Timmons Roberts: The questions that come to my mind that I think we could sort of frame up this discussion is like, what would a winning coalition be to actually make a Green New Deal move forward in this country and more broadly? Who are the likely and the unlikely allies? What happens to the Green New Deal as the coalition expands? That is, Damian has brought together people who have really blown our minds about what a Green New Deal might look like, both aesthetically and then the people who’re actually making it happen. So, what happens to the idea of the Green New Deal? It’s clearly changing before our eyes.

Now, one of the big tensions related to that, to me that comes up again and again and again as I work locally in the state and the region, and more broadly even, is the issue of expedience, that is the urgent need for action, and the need for equity and inclusion. This tension is really quite brutal, I think, for organizing on this issue. We need to address a crisis that shoulda been solved thirty years ago, and which certainly has to be solved in the next ten years. So, how do we do this in a way that’s inclusive and more just, and I think Shalanda brought this up this morning.

Something that doesn’t get talked about enough is the opposition, and the barriers to a Green New Deal. Already right now, industries are organizing, as some students in my other group the Climate and Development Lab are studying, to kill the Green New Deal in the cradle.

There is a group called the Empowerment Alliance—I mean who could be against empowerment? But this is a group of the natural gas industry, funded entirely by the natural gas industry, to convince us that natural gas is the key to a better life and that we can’t really make the switch to renewables in a quick, ambitious way. And so they are mounting a public relations campaign right now with the best firms in the world, and they’re gonna roll it out state by state, And they’re gonna go after it. And it’s gonna look like it’s coming from local actors, local groups like labor unions or even communities. And they’re going to try to kill the Green New Deal. They’re going to be extremely difficult. We have to be ready and we have to be organized, and we have to have the arguments and coalitions that are effective.

Already we’re seeing ads from groups like the Competitive Enterprise Institute and others attacking the Green New Deal and making fun of the idea and really saying that it’s going to be horrible for our futures.

Finally we’ve had many issues come up, including from Myles Lennon this morning about the state, will it be an ally? Is it the way to justice and redemption or is it a trap that will bog down our movements and our effort at addressing the climate crisis and inequality crisis?

And then as Camilo, who we’re going to be hearing from as part of our panel in a moment mentioned you know. what is the role of academics? What’s our job here, and how do we do it? How are we part of this coalition?

So anyway I’m gonna stop. But we’re gonna have these four amazing speakers. We have Kian Goh, from Urban Planning at UCLA. We really appreciate her traveling all this way. Dan Traficonte from the DUSP, the Department of Urban Studies and Planning at MIT, and Ian Wells who’s an economic development professional in New York City. They’re both are JDs from the Harvard Law School. We have Alyssa Battistoni who’s at Harvard and a post-doc, who’s gonna talk about cyborg ecosocialism and gendered labor. We have Thea Riofrancos from Political Science here at Providence College.

Then we’re going to bring up afterwards Camilo Viveiros from the George Wiley Center. So you’ve seen that table out there? That’s his center that he’s director of. Really exciting poverty and inequality group here in Rhode Island that’s really on the forefront. Even the work that was mentioned by Jackie Patterson this morning about avoiding shutoffs and sort of energy justice is their campaign here.

Emma Bouton and Estrella Rodriguez are here from Sunrise. They’re really the lead organizers in Rhode Island among the few. And then Mara Dolan is way back there, we’re gonna bring her up too, who’s worked pulling together a Green New Deal from feminist groups from around the world in a group called WEDO, Women’s Environment and Development Organizations.

So it’s gonna be great. And we’re gonna finish this amazing day off with the most exciting panel of all. So Kian, do you wanna kick us off? Thanks.

Kian Goh: Holy shit. Holy shit.

Roberts: …the technology or—

Goh: No no, the whole day. So, this is an amazing day. My mind is indeed blown. My name is Kian Goh and I teach urban planning at UCLA. And I really want to thank Damian and Timmons and the teams here at RISD and Brown. It’s such a privilege to be here, and particularly on this panel. I’m looking forward to learning from folks I’ve really admired from afar for a while now.

Today’s the day of putting AOC on the screen as many times as possible.

So I’ll make some brief notes from a paper now in press titled Planning the Green New Deal: Climate Justice and the Politics of Sites and Scales. I have some notes to make sure I’m on track.

