Hey, everyone. Thank you all for coming. I’m going to take you through a project that I started back home in Kenya that aims to collect vinyl that people just have chilling around at home.

So, basically we used to have the only pressing plant in East Africa between 1976 and 1990, and we used to press about a hundred and thirty thousand LPs every year. But right now there are lots of people who have those, but they’re not doing anything with them.

Before I go too far, I want to show you a clip that inspires me.

https://youtu.be/R4rMy1iA268?t=53

So, I swear I’m not going to Bay on you today. I m not about to do that. The why behind this project is, in December 2014, I was in Amsterdam. It was my first night there. I was supposed to be going for a festival, but during that night I said I’m going to go out. And I went to Trouw, which is where this image is from. And I watched nd_baumecker, who’s a really really great DJ playing a vinyl set. And in this room, it was all focused on him. And I loved the aesthetic of vinyl itself. I loved how it made us feel. At one point I remember crying, and it just took me away. And so I decided that, hey when I go back home I’m going to start collecting these things. And that’s how I started collecting. So, I’m not that old in collections. I don’t have a thousand records. But I am very much interested in the medium.

From there I basically decided that since Nairobi used to be a place where there was so much activity in terms of collection of records between the 70s and the 80s, bands used to travel literally twenty-four hours from Tanzania to come and record music in Nairobi, have it pressed and then distributed. So, there was a lot of activity going on, and the city’s pretty historic for that. But today, you can’t find any of that. We had record labels like Polydor, Phonogram, and AIT, they all had offices. They all had recording studios in Nairobi. But today. you can’t find any of that history anywhere.

So, it’s like there’s a paradigm shift between the time when we were buzzing and now. Modernization has basically made it all irrelevant. And between 1976 and 1990, there was actually a record-pressing plant that was established in Nairobi. And we were the only ones with one, so people would travel even from further. So, now it was people coming from Congo, AKA Zaire, and coming to record music. Influences between Kenyan musicians and musicians from Uganda and Tanzania, people who may have never met before but now because they had this one place where they had to record music and had these labels bringing them together, they were interacting. But what’s happened to all that music? What happened to all those people who were buying those records from back then? Where is it now?

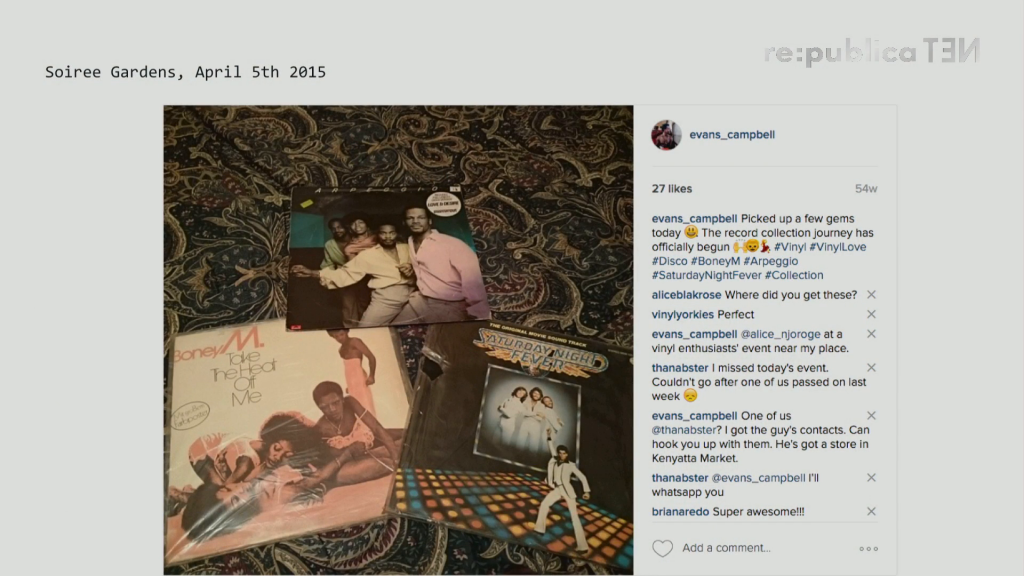

We have a meetup every month in Nairobi, every first Sunday of every month. It’s a place called Soiree Gardens, and this is where I bought my first records ever. So, it was just a few months after I got back home, and I went to this meetup and I bought these three records. They reflect what was the trend back in the day.

So, during the 70s, 80s, and early 90s, there were only two radio stations in the country. One, which aired in English, mainly played Afro-American music, as they called it. So think of all these kind of guys: T‑Connection, Kool & the Gang, Shalimar, disco funk, soul, that kind of stuff. So, a lot of people who were collecting from that time collected these.

