Eleanor Saitta: So yeah. I’m going to talk a little bit about this idea of performing states. And I’d like to start with kind of the typical introduction and talking about who I am and where I’m from.

This is who various states think I am. I have two passports and Finnish residency card. There’s a few other bits of state identity that we’ll get to in a little bit. And I’m going to spend a little bit of time digging into identity because I think it’s interesting to look at how the relationships we have with states shape the way we see states as constructs and as entities. And so I’m going to start with some old family photos because it’s kind of fun.

So, my father was born in Rome. His father was born in Sicily. His mother was actually born in the Uffizi in Florence, because that’s where the family office was. And they moved to New York during the war in ’43 or so.

Like many people, my dad ended up in a bunch of dead-end jobs, you know, like many war immigrants. A bunch of dead end jobs in Beth Page New York, living out in Long Island. So he joined the Air Force and he ended up working on nukes in Greece in the mid 60s, which is what eventually killed him. He got the GI Bill. He went to Cooper Union, became an architect.

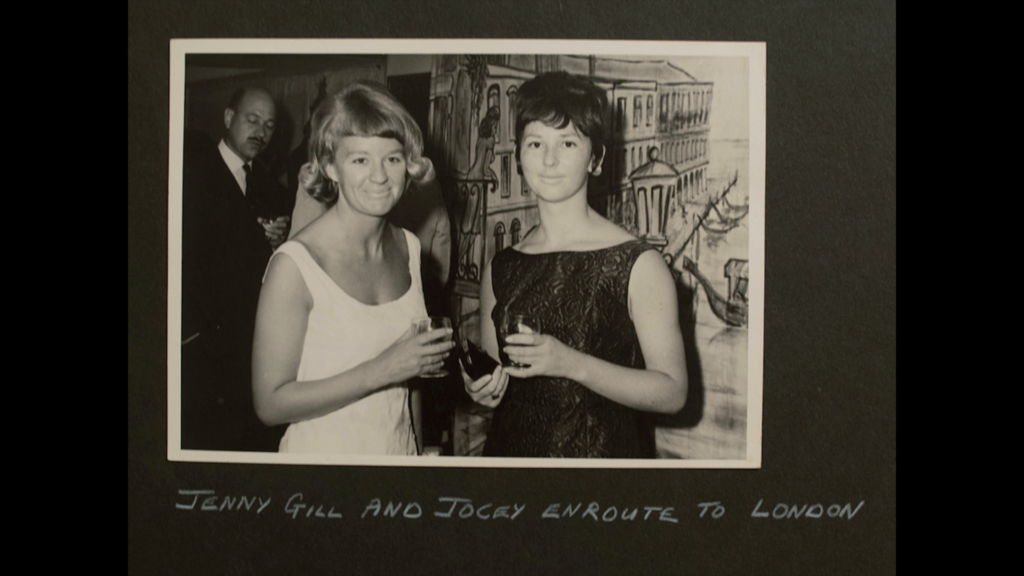

My mother was born in Melbourne. She was the daughter of a fairly well-connected academic. She worked summer jobs to buy passage to London, because Australia was tiny and if you wanted to do anything with your life you had to leave.

They both ended up in New York. They moved out to California and then they had me, because this was New York in the 1970s and it was no place to have a kid or really do much of anything unless you were spectacularly wealthy. (Some things have not changed very much.)

I grew up in California, but the California I grew up in was a California of two people who were yes, immigrants, but not immigrants within the American narrative of “this is America the land of opportunity” etc. It was “this is America, it was convenient.” I remember being told explicitly when I was fairly small growing up, “We’re not from here. We’re not like those people.” Which is probably not a thing you should ever tell a child. Please don’t tell your children that, even if you believe it.

But it left me with a very interesting relationship with this place which was becoming a real seat of power around the world. And we’ll talk about that a little bit later.

So I grew up, and I went to school and failed out of school, and ended up drifting into Seattle, and drifting into doing security work. And got bored with Seattle because it was a land of absolutely no culture except a lovely music scene. And ended up moving to New York, as people are wont to do.

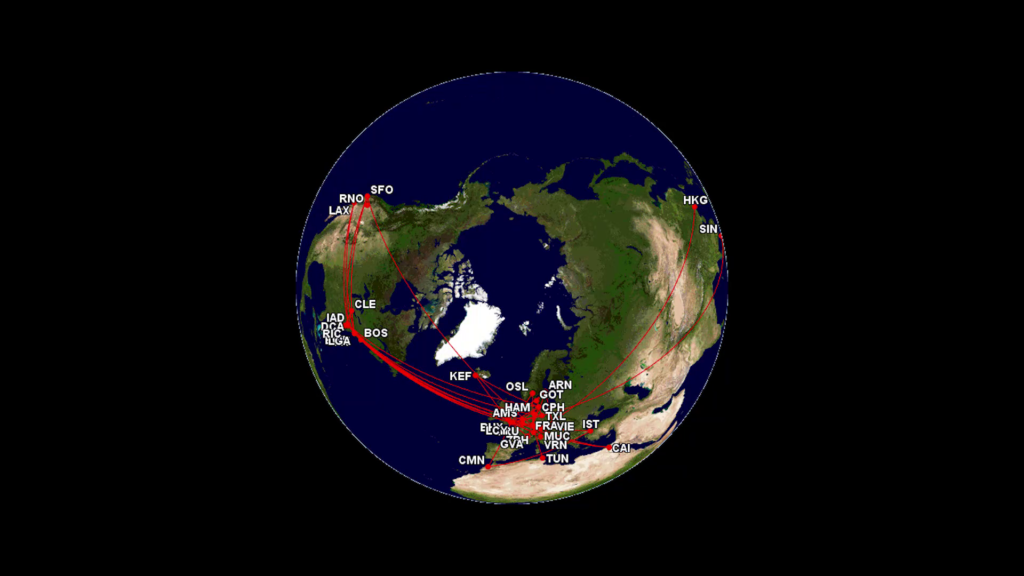

There’s a bit at the end of the move where you’re supposed to stop. And I kind of forgot to do that. So this was my 2013, or part of my 2013. And I spent seven or eight years traveling full-time. That year, I think—I think it was that year, I was moving about thirty kilometers an hour for the year.

