Thea Riofrancos: Ignore the screen behind me. I’ll get there.

Hi, I’m Thea Riofrancos, and my talk today which I think is entitled A Global Green New Deal though I don’t remember, something like that, also draws on A Planet to Win, which was already mentioned, and some of my current research on lithium and electric vehicle supply chains across the world.

So, the Green New Deal, usually thought of as a domestic policy. Thought of as a policy to radically, and quickly, aggressively decarbonize within the US, paired with a suite of social policies to lift up working-class and poor people in the US. But what I’d like to argue today is that we should think of the Green New Deal in global terms for several reasons.

In a world of globally-dispersed supply chains, an energy transition in the United States has implications for the extraction, production, and distribution of resources and technology in places well beyond US borders. So-called clean technologies such as lithium batteries and electric vehicles, wind turbines and solar panels, are made of minerals extracted from the Earth, manufactured in factories that still use dirty energy, and shipped through a carbon-intensive logistic network.

Each of these nodes are sites of environmental harm, violations of indigenous rights, and labor exploitation and repression. So in this context, it appears at first glance that there’s a stark tradeoff between the urgent goal of decarbonization in the United States or anywhere in the world, and our other social and environmental values. The inevitable imbrication of a domestic energy transition in a deeply unequal global economy thus raises the question, can a Green New Deal be globally just? I’ll argue, and we argue in our book, that it can be and also that it must be.

Climate justice is an internationalist planetary vision. The climate crisis doesn’t stop at US borders and neither should our vision for how to address it. Further, it’s vital that the low-carbon world that we need to build doesn’t reproduce the inequalities, dispossessions, and exploitations of fossil capitalism or the colonial capitalism on which fossil capitalism is built, where some lives are valued more than others and some pay the costs, social and environmental, for the wellbeing of others.

I also want to argue, though, that in addition to these reasons that are sort of founded in our political commitments to internationalism and global justice, that the supply chains that produce the technology that we need to build a low-carbon world are also particularly concrete and politically fruitful sites for policy intervention and grassroots mobilization.

So I think in general we’re used to thinking of the kind of international realm of climate politics. We kind of envision things like the Paris Agreements, right, so these relatively closed-door negotiations where mostly elite actors are figuring out how to like, not decarbonize, basically. Or not commit to anything binding. And that’s not in my view a very fruitful way to advance global climate justice. And I think kind of compared to those sites, the supply chains that build our renewable energy and clean technologies actually offer a lot of opportunities for promoting social justice.

So, what if instead of the kind of Paris Agreement vision we thought of these globally-dispersed and materially-grounded production of renewable energy as a terrain for both left public policy and also for new forms of transnational solidarity. Seen from this perspective, a whole new range of tools, mechanisms, and political strategies come into view.

The first of those is trade policy. For decades, trade policy has been completely coopted by the erroneously-called Free Trade Agreements, which enable perhaps the easy movement of goods, investment, capital, and finance, but by that same token encourage a race to the bottom for labor and environmental regulations, reinscribing the neocolonial world system.

What if instead our trade agreements promoted indigenous and worker rights and ecosystem integrity; accounted for the carbon emitted in production and distribution; and facilitated access to technology and economic redistribution between the Global North and Global South.

The growing trade in lithium, cobalt, electric vehicles, solar panels, and everything else that we need to build a low-carbon society provide an opening for a left vision of trade, defined against both neoliberalism and new forms of right-wing revanchist isolationism.

But we also know that better public policies and new forms of cooperation between governments, however well-intentioned, are never enough to remake the world order. We also need to change the way that we consume as well as build new grassroots alliances across borders.

So first, consumption. This is a very tricky question for the left, and I apologize that I missed the earlier panels but I assume it was something that was addressed. We’re all aware that consumption is highly unequal, as are of course contributions to emissions and environmental degradation. We know that the conspicuous overconsumption of the rich and the reckless practices of private firms are the main culprits of the climate crisis. But we also know that all of us need to consume differently to build a low-carbon world. Fewer cars and more mass transit, less meat and more vegetables, and overall shifting away from leisure defined as driving and shopping to low-carbon forms of public luxury.

It also turns out that our consumption choices, which are never individual but always the result of institutions, policies, and the balance of class power, matter tremendously for the supply chains I’ve been discussing. To take lithium batteries in particular, the more we can engage in collective consumption, riding electric buses together instead of driving individual Teslas, the less mined resources we use. Ditto for the more we can reuse and repair instead of discarding goods that are manufactured for obsolescence. Lithium batteries that are no longer powerful enough to charge a bus work just fine for battery storage on the renewable grid.

And last but not least I would like to underline the importance of solidarity across borders. Supply chains may be currently structured by the needs of capital, but they also always offer opportunities for workers and communities to exercise leverage. Scholars of supply chains and logistics networks call these chokepoints. The extraction of raw materials and the manufacturing and transportation of goods are also always potential sites of protest, disruption, and labor strikes.

And, as with any form of social mobilization, the denser the horizontal alliances are between workers and communities across these nodes, the more powerful they are, and the more likely they can stall or obstruct rapacious forms of extraction and force bosses to respect their rights.

