danah boyd: The energy here is absolutely spectacular. It is a total delight to be here with you today. You know, it wasn’t just that I’ve been wanting to come here for many years? We joked that they’ve been asking for five years and every time I’d be like, “I’m pregnant,” or, “I’m having a baby.” And it was a really awkward thing, so I promised that as soon as I stopped having babies I would come and join you. So there’s been three babies, but now I’m here, and I’m really delighted to be here.

So, the talk that I’ve prepared for you today is sort of a strange collage of issues all meant to come and challenge this question of algorithms. But it’s done in these different pieces, so work with me and tell me how this works.

By 2008, paranoia about online sexual predators had reached an all-time high. It was this constant refrain where people were saying that the Internet was dangerous for kids. You heard it in the US, you heard it in Europe. And it was the concern about originally MySpace and then Facebook; this was a site of serious danger. The US Congress had started putting together laws like the Stopping Online Predators Act, had put together a task force about Internet safety.

And as a researcher it was a really frustrating moment. Because I actually knew all of the data about risks to young people. I could tell you in gory detail what was actually going on, what was actually making young people unsafe. But that didn’t matter. Because it wasn’t about facts or evidence. That should sound familiar, right? It was about whether or not people could get upset about the Internet over something, and at that moment it was sexual crimes on the Internet that was the issue.

And so it was an interesting moment to me when I was asked to put together a collection of all of the data on online sexual predation for the regulators in America. And one of the leading regulators came to me and said, “Go find different data. I don’t like what you found.”

Okay. Teenagers on the other hand were split on the topic. Some were absolutely concerned that the Internet was unsafe. They had heard the rumors. They had seen the TV show. They’d seen To Catch a Predator, and they were convinced somewhere there were kids being abducted, so they needed to be safe online.

Of course, most young people sort of looked at this and went, “Yet another way in which adults want to ruin all the fun,” right. And so they sat there and said, “Okay. Whatever. We’re going to ignore the parents and try very hard not to be seen using the Internet, when in fact that’s actually what we’re doing the whole time.”

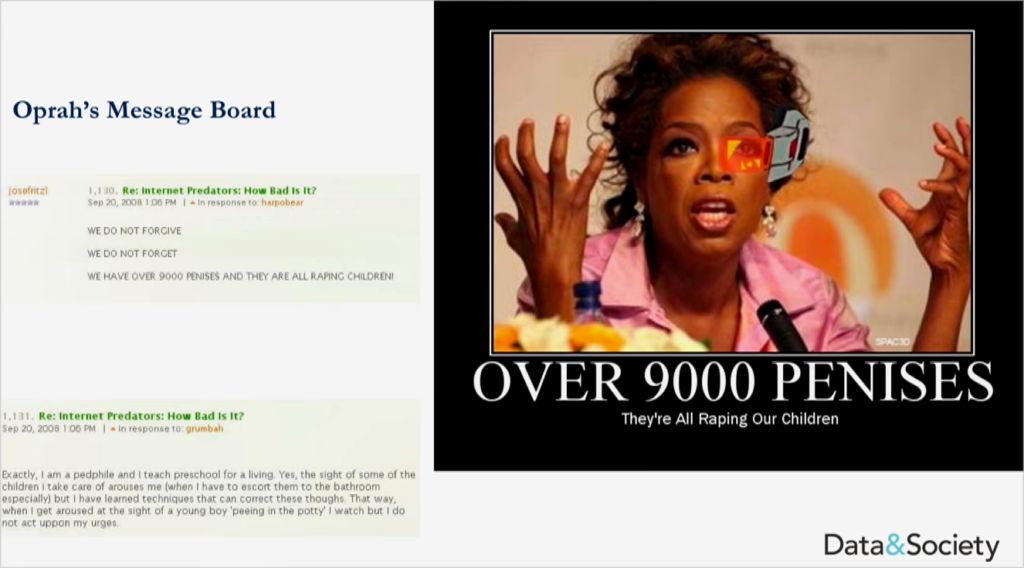

But at the same time, there was a beautiful site called 4chan. If you don’t know what 4chan is, I recommend the Wikipedia entry only. At the time it was seen as the underbelly of the Internet. Since then we’ve produce more and more underbellies, so we can sort of think about those layers. But at the time it was a site that was primarily about anime, pornography, the two major interests of 15-year-old boys. And they were having fun producing memes. So, they saw this conversation around online sexual predation and decided it was time to have a little bit of fun.

Along comes Oprah Winfrey. She decides to talk about how the Internet was a really dangerous, dangerous place. But she pulls a lot of her stories from online fora. And indeed, some of her producers were looking at this, and some of the 4chan folks were having fun. So what happened is that they managed to get Oprah to say live on national TV, a wonderful statement:

Let me read something which was posted on our message boards from someone who claims to be a member of a known pedophile network. It said this. He doesn’t forgive. He doesn’t forget. His group has over 9,000 penises, and they’re raping children. So I want you to know they’re organized, and they have a systematic way of hurting children. And they use the Internet to do it.

Now, if you know anything about 4chan, this is hysterical, right. It’s not only are you making beautiful references to all sorts of memes (“over 9,000,” the references to Anonymous, etc.), you managed to get Oprah Winfrey to say something ridiculous on live national television. And this of course is the ability to hack the attention economy.

So. What happens as we think about trolling? Let’s shift focus for a second, because we’re going to go back and forth. A decade later, most of the systems that we’re talking about are shaped by algorithms. Search engines sift through content in order to basically use machine learning to determine what might be most relevant to any given query. Recommendation systems, ranking algorithms, they underpin huge chunks of our online experience.

But meanwhile, outside of the core Internet practices, we see the use of data-driven technologies affecting criminal justice, affecting credit scoring, affecting housing, the ability to get employment. And we’re starting to see startup after startup think algorithms are the solution to everything. AI has become hot. Every company out there is positioning itself as the AI solution to…something. No one can quite tell what they’re actually arguing but something will be solved through AI.

Now, one of the things I was fascinated by is what do we even mean by AI in that conversation? And lots of people have different theories, but what I realized quickly is that AI had just become the new “big data.” It was the mythology that if we just do something more with data we can solve all of these otherwise intractable problems.

But a senior executive at a tech industry company actually explained it to me even more precisely. He was like, “Of course all of these technology companies are investing in AI. Because what’s the alternative? Natural stupidity? We don’t want to invest in natural stupidity. Artificial intelligence sounds great.”

Well if that’s what we’re using as our basis we’ve got a problem, because then we have this question about what does accountability look like? How do we think about challenging these systems? You know, of course here in Germany you are at the forefront of trying to challenge these systems, questioning how these technologies can be used, building up different forms of resistance. Really asking hard and important questions about where this is all going. And I love artists and journalists, critics and scholars who pushed at edges, and so thank you for all of you doing that hard work. Because that’s really important.