I was doing it for a lot of different reasons, partially because I kind of fell into doing NGO work and and security support for NGOs ands news organizations. But partially because I realized that when I was in the US as someone who had grown up there, I couldn’t see the rest of the world. And this is something which I think is probably not uncommon as an experience for people who live in empires? But it is very difficult to get any perspective of what anything else in the world means. Previously to the American empire, I don’t know that we’ve really noticed that lack of perspective because we’ve…the assumption has been that you see the world from the perspective of where you are. The assumption has not been that you live on the Internet and see the world from the perspective of everyone you know everywhere else around the world. But I found that while I was living there, I didn’t understand the stories, and as soon as I left the country they started making sense again.

How many people here have read Kyle Chayka’s piece “Airspace?” I recommend looking it up. It’s a great little essay. He’s basically talking about this idea that there is an aesthetic which has become…both accidentally and intentionally universal in certain kinds of spaces. I used to joke with friends that I lived in one neighborhood that just had really really shitty public transit, you know, and it would take twelve hours on the bus to get from the Prenzlauer Berg part of the neighborhood to the Soho part of the neighborhood.

And this is kind of what he was getting at with airspace, although I hope I lived in a slightly more genuine world. This idea that even outside this bubble of empire that stretches across military bases and various things, there is another layer of space that a portion of humanity moves through that is the kind of distressed wood that you see in cafes. That you see the same table, or you know, the local reproduction within the equivalent aesthetic of the same table, in cafes just about everywhere that are targeting the same kind of person.

One of the things I learned when I was traveling, and I think it was… It took me a while to really understand what it meant to not live anywhere. There’s this idea that like oh, it’s just traveling; oh, I’d love to go traveling. And then you realize that okay like, there’s all these problems of like, well I don’t have a fixed address, you know. Like all of these things of what it means to be…possibly not homeless in the structure of privilege that that implies, but you still have all of the same legal issues. And one of the things that I learned from other friends who traveled in very different ways is that the equivalent thing to asking a settled friend “Where do you live?” Like, “what kind of neighborhood do you live in? Is it a rich neighborhood? Is it a poor neighborhood? Do you live in a house? Do you live in an apartment?” is, “How fast do you move?” or, “How frequently do you move?”

So for 2013 my goal for the year was to get my average time per city up to a week a city, which I did not succeed at. I think I was about four and a half days. But I had other friends who also traveled full-time, but they changed cities once a month. And they maybe moved by train instead of by plane. Or they lived out of a van and drove around the country.

And in many cases this was a class distinction but in a lot of them not. One of my coworkers at the first security job that I worked at, and a research partner still to this day, lived in a van for the better part of a decade. She decided she wanted to leave Seattle at some point and bought a van to drive around the country to figure out where she wanted to live next. And she realized that she really liked living in a van. So she did. And that experience was another thing that really shaped the way I kind of saw the country and saw countries as a category.

When asked where I was from…which is, you know, one of the first things that you get asked, I used to say I was from the Internet. Which started out as as a funny joke and at various times became more and less bitter. And obviously when I’m outside of the US I read as American. But one of the interesting experiences and one of the things that really kind of led me to start saying that fairly seriously is that when I was inside the US I didn’t really feel like an American—I didn’t really understand what this country that I was supposedly from meant.

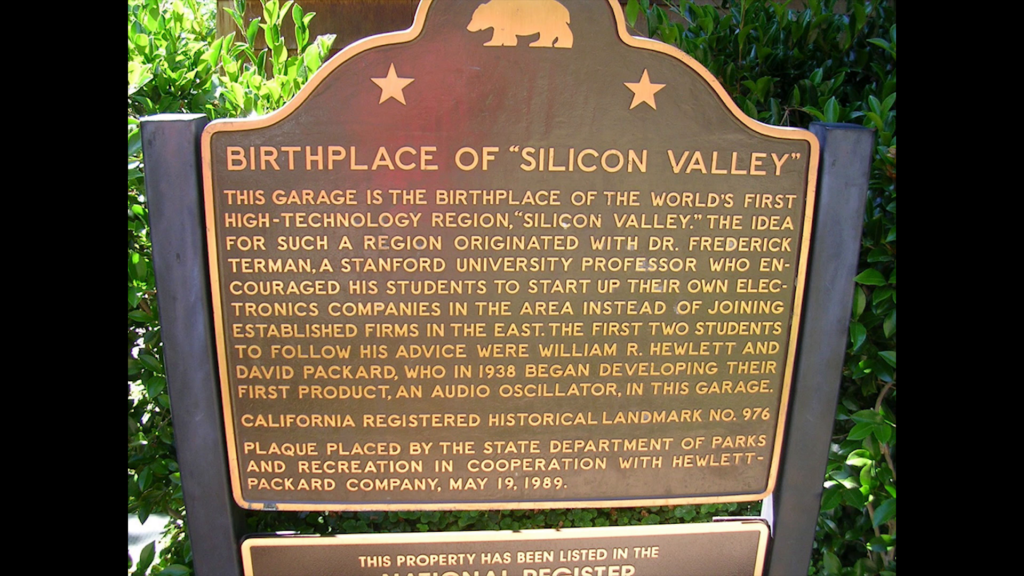

And also there are ways in which I was fairly literally from the Internet. I maybe don’t know what it means to be American but I do understand what it means to be a Californian. I don’t know how many of you are familiar with the history of the Bay Area. It is a very fascinating place which is full of toxic waste dumps because when the first people building Internet systems and computer systems there started doing manufacturing, they really didn’t understand safety regulations or they just didn’t care. So, you get these kinds of plaques which is the sort of heroism of oh, this is Silicon Valley, this is all that. And you also have more Superfund sites per hundred square miles than anywhere else in the country by a fair bit. And I think that that is really an entirely just summary of the area, of having both of those sides. Although I’m starting to question the heroism.

One of the things that we’ve been hearing lately is people pushing to rename… “Oh, we shouldn’t call it Silicon Valley, we should call Surveillance Valley. We should be more honest about what it is.” And as my friend Ingrid was saying the other day I mean, yes you could do that, but really the silicon is important too, guys. Let’s not forget about the toxic waste dumps.

The Internet I’m from is dead. And this was kind of a startling thing to realize a few years ago. Well, really, a few months ago fully. That the place that I identified with doesn’t exist and has been replaced with something else which is much bigger, and much more aggressive, and in some ways much more hostile but mostly just much more unpredictable.