The urgency of climate change and the rise of a grassroots legislative political environmental movement in the United States should change the way urban planners think and act on spatial change and social justice. In the paper, I situate the contexts: the IPCC 1.5 degree and the Fourth National Climate Assessment reports, the organizing around the 2018 US elections, and I introduced the Green New Deal as a proposition that is environmental, state-driven, and woke.

The original New Deal reorganized society and space in the US. To what extent do we understand the potential of a Green New Deal to remake the nation’s cities and regions?

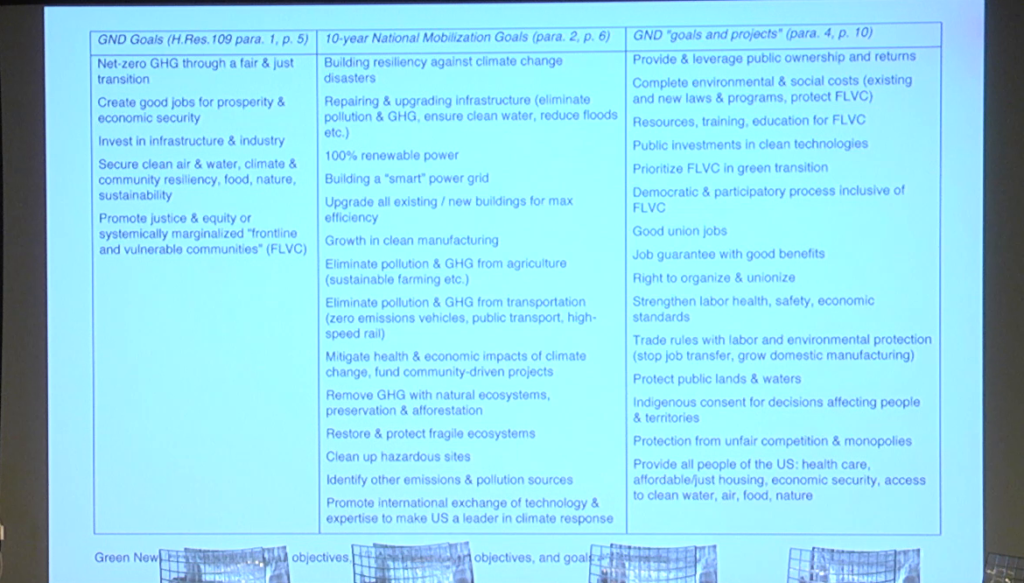

So I won’t go into detail in these following tables. Some of this has been covered before. So, the Green New Deal’s ten-year mobilization goals include resiliency, renewable energy, and national smart grid, and measures for energy efficiency and eliminating greenhouse gas emissions.

It is not really specific on projects, citing the need for transparent and inclusive consultation of stakeholders. It prioritizes the role of the federal government and public funding. And it emphasizes the unjust impacts of climate change on frontline and vulnerable communities.

The Green New Deal’s foregrounding of justice is important. It is necessarily bigger than a climate action plan.