But alongside what you’re doing there are also people with darker agendas, who are finding other ways of making these systems accountable. They’re looking at ways of manipulating these systems at scale. It’s not just about manipulating Oprah to say things on national TV, it’s about the use of dirty political campaigns, the idea of black ops advertising, the ability to use any tool available to you to manipulate for a particular agenda regardless of the social costs. And this is where we’re starting to see a whole new ecosystem unfold that has become more and more sophisticated over the last decade.

And it raises huge questions about what does it mean to hold accountable not just nation-states or corporations, but large networks of people who are actually working across different technologies. And so a lot of what I’m going to do today is try to unpack that and build that through.

But let’s start with some examples. In 2009 there was a pastor in Florida in the United States. He wanted to spread the message that Islam is of the devil. And so, as a pastor of a small church—around fifty people—he put up this sign in front of his church in order to invite people to share his views.

Now, generally speaking not that many people right around Gainesville, Florida, in the scheme of things. And so it reached different folks who grumbled. But then he got a little smarter. He said “I can actually spread this message louder through media.” And so he threatens to burn the Koran. And in threatening to burn the Koran, all sorts of anti-prejudicial organizations sort of stepped up and they release press releases telling him not to burn the Koran.

So the news media starts covering the press releases, originally in Florida but it starts to scale and scale. Once it hits Yahoo! News, once it hits Google, it becomes something that people want to talk about. And so he ends up on CNN talking about all of this, people putting pressure on him to not do this.

And so he backs down because he’s gotten a lot of attention, and this is really fundamentally what he wanted. But then the attention went away. People stopped paying attention to the issue. And so he revised it. And in 2011 he was part of a group of people who burned the Koran.

So what happened was that the news media said “No. We will not cover this, because covering this is amplifying a message that’s not important. We will not go and witness this act.”

But, a little-known blogger decided that they wanted to witness this act and write about it. And once that blogger wrote about it, it rippled its way up the chain. Back to CNN he went. It ends up on the front page of The New York Times. The New York Times of course is translated into many different languages around the world. And so what happens is that riots start breaking out in different parts of the world. And notably one of those riots in Afghanistan results at least twelve people dead, including seven United Nations workers.

Now why is this important? Journalists like to imagine that they are the neutral reporters of incidents. They have a moral responsibility to report on anything that is newsworthy. But I would argue that failing to recognize that when they do they can create harm is where we see the irresponsibility of this dynamic. Where journalism has paired and become part of the broader information and media landscape. Where we need to think about the moral responsibility of being a voice, of being an amplifier.

My colleague Joan Donovan and I have been putting a lot of time thinking about what strategic silence looks like. And most of the time when we say that, people are like, “You don’t want journalists to be silent, do you?” The head of The New York Times actually said to me that this is a terrible idea. “The US government asks us to be silent all the time and we choose that we need to report.”

And I said, “You’re emphasizing the wrong word there.” The phrase is “strategic silence.” The idea is to be strategic. And if you can’t be strategic, be silent. You need to be strategic not just about what it means to speak, but how the processes of amplification can ripple and cause harm.

Now, this isn’t something that’s just new. In fact, one of the reasons why Joan and I have been collaborating on this is that she has gone back through the history of strategic silence with regard to the Ku Klux Klan in the United States. I have looked back into the history of suicide. We know that when we report on suicide-related issues we amplify the costs and consequences. Actually, journalists as a community decided to be strategically silent. The World Health Organization put out a report encouraging them to do so.

That has all become undone because of the Internet. To give you a sense of the amplitude of harm, when Robin Williams died by suicide we saw a 10% increase in suicide over the next two months, with a 32% replication of his mechanism of suicide. These are people’s lives that are at stake.

The chain of information flow is part of what gets exploited. It’s not no longer just about going to the gatekeepers as a journalist. It’s about finding ways of moving things across the Internet, in through journalists and back around, that becomes part of the gift. And I think back to the work of Ryan Holiday, who was a…basically a person who had manipulated these systems for his advertising purposes. He figured out that the key to getting large amounts of attention was not to purchase advertisements. And that wasn’t possible if you were little-known and not recognized. It was to create spectacle that little-known bloggers would feel the need to cover because they’re paid based on the number of articles they can write. And then to move up the chain. To get the bloggers to be amplified back into Twitter, back into Google News, up into mainstream journalism. If you can create spectacle and move it across the chain, you can control the information infrastructure.

And that of course is where the trolls come in. Trolls have figured out exactly these strategies. They’ve figured out how to get messages to move systematically across it, whether they are paid at large scales by foreign states, or whether they’re a group of white nationalist looking to move a particular ideology.

And in moving across it, what they do is pretty systematic. They actually create all sorts of sockpuppet accounts on Twitter—fake accounts. And all they have to do is write to journalists and ask questions. And what they do is they ask a journalist a question and be like, “What’s going on with this thing?” And journalists, under pressure to find stories to report, go looking around. They immediately search something in Google. And that becomes the tool of exploitation. Because they come across a Wikipedia entry that has been conveniently modified to have phrases that might be of interest to them. They end up getting to web sites or blogs that have been set up for them, and that’s how narratives are moved. They’re moved by mainstream media, because they’re a tool of a variety of trolls.

And that’s why we have to ask questions about accountability. Who is now to blame here? Is it Twitter, for letting you create pseudonymous accounts? Is it the journalist who’s looking for a scoop under pressure? What about the news organization whose standards have declined because they’re trying to appease their private equity masters? Should we blame the Internet for making it so easy to upload videos, edit Wikipedia, or create your own web site? What about the reporters who feel as though they have to cover something because it’s being covered by somebody else? What you see is an accountability ecosystem, not one actor being in place.