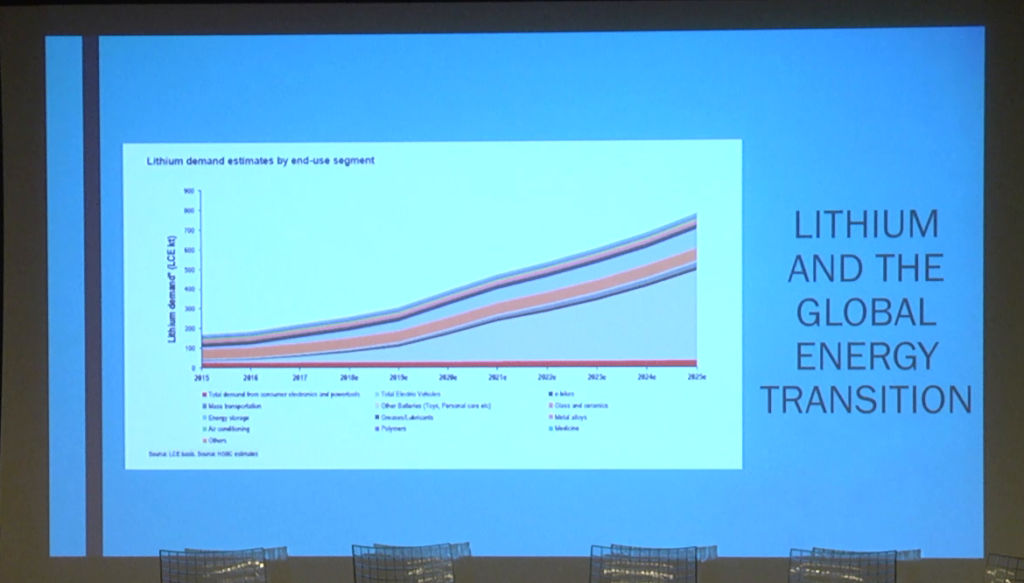

So here and kind of briefly I’m gonna pivot to a bit of my research on lithium extraction in Chile in particular as one kind of site of a broader project on the supply chains of electric vehicles. So for those that are not aware, this might be sort of redundant for folks in the room, but I just like to give a sense of the projected demand for lithium, which is a mined resource. It’s mined from brines, which I’ll talk about in a moment. It’s also mined from clay deposits and hard rock formations depending where in the world. And you can see that we’re on an upward trajectory.

Though it’s also kind of interesting—I don’t complicate things too much, but we haven’t actually entered this trajectory quite yet. It’s sort of like, each year it’s like next year we’re gonna see the sort of extreme increase in demand for lithium and for batteries and electric vehicles, and we haven’t quite gotten to that world yet. And that’s primarily because the policy environment hasn’t incentivized mass adoption of electric vehicles, something that our industrial policy folks can talk to us more about.

But anyway, regardless the idea’s we’ll need a lot more lithium and cobalt and nickel and all of the mined resources that go into lithium batteries and electric vehicles much moreso as time moves forward. And we could at any moment enter the sort of tipping point or have a dramatic uptake in electric vehicles.

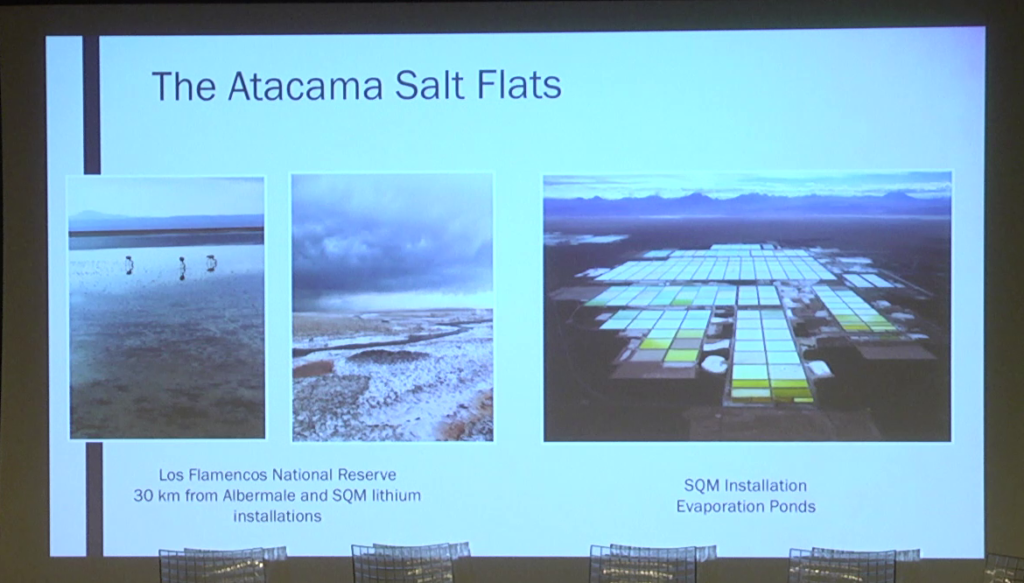

Chile is where I chose to do my initial fieldwork and it’s one of the top kind of three exporters of lithium on the global market right now. And it turns out that lithium extraction is very environmentally destructive in addition to posing harms to indigenous rights and livelihoods. So, one of the main issues with lithium extraction especially in brine deposits—and I’ll show you some images momentarily—is that it actually involves sucking water out of the Earth, right. It’s brine so it’s saltwater, it’s not water that we would drink but it is water that microorganisms live in and that other animals feed on, and in the process of extracting brine it also actually results in lowering the the freshwater table that humans and farmers and all of us need for drinking and agriculture.

So just to give you a sense of what things look like in the Atacama Desert in Chile, which is by the way the second-driest place on Earth after Antarctica, so water scarcity is a particularly kind of fraught issue. That’s what it looks like… [recording cuts short]

Further Reference

Climate Futures II event page