Now, obviously we’ve been talking about the death of the Internet for a very very long time. This is a piece from 1995 where Clifford Stoll was predicting the death of the Internet. So it’s been a popular hobby.

But I want to talk about this idea from a friend of mine, Quinn Norton, called the invisible city. If you look at the history of urbanization, it took us about 140 years to move something like half of the world’s population from rural villages to the city. And for most of that period, a lot of people were basically doing the equivalent of walking out into the street and getting immediately pasted by a tram. Because they had really no idea how to live in the city. And it took us a very long time—and you know, we had a head start on this; this is something that’s been going on for longer—to learn what it means to live in a city.

So, civic inattention, right. You’re sitting in a coffee shop and someone at the table next to you is talking about who they slept with last night. Except it’s not a very interesting story. It’s not a story that you’re gonna listen to just because oh, it’s really fun and it’s engaging. No, it’s actually just really boring. So you ignore them. Because, why wouldn’t you? That was not something that came naturally to us as a species. We had to learn that oh yeah, that’s boring. They are not part of your social world…who cares? And this is something that… You know, you can you can go back in the archives and find people who talked about this and talked about this as an explicit thing that you had to learn how to do. The country bumpkins who showed up and didn’t get it for quite a while.

We have now in twenty years moved half the world’s population, give or take—two billion people anyways, solidly—to one city. And we all live in one city. And we keep walking out into the street and getting pasted by trams. And we don’t even understand what the trams are. We not only do not know how to live together online, we don’t even really understand that it’s a problem. We don’t even really see this.

And then some days you wake up and you notice “Oh. Jesus. That’s a tram and it’s in my bedroom.” Which happened to my friend Quinn the other day when eight million people decided she was a Nazi sympathizer. Which is a really shitty way to start your morning, let me tell you.

So I guess now I’m from here. But what I want to talk about is social script. When we talk about learning how to not get hit by trans, on the Internet what we’re talking about is how to be human, how to perform human in a city, how to perform interaction with each other.

And those are really important, and they’re really useful, and they’re really interesting when we start talking about borders. How many people here have crossed a hostile border? Yeah. It’s a fair number. I remember the first time I was… This was kind of just at the start of when I was traveling. And I was flying into the UK. And I’d basically been wandering around Europe for six weeks with a backpack, and I was super sleep-deprived. And I show up at the English border being like, “Yeah I’m here for like maybe ten days. I don’t know…” This did not go well. They were very not pleased to see a super sleep-deprived, possibly slightly hungover American showing up with a backpack and no particularly clear travel plans.

And fortunately I did have like three different credit cards with the name that matched my passport, so they eventually let me through. But that ability to at least pretend privilege, right, whether or not you are actually of the privileged traveling class or not. The ability to perform privilege at a border, right—and it is a performance, you know. That performance is something that anyone who travels in complicated contexts learns. And everyone around them learns it, too. And I don’t know like… I’m assuming that most of you have EU passports, so you probably do not have the experience of being at the “all other passports” line and being like okay, there’s four all other passports lines, and I have twenty minutes to make my flight. And you look ahead at who’s in front of you. And you do all of the same racial stereotyping that you think the border guards are going to do. And then you look at how much paperwork they’re carrying. And anybody who’s carrying too much paperwork, you get in a different line. Because they’re gonna have a very complicated conversation with the border guard. Although last time I crossed in there was a very rich-looking American gentleman in front of me who really didn’t understand that no, I’m sorry sir. I don’t care if you’re a Swedish double citizen. You can’t enter Sweden indefinitely without a Swedish passport. You need to actually have the passport. He didn’t seem to understand this.

But we end up doing that kind of both modulating our own performance; looking at how we perform; choose to perform privilege; when it’s accessible to us; if it’s not accessible to us then we work around it in other ways. And we watch the performances of other people around us when they’re going to affect us.

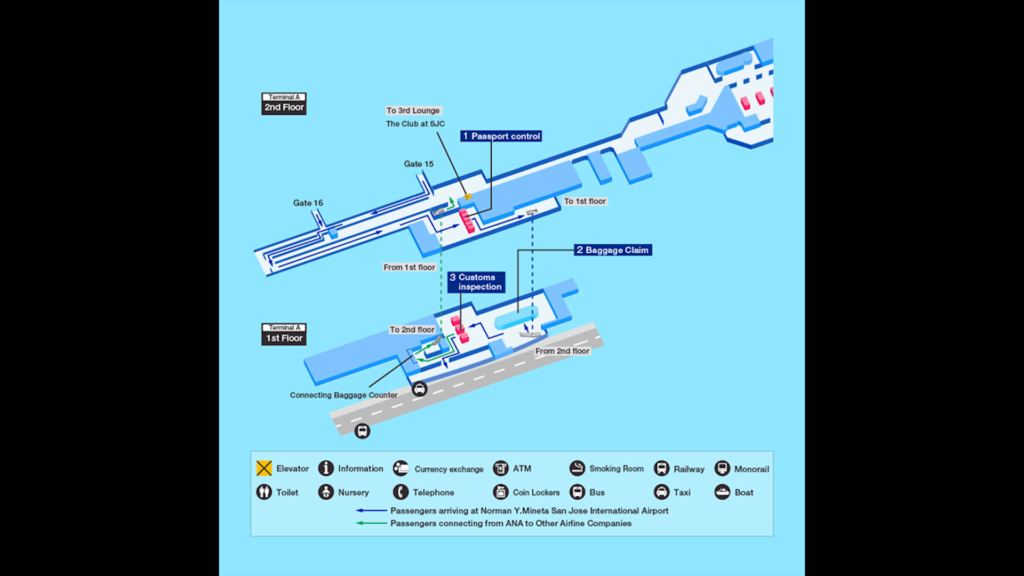

This by the way is something that I find really amusing. I could not find a photo of the exact spot or even a map of the exact spot that I’m thinking of. In Dublin airport—and I think I’ve seen this in Reykjavik and a couple of other smaller international airports. It’s a one-level airport. So you get the corridor coming in from the gate, and you get the corridor that goes off to immigration. And there’s this box where there’s doors on four sides. They’re automatic doors. In at least the Dublin case, there’s a patch of ground where it’s got kind of motion sensors on the two feeding-in corridors and a timer. When the timer expires, it closes one set of doors, waits till it detects the patch of ground is empty, opens the other set of doors. So this chunk of ground is shared. This chunk functionally is part of two corridors so that people can get on to the plane and people can move along the route to passport control.