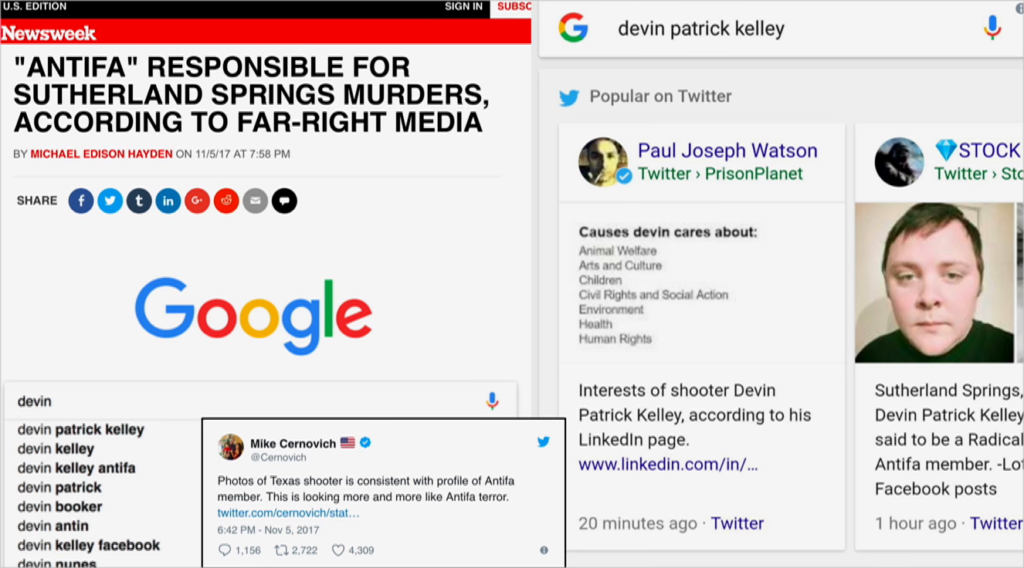

Now, let’s look at what that trolling environment looks like, and think through the responsibility of it. On November 5th, 2017 a 26-year-old walked into a church in Sutherland Springs, Texas and began shooting. Most people had never heard of the town; it’s a very small town. And now all of a sudden they got all sorts of news alerts, as we get the United States, and as many of you get overseas where you’re looking at our country going, “What are you doing?” But we get these news basically saying, “Alert: there’s an active shooting somewhere.” And every major news outlet basically alerts us. You get this stream on your phone: active shooting; multiple dead; Sutherland Springs, Texas.

So I looked at this and was like oh, I know what’s about to happen. And I jumped online to watch it unfold. And it was a beautiful moment of explaining exactly what I expected. These were far right groups who had coordinated online—they love live shootings in the United States because they like to associate the shooter with some particular agenda. And at the time the goal was to associate live shooters with antifa—particularly white shooters.

Antifa is referred to as anti-fascism, and there are people who are a part of this network but it is actually not that large. Far right communities have spent a lot of time propping antifa up to look bigger than it actually is, and to look more violent than it actually is, with the idea that if they can create it as a false equivalency the news media will feel the need to report on them simultaneously. So, far right communities produce hundreds antifa accounts on Twitter, where they responsibility for different actions. They look to be real. News organizations constantly cite fake antifa accounts in doing so.

But it’s not just about that, because what they really wanted to own was Google search. The ability to own Google search during a live shooting is extremely important, because most people who are trying to figure out what’s going on will go and search something related to the incident into a search bar.

Now, the key with understanding Google is that Google doesn’t know how to respond to basically a breaking news story. Prior to this moment if you had looked up Sutherland Springs, you would see detailed demographic histories of the city, Zillow pages that told you about properties; there was nothing of substance about Sutherland Springs.

But, what they did is they first target Twitter and Reddit. Why? Because Google pulls in Twitter and Reddit during breaking news events to try to understand and contextualize as fast as possible. So by targeting Twitter and Reddit they can actually get things going. They move across a ton of different fake accounts. They pummel different questions. They throw at journalists, asking questions. They’re like, “What’s going on with this? This is just a story.” And they’re just generally talking about it. And they start asking questions. Is it antifa? Is it antifa? Is it antifa?

And that question’s really important because eventually people start covering it in different ways. And what was priceless is that the first news organization that they got was Newsweek. Newsweek, thinking that they were being responsible, wrote an article said, “ ‘Antifa’ Responsible for Sutherland Springs Murders, According to Far-Right Media” that detailed how this was completely inaccurate.

But the joke was on Newsweek. Because what these groups cared about was the fact that Google News is at the top of a Google search. So if there’s breaking news, getting top-tier news media coverage is important. And the thing about top-tier news coverage? is that they can’t give you the whole headline because there’s not space for it in Google. There’s only a character limit. And that character when it turns out to be the first six words of that story: Antifa Responsible for Sutherland Springs Murder.

So the result of course is that everybody is looking at that as though that is the story. We see this time and time again. We see this for example in our shootings related to Parkland; the idea of moving that this is a crisis actor through the system.

Exploiting the information ecosystem like this requires a tremendous amount of digital literacy. You need to know where the weaknesses are, and have the skills, tools, and time to experiment. So who is all invested in that? There’s a variety of people who’ve been building those skills for the better part of a decade. It’s not just researchers who are moonlighting as for-profit strategic communications companies. It’s also Western teenagers who have been curtailed by their parents and find this to be something fun regardless of the ideology. It’s frustrated twenty-somethings who’ve labeled themselves as NEETs: Not currently in Education, Employment, or Training. Or betas, part of a male community that doesn’t believe that they have the power of alpha males—you may have heard the notion of an incel recently.

It’s about finding different people who are unemployed or disenfranchised, feeling as though they can game a system just like they’ve games in video games. The idea that they can come together and be something bigger than they were. It’s the gray side of what we once called call centers, because in the Philippines and India, folks who’ve been trained on trying to address content moderation have figured out all the boundaries of the major technical systems, and as a result have found ways to make a lot more money exploiting those systems for different actors. It’s activists who’re trying to change the world, who are actually playing in that. But of course, not all of those activists are progressive.

So creating memes to hack the attention economy was really begun as a youth culture experiment. But it has become the formal basis of what we think of as disinformation today.