But the kind of stuff I’m looking for is around the indigenous music which was recorded. Indigenous being it’s people who came all the way from Zaire, people who came from Tanzania, people who were recording even from Kenya themselves, Kenyan artists. They were speaking in vernacular languages, so they’d record Kikuyu, in Meru, in Swahili, which is the national language. Or, people who were coming from Zaire who were influenced by musicians from Kenya. So, there’s a popular music style called Benga, and its originated from the Western part of Kenya. But it became something that influenced genres like Lingala. So, how do we find that kind of music, because people were still buying that?

So, a lot of people who have records nowadays have them either as personal collections, so it’s something that existed in the family. You’ve had it all all your life. The other place that people get records is collectors who ship them in. So, basically I’ve come from Germany and I’m bringing everything I ever owned and I’m bringing it with me to Nairobi or to Kenya in general. And lastly, Europe, America, Japan. So like, I personally buy modern-day records, people who are still releasing vinyl now…I buy them, but I buy them from here, from Berlin. And then whenever I’m here or if someone’s here, I have them bring it to me. And as you can see that’s a whole process.

So in Kenya right now, the resurgence of vinyl that the rest of the world is feeling isn’t really a thing. It’s like someone who has just recently bought a player and they feel like they want to find records, they’re going to have a hard time finding new stuff. There are only two record stores in Nairobi, and both of them are pre-1990. The Melodica Record Store was established in 1971, so it’s a family business. It’s been around for ages. And then the other store is actually a store in… It’s very interesting how juxtaposed it is. So this store is here, and just next to it there are people who are roasting meat. And this place is known for roast meat. So, people walk in—it’s a market, it’s a massive market. People walk in, they’re having meat. And then just by somewhere, there’s this store, owned by a guy called James AKA Jimmy. And Jimmy is actually one of the people who sell records at the monthly meetups. So that’s the only way you can get records in Nairobi right now, aside from actually looking for them yourself, like I am, and going to people and finding them.

So, the aim of the project is to save the vinyl. There are so many people who have lots of it, and they’re not doing anything with it. Basically, I’ve got tons of it… Like, I remember everyone I met and told that, “Hey, I collect vinyl on the side. It’s a project I do.” They tell me, “Oh, my granddad has some. They’re just…I don’t know where they are.” Or, “My dad used to collect those.” Or, “We used to play Frisbee with that,” you know. Or, “We spoilt the player, and now no one plays them.”

So that’s the experience I’ve been having a lot of the time. And it made me question why people would let that music die. Because in reality, now we’ve got Beyoncé, we’ve got Rihanna, we’ve got Jay Z. But we used to have people like Papa Wemba, who were making amazing music. And they used to record some of it in Nairobi. But where is it? We have it, but you can’t find some of that stuff on Spotify. You can’t find it on YouTube. It’s golden music. The new generation of musicians coming up in Kenya needs to find some of that for inspiration and use it as base material. And they’re actually looking for it, but they can’t find it.

For example, there’s a project in Kenya and across East Africa, actually, called the Santuri Project, and basically they bring together artists and they put them together through a boot camp of about a week. And they record music. So, they bring expert sound engineers. They have a partnership with Ableton. There is equipment there. They record sounds, they record drum kits, they record all sorts of production material, and then they share it. So, with collectives like that in existence, the kind of project I’m putting together with this is to try and share some of that original material that can’t be found now with people like those, so that more music and be created using classic, original inspiration.

So, the process behind it is I basically…it’s very personal. so I have to identify people who have records and who are willing to actually donate them for this cause. The process of that, I have learned very fast, is difficult. Lots of people will tell you, “Hey, we have these things at home, and they’re just chilling. Maybe you can come get them.” But following up with those people and getting them to actually give them to you is the next biggest part.

After I get them, I organize for the collection. So, I come out to wherever you are in the country. Most people have them in the rural areas, so I have to plan a trip to go get them, maybe two hundred kilometers out of Nairobi, three hundred, four hundred. Then from there, I catalog the releases. So, some some of the productions that we had made in Kenya had catalog numbers that are recognizable on Bandcamp. So it’s something that was made for Germany and then brought to Kenya. Because Polydor, Phonogram, all those record labels were in Kenya.

But some aren’t even there. They had their catalog numbers based on the fact that they were produced in Kenya. So, how do you get that on Discogs? How do you get Discogs recognizing that music was made beyond Germany, America, and Japan?

Then restoration. This process is particularly difficult because, limited resources. But essentially, most of records I get have soup stains from the 1970s. And you know, the kids did something and they nicked one part of it. So it’s pretty difficult to actually play that stuff.

And then digitization. This is an end goal that I have. I honestly haven’t actually started digitizing some of the music I’ve found because most of it is actually available already. So I’m still looking to get that vernacular music, that original Kenyan music, original Tanzanian music.