Now this means that you’ve got a robot moving a patch of ground between nationalities. Because when I’ve boarded there it’s been international passengers coming in, and Schengen flights going out. So this patch of ground has a robot moving it in and out of the Schengen region.

And I always find the physical performance of… Like the literally physical performance of moving through that kind of border space to be really interesting. Especially these days as it’s gotten messier and more complicated, when I’m leaving the US there’s always this kind of physical sense of release. Of like, okay, I’m no longer… You know, I’ve made it through passport control. I’m on the other side. I’m not necessarily in a country yet, you know. Maybe I’ve cleared— I’m just—I’m in international transit. I’m still not anywhere but I’m also not in the US. And that kind of limbo space is something that I find really interesting.

Back to those social scripts. I want to talk about them a little bit. And what I want to talk about is live action role playing. Now this is gonna sound completely ridiculous, but bear with me for a little bit. When I talk about live action role playing some of you will have no idea what I’m talking about, and some of you will have a mental image of a bunch of people running around in the woods with foam swords pretending to be elves and orcs and beating each other over the head. That is what I’m talking about, but I’m specifically talking about where larp went in the Nordics. If you’re interested in why I think it went there, ask me later and we’ll get drinks.

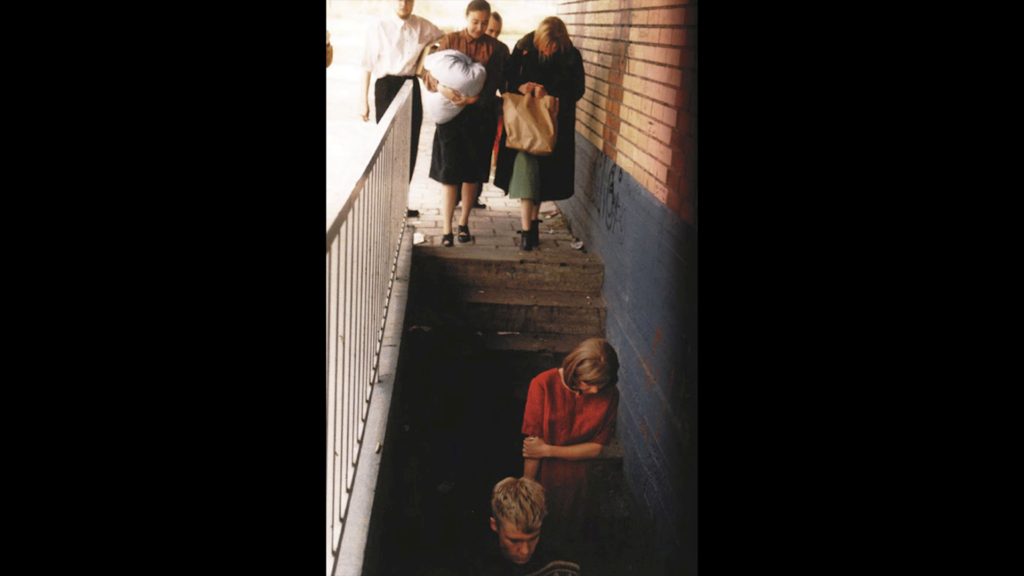

But this is a photo from a game called Ground Zero which I often use as an introduction. Ground Zero was first played in 1998. It was a game for about twenty-five players. It was set in Topeka, Kansas in 1962. It’s a Finnish game; it was played in Turku. And the week before the game, they got together and had a dinner party in character. You know, kind of listened to music of the era, understood what their social relationships were, and it was just kind of a normal dinner.

When the game started, they all went down into the basement of a rec center that had been redone as a bomb shelter. And here they are kind of trooping down into the into the basement in character. And the game was set during the Cuban Missile Crisis. So there’s an in-game game radio which is playing historical radio pieces. And the situation outside gets worse and worse. And at some point it changed over into fictionalized recordings. And at some point, there’s a burst of static and the radio goes dead because New York has just been nuked. And then the power cuts out.

And then about forty minutes later, there is a massive earth-shattering boom. Because what they thought was a wall full of cardboard boxes of canned goods was actually a wall full of speakers. I think they actually blew out about a third of the speakers in the wall because they had the amps turned up too high. And that’s it. Then they sit in the dark for the next twenty-two hours and try and understand what it means for everyone they know to be dead.

The game ends the next morning. The organizers basically rip open a door and say okay, it’s over. And they tell people the shelter cracked, water leaked in. Over the next three or four weeks half of you died of cancer. We’re not telling whom. End.

And it was a fairly emotionally powerful experience, especially for folks who were of the generation that was very aware of the Cold War. This was this was a less distant memory then it certainly would be for folks their age now. And it was incredibly emotionally moving, you know, the kind of political message that was part of what they were talking about was really very strong.

This is my friend [Jok?], and she’s talking about designable surface—Johanna Koljonen—and she’s a Swedish media writer among other things. And this is kind of one of the most key ideas, right. You have a game, you want to change people’s understanding of the world. One of the biggest things you need to do then is to shape their behavior, and to shape their understanding of the meaning of social interaction. So we used designable surface to do this, right. And this is something that we think about in other contexts. If you’ve dealt with systems design or service design as a discipline, as it’s kind of developing, you think about touchpoints, that kind of thing. But surface design is looking at a much broader set of all possible interactions with the system that end up shaping emotional experience and emotional meaning, much more than than just kind of this oh yeah, that sign explains how I interact with this box.

