Hi. I’m Maral. Thank you Golan for the intro.

These are keywords or tags that have been used in the studio over the past few days. And for my talk, I have to add one more tag so it’ll be easier for you to understand where I come from and where I stand. It is online privacy, censorship, security, in the Middle East, and more specifically in Iran. These are the tags that resonate with me the most, and this is because they are the closest to me because the projects that I’ve worked on are very much related to these tags.

So why Iran? First of all, I am Iranian. My parents are from Iran. I was born in Germany, though. So I have some sort of a cultural connection to that country. And to answer that question properly I have to go a little bit further into the past and tell you a little story.

We have to go back all the way to 2009. I don’t know if some of you may remember this or not. This is the year where Iran had its presidential elections that quickly turned into this massive civil movement. And this movement happened because against all expectations the president at the time, Ahmadinejad, who was a hardliner, defeated his opponent from the opposition, Mousavi. And the people didn’t like that. The result of that was that millions of people gathered in the streets of Iran. And you can see the color green here. This is a symbolic color for this movement, so this movement was called the Green Movement, or the Green Wave.

This is what happened offline in Iran.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bbdEf0QRsLM

And this is what happened offline in Iran as well, but it also happened online. And not only in Iran. This is Neda, one of the countless civilians who got shot and killed during the protest in Iran. Her death was one of the most “iconic” ones, and most viral ones if you wanted to say that too. And it’s interesting to see that YouTube never took down this video from the platform. Also, this year this death was captured from two different perspectives. So we have two videos of this death being recorded. And it’s always kind of hard for me to see these videos over and over again. So apologies for that, and also sorry if I made you sad with this. But I think it’s important to see. And also important for you to understand that this is what pissed me off. And this is also what made me do something, not about this, but made me start thinking about the following things.

The interesting thing about this is that Iranian protestors with mobile phones and cameras, they started to become citizen journalists. As soon as the protests in Iran became more violent, journalists were kicked out of the country. So we outside of Iran had to rely on citizen journalists who then reported about events like this over YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter. Not Twitter, not too much. But mostly YouTube.

This also annoyed the Iranian authorities. What they did was they restricted the Internet even more than they would do normally. These web sites like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube are normally censored in Iran. So uploading a video like this takes you a long time first of all, because the Internet connection speed in Iran is really really terribly slow. And then if it’s censored it means you need to have circumvention tools in order to get on these web sites. So [for] this sort of content to be online, I asked myself how the hell do they put this online this quickly? And how is it that the Iranian authorities still also get to arrest bloggers? And that is because during the protests, what they also did is the authorities never actually switched off the Internet entirely because they wanted to track down the people who upload these kinds of videos, which resulted in a lot of arrests of “online activists” and “offline activists” as well.

So I got curious, and I asked myself what is the Iranian Internet, and who is the Iranian user? I was pissed off enough, like I said, to take a step or to feel the urge to do something. To feel the urge of making something. And the thing that I really wanted to bring across was that censorship is happening in a different country, where it’s being used to bring across information, to make voices heard.

So what did I do? I applied for an MA at the University of Applied Sciences in Potsdam in Germany. I got accepted, and I started finding out more, without knowing what the end result should be. I’m a designer, so I’m not a actually a researcher, but I had to get in touch with a lot of other people who knew a lot more than me. So I spoke to journalists, activists, bloggers, you name it. And then started drawing the bigger picture in the way that I would understand it.

From The Iranian Internet, at Visualoop.

