I want to get back to something Jay said. “See the invisible, understand the infrastructure, do something about it.” That’s really what I’ve been doing for the last few years.

This is a book my mom gave me. It belonged to her family. It’s the 1942 edition. This is the Citizen’s Advice Notes. It was given by the government, and this was actually given by the National Council for Social Service. Inside this book is basically a Bible of how you can live at that point, because there was massive rationing. You couldn’t get—anything that you wanted to do, you couldn’t throw food away, you had to get all your furniture through certain places, etc., you had to grow your own crops.

This is a book my mom gave me. It belonged to her family. It’s the 1942 edition. This is the Citizen’s Advice Notes. It was given by the government, and this was actually given by the National Council for Social Service. Inside this book is basically a Bible of how you can live at that point, because there was massive rationing. You couldn’t get—anything that you wanted to do, you couldn’t throw food away, you had to get all your furniture through certain places, etc., you had to grow your own crops.

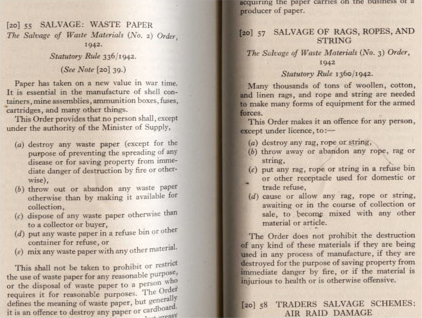

Flash forward to the pages on salvage. This is from the Ministry of Salvage specifically. Two areas, one on waste paper, one on string. There was no paper pulp being shipped in, so we talk about the infrastructure, it had to be completely rethought at this point. And they really need paper, because they used it for the ammunition boxes, etc. So you weren’t allowed to do certain things. You weren’t allowed to destroy any waste paper. You weren’t allowed to wrap any food up in waste paper. You weren’t allowed to use it for packaging. You weren’t allowed to throw it away with other mixed materials. You weren’t allowed to do posters that were bigger than about [holds hands to indicate ~11“x17”]. And you definitely weren’t allowed to use it for promoting things.

Flash forward to the pages on salvage. This is from the Ministry of Salvage specifically. Two areas, one on waste paper, one on string. There was no paper pulp being shipped in, so we talk about the infrastructure, it had to be completely rethought at this point. And they really need paper, because they used it for the ammunition boxes, etc. So you weren’t allowed to do certain things. You weren’t allowed to destroy any waste paper. You weren’t allowed to wrap any food up in waste paper. You weren’t allowed to use it for packaging. You weren’t allowed to throw it away with other mixed materials. You weren’t allowed to do posters that were bigger than about [holds hands to indicate ~11“x17”]. And you definitely weren’t allowed to use it for promoting things.

The same with string. You weren’t allowed to destroy any string that was about bigger than [indicates ~12″]. You weren’t allowed to mix it. You weren’t allowed to throw it away. You weren’t allowed to burn it. You had to keep it. You had to give it back to the right people.

So zip forward, this is two articles from the Sun in 2009 about people being buried in their own shopping and waste, this kind of rising obsession about stuff, how we identify ourselves. There’s always this thing about asking your kids, “What do you want to be when you grow up?” and your kids go, “Oh, I want to be an astronaut, I want to be a doctor.” And actually now they’re, “I want want to own a Gucci handbag and I want to drive a fast car.” So the way we’re identifying ourselves is through stuff that we aspire to rather than the people that we want to be.

So zip forward, this is two articles from the Sun in 2009 about people being buried in their own shopping and waste, this kind of rising obsession about stuff, how we identify ourselves. There’s always this thing about asking your kids, “What do you want to be when you grow up?” and your kids go, “Oh, I want to be an astronaut, I want to be a doctor.” And actually now they’re, “I want want to own a Gucci handbag and I want to drive a fast car.” So the way we’re identifying ourselves is through stuff that we aspire to rather than the people that we want to be.