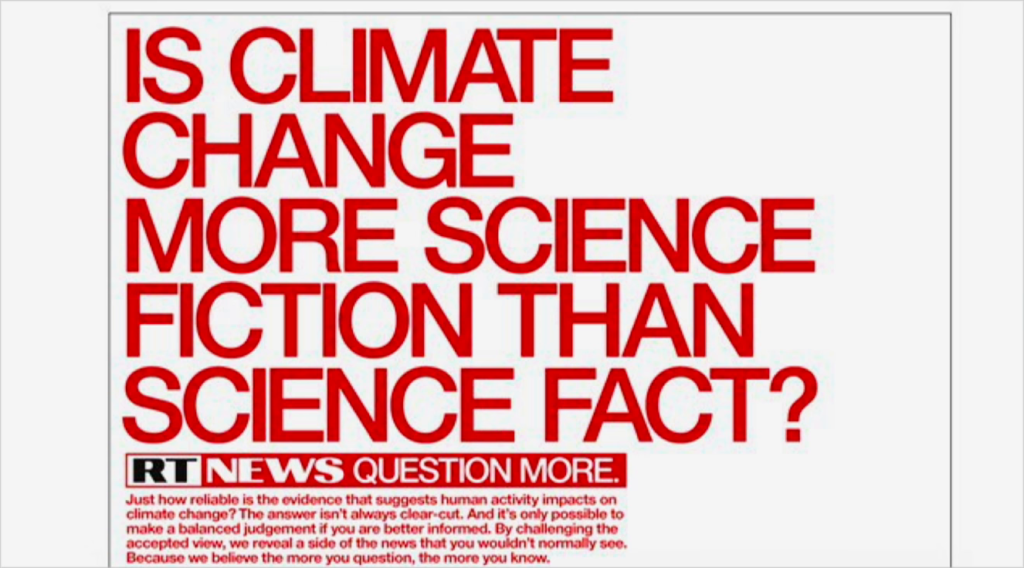

So let’s move back into the media to look at how this has begun. In 2010, Russia Today began disseminating highly controversial advertisements to ground it’s motto “Question More.” It’s a beautiful motto. It fits into every media literacy narrative we’ve ever had. And the resultant posters ended up triggering all sorts of anxiety. For example in London, posters were put up around this campaign and immediately taken down as propaganda. And then there was all sorts of coverage about whether or not they were propaganda, because they were just asking you to question things.

So let’s see what that actually looks like. “Is climate change more science fiction than science fact?” And the really small print, “Just how reliable is the evidence that suggests human activity impacts on climate change. The answer isn’t always clear-cut. And it’s only possible to make a balanced judgment if you are better informed. By challenging the accepted view, we reveal a side of the news that you wouldn’t normally see. Because we believe that the more you question, the more you know.”

Now, if you didn’t already believe in climate change, that architecture of a question would be really powerful to you. In fact, for those of you thinking within critical perspectives, just start to substitute the actual topic. Just how reliable is the evidence that suggests that there’s a correlation between exercise and weight loss? That sounds like a research agenda, right?

This is the beauty of a campaign like this. It’s seeding doubt into the very fabric of how we produce knowledge. It’s destabilizing knowledge in a systematic way. It’s by creating false equivalencies that the media will pick up on. This is a project if you’re looking to actually engage in epistemological war.

Fake news isn’t the right frame. Sure, there are financially-motivated actors producing patently inaccurate content to make a buck. But have you seen tabloid media? This is a long history of things. I mean, I love the UFO history. It’s really wonderful. But what people refer to when they talk about fake news is actually a feeling of distrust towards news creation that is produced outside of their worldview. News that’s produced by people they don’t trust. News that seems stilted from the vantage point in which they operate. And it’s why we see content that is political like RT be perceived as fake news from this context. And why a huge chunk of Americans believe that CNN and New York Times is actually fake news. Because here’s where epistomology kicks in.

Epistemology concerns how we construct knowledge people construct knowledge through different ways of making sense of the world. Some emphasize the scientific method. Others focus on experience. Still others ground what they think about through religious doctrine. And that’s all fine and well when those epistemologies align to result in the same narrative. But if you are trying to engage in a culture war? the best thing you can do is try to split those epistemologies. Try to make it seem as though they have nothing in common and they are at odds with one another. And so I love this quote by Cory Doctorow, which I’ll read in case you can’t from afar. “We’re not living through a crisis about what is true, we’re living through a crisis about how we know whether something is true.”

We’re not disagreeing about facts, we’re disagreeing about epistemology. The “establishment” version of epistemology is, “We use evidence to arrive at the truth, vetted by independent verification (but trust us when we tell you that it’s all been independently verified by people who were properly skeptical and not the bosom buddies of the people they were supposed to be fact-checking).”

The “alternative facts” epistemological method goes like this: “The ‘independent’ experts who were supposed to be verifying the ‘evidence-based’ truth were actually in bed with the people they were supposed to be fact-checking. In the end, it’s all a matter of faith, then: you either have faith that ‘their’ experts are being truthful, or you have faith that we are. Ask your gut, what version feels more truthful?”

Cory Doctorow, Three kinds of propaganda, and what to do about them, Boing Boing, 2/25/2017 [presentation slide; bolding boyd’s]

That narrative is so powerful in splitting people. And it’s so confusing to people when they don’t see a worldview outside their own, when they’re not engaging with epistemologies that are different than their own. Because what’s beautiful and troubling about this dynamic is that it’s a way of actually asking who gets to control knowledge. And it’s something that we struggle with, even those who are producing scientific evidence.

So RT’s campaign was brilliant not because it convinced people to actually change their worldview, but because it slowly introduced a wedge into a system.

Now, part of what it introduced us to is a system that has bias baked all the way through it. And here’s what we need to look at this question from another angle, which is what are the fundamental biases that underpin a huge amount of our technical systems, and how do we see that then amplified through these disinformation campaigns, and where do they come come to converge in undermining all of our data infrastructure?

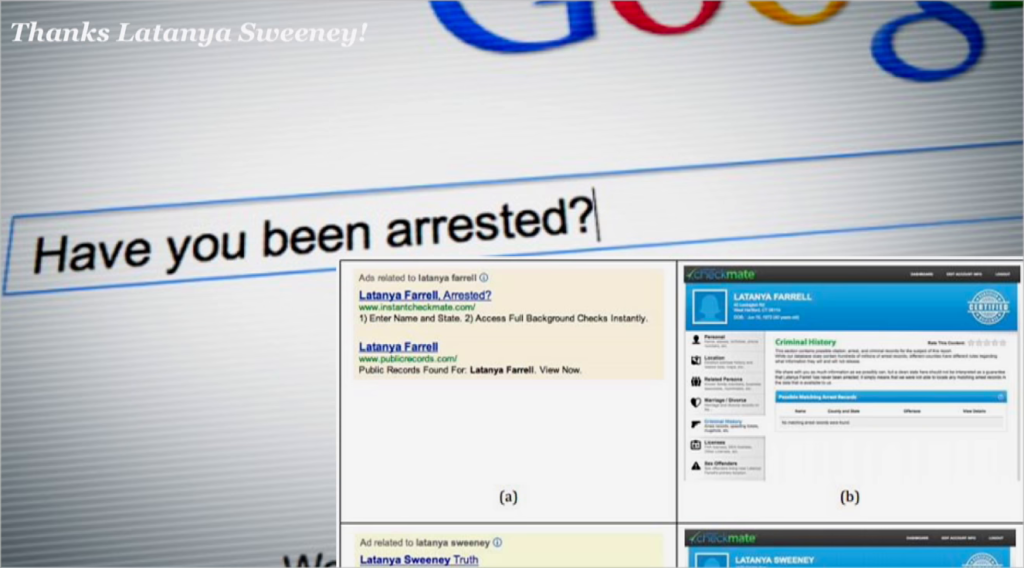

So let me start with an example. Latanya Sweeney is a Harvard professor. And she was trying to figure out where she could get a paper she had written before. And for any academic in the room, you know you’ve written a paper in a while, so you search your name and the paper in a search bar hoping you’ll find it. And that’s what she did.