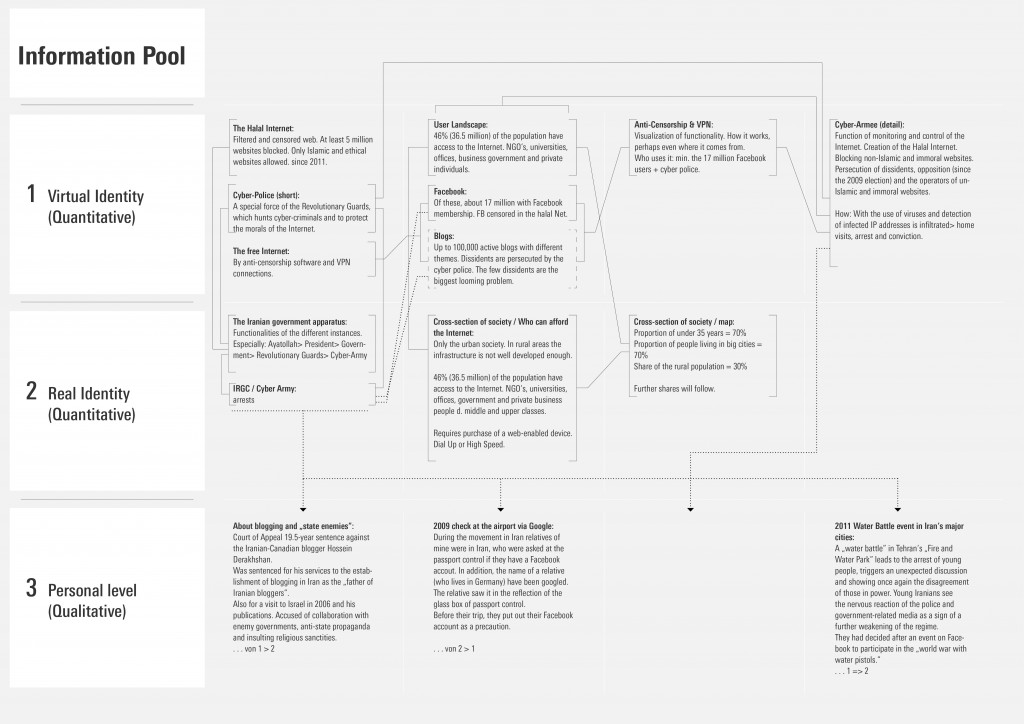

This is the information pool. This is how I like to refer to it. And what I did here is that I started clustering and relating the information that I got. And then I started simplifying what you see here, even though it’s quite easy to understand, but even more boiled down.