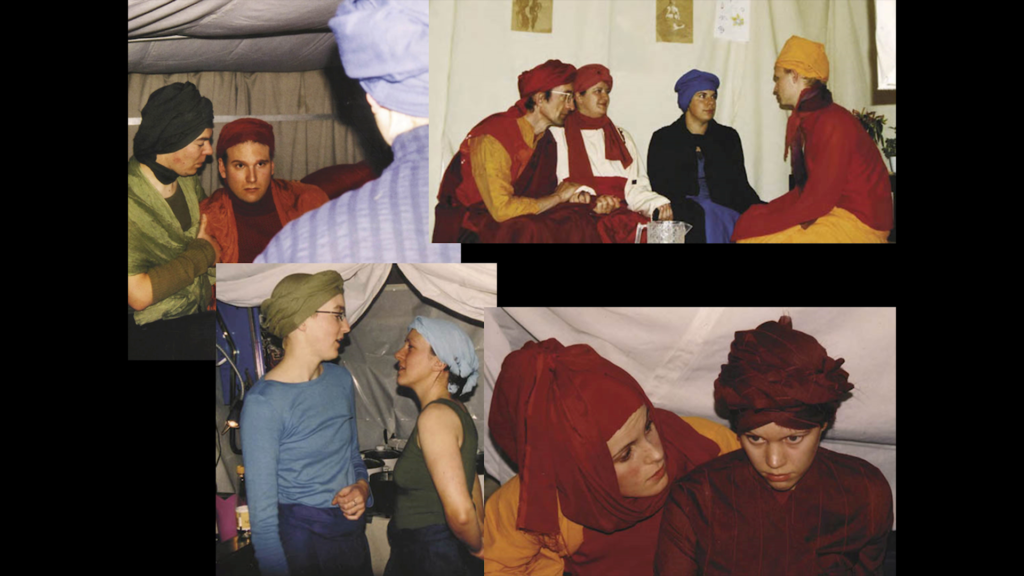

You can rewrite social scripts fairly extensively if you use your designable surface well. This is a game called Mellan himmel och hav, Between Heaven and Sea. It was an Ursula Le Guin-themed fiction. This was run in 2003. It was an explicitly happy narrative. It was a tale of a community on a world that has a very long season cycle. And spring is returning, and the community is preparing for a marriage. And it’s a fairly small community so this is a big deal.

But everyone in the community is sorted— Marriages are all four people. And the performed genders are not male and female. Although those exist that’s a medical issue, basically. There are morning people and evening people. So morning people are the practical ones. They get up early, they build infrastructure. They manage the tasks of the community. Evening people stay up late into the night talking about politics. You know, it’s ridiculous to think that an evening person is going to get anything done, practically, because they’re not up when the work happens. Just like it’s ridiculous to think that a morning person is going to be politically-involved.

So every every marriage has two morning people and two evening people, and that’s kind of the structure. And, as you can see—these are these are all in-game photos—they had six days of workshops beforehand. And a lot of really intensive work went into kind of stripping away and then rebuilding people’s understanding of gender identity and gender role and gender performance.

And this had some really lasting effects. You know, there are a number of people whose actual gender identities shifted because of what the game let them experience and they understood themselves to be a different person. Not because the game brainwashed them or anything but because it gave them a space for exploration. They were also living in extremely close quarters in the game. Six folks I know ended up sharing a fairly small like thirty-five square meter one-bedroom apartment for three or four years after the game. Because they realized that if they did that they could live in central Stockholm and basically not pay rent. And the game had taught them both some specific techniques for how to functionally live in that kind of space, but also had shown them that they could build scripts that were actually that aggressive in terms of rewriting their lives.

Now doing this in reality is often harder, change is slower, consent is a lot more complex. The tools you can use are more restricted. But social script design can work in interesting ways.

So let’s get back to borders. What a border is is changing, and it’s changing fairly rapidly. This is what the US government designates as the border zone. This is the region of the US, which includes about 90-something percent of the American population, that customs and border control considers to be within scope of their operations. So anything that they can do when you come through customs at JFK, they can do anywhere in the border zone. Including everyone in Hawaii. You can’t get away from the border in Hawaii.

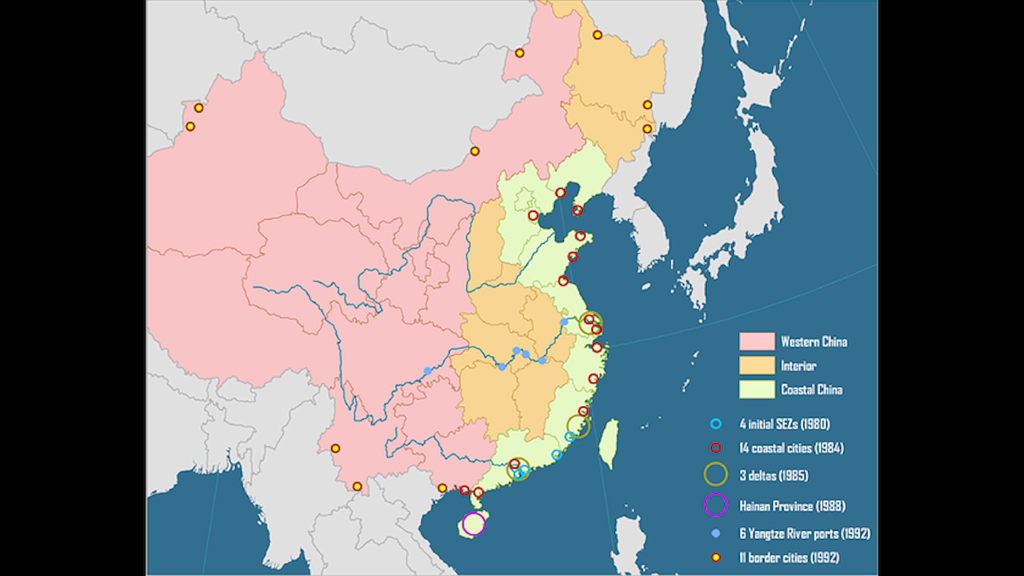

We also have special economic zones. When I was putting this together I actually went to see like oh, special economic zones. Those are like, fairly complex pieces of government bureaucracy. Surely there must be a fairly—you know like, there must be a list, right? And somebody must have compiled a map of all of the special economic zones in the world.

Nope.

There were maybe about 10,000 of them. Ish. We know where… Someone knows where all of them are. But they are in many countries fairly intentionally opaque. A special economic zone, for those not familiar with the term, is a designated region of a country which is not necessarily part of the country’s soil for certain purposes, generally including tariffs, trade regulations, and labor regulations—labor laws. And often including a really pretty extensive set of stuff. This is the set of Chinese special economic zones. Many of those are cities or entire provinces, so these these aren’t necessarily like, small patches of ground but like a free port, which might be a few warehouses at an airport which is outside of the country for customs purposes. It’s kind of on the same continuum. Free ports are where probably…if I had to guess, probably at this point maybe a third or half of the world’s art is stored out of public view. Just because it’s being bought for investment purposes and they don’t want to declare customs on it anywhere because that’s expensive and makes it less useful as an investment vehicle.