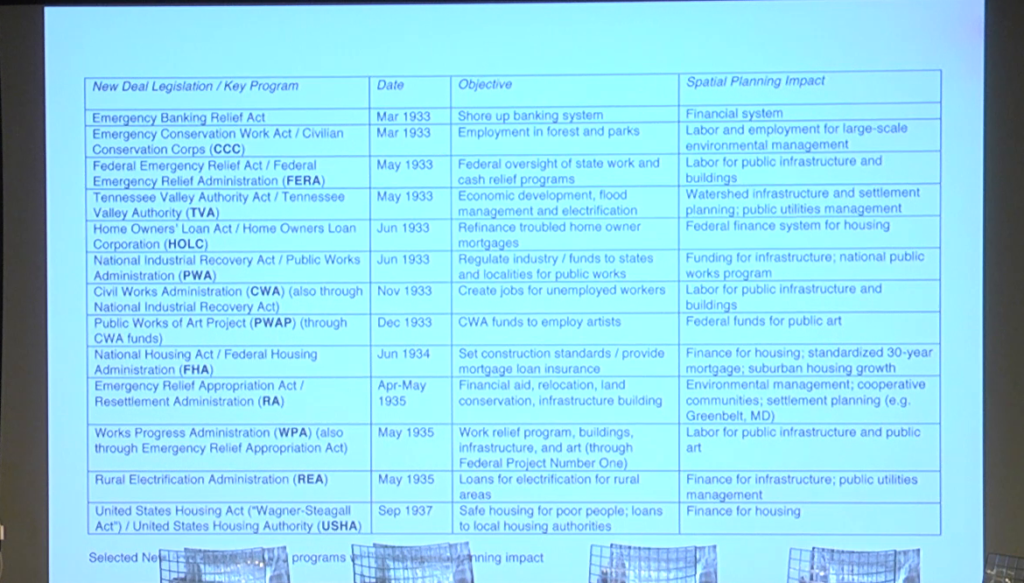

The original New Deal changed relationships between society and state. It constituted a crisis-fueled political movement and realignment of power, an ideological shift. So beginning with efforts to protect the banking system, it then expanded to work relief and to financing and building infrastructure and housing. And as a whole, it changed the way Americans saw the possibilities of work, housing, infrastructure, and art. It reinforced public and cooperative initiatives and reset the bounds of government interventions across space and time.

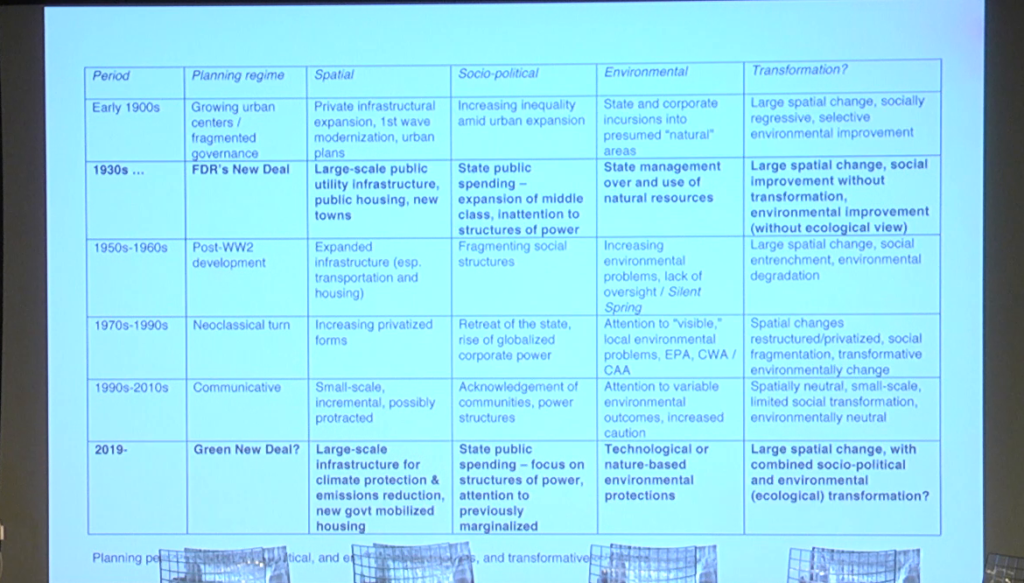

The Green New Deal presumes a parallel realignment of power and an ideological shift. It might be said to prefigure a new period of society and state relationships, with support for high levels of federal spending and coordination of industrial policy, spatial planning and development, and social programs. And associatedly a new planning regime, one inspired by but distinct from the original New Deal, and diverging from recent neoclassical and communicative turns in planning.

In the paper I speculate a little bit about the possible projects and plans of a Green New Deal. And I think many of these will be long-standing initiatives of planning, but under a Green New Deal might be classified into three core intertwined objectives. And they are greenhouse gas emission reductions, protections against and adaptation to climate impacts, and justice for marginalized populations.