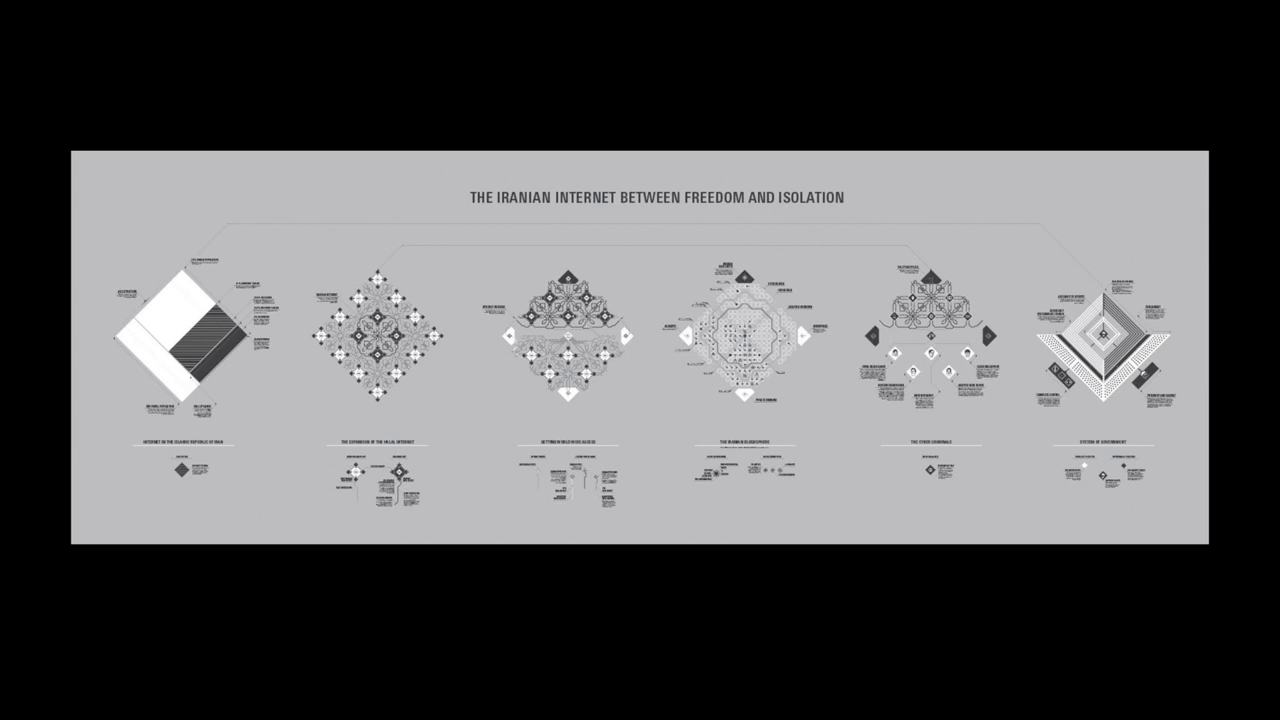

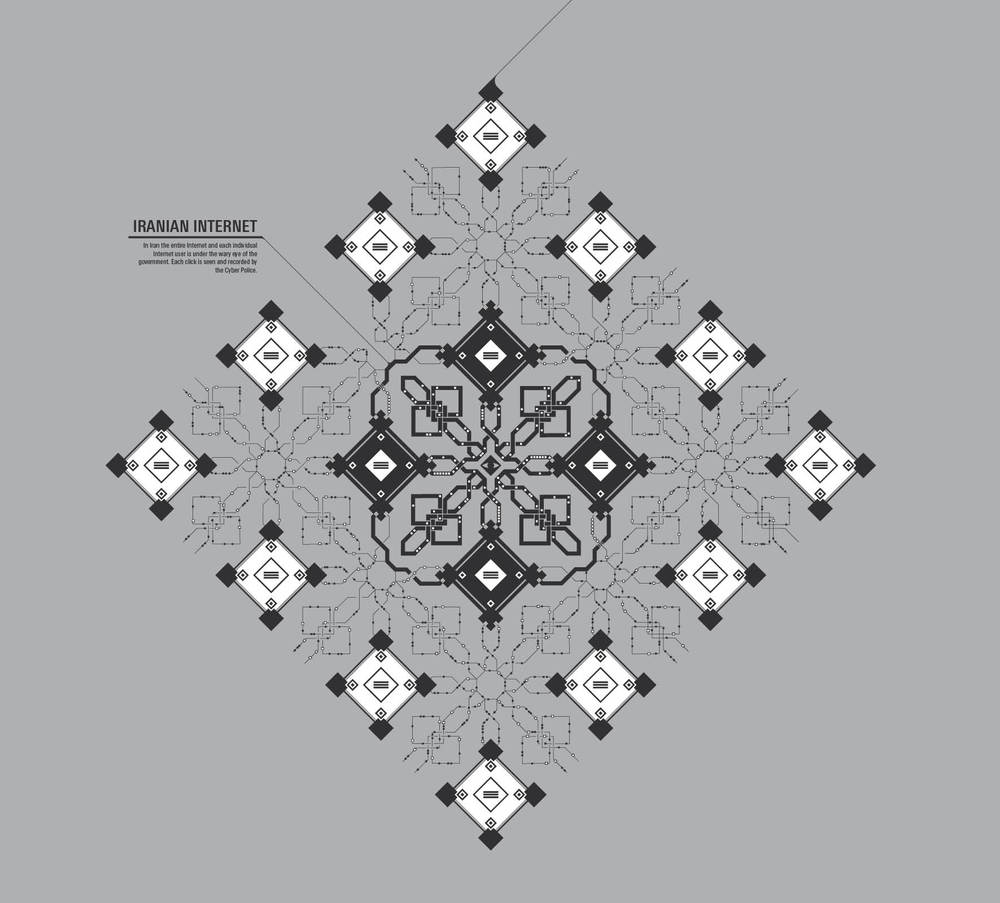

So I started structuring it further. There’s a step between this and that, but I want to show you other things as well. This is the end result, which answers the question for me about what the Iranian Internet is and who the Iranian user is. This visualization basically drills through the various fields of the Iranian Internet. And what I’m going to do now is to walk you through the different panels.

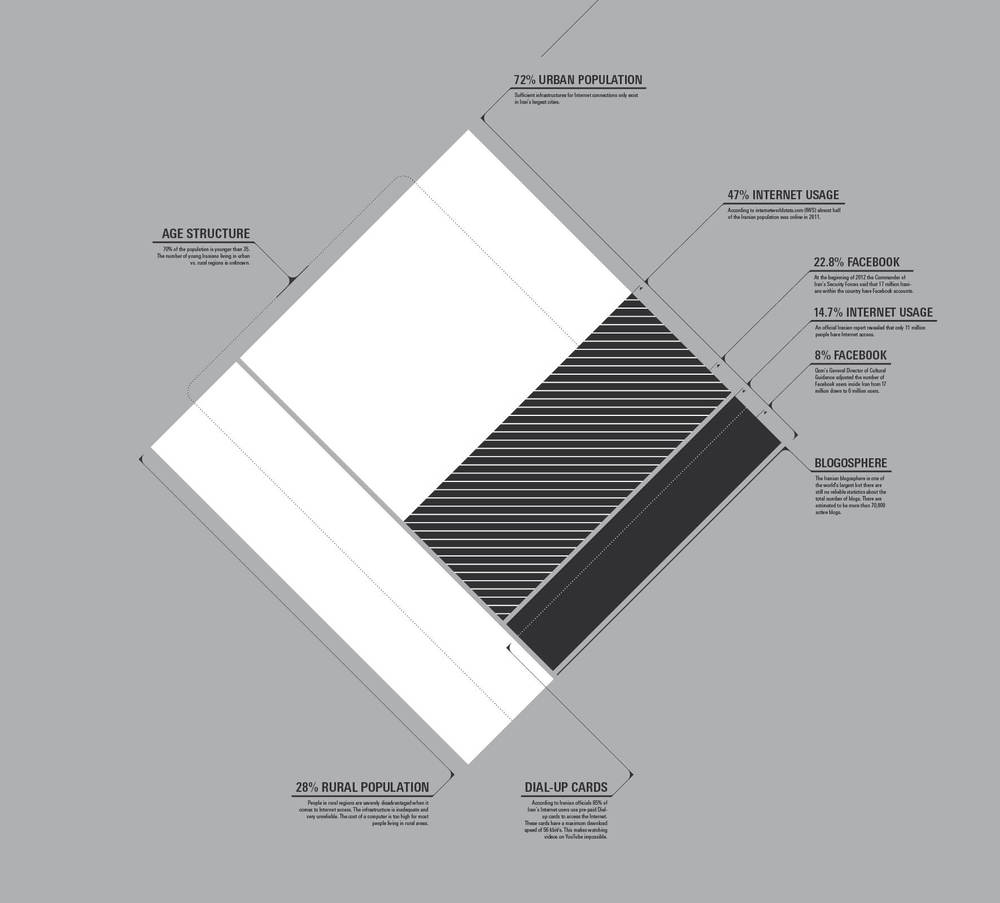

This is the first panel, and it’s based on numbers that I got. It’s basically telling you about the Internet penetration in Iran and where you are connected and where you’re not connected. So people who are in urban areas, they are the only ones who have access to the Internet, to the infrastructures of the Internet. And the number of Internet users is not a number you can rely on. You get different numbers from different institutions and the government itself, it tells you one thing a week from now and then two weeks later they tell you a different thing. So you can’t rely on the numbers you get there. Instead of finding only one number, I decided to visualize the problem and show the viewer of this project that there is intransparency happening; there is a conflict of numbers.

