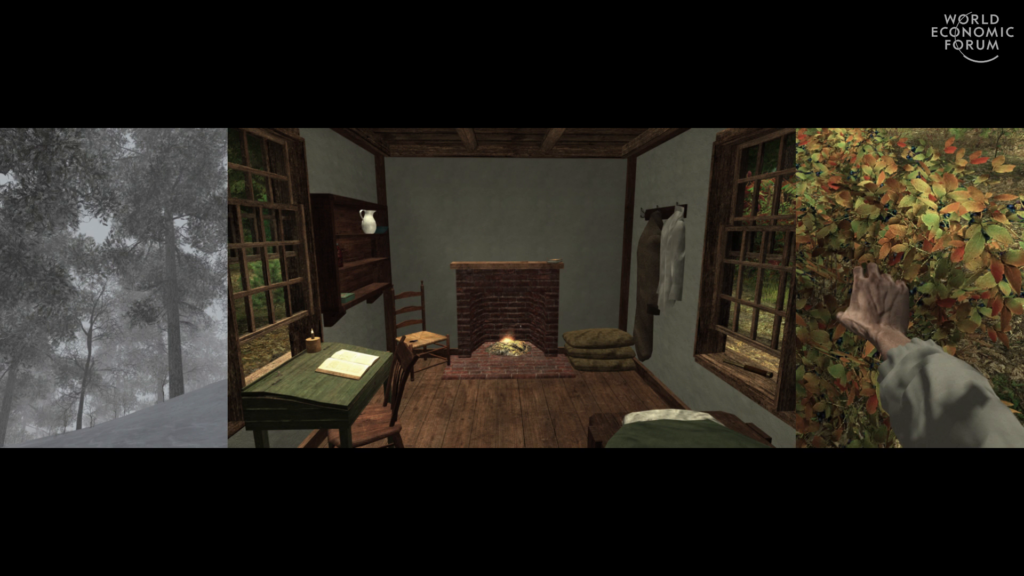

In some ways we might say that his experiment in living simply was a kind of game that he was playing with himself, setting up the rules of his experiment and seeing what he might find out about life by playing those rules. And as a game designer that idea intrigued me. And as I sat on the shores of Walden and considered the pace of life that I had been living, that we have all been living, it seemed to me that like Thoreau I needed a game that would allow me to play slowly, deeply, and reflectively rather than yet another game that kept my heart charging, my fight-or-flight reflex honed. I needed to play Thoreau’s experiment, but I wanted to play it using modern technologies to bring it to life wherever I was.

So while it might seem ironic to some, to me it seemed a perfect fit to create a virtual nature for modern readers to experience Thoreau’s words and ideas. Thoreau himself actually was an intuitive engineer, adept at understanding systems. He invented a better graphite mix for pencils, which was his family business. And of course it was also the technology of choice for his own creative writing process. And he made sure that his books were bound using the most modern technologies.

So to me, creating an immersive translation of his experiment was in the same spirit as creating a modern illustrated edition of the work. If you think about it, every year thousands of schoolchildren in America read Thoreau account of living slowly and simply. But they do so while sitting in crowded urban classrooms, without any connection to the natural world he was immersing himself in. What if I could give players like these the chance to live deliberately in nature wherever they were? Whatever their current pace of life. We don’t all have the opportunity to take two years out of life to ask the kind of questions that Thoreau did. But we still need to ask ourselves these vital questions, perhaps now more than ever. And play is the perfect vehicle for such questions.

In play, we can challenge ourself to live lives we never thought were possible. We can take chances, we can make different choices, and we can discover outcomes that may lead us to ideas that we can bring back with us to our real lives. Play is practice.

So what if we practice playing deliberately, rather than instinctively? What if we played a game slowly, and simply, and reflected on the choices we were making within it? What if we played a game about living in nature and watching it change over time, and learning its secrets, and loving its beauties? How would that kind of slow play enhance who we are as people, as citizens of the world, a world that’s in crisis?

And so I invite you to play a game of Walden; or, life in the Woods. To play deliberately; to reclaim these technologies that’ve quickened our lives, for a slow game about living in nature and questioning the inevitableness of our lives. A quiet game as an antidote to turbulent times.