Of course we’re avid, avid watchers of Tucker Carlson. But insofar as he’s like the shit filter, which is that if things make it as far as Tucker Carlson, then they probably have much more like…stuff that we can look at online. And so sometimes he’ll start talking about something and we don’t really understand where it came from and then when we go back online we can find that there’s quite a bit of discourse about “wouldn’t it be funny if people believed this about antifa.”

Archive

What I’m going to do today is situate digital methods as an approach, as an outlook, in the history of Internet-related research. I’d like to divide up the history of Internet research largely into three eras, the first being where we thought of the Web as a kind of cyberspace.

I think those of us who study and think about mis- and disinformation, it’s very tempting to study what’s in front of us. And so there’s a disproportionate focus on Twitter, because it’s the easiest to study because there’s an open API—although, caveats—and Facebook. That’s a lot of the places that we study. And similarly, that’s a lot of the places that journalists look for content and sources and stories. And so we end up kind of really just thinking about that as the “problem,” when actually we need to think about the full ecosystem.

Otherwise engaged refers to our time as a time of distraction. As a time when social media is actually beginning to focus our attention on things that are distracting. And I want to talk a little bit about first of all of our new—and it’s going to sound like an oxymoron, but it’s our new sort of distracted modes of engagement.

Lo and behold humanity is fairly consistent. We would mention mornings in the mornings. We get tired sort of towards the evenings. Talk about coffee more frequently in the morning. These are the sort of normal diurnal patterns that we see on Twitter, right. As expected. But when interesting events happen and events that are out of the ordinary happen it’s very clear that they happen.

I’m here to tell you little bit about a few examples of truthy memes that we’ve uncovered with the system that we have online. It’s a web site where we track memes coming out of Twitter and we try to see if we could spot some signatures based on the networks of who retweets what, basically, and who mentions whom.

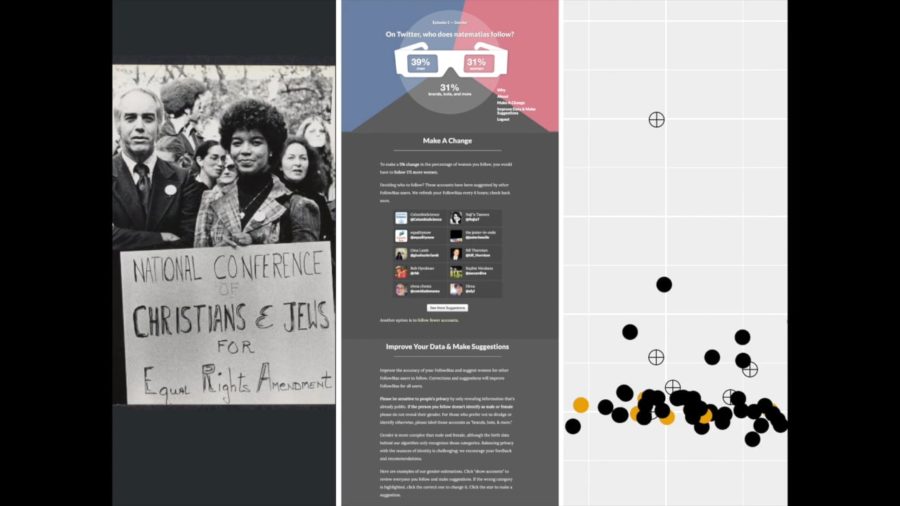

In 2011, the cultural critic Emily Nussbaum reflected on the flowering of online feminism through new publications, social media conversations, and digital organizing. But Nussbaum worried, even if you can expand the supply of who’s writing, will that actually change the influence of women’s voices in society? What if online feminism was just an echo chamber?

When I asked my peers and my professors if they’d ever heard of this type of work, two things happened. The first thing is that they said no, they hadn’t. The second thing they said, which is probably what you’re thinking, is, “Well, can’t computers do that?” And in fact the answer to that is no.

One of the things that was happening at the time is that one of the accusations that was being made, or that was being proffered by people who made sort of snap, knee-jerk responses to what was going on is that social media is being blamed. Social media was blamed for the worst civil unrest that England had seen in recent years.