The second panel is basically looking at the black part of the previous panel, which is where the connection happens [when] you’re online. This illustrates what—the Internet is not a geographic place, but if it was, what would it look like in the Iranian context? So if you look at this, in the core of this visualization you have the so-called “halal Internet” which is a pure and censored Internet that Iran is trying to achieve. The thicker lines symbolize slow connections. And the dark, big squares are the Iranian ISPs and the white ones are the ISPs that are not in Iran.

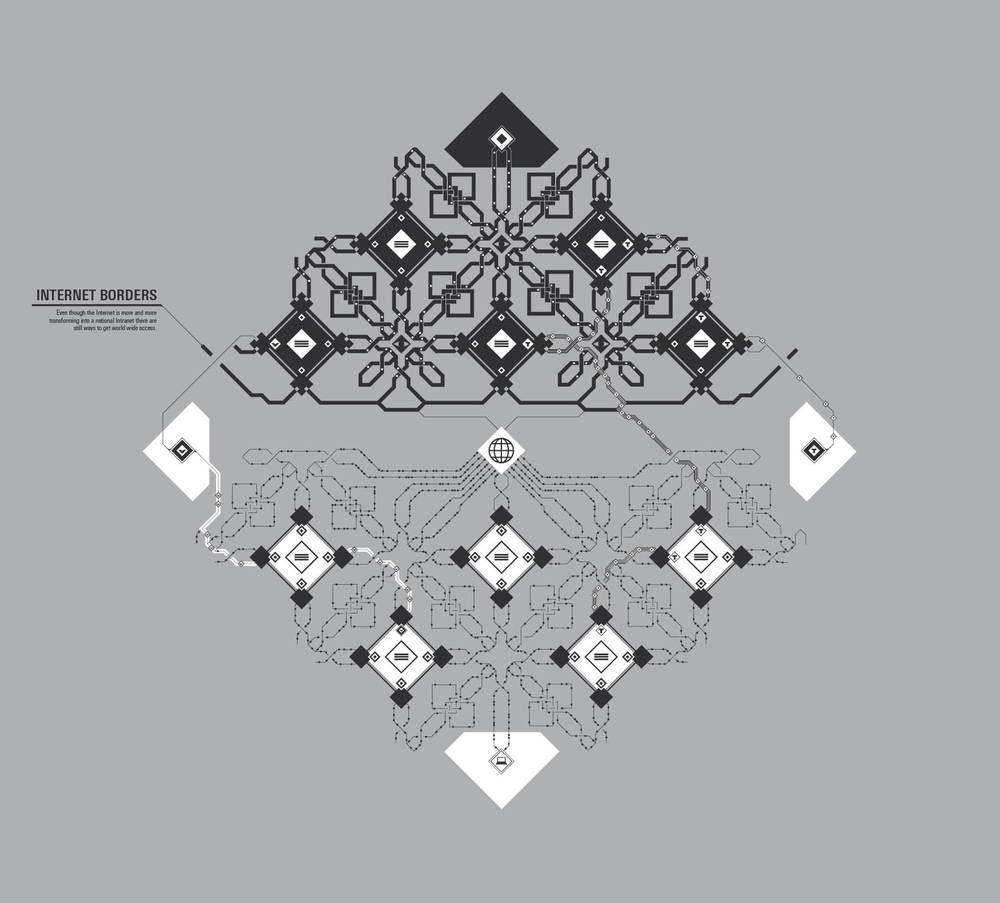

Then you go even further. You can see that there are gaps within these borders, and so this is what we look at in the next panel, where I try to describe the two most common circumvention tools that people use to get to blocked content. And those are VPN connections and using a Tor browser to get online. Once you have that, what can you do?