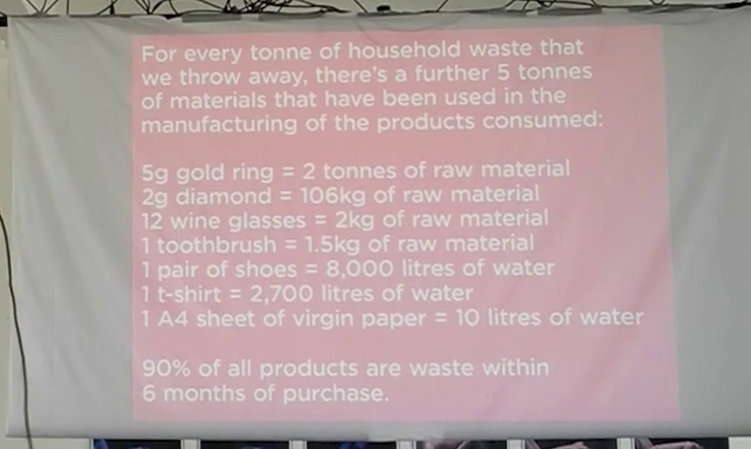

And the consequence of that, we talk about materials and we talk about one kilo of copper. There’s actually a lot of work being done around a kind of material footprint that we will need to continue the way we live. That’s been very interesting to me as a designer because I can just see, if you talk about trying to be self-sufficient in a sort of village context, don’t have your list up there with plastic items on it because you are never going to be able to do it. Because these infrastructures where we get our stuff are absolutely massive. So for every ton of household waste that gets thrown away, there’s about five tons of material behind that. The ratio of things that go into our products is so extraordinary. For instance I’m kind of obsessed about toothbrushes, and I’ll talk about that in a minute. But if you think about the material that’s gone into just a normal toothbrush, a plastic disposable toothbrush—four months of use if you follow directions from the dentist. There’s 1.5 kilos of raw materials in those toothbrushes, a very very heavy, heavy toothbrush. A sheet of virgin A4 paper (so not recycled) has 10 liters of water in it, just one piece of paper.

And the consequence of that, we talk about materials and we talk about one kilo of copper. There’s actually a lot of work being done around a kind of material footprint that we will need to continue the way we live. That’s been very interesting to me as a designer because I can just see, if you talk about trying to be self-sufficient in a sort of village context, don’t have your list up there with plastic items on it because you are never going to be able to do it. Because these infrastructures where we get our stuff are absolutely massive. So for every ton of household waste that gets thrown away, there’s about five tons of material behind that. The ratio of things that go into our products is so extraordinary. For instance I’m kind of obsessed about toothbrushes, and I’ll talk about that in a minute. But if you think about the material that’s gone into just a normal toothbrush, a plastic disposable toothbrush—four months of use if you follow directions from the dentist. There’s 1.5 kilos of raw materials in those toothbrushes, a very very heavy, heavy toothbrush. A sheet of virgin A4 paper (so not recycled) has 10 liters of water in it, just one piece of paper.

So all these hidden infrastructural and material costs go into the stuff that we just use very very quickly. We just kind of consume them, we don’t think about them, we just want to go on with our lives. When you start actually sort of picking away, looking at it all, you realize how shocking it is. And then once those products being made and all that material is going to waste just within the factory process, all the stuff we consume becomes waste. 90% of that becomes waste within six months. It’s very fast turnaround of things, and that’s durable stuff, it’s not [patchy?], it’s durable things. It’s quite shocking.

So this is something I think about when I brush my teeth. I have a particular toothbrush that I like. We all get attached to these things. So I just want to talk about toothbrushes, because we all have to use them, I hope. And we all have these strange relationships with toothbrushes, because it’s there usually around four months of use. If you use it for longer, you end up with a toothbrush like this. This product has been designed very very specifically for you. For instance, if you think about how you’re going to choose a toothbrush. You have a wall of toothbrushes there. They’ve designed it for color, they’ve designed it for price point, they’ve designed for medium and soft, it’s also been designed for ergonomics. So a huge amount of R&D has gone into that toothbrush; I would say very little about what happens to that toothbrush afterwards.

So this is something I think about when I brush my teeth. I have a particular toothbrush that I like. We all get attached to these things. So I just want to talk about toothbrushes, because we all have to use them, I hope. And we all have these strange relationships with toothbrushes, because it’s there usually around four months of use. If you use it for longer, you end up with a toothbrush like this. This product has been designed very very specifically for you. For instance, if you think about how you’re going to choose a toothbrush. You have a wall of toothbrushes there. They’ve designed it for color, they’ve designed it for price point, they’ve designed for medium and soft, it’s also been designed for ergonomics. So a huge amount of R&D has gone into that toothbrush; I would say very little about what happens to that toothbrush afterwards.

This is my toothbrush. It’s an Oral‑B one. And I did a bit of a quick material LCA, which is a life-cycle analysis, and worked out there were at least four types of plastic in that toothbrush. There’s the sponge bit, the hard bit, the nylon—there’s two types of nylon in there. [The bristles.] And this toothbrush has been made, designed, and manufactured, for very fast cost-efficient manufacturing processes.