We also have networks of control that tie into a lot of these things. This is Guiyang’s shiny new CCTV control center that they showed off to the BBC a few weeks ago. The appearance of this center, like, does it need to be this kind of massive room with all of these very shiny desks for the purposes of what’s going on there? No. But it’s a very useful designable surface for the state to shape the social scripts of response to CCTV. This is one of the CCTV centers where all the cameras in the city are hooked up to a face rec system. And so they took a photo of some BBC reporter, had him get dropped off somewhere random in the city, start walking around, and they found him in seven minutes. Now, we can also talk about false positives and you all of the other issues with systems like this, even ignoring the minor human rights problems. But as a structure of control which is being rolled it’s an interesting data point.

Here’s a Western example, very tight geolocation indoors. This is deployed in a lot of malls in richer Western countries, where it’s not legislated against. So they pick up the WiFi radio in your phone, and Bluetooth if you’ve got it on. Cross-reference that against say, the MAC address that the Facebook app has exfiltrated out. You know, there’ll be a data broker that’ll kind of bring all these things together, so that then they can say, push ads to you for things that you might’ve seen in stores that you spent a bunch of time lingering in.

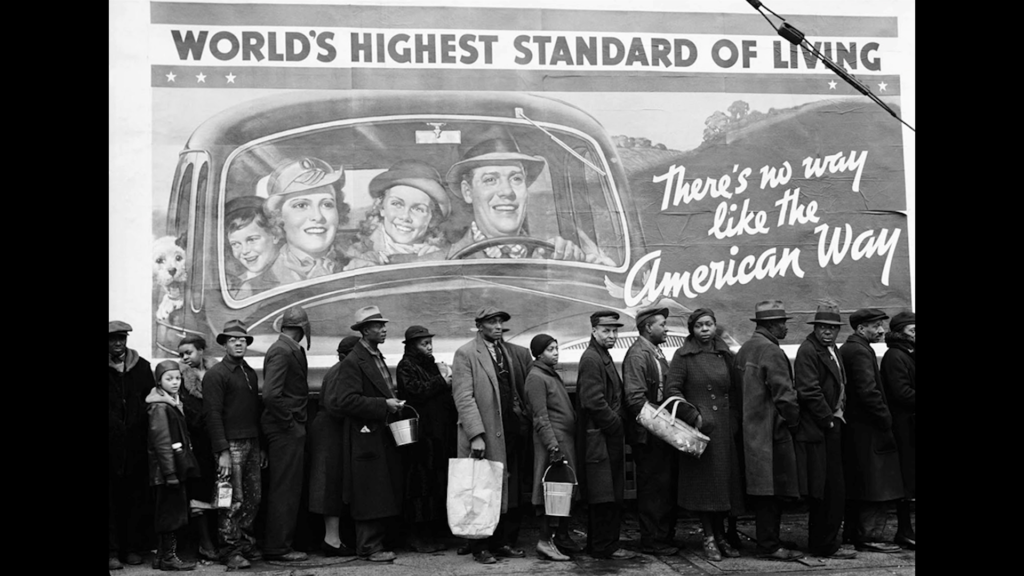

So why do we actually need a physical border? Like it’s clearly… Like, you know, the future is not evenly distributed, whatever whatever, but like it’s clearly kind of irrelevant. So a nation is infrastructure for someone’s standard of living. Probably not your standard of living.