But she was surprised because up came a whole set of ads. “Wanna see Latanya Sweeney’s arrest record?” And she was sitting here going, “I’ve never been arrested. What’s this about?”

And so, she was with a journalist at the time. They started asking questions trying to figure out what was going on. And Latanya had a hunch. She figured that what was going on had more to do with the fact that she was searching for a name than it had to do with her name in particular. And she guessed accurately that if she threw a variety of different names into the search engine she would get different ads from this company.

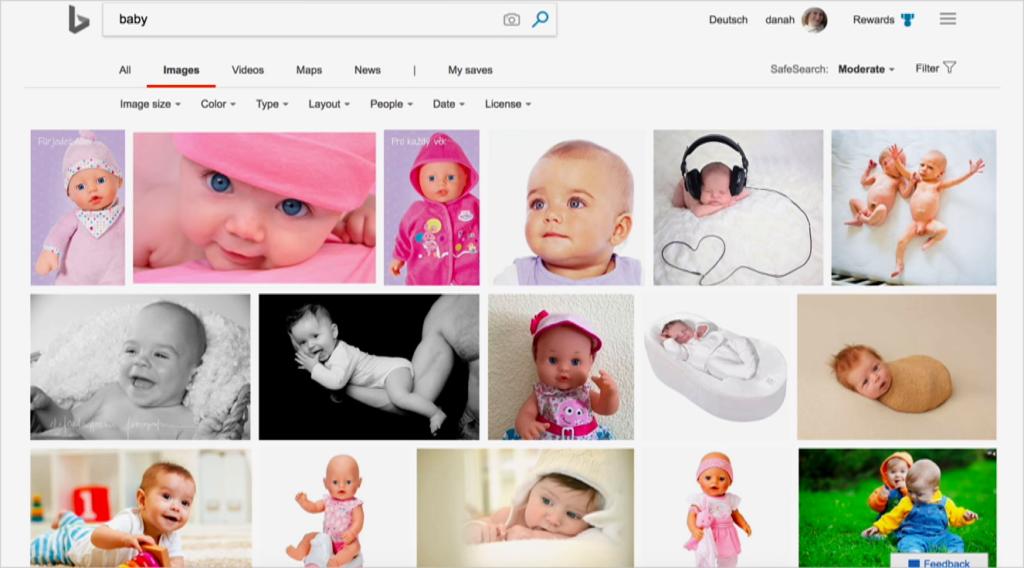

It seems as though the company had been producing six different ads with six different approaches to things. So, she took the most popular baby names in the United States that are associated with African American culture, and the most popular baby names that are very classically and traditionally associated with Caucasian culture, and she threw them at Google to see what ads would pop up.

I’m sure it doesn’t take a PhD to figure out very quickly that the names that were white baby names were not likely to get criminal justice-related products. They tended to get ads for “background checks.” But the ads that were associated with black names tended to be far more likely to be criminal justice-related products.

So what’s going on here? Google doesn’t actually let you pivot off of race, and Latanya knew that. She was the former Federal Trade Commissioner’s technology expert. So she knew something else was happening. What happened is that the way that AdWords works is that you can pivot off of something like “name” and then to figure out which names are better depends on who clicks on things.

So what happened is that people, average people, you, searching for different names were more likely to click on criminal justice-related products when searching for black names than when searching for white names, and so the result is that Google learned the racist dynamics of American society and propped it back out at every single person, right. That amplification power is taking the localized cultural bias and amplifying it towards everyone.

And this of course is the cornerstone of a huge set of problems when we look at search engines. Now, take a search like “baby” or “CEO.” I’m sure you’ve figured out by now that when you search for “baby” you get this strange collage of white babies in perfectly posed, beautiful sensibilities. “CEO” gives you a bunch of men wearing suits, usually white.

But what’s going on here? Are these search engines trying to give you these results? No. Here’s what’s going on or how this happens. Why do people use image search? They use image search to produce PowerPoint slides like this one, right. And so what happens is that they search a generic term like “baby” not because they’re looking to see what categories of babies exist, but because they want a picture of a baby for their PowerPoint deck.

And so what they’re looking for is stock photos. Stock photo companies have figured that this is a really good way of making money. Put small stock photos into the process, get people to click, they’ll buy the big high-res one for their PowerPoint. And so they’ve mastered SEO. They’ve gone and optimized by labeling pictures with search terms that are likely for PowerPoint decks, and throwing that into the search process. And as a result for a query like “baby” you don’t get natural babies. Because most people don’t label photos that they’ve taken of their own children with “baby,” right. They get it because it’s stock photos.

Now, what’s problematic here is that stock photos are extremely prejudicial in the way they’re constructed. Not only are they perfectly poised in like, weird ways that like—who puts a headphone like that on a baby, right? Like who does that? Not only are they done in this particular constructed manner, but they are highly normative towards different ideas of who is “valuable,” “attractive,” etc. within society.

And so you have a problem, because the photos coming through the stock photo companies for a term like “baby” are primarily white. And so then what happens for a search company, right? They see all of this stuff. It looks like it’s highly-ranked because the SEO has been very much manipulated in different ways. They can’t actually see race of an image like this, so they don’t know what’s going on. But all of a sudden there’s a media blowup telling them that they’ve done something bad so they start to look.

The problem is that they can’t actually see what’s going on here. And so then they rely on their users. They start trying to randomize other pictures to put up and see what what the users will click on. Well we’re back to really racist users. Because the users don’t click on pictures that are not photogenically perfect. They don’t click on pictures of more diverse babies. They click on pictures of white babies under the age of one. And so how then do you deal with a society that’s extremely prejudicial at multiple angles feeding the entire data system?

And here’s where we have a fundamental flaw of any kind of machine learning system. Machine learning systems are set up to discriminate. And I don’t mean that in the cultural sense that you’re used to. When we think of discrimination we think of the ability to assert power over someone through cultural discrimination. What these systems are set up to do is to segment data in different ways, to cluster data. That is the fundamental act of data analysis, is to create clusters. But when those clusters are laden with cultural prejudice and bias, that ends up reinforcing the discrimination that we were just discussing.

Now, grappling with cultural prejudices and biases is extremely important, but patching them isn’t as easy as one might think. Because figuring out how to deal with people who are spending tons of money and energy gaming systems, coupled with prejudicial activities of search by average people, makes it a really hot place to try to figure out what’s going on.