This is my toothbrush. It’s an Oral‑B one. And I did a bit of a quick material LCA, which is a life-cycle analysis, and worked out there were at least four types of plastic in that toothbrush. There’s the sponge bit, the hard bit, the nylon—there’s two types of nylon in there. [The bristles.] And this toothbrush has been made, designed, and manufactured, for very fast cost-efficient manufacturing processes.

And then I was on the beach, and I actually found this one, I brought it with me as well. [unclear sentence] This toothbrush I found on the beach in Wales and it’s probably been in the sea for about two years and it’s actually still completely usable. Because part of the thing is that these materials that we’re using for our products are completely over-specced. Plastic will last for about a thousand years. This type of plastic is very very strong, very hard-wearing. And this is actually a toothbrush that a friend sent me which is from the garbage patch in Hawaii on Kamilo Beach and you can see there’s still bristles on it. This has been in the sea for a very very long time and is still usable, if anyone is desperate.

Why is this an issue? I’m sure you’ve heard stories about the garbage patch in—there’s seven actually. And they’re not really patches, let’s get that clear. They’re actually more like soups of plastic, because plastic doesn’t biodegrade, it photo-degenerates. So it gets smaller and smaller and smaller. So we have all these issues about what kind of impact does all this stuff that we’re throwing away, is it actually going to turn around and bite us in the end? And this is a sample taken from a patch which has got a 1 in 6 ratio of plankton to plastic. There’s six times more plastic than plankton. So you can imagine the potential impact on the food chain, etc.

This is a toothbrush that my father brought back, and it’s actually a disposable four-month lifespan toothbrush, but it’s electric. So, you get two in a pack. You can actually at the moment get two packs for the price of one. So you can get a whole year’s worth of supply for eight quid. It’s actually got the WEEE directive sign which is the wheely bin with the cross in it, which as I think you know means that you can’t put it in the landfill. It has to go into the recycling system. It also tells you that it’s got a Duracell battery in the back and that has a four-month lifespan so either the head goes first or the battery. If you try and take the bottom off to try and put a new battery back in, it breaks a seal and stops working properly. I tried.

So we started to take it apart. This is as far as we got. I had to get my really rudimentary toolkit out. Sawed it in half. The first thing I realized was actually the motor in it isn’t attached to the head, so basically what it does, it makes your hand vibrate. And then it pats like that, but it doesn’t actually move. So it’s effectively electric brushing by osmosis. Talk about copper. This is where all your copper is, it’s in little tiny motors like this. I packed it all up, sent it over to my friend who works in a materials lab, and it’s got about 26 elements in this toothbrush and it’s got a four-month lifespan. So it’s quite interesting to think about that.

Why is that an issue? This is what we’ve been looking at. This take-make-waste flow. This is very linear. So we have no infrastructure set up, to find all these 26 elements. And these are so so tiny if you start to try and find, for instance the neodymium inside this toothbrush which makes the motor work, it’s so so tiny. How are we supposed to have this huge infrastructure to take this stuff out and get it back? Because these kinds of elements are on a particular list which is about scarcity. There are 14 critical elements that have been identified from the periodic table from Europe.

Approximately 80% of environmental costs are predetermined at the design stage. So there’s maybe a designer going, “Oh shit. You know, actually the way I’m designing this toothbrush is the reason why it’s ending up in landfill sites.”

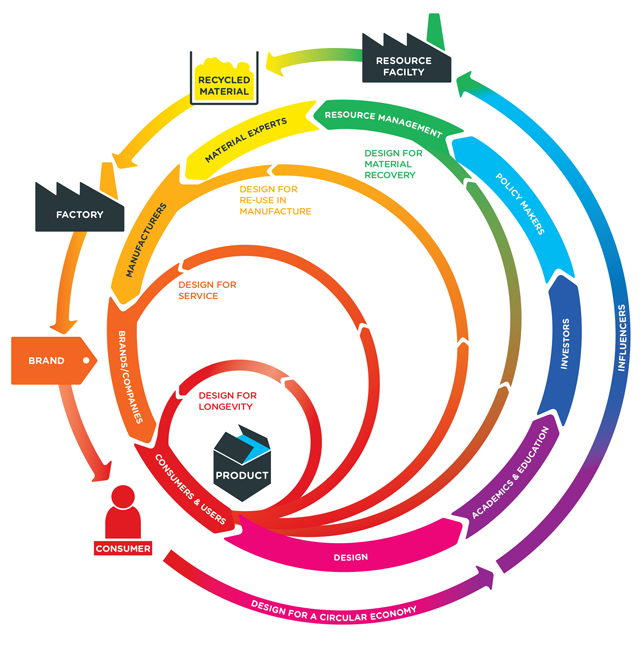

So this is the real premise of the project about recovery. It’s all about waste being a design flaw. Because what you want to do is design it in a way that people can get it back out again, and start building infrastructure that can do that. So the project in the RSA is really looking at how we can build infrastructure and co-creation systems with designers and mapping out all the players in that field. So you’ve got your landfill, your material recovery people—a huge amount of knowledge in this area, the chemists, the manufacturers, the brands, consumers, anthropologists, academics, investors, and policymakers, and try to work out who should be involved in this process.