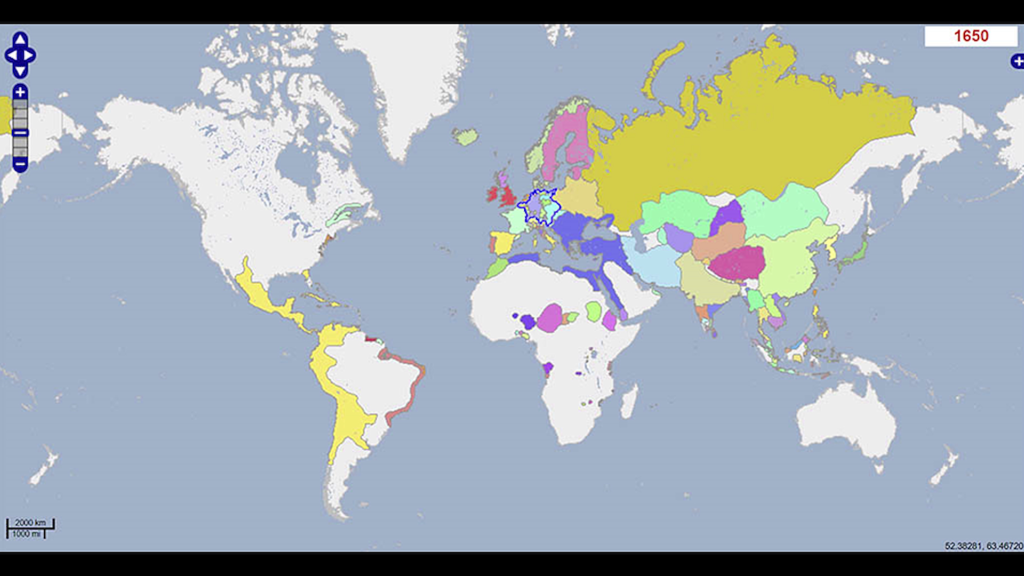

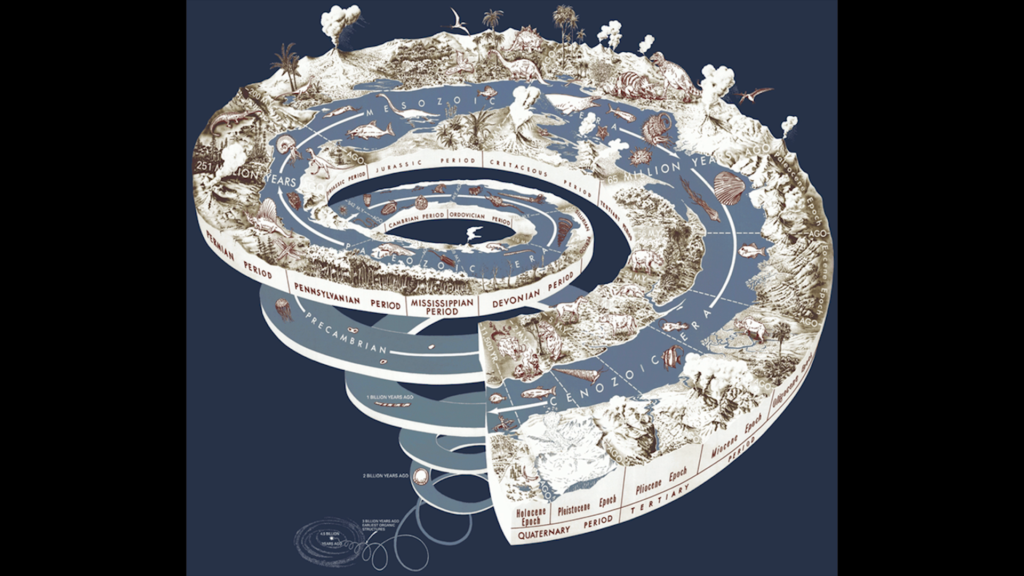

This is a a map from 1650 of places that were considered nations by…whoever compiled this map. And so the modern nation project co-rose with industrial infrastructure. And I don’t think that’s a coincidence.

So you’ve got you know, a bit more in 1850; the colonial powers have started expanding. And then all of a sudden, 1900, almost total. 1940, there are no more gray areas on the map.

Now this is a hilariously terrible map. It does not recognize any indigenous populations that might consider themselves to have been a nation. Also, many of these things, certainly in 1940, were states by name but not states in any functional way. But what they care about here, what the people who compiled this map care about are nations that are signified and legible to the collective project of nationificacation, which was a…you know, again, you can read the receipts. There was a very aggressive, careful project to ensure that land was not left outside of the system of nations, because for the purposes for which nations were being constructed, they needed the system to be as total as possible. States of exception were…states of leakage—they were weaknesses.

Now, we can look at multiple things that we might call nations or peoples or that kind of thing. We can look at shared cultural identity. And many, some, of these states have shared cultural identities. Some of them even had shared cultural identities before someone drew a line on a map. We can look at the kind of signified nation view that this actually represents. But what they actually are is geographically-bounded coercive infrastructural collectives, right. This is a chunk of land where people are building infrastructure. It is one pool of infrastructure. And you don’t get the choice of opting out of that pool of infrastructure. Because it’s not possible to build industrial-scale infrastructure unless it is a coercive collective project. We can debate the coercive bit, but certainly given the political tools that people had at the time they didn’t know how else to do it.

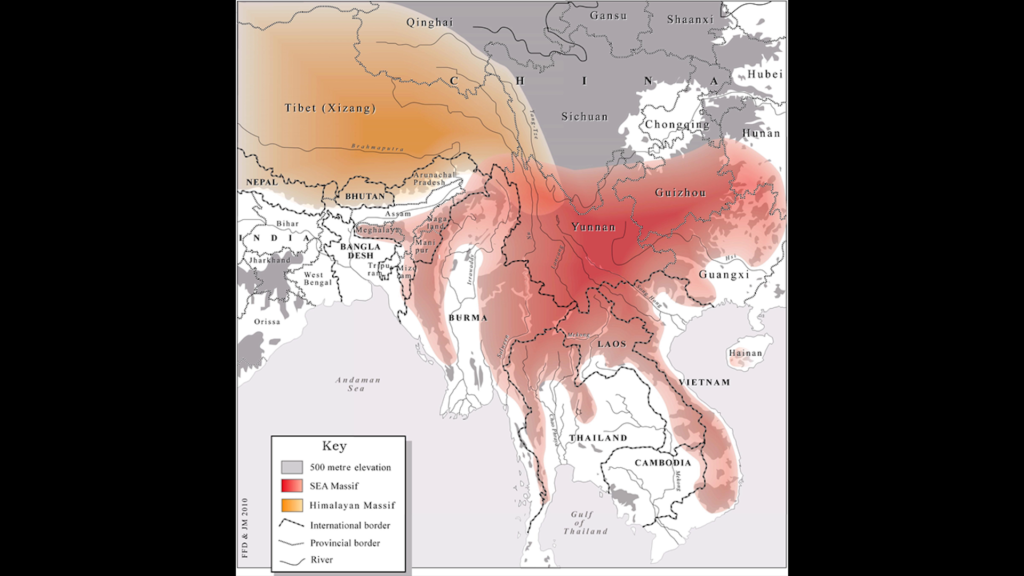

Who here has read The Art of Not Being Governed? James C. Scott? Okay, a few. So The Art of Not Being Governed is an explanation of the politics of Zomia, which is this bit of Southeast Asia, or specifically the parts of Southeast Asia that are too far above sea level to grow rice. Because historically, states in that region were connected to rice growing. And one of the really interesting things about that history is that it’s not the narrative that we traditionally hear of like, states expand and bring people into their fold, and that kind of thing. It went both ways. You had a lot of people being like, “Hmm. This state isn’t working out so well for me. I think I’ll leave. I’ll go up into the hills and become a non-state person for some period of time, until maybe conditions get better.” And all of that stuff about shared cultural identity, that all changed. That all changed, and changed actually quite rapidly, in line with these collective movements.

One of the things which ended up being very useful, by the way, were sweet potatoes. They’re great. You put them in the ground. They grow. You can’t take them with you, they’re too heavy. You can’t steal them, they’re not expropriatable by a state. You leave them in the ground for two years—they’re still there. And it’s interesting when we’ve talked about shifting borders, if we think about you know, how climate change may shift the rice-cultivatable areas in that region, we may get the stateable areas there—at least in the traditional definition of what states have been in that region—shifting just based on biome shifting. Now, of course modern technology has changed what is stateable in those places.

Production has become global. This is part of a fairly simple supply chain map for a laptop. It’s very very simplified. But if we want to survive climate change, we need to see not just production, not just the supply chain side, but all of the infrastructure projects have to be conceived of in terms of global scope, right. Because they have a global impact.

