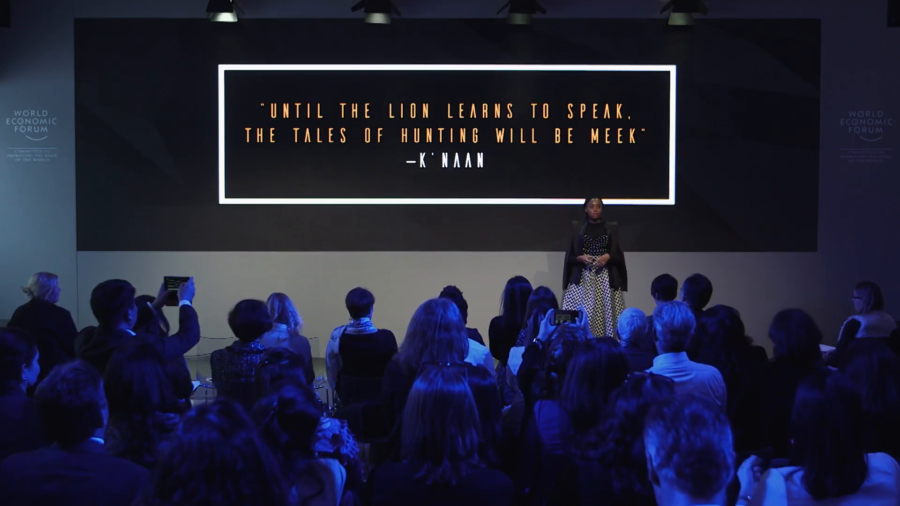

Wanuri Kahiu: So, there is a hip hop artist called K’naan. He is a Somali Canadian hip hop artist rapper. But he remixed an African proverb in which he said, “Until the lions learn to speak, the tales of hunting will be meek.”

So I recently traveled to foreign, and I was asked to present my film Pumzi, a short science fiction film. And when I got to the customs desk, I’m always asked for my paperwork, I’m always a random check. And I’m always ready. I have my return ticket, my hotel accommodation, my invite letter—everything I need to prove that I do not intend to stay.

So the customs officer asked me why I was there and I explained. She asked me what my film was about and I said it’s a futuristic science fiction film about Africa. And then she asked, “Why is it so important?” Why is it important enough for you to travel and discuss. To her, science fiction is obviously not important. And I couldn’t blame her for her awkward question. She wasn’t used to lions speaking.

To have the hunter tell it, Africa is full of meek stories about desperation and despair. So when artists like myself offer an alternate vision, often we’re asked to defend our imagination. Why do we feel we have the luxury to create? Shouldn’t we be dealing with more important issues like corruption, or war, or AIDS, or poverty? And I think this is largely because most people like to think of Africa only as the sum of its problems. And the problem with this is that it’s created a single story, that has created only one perspective of Africa, which we have allowed to tell about ourselves. We’ve allowed these stories to be told about ourselves as if they’re the only perspective on Africa.

So, the problem with that is that if the only stories about us are desperate and hopeless and lost then how can we for ourselves imagine anything better than that? So, as a result we created Afrobubblegum. And Afrobubblegum is an online platform that celebrates Afrobubblegum work, which is fun, fierce, and frivolous African art. It has no agenda. It has no policy. It’s not trying to save everyone or anyone. It’s not trying to do anything. It’s not trying to…it’s really just a celebration of art for art’s sake.