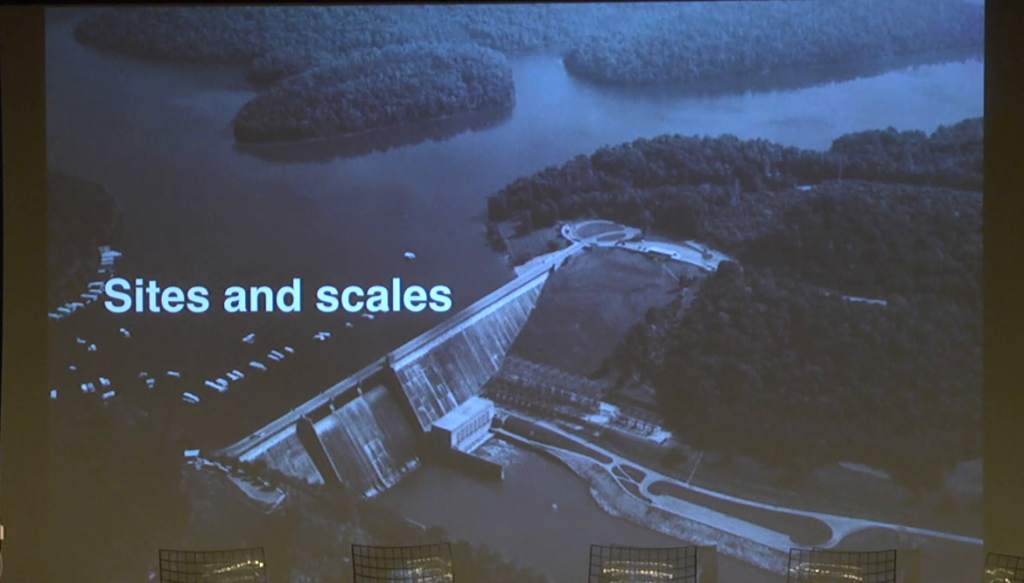

The 1930s New Deal changed the way planners perceived the sites and scales of planning. Green New Deal initiatives will take place in sites and scales that have not been part of previous planning efforts and will confound and complicate those that have.

New initiatives will have to consider longer time horizons and larger spatial extents than a typical ten-year plan, on the basis of uncertainty and incomplete information. For planners, this brings up contradictions between long-temporal and large-spatial scale reconfiguration and more immediate and small-scale social justice.

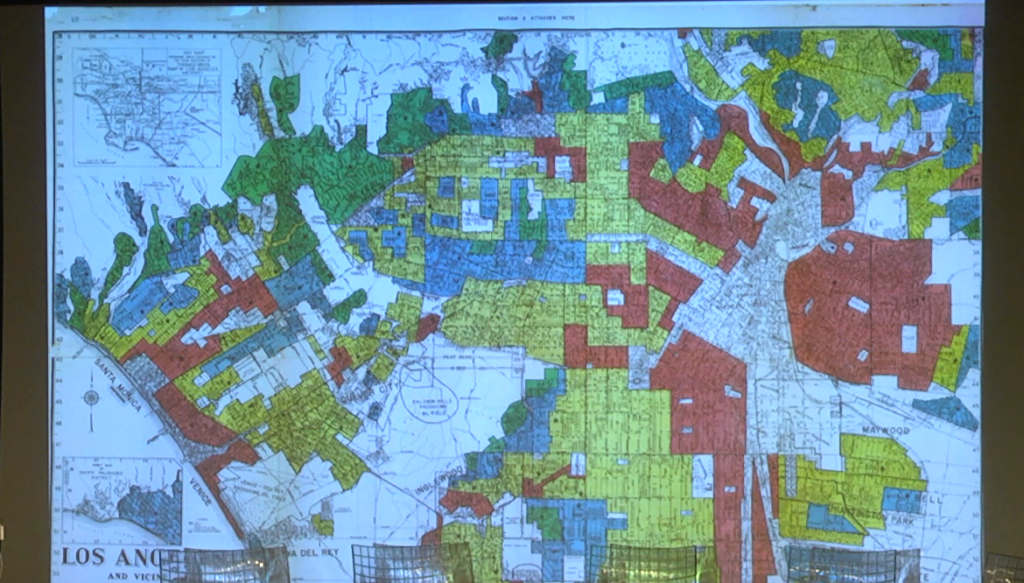

So take the examples of housing, transportation, and coastal infrastructure. In the first, planners have advocated for housing to be more energy-efficient, dense, and closer to jobs, amenities, and transportation. At the same time, many cities across the US are facing housing crisis and growing inequality. Grassroots activists in these cities have organized against development policies that lead to displacement of poor urban residents. They have fought against the state, the city, developers, and focus on the protection of local neighborhoods against large-scale change.