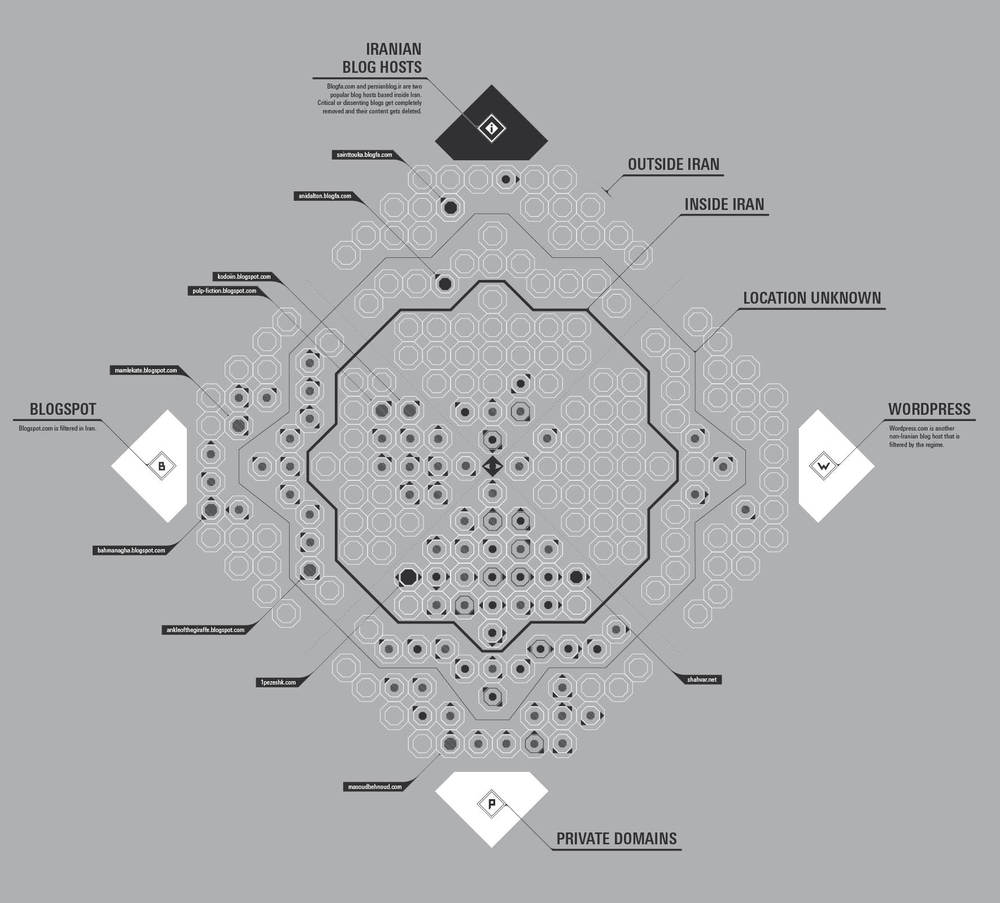

I was looking at a really small part of the blogosphere. Here are only four sections of it. So you have WordPress, Blogger, Iranian blog hosts, and private domains. The interesting thing about the Iranian blog hosts is that if you decide to put a blog online on an Iranian blog host, they have the authority of entirely deleting all your content from one day to the other if they are not happy with it. What they can’t do is to delete a blog on a non-Iranian blog host. So a lot of people decide to go on Blogger. One thing that is also interesting is that this is sliced into three different locations. The core is the people who are living inside Iran. The middle one is people who have an unknown location. And the outside one would be the people who live outside Iran.

What was interesting with the small sample of data that I had, I saw that a couple of people outside of Iran decided to have blogs on Iranian blog hosts. That can have several reasons. You either want to be able to have information available for people who are in the country for a specific time. Say you’re an activist from outside and you want to get information inside. The easiest way is to use an Iranian blog host. But that also means as soon as they see that you’re writing critical content, they take your blog out. This is the way that I would like to think about those outsiders, but they could also just be hardliners themselves or just curious about [testing?] other things.