It’s also where things get gamed. Now let’s talk about some of the gaming problems here. In 2012 in the United States, it was really hard to avoid the names of Trayvon Martin and George Zimmerman. Zimmerman had murdered the teenaged Martin in Florida, and he had claimed self-protection under our ridiculous laws called stand-your-ground. I’m not going to defend US gun laws. I know the feelings here. The feelings are shared, but in the United States many people believe that these laws are important.

And so what happened was that there was a whole set of dynamics going on around gun laws, around brutal murders of young black men in our country. And so this hit a level of fervor in the United States. Every media outlet was covering it.

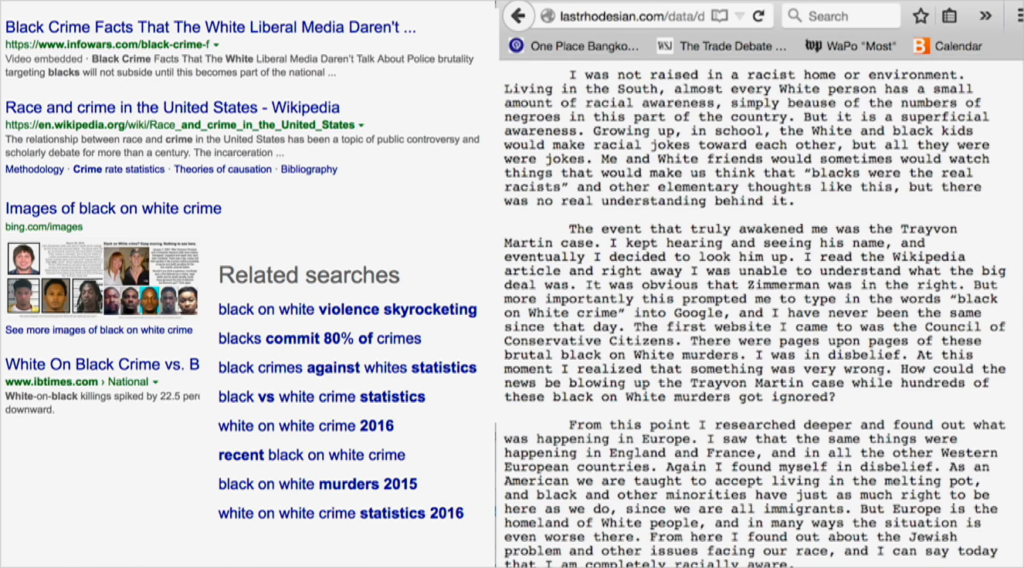

Well, not all young people pay attention the media outlets. And in South Carolina, a white teenager by the name of Dylan Roof wasn’t paying much attention to the media, but he kept hearing this in the ether somewhere. And finally he decided to search the names “Trayvon Martin” into Google to figure out what was going on. And he decided to read the Wikipedia entry. And the Wikipedia entry was written, as Wikipedia entries are, in a very neutral voice detailing the dynamics. Coming from the position he was coming from, he concluded by the end of the Wikipedia article that George Zimmerman was clearly in the right and that Trayvon Martin was at fault.

But more importantly, there was a phrase that was put inside that Wikipedia entry for him to stumble upon. That phrase was “black on white crime.” He took that phrase and he threw it into Google. We know this because he detailed in it in his manifesto. He took that phrase into Google, and by running a search on “black on white crime” he came to a site called The Council for Conservative Citizens, which is a white supremacist, white nationalist site.

Results is that he spent the next two years going into forums on white nationalism, exploring these different issues, coming to his own formative ideas of white pride in ways that are deeply disturbing and deeply, deeply racist. And on June 17th, 2015 he sat down with a group of African American churchgoers during a Bible study in South Carolina. He sat there for an hour before he opened fire on them, killing nine and injuring one. And he made it very clear both in his manifesto and his subsequent trial that he wanted to start a race war.

So what’s going on there? There are two things that you need to unpack when you understand the manipulation of these systems. The first is the notion of red pill. A red pills is a phrase like “black on white crime” that is meant to entice you into a learning more. That phrase doesn’t actually mean something until it means something, right. Which is to say that no process of Wikipedia would’ve actually excluded the term “black on white crime” from a Wikipedia entry before this case had sort of unfolded.

Now, of course the red pill comes from The Matrix, and it’s the moment where Morpheus says to Neo, “You take the blue pill, the story ends. You wake up in your bed and believe whatever you want. You take the red pill, you stay in Wonderland and I show you how deep the rabbit hole goes.” And from a white nationalist perspective, the idea is to set red pills all over the place that invite people to come and explore ideas of white nationalism. It’s a large invitation. Most people don’t trip over them. Some do, and the moment they trip over them they’ve got an invitation.

And that’s a really interesting moment for radicalizing people. Because the group is trying to stage radicalization through serendipitous encounters, right. And huge amounts of the Internet are flush with all sorts of these terms meant to invite you into these frames. It’s also true for talk radio and other environments.

And then you go back to search, right. And the problem with search is that there’s a whole set of places where search queries are crap. Michael Golebiewski likes to talk about these as data voids. Data void are the space where normal people don’t construct web sites to actually give counternarratives to white nationalist ideologies. People do not begin a search query with “Did the Holocaust happen?” They don’t create websites with “white pride” when they’re trying to push back against radicalization. Until of course this becomes visible.

Once you actually have these terms, you have an ability to roll them out and to constantly use search engine optimization to master them. And one of the problems is we don’t fill these data voids until we find out about them. And then we fill with very serious content. The Southern Poverty Law Center, factcheck.org, Snopes, all tell you that this is white supremacist, white nationalist propaganda. But the problem is that if you’re already down these paths, if you’ve already entered the funnel, you don’t care about those sites, you want to learn more. So there’s a question of how you stop those funnels in the first place.

Now, one of the things we start to see in this process of data voids is that even when something starts to get filled—so black on white crime is something that started to get filled by the Roof case and people started fleshing it out—all you see is a shift. And so white nationalist talk radio now talks about white victims of black crimes, which is a new data void out there.

Alright. We’ve gone through back into darkness, let’s come back out into trying to figure out where this fits into broader sets of context. The more power that a technical system has, the more that people are intent on abusing systems. And the way that you actually remedy this is not just by trying to patchwork across that, but it’s by trying to understand the dynamics of power and the alignments of context.