So this is the real premise of the project about recovery. It’s all about waste being a design flaw. Because what you want to do is design it in a way that people can get it back out again, and start building infrastructure that can do that. So the project in the RSA is really looking at how we can build infrastructure and co-creation systems with designers and mapping out all the players in that field. So you’ve got your landfill, your material recovery people—a huge amount of knowledge in this area, the chemists, the manufacturers, the brands, consumers, anthropologists, academics, investors, and policymakers, and try to work out who should be involved in this process.

We’ve been taking up a slightly bigger toolkit now to eight different places around the country. Disused tin mines in Cornwall, lots of e‑recovery waste facilities, we’ve been in textiles, we’ve been doing paper, we’ve been looking at packaging and we’ve been looking at the infrastructure. How it’s collected, currently best practice. Which is usually crush-burn, crush-melt, see what you can get out.

We’ve been doing lots and lots of filming, it’s all on the website. And we’ve been taking things apart. This is the one of the first teardowns we did, which is a very established design tool, taking things apart to see what there is. It’s about finding the invisible, as Jay said. Taking a washing machine apart. We’ve taken laptops apart; very interesting. Particularly we’ve also been source mapping all of these materials, so following the design and manufacture route from tantalum and coltan mines in the Congo to your doorstep, and seeing how far it goes. It goes around the world about four times, for like 300 quid, which is a bargain, really.

Analyzing things to the greatest degree. This is a chemist and the inventor in residence at the science museum looking at the head of a toothbrush. We also found where all the metal is. There’s loads of metal pins in there, which we hadn’t found before. We’ve been getting designers to do ingredients lists of things to find out what they think are in it. We’ve also been taking things to the materials lab and really analyzing them and finding quite unexpected elements in there which we didn’t expect.

There’s forty elements in a mobile phone. I’d just like to say that again: there are forty elements in a mobile phone. Don’t worry about copper so much. Actually copper is on the critical elements list and the reason they’re on that list is because of scarcity, and the fact it’s harder to get out of the earth. There’s obviously a finite supply. It’s also about geopolitics, and we’ve been hearing a bit about that today as well. So these elements are getting harder and more expensive. Businesses are going, “Hold on a minute, I can’t do business as usual anymore because I can’t afford it.” And that’s why circular economy concepts are coming into play at the moment, and why designers are playing a more and more critical role in these things.

We’ve been taking periodic table cards with us, trying to get designers to work out what they think is in their products, and surprisingly they know very little. We’ve been taking packaging apart. This is quite an interesting one because we thought this was a very simple plastic piece that should be able to go through the infrastructure that we have for plastic recycling very easily and yet it has a massive metal spring in it which causes huge amounts of problems when you get it to the infrastructure stage where you’re trying to recover the materials because it contaminates loads. And talking to the people who make this (I had a conversation with them last week) they said, “Oh yeah, we used to have a plastic spring in there. But we found it was 2 cents more expensive so we took them all out and made them metal.” So when you talk to these people, they’re not talking about 2 cents, they’re talking about millions a day, producing this stuff. Millions a day. When you talk about creating new villages, creating new concepts around cities, you’ve got to think of this scale. It’s absolutely scary, because when these things go to that massive economics of scale, they become so important.

We found [?] lessons in things, and we found strange objects like toasters which actually have no value, and things which did have value like reused cadmium metal in engines. We basically took them apart, smashed them. And we’re now at a point where we’re redesigning them back up. We developed a model which takes thinking about the system design, thinking about longevity, thinking about material recovery and actually allowing people to start mapping out how they’d start designing things. So if you imagine that you’re designing a toothbrush, at the moment you kind of design it for longevity because the materials have got such a long lifespan when in fact we should be taking them out on a very fast recovery loop.

We found [?] lessons in things, and we found strange objects like toasters which actually have no value, and things which did have value like reused cadmium metal in engines. We basically took them apart, smashed them. And we’re now at a point where we’re redesigning them back up. We developed a model which takes thinking about the system design, thinking about longevity, thinking about material recovery and actually allowing people to start mapping out how they’d start designing things. So if you imagine that you’re designing a toothbrush, at the moment you kind of design it for longevity because the materials have got such a long lifespan when in fact we should be taking them out on a very fast recovery loop.