In the second example, planners recognized a need to decarbonize transportation systems by transitioning from cars and highways to rail. But progress on rail development in the US is slow at best. So in California, possibly the best state to try to undertake these kinds of programs, protests in regions outside of metropolitan centers and in urban peripheries have stymied the high-speed rail project. And so here, local opposition to large-scale change comes from a different part of the ideological spectrum, but invoking parallel claims in local community rights.

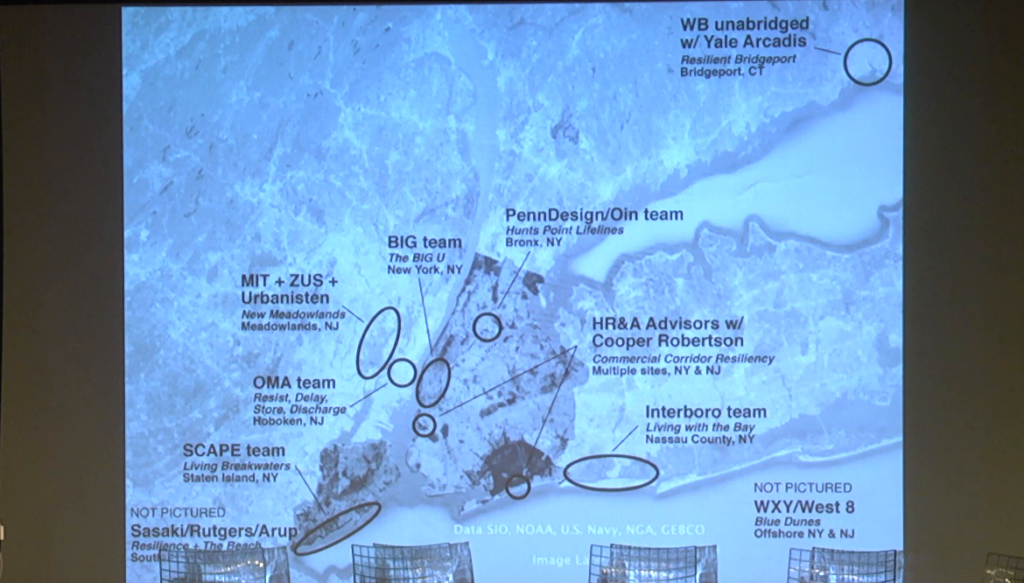

In the third example, planners and designers involved with Rebuild By Design in post-Hurricane Sandy New York envisioned regional multi-level protection. But proposals were constrained to localities by funding mechanisms and the competition directive to garner local stakeholder support. And this directive to garner that support was considered a more just corrective to previous planning eras, and as well appeasement for proposals that often seemed to be storm-resilient but market-compliant urban development.

In these examples, calls for local community-based justice are in conflict with the spatial environmental imperatives to address climate change.

Planners have learned critical lessons from community activists. Like the activists protesting housing displacement and infrastructure incursions, planning’s best practices—that are fairly recent—around issues like environment and equity have been to foreground the local scale and community interests, emphasizing community-scale approaches, community-based participatory planning, and community expertise and knowledge. This is a feature or a limitation depending how you choose to see it.

Concerns of justice, understood to be systemic and structural, are made concrete and actionable through reinforced accountability to communities. But when large-scale change is essential, how can efforts to protect local places and social relationships in the now lead to reconfigured societies and spaces in the future?

Further, the models we have, such as large-scale federal housing financing and infrastructural initiatives reminiscent of the New Deal, have not been necessarily just or conducive to community-based approaches—and folks have talked about this today. So planning’s practical charge for the Green New Deal is to think of the new bounds of practice for translating broad federal initiatives and very specific community-based concerns into actionable frameworks, given the objectives of emissions reductions, protections and adaptations, and justice.

These concerns of sites, scales, and politics are not new issues of urban governance and justice. So to close I’ll offer two interrelated concepts building on ideas from Iris Marion Young. So, Iris Marion Young, taking issue with communitarian notions of justice, offered ideas about difference without exclusion,

a broader notion of justice better aligned with the normative ideals of urban life. And empowerment without autonomy,

a more open and public participation achieved through regional-scale urban governance and democratized investment decisionmaking.