And let’s do this by moving away from the search and social media space, because it’s important to see this in other environments, and to look at how incentives stack up. So consider a main like precision medicine. My guess is that there’s no one in this room who’s like, gung ho “we should not solve cancer,” right. Generally speaking, we believe in addressing medical challenges. We may not want to pay for them, we may not want to deal with the consequences of trying to do that work, we may not want to invest in it in different ways. But we generally believe that medicine is a good thing to pursue. A scientific process that’s important. And what we then care about is how do we do it ethically. How do we do it responsibly. We look back to the history of abuses in medicine. Things like Tuskegee, or things like the Nazi experiments, and we say we’ll never do that again. But if we can bound the process of collecting and managing data in an ethical manner, we generally believe in it.

Well, where does that data come from? I argue that there’s sort of three different ways in which most of the data ends up in the system. The first is what you would think of as data by choice. Data by choice is the idea that you’ve given over that data by consenting, with full knowledge of everything that we’ll use by that data. This in many ways is what a lot of the tech industry hopes is how they collect data. It’s what a lot of scientists hope about how they collect data. And in an ideal world it’s how we would get data in the first place. The difficulty is that even those consensual moments start to get corrupted in different ways.

Now, most data is not done in terms of consensual form. Most data is not actually done in the extreme opposite. But let’s look to the extremes in order to understand this.

At the opposite end of the extreme is data by coercion. Data by coercion is best exemplified by a really morbid American policy. So in the United States, there was a ruling by the Supreme Court that said that collecting DNA at the point of arrest was equivalent to collecting a photograph or a fingerprint. Our justices clearly have not taken basic biology. And so they missed the idea that there’s maybe a lot more in DNA than a recognizable identifier.

And so the police department in Orange County in California decided to take this to a logical extreme. They created a program called “Spit and Acquit” which is, the moment in which somebody might be arrested, they asked them to provide genetic material, and if they provided genetic material they would not be arrested. They would be acquitted.

And so they built out huge databases of genetic material. And in building out those huge databases of genetic material, we have situations like what we saw last week, which actually was just a voluntary process, where it’s used then for law enforcement. Only one of the things that’s happened, for example, from the Spit and Acquit programs in Los Angeles is that law enforcement officers show up asking to meet your brother, only you didn’t know you had a brother. That’s at the coercive end, because it’s not just coercive for you, it’s coercive for your entire social network.

Now, the vast majority of data that we deal with in this ecosystem is data by circumstance. This is you posting things on Instagram because you’re hanging out with your friends and you hope everything will be okay. And the reality is that most of that mess of data is in that circumstantial environment. So when we get outside of precision medicine we don’t necessarily think about data that’s been done for consent.

Now, we look at precision medicine as an opportunity, a place where we can actually pursue things. Because generally we believe in the pursuit. There are other realms where we don’t necessarily agree on what the pursuit is. Consider the realm of policing. Not everybody has the same view on police. To give you two extreme versions on this, some people believe that policing is entirely about weeding out bad actors and punishing them. It’s a punitive model through the system. Other people believe that is about different kinds of creating community trust and support. Obviously what you want is some…where in the middle, but probably where is really complicated.

So the difficulty is that depending on what your goal is, you’ll do radically different things with a data analytics process like by predictive policing. If your goal is to arrest people, if that is your target, you will send police to a very different set of directions. You will also discourage them from spending time in the community, because that way they will be less biased. And that means that the goal of your system actually affects your data analytics process.

Now, criminal justice is a fraught area in general. And let me twist it in a slightly different way, because there’s a whole ecosystem called “risk assessment scores.” Risk assessment scores are the idea of taking information and determining whether or not somebody is a risk. The difficulty with risk assessment scores is that we end up with biased data, as were not surprised about.

But we also end up with this challenge about how people take that information to being. Judges, in theory, are supposed to receive those scores and be able to override the information, to be able to make a human judgment on top of whatever that score is. And that’s part of what gets the scoring process off the hook, right. Human judgment steps in.

But there’s something funny that happens. Judges are elected. Or they’re employed in one way or another. And as a result, what happens is that when those risk assessment scores are put into motion and judges look at them, they’re incentivized to go in alignment with them. To basically work with in whatever those scores are. Because if they override it, they could be in big political heat for it.

And that’s where humans in the loop aren’t all that we think they might be. Part of what’s fascinates me about humans in the loop is that we often use it as a solution as though human judgment is the best thing ever, and that it would actually be helpful to get humans there.

Well, my colleague Madeleine Elish went through the history of the Federal Aviation Administration in the United States. This is the administration that oversees things like autopilot. And in the 1970s there were a series of hearings about whether or not we should have autopilot in place. Autopilot was unquestionably safer for fliers.

To this day, any of you who fly on a regular basis, you’ve heard that person come on the loudspeaker telling you that they’re your pilot and they’re there to make it a safe and wonderful place. And that person most likely hasn’t flown a plane in a long time, alright. Because that person is there to babysit an algorithmic system. And they’re only responsibility is to step in when that algorithmic system fails and be able to successfully absorb all of the pain and respond fast.

Most people can’t do that. They’ve been deskilled on the job. They haven’t been flying planes, and certainly not in a high-risk situation. They don’t know why the failure occurred. And as a result, most of those planes collapse because of human error.

Now, that’s the funny thing. Because what Madeleine argues is that really, the whole point of that pilot isn’t really to help out in an emergency. It’s to be an organizational liability sponge. To absorb all the pain and responsibility for the organization. To be the one accountable for the technology, in some sense. And she describes this as a “moral crumple zone,” crumple zone being the part of the car that receives impact. And we put humans in that process.

If you want humans in the loop, a lot of it is about understanding again that moment of alignment and that moment of power. I’m on the board of a organization called Crisis Text Line, where people can write to trained counselors when they’re in the moment of crisis in order to get support. And we actually use a ton of data analytics to try to make certain that our counselors are more sophisticated in everything that we do. We try to figure out ways of training the counselors based on the things that everybody else has learned. And we can do this, first because we’re a nonprofit, second because we’re trying to actually make things better for those in crisis at any given point. And it’s better because everybody agrees on that mission. And that alignment is beautiful. It’s also very rare.

Power is what’s at stake. Whenever you look at these systems it’s not just about how the technology is structured, but it’s how we actually understand it holistically within the broader environment.

Take scheduling software. This is the software that determines who gets jobs at any given point. The reality is that you can actually design scheduling software to be about optimizing the experience for workers. I can promise you that’s not how it’s being deployed in major retail outlets. It’s being deployed in order to break unions by guaranteeing people don’t actually work with one another. In the United States it’s being deployed to make certain that people work no more than thirty-two hours so they don’t get health benefits, etc. It’s not about the algorithm, it’s about the process.