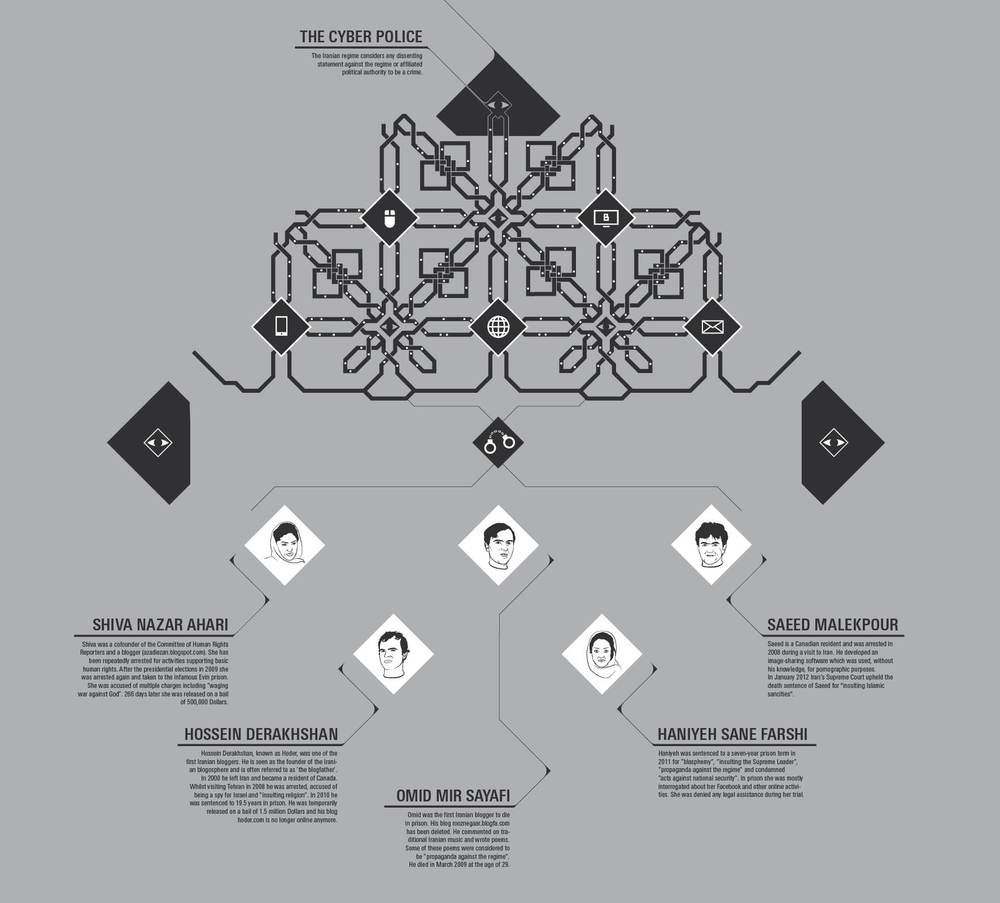

Then I asked myself who are the people who are the online activists? Who are the people who are writing these blogs, for example. This panel is looking at cyber-criminals as described by the authorities in Iran. You can see five stories here of people who have faced some trouble with the authorities. The guy in the middle [Omid Mir Sayafi], he was the first blogger who died in prison. What happens to bloggers and activists in Iran is that they just get treated like criminals who murder people, people who rape, like actual criminals, really really hardcore criminals. And they get tortured. So for example Omid, he was arrested twice. The content that he wrote on his blog was just satirical poems, and he was writing about music. That was all. So it’s super arbitrary. You can’t really predict whether you fall under a specific criteria of the regime that makes you a dissident. Sometimes you don’t even know that you are a dissident, which is also really painful.