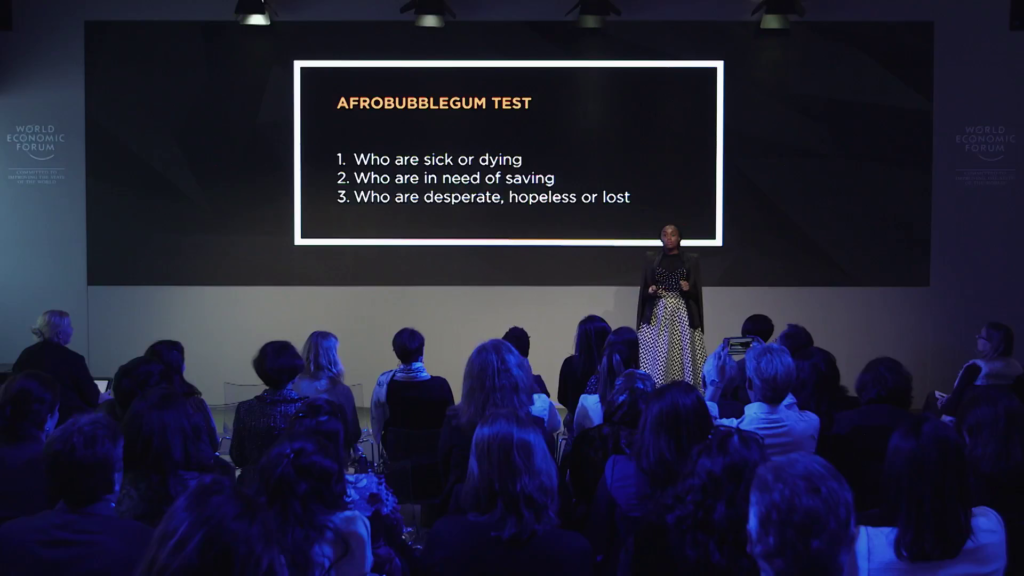

But not everybody can create Afrobubblegum art. It has to answer a couple of questions. So for the Afrobubblegum test that we created, we have a series of three questions. And in order to pass the test you have to answer “no” to the following three questions. The first question, Are there any Africans who are sick or dying in this piece? Are there any Africans in need of saving? Are there any who are desperate, hopeless, or lost? And if you can answer no to all three of these questions then surely you’re an Afrobubblegum artist.

And what was great to discover is that there’s been a history of Afrobubblegum art through Africa. In the 60s and 70s we had these amazing lookbooks, or photo magazines, or photo comics. And we had Son of Samsom. We had Cobra, the serpentine shero. And we had The Spear. The Spear had a charming way with girls, and a deadly way with thugs.

And they were truly a pan-African collaboration. They were written in South Africa. They were shot in Swaziland. They were… No, actually they were written in Nigeria. They were shot in Swaziland. They were edited in South Africa. And they were printed in Kenya and Ghana, and distributed across Anglophone Africa. And hundreds of thousands of copies of each issue would go out across the continent. And this is in colonial Africa and in Apartheid Africa, and we had a chance to see ourselves as heroes. Which is great because if we can see ourselves as heroes then maybe we can imagine for ourselves a radical hope for a better future.

So. More presently, in Kenya we have the work of Osborne Macharia. And Osborne created in his series The League of Extravagant Grannies. And these are retired women who were industry and government leaders. And just looking at their work you can see how they challenge power dynamics and gender roles in Africa.

Then what he went on to do is that he found very ordinary everyday women and made them high fashion models. And these women, as a result of being in his work, they felt so privileged and they felt seen and acknowledged through joy. They were celebrated because of everything that they can be and everything they had not imagined that they could be. So he started to create joy cultures through his work.

But he’s not the only person who’s creating joy cultures. In Abidjan, we have Laetitia Ky. And she uses her hair to create art. And her art is a version of her Africa, which is whimsical, and light, and fun, and frivolous. And I often imagine if these are the kind of images that we used to communicate NGO messaging, or foreign policy communication, what would we think about Africa then? Would we think that we are worthy of the pursuit of happiness?

Then, going to Nigeria we have Dennis Osadebe. And he creates what he calls “Neo-African” art. And he creates a series of afronauts. This is the Nigeria that he knows and this is the nature we should be engaging with. It’s the nature of full of honor. It’s the Nigeria full of fun. It’s the major you full of wisdom, and light, and love.

These images are the reason that we want to engage with Africa. These are the reasons that we want to get to know each other. Because we can see a sense of joy about ourselves, and that comes together. I think that given that joy is an inhibitor of fear, then we will find more commonality in joy then we will in suffering.

And we’ll also imagine unimaginable worlds like the worlds of Nnedi Okorafor, where she creates women who have the ability to fly, or leave Earth to go to a university in space, or try and master their sorcery. The great, amazing images of Africa. And though she has many themes in her work, the work is not about the themes. She creates because she wants to watch girls fly. She wants to watch girls having fun.

And I do the same thing in my own creation. I’m a filmmaker. And I try and create because of the people who inspire me, the people who give me love and who encourage me, and the people who make me want to defend their image. Because I want to honor them. And I know the power of images so I create beautiful images of people for that sake. I do not want them to be misrepresented. And I know the power of creating a new stereotype.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3elKofS43xM

We are Afrobubblegum artists. We create for the joy of creating. We create not in reaction to the West but because we are artists—we imagine. We imagine our future, we imagine our past, and sometimes we mix them both together. And we are Afrobubblegum artists because we believe in a fun, fierce, and frivolous Africa. And in time, the next person who asks me why is my film so important, maybe I’ll say, “Actually it really isn’t that important, not in the way that you think. It’s important because it shows a different view. A much needed view of a global Africa.” And, the next time we hear this tale about the lions learning to speak we will fight back by saying the lions are speaking. And they’re speaking to each other. And maybe now it’s time for the hunter to learn their joy-filled language. Thank you so much.