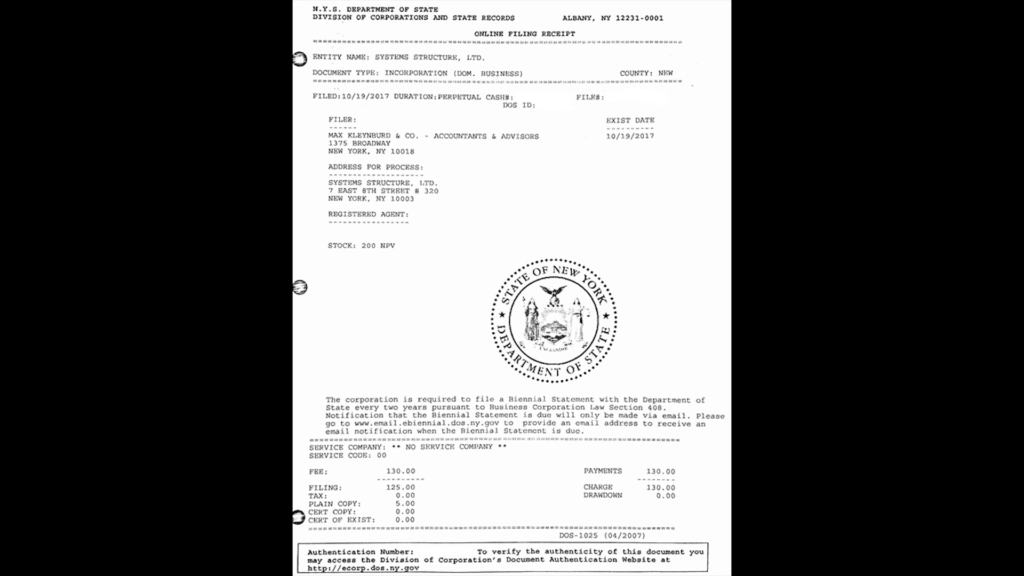

I have one more family photo which significantly changed my relationship with the US. Just before I left I became a full US citizen, which is to say a corporation. Which was a really weird experience because it really does put you in a completely different mode of interacting both with the US and with most other states. Part of that capital flow, in some ways. So there’s part of me that can move around much more freely than the physical body can.

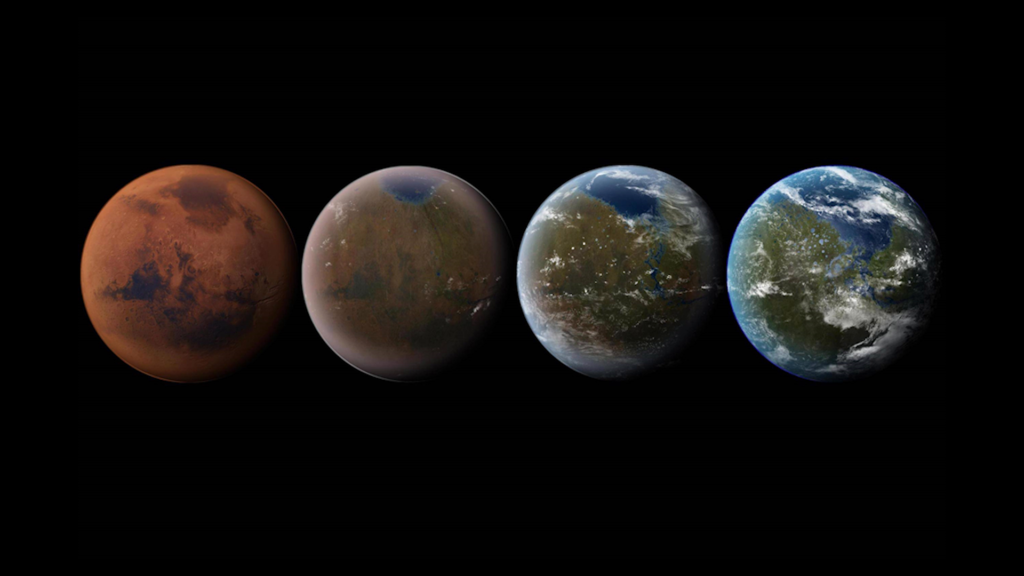

We are in a moment of choice as a species. If we are going to survive the next hundred years—eh…let’s be more realistic: the next sixty years, with what we currently see as globally-organized industrial civilization intact and functioning, we need to terraform this planet. Now, the good news is this is the easiest planet to terraform that we’re ever going to interact with. If you look at the kind of reasonable midline scenarios, we’ve passed two degrees Celsius. And if you look at the reasonable impact estimates for what that means…we’re not keeping industrial organized global civilization after two degrees. So, if we want it back, if we want to have our future back, we need to start terraforming. We have lost the ability to be local, right. This idea that we can only act locally, whatever, that we can live in a place and see ourselves as just people who live in that place, that’s gone. We now get to learn what it means to be a global species.

What this requires of us is that our infrastructural collectivity, you know, that geographically-coercive, geographically-bounded infrastructural collective, that thing that we made the nation to do, that has to get broken up. We have to unbound all of those infrastructural collectives. Because if we don’t, we will build infrastructure that does not work for the planet. This is not optional; we do that or we die.

We also need to flatten wealth inequality. And we need to do that not because the megarich are killing the planet and should be murdered. Although they are, and they possibly should be. But we need to do that because everyone in India wants a car, and an air conditioner, and a fridge, and that is entirely fucking reasonable. And if we would like to stop them, our options are…kill them, or figure out a way to give those things to them. And we’re going to pick one of those things and start doing that. And we will not psychically survive, we will not culturally survive, killing most of the world, and we probably shouldn’t try. So therefore we should probably figure out how to both flatten what we take and also provide that infrastructure in a way that is actually functional for everyone.

Now, all of this means that the thing that we built the nation to do we don’t need anymore. As you may have noticed, things that have become unnecessary in political terms do not just go away. But let’s think in slightly deeper time, right. Modern nations are about 400 years old. The era of total nationhood is maybe eighty years old. We live in a transient moment of total nations. This will pass. One of the things that I think we can do that is possibly one of the more important things that we can do right now is to figure out how to prehearse an understanding of what it means to exist beyond the total nation. And by prehearse I mean play. You know. That’s how we understand, that’s how we learn about things that are unknown to us, right. Later on we figure out oh okay, you can go to a classroom, you can recite these canned facts—that doesn’t help when you don’t understand a thing and there’s no one to teach you. So we need to prehearse our way into a future. Thank you.

Further Reference

Transnationalisms: Borders, Bodies, and Technology event page