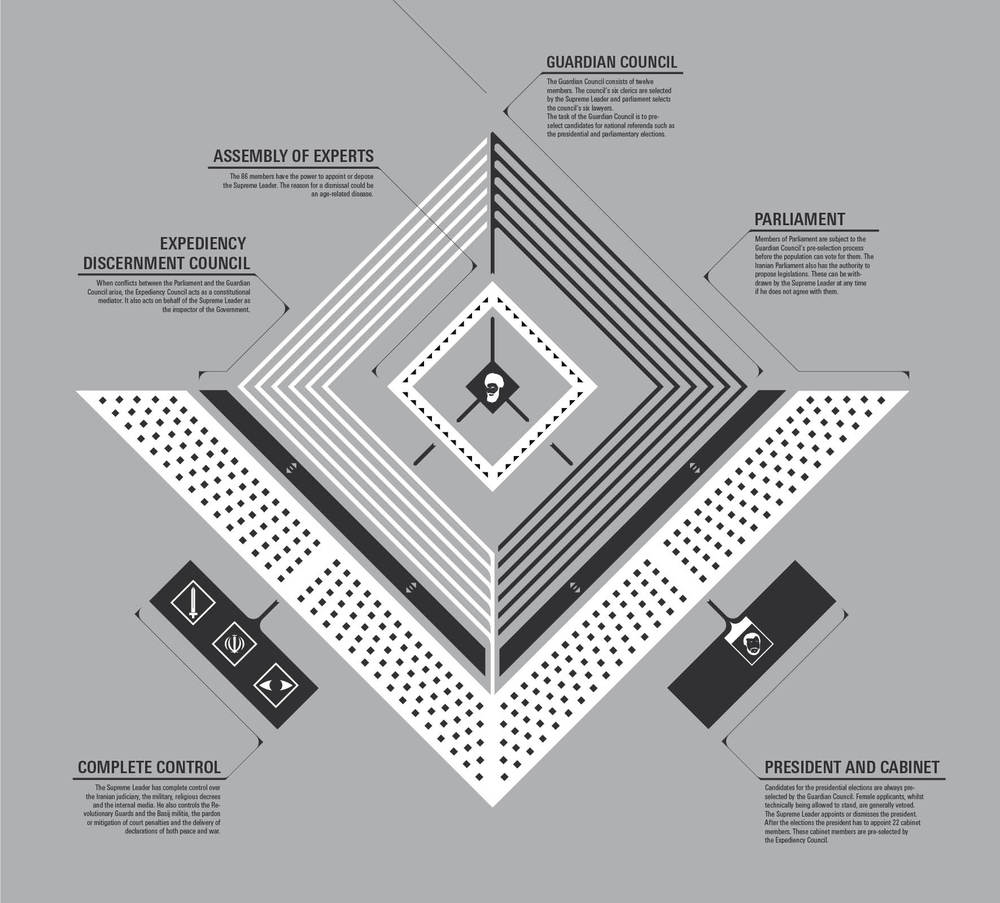

The last panel would be to show where the power comes from. What is the governmental structure that actually makes the decisions of arresting these people, or making laws, or conceptualizing the stupid halal internet, right? I won’t go into detail because this is not made for the screen. This is made for exhibition purposes. And I’m really grateful for this creating some noise. I just put it out and then really quickly it generated a lot of noise, which is awesome. Which was exactly what I wanted, because people started talking about this. And I think also it generated noise because it was a convenient point in time to speak about Iran first of all, and about visualizations as well.

One thing that happened after this, because this was an MA, it wasn’t made for the screen. There was never an online version of this. A friend of mine said we need to do something about this, we need to make this more accessible for people who aren’t in the space. He’s a filmmaker and he put this into motion, and I’m going to show this to you now.

https://vimeo.com/69750203

This is basically summing up everything that I said before in just three minutes. And it’s shareable online, which is great. And just a sidenote, it won an award just recently, finally. Thank you.