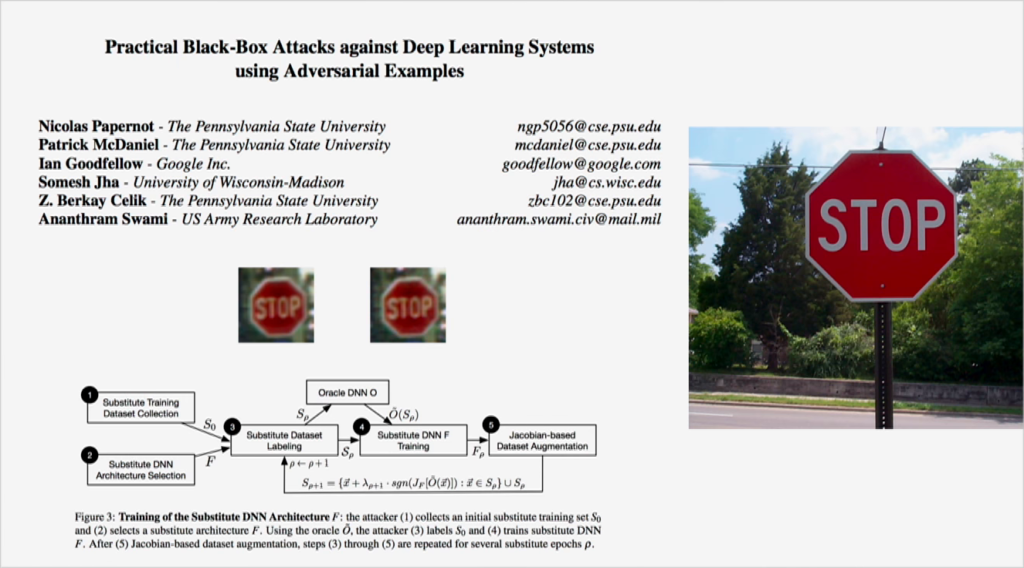

It’s also where we see new forms of manipulation. Because we talk about all the ways in which this data can get biased or things can go wrong. But it can also be exploited. This is right now in the world of experimental research but it’s fascinating for all of you are following autonomous vehicles. Nick Papernot and his colleagues have found ways of modifying stop signs so that autonomous vehicles believe them to be yield signs. Imagine this as a way of intervening massively.

Okay. So we’re coming to the end. I’ve given you this crazy tour through issues of bias, discrimination, ways in which context matters, the ways in which things get exploited. But how do we then think about accountability here? How do we think about responsibility? What of course matters the most has to do with power. But who is setting the agenda, under what terms, with what level of oversight? And who is hacking the system to achieve what agendas?

On both sides of the Atlantic there’s growing concern about the power of tech companies in shaping the information landscape. And I think this is pretty amazing to watch, especially here in Germany. There’s reasons that we’re watching this, because there’s a massive reconfiguration of the social contract and power dynamics in society, and a lot of that is incorporating through technology. But it’s not simply about the platforms. It’s about a set of new cultural logics which I like to think about through the frame of bureaucracy.

Because I would argue that today’s algorithmic systems are actually an extension of what we understand bureaucracy to be. And part of the decisionmaking processes is about the ways in which we can actually shift responsibility, moral responsibility, across a very complex system. And if we look about it as the ability to understand the making of cultural infrastructure, we start to see the way in which data is configured in ways of controlling a larger system. It also means that the mechanisms of accountability, the mechanisms of regulation, can’t look simply at an individual technology but they need to look at it within a broader set of ecosystems. We’ve spent the last hundred years obsessing about how to create accountability procedures around bureaucracy, but we haven’t figured out how to do this well within technology.

Let’s also acknowledge that the ability to regulate bureaucracy has not actually worked so well throughout history. And bureaucracy is something that has been systematically abused at different points. In 1963, Hannah Arendt controversially published her analysis of the Israeli trial of Adolf Eichmann. She described in excruciating detail how this mid-rank SS officer played a significant role in facilitating the Holocaust through his logistics processes.

But not because he actually was smart. In fact, he was really dumb. It was the way in which he became part of a military bureaucracy and believed himself to be following orders. And the way in which the distribution of responsibility could be something that would be exploited for a variety of people with negative agendas.

She of course famously subtitled her book “the banality of evil,” which is something I think that we should meditate on, especially over the next three days when we think about these technologies. How is it that it’s not necessarily their intentions but the structure and configuration that causes the pain?

And so from Kafka’s The Trial in 1914, to Arendt’s ideas of Nazi infrastructure, we’ve seen some of the dynamics of where bureaucracy can be mundanely awful to actually horribly abusive. And I would argue that the same algorithmic systems are introducing that wide range of challenges for us right now.

It also means that the roots of today’s problems are much deeper than how an algorithm prioritizes content, or maximizes towards a present goal. Just as adversarial actors are learning to construct and twist data voids, the new technologies we’re seeing are actually becoming a logical extension of neoliberal capitalism. The result is that we give people what they want, with little consideration to how individual interests, how financial interests, may end up resulting in undermining of social structures. Because what’s at stake is not within the bounds of that technology but the broader social configuration.

So I’m a big believer in Larry Lessig’s argument that systems are regulated by four forces: the market, the law, social norms, and architecture. And this is where this question of regulation comes into being. Because I’m confident you all will basically be pushing the directions regulating major tech platforms. But to what end? Are you purely looking to regulate the architecture of these systems, without disturbing the financial infrastructure that makes them possible? Or are you willing to dismantle the surveillance infrastructure that props up targeted advertising, even if it means that your politicians and other capitalist structures are going to lose their ability to meaningfully advertise to people?

Are you willing to dismantle the financialized capitalist infrastructure that pushes companies to hockey stick profits quarter over quarter? And what will you do to grapple with the cultural factors that manipulate these systems? What are you willing to do to make certain that prejudicial data doesn’t get amplified through them? Because what’s at stake is not just what we can set up legally in terms of a company, but how we can actually structure the right kinds of norms and cultural structures around it.

Fear and insecurity are on the rise both here and in the US. And technology is not the cause, technology is the amplifier. It’s mirroring and magnifying the good, bad, and the ugly of every aspect of this. And just as bureaucracy was manipulated to malicious purposes, we’re watching technology be a tool for both good and evil. What we’re fundamentally seeing is a new form of a social vulnerability, security vulnerability, sociotechnical vulnerability.

Fundamentally, what comes back over and over again is questions about power. And this is where I want to sort of leave you for the next couple of days to really think about things. Because stabilizing the ability to really grapple with an information war, an epistemological war, goes far beyond thinking about how to control or make sense of a particular technology. It requires us to think about all of the interfaces between technology and the news, technology and financial instruments, technology and optimizing for social interest, technology and our public good.

And frankly, I’m not actually sure how we meaningfully regulate these systems. Because what I know for sure? is that regulating the tech companies alone isn’t going to get us where we want. Thank you.