My challenges so far, it’s mainly been limited resources. One, a lot of the people that I’ve met have been interested in selling the records. So, on top of that you have this sudden interest in selling, and you’re wondering, “If I don’t buy these records from you, you’re not going to do anything with them. You’re going to basically just leave them. But if I do, you don’t understand the painstaking process of restoring them. And also, you don’t really value them as much as you’re currently valuing them. It’s just something that you’re interested in now because you think they’re valuable.” Of course they are valuable, but you can understand the sudden read.

The non-Internet targets is in essence, there are lots of people who have these things, but using the Internet to get to them is not the best way. So, it’s my grandmother who has these records. If I read your post on Facebook, it’s part of a post from 9gag, and there’s a post from Brolife[?] and then it gets lost in all the noise. So using the Internet doesn’t really work. It has to be completely personal. It kind of has to be door to door.

The limited resources, aside from the restoration bit, it’s also the digitization bit. You need to have turntables. You need to have a sound card. You need to have a bunch of things that allow you to actually collect these records and make them digital.

Finally, before I move into the Q&A, I would like to credit David Tinning. David Tinning started the Santuri project, and he wrote a seminal piece about records in East Africa. He was living in Tanzania for a while. He went to a certain record store, and he was following the history of how people were making records back in the day. In Tanzania as well, there’s been this huge death of the vinyl industry. So, people who have record stores, they’re mainly getting foreign clients. It’s tourists who are walking through town. They see a store with records and then they walk in and start buying.

People like me are considered different and weird, because essentially guys are like, “Why are you collecting these things? This is like Spotify. You can download an app for that. There’s like, so many alternatives now.”

But the idea is that this music shouldn’t be lost, and that’s what the Santuri project is also trying to do. Media Policy and Music Activity, it’s a piece of research that was done around the media situation in Kenya between 1970 and 1990. It talks about how the cassette rolled in, the factories had to be closed. Also the fact that there was only one record pressing plant in East Africa. Didn’t really help because it was a monopoly.

And some people couldn’t afford to make the music, but they were making great music. There’s even a story of a band that basically faked a different persona to record twice. So, they went in as Band A, and then later they sent a letter to the record studio and they said they were Band B. They went, recorded another album, and then it sold like crazy. And then later, the record label realized, “Oh, shit. It’s the same guys.”

And then inspirations. Joseph Mathai is a very close colleague, and he basically told me about Michael Bay and told me that if the nerves overwhelm me, I should not walk off the stage. And of course, Google.

With that I’d like to open up to a Q&A session. The main point of this presentation today was to just show you what I’m trying to do, but also I’m looking at if there are any collectors in the room, what is your experience with collection? Have you tried something in terms of going for legacy records? Or are you just curious about what it is like owning records in Kenya and looking for them, or being a collector?

Audience 1: I just was wondering about how your relationship, or if you have a relationship, with any DJs here. Because they’re finding the material here, or I don’t know where they’re finding it, either, and it’s become popular again, I think, to do sets only with African music all over. Or like, Awesome Tapes From Africa that’s bringing bringing tapes back. So, it’s people out there doing it, but maybe it’s not happening in Africa. It seems like you’re trying to incite that.

Evans Campbell: Yeah, so that’s the thing. There’s a lot of foreign interest in the music from the continent. But there’s no local interest in this. So that’s why you’ll find projects like Awesome Tapes From Africa, which is doing really really great work. Even the Santuri project wasn’t started by locals, as well.

I think, essentially, it’s important for people like me to step up and do something about it. Because at the end of the day, this music is going to end up being lost, and no one’s actually going to act and stuff. I don’t currently have any connections with DJs here in terms of like, “Hey, you’re looking for African stuff. Let me give it to you.” But I’m working towards eventually doing that.

So, the idea of this is not just keep it within Kenya or within projects in East Africa, but also to share it with the world, because essentially, more people need to learn that music and it’s going to inspire.

Audience 1: Do you have a web site, or something that you load— If your future idea to digitize them, would you make a library or…

Campbell: So, I’m probably going to… The way I’m probably going to work is not necessarily… Because digitizing it and then sharing via web sites is going to open up a whole other issue around copyright and stuff. But, essentially I intend to work with projects that are doing that kind of reclamation of music. So, like Santuri and any other projects that are around here that are doing that.

Any other questions, anyone?

Audience 1: What is the best album that you’ve found, dusting about in some basement? What’s the recommendation?

Campbell: By virtue of the fact that I never knew their name, I have to say finding Shalimar and Wham. Yeah. I was like… This is them? Wow. This is someone who’s like, not doing anything with this record, and I get to keep it and actually do something with it. Yeah. But I feel like the moment I’m going to have real joy is when I actually find local stuff. Which so far has not been that easy, actually.

Any other questions? Okay. If no one else has any other questions, I’d like to say thank you very much for listening. I’m around over the next two days. I’m in Berlin until the twenty-fourth. Talk to me. Let’s catch up. Let’s make this happen. Cool. Thank you.