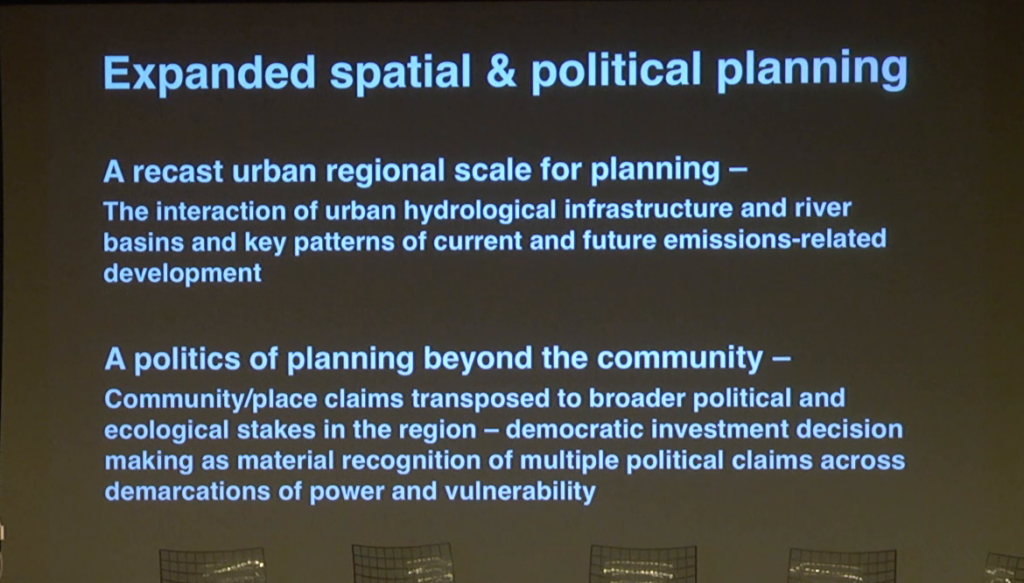

So first on the spatial scales of planning. A recast urban regional scale for climate planning would include the urban ecological watershed and key patterns of current and future and emissions-related development, including the spatial distribution of housing, transportation networks, and urban nature. So the prevalent planning question about where to build dense housing, for example, would not only involve proximity to the city center or to transportation hubs but considerations of the extent to which such development actually supports, together, low-carbon infrastructure, urban ecological linkages, and adaptation to climate impacts, and the rectification of patterns of socioeconomic marginalization.

Second, on the political relationships of planning. Community- and place-based activism center issues of historical injustice and raise legitimate claims for recognition and agency. But a new vision for just planning for climate change, beyond the community, would transpose such claims to the broader political and ecological stakes in the urban region. Because of the interconnectedness of the urban watershed and the factors of climate change, concerns of political justice at any one locality are interdependent with socioeconomic and environmental outcomes across the region. So here, Young’s ideas about public participation and investments are critical. Democratized investment decisionmaking would entail the material recognition of multiple political claims across urban regional demarcations of power and socioecological vulnerability.

So divisions about investments in protective and adaptive infrastructure, for example, or conversely disinvestments, or investments in climate retreat, are after all fights for recognition of communities across multiple sites.

For planners versed in community and participatory approaches that have been criticized for being depoliticized, this entails deeper political analysis of multiple histories of social and spacial oppressions and longer-term notions of justice. A bigger-than-local framework of justice turned towards climate change challenges would compel planners to think about justice as interconnected across political and ecological boundaries, working across often unaligned administrative areas and watersheds. It would ask planners to expand justice-oriented methods and actions beyond specific local community organizing, developing coalitions of constituents across localities towards broader environmental and social outcomes.

And I’ll end—one paragraph—by noting this: So the thoughts here are mainly in engagement with debates in urban studies and planning. And I think that actually betrays a little bit a somewhat limited notion of community. Ideas of community, ideally, are more relational and multipositional than some of the ways that I rehearsed it. And the most provocative and inspiring social movements right now, including the global climate justice movement, embrace expanded notions of community. And so I think that this is as much of an invitation for me, and possibly others, to rethink social movement building as it is to rethink planning. Thank you.

Further Reference

Climate Futures II event page