Hi, everybody. Thanks for coming out early this Saturday morning to hear from us. I’m going to stand up because I’m more comfortable standing up.

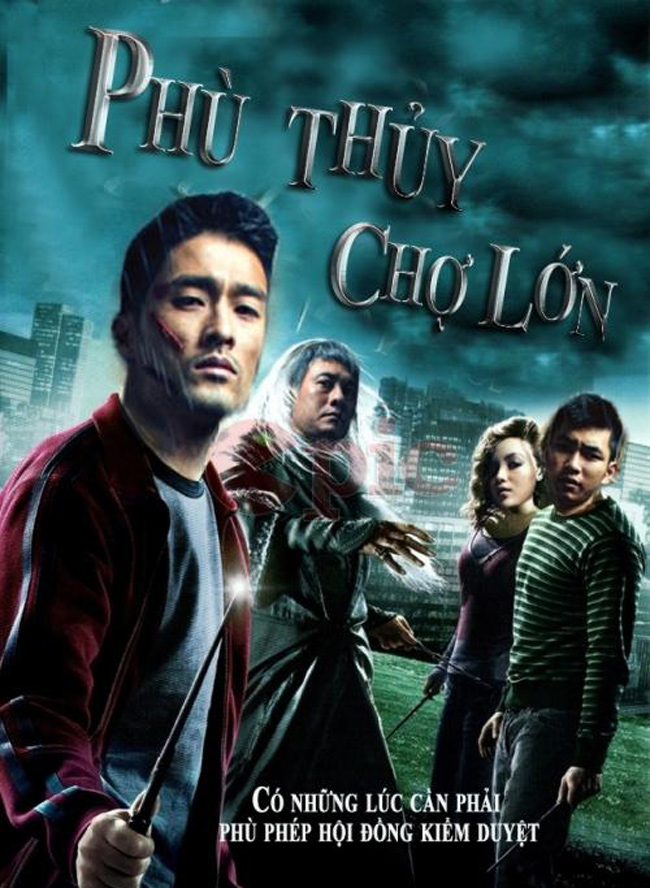

Last summer, people in Vietnam were eagerly anticipating the premier of a locally-produced film there called Bụi Đời Chợ Lớn, “The Street Children of Chinatown.” It was a formulaic gangster-style action film set in the Chinatown neighborhood of Ho Chi Minh City. People there were excited for it because it was set in Ho Chi Minh City, it was relatively rare for an import, and it was promoted heavily for weeks. But just a few days before the June opening date of the film, officials in the Ministry of Information and Communications cancelled the release of Bụi Đời Chợ Lớn. They said it was too violent and it didn’t reflect the social reality of Vietnam, so that weekend everybody went to see World War Z and White House Down instead. I did.

It’s not like this is without precedent. Vietnam has a long history of censoring popular entertainment. A year previously in 2012, the same government office had banned all in-country screenings of The Hunger Games on a similar premise, that it was too violent. What officials didn’t say at that time is that The Hunger Games depicts a popular revolution against a repressive, corrupt government of self-serving elites intent on keeping its people poor, ignorant, and powerless. It must’ve slipped their minds.

Image from Vietnam Officials Censor Homegrown Film, Prompting Populist Blowback at Vietmeme

But where people had taken the Hunger Games decision in stride the year before, something different happened last summer. This happened. Remixes and mashups of the film’s promotional poster began appearing online. Technically unsophisticated but clever parodies subtly mocking the Ministry’s decision. Of course they included the obligatory remix of Hitler reacting to the news.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UGGGJzv6ZME

Another version took a confrontation between two rival gangs that appeared in the film’s online trailer and tweaked it before censorship, and after censorship. A site that remixes panels and characters from the Japanese manga Doraemon took that idea, modified it, and posted their own version.

In a recursive iterative cycle, these images and hundreds other like them were created, modified, and shared thousands of times on Facebook, which has been blocked in Vietnam at the DNS level since 2009. They appeared in many online discussion forums that are so popular there, such as [Vietnamese names]. Where the Hunger Games decision came and went without much fanfare the year before, this time the issue didn’t go anywhere. It stayed alive, as every time someone shared one of these images, another conversation about it started. And not everybody believed that the film should have been shown. There were lots of online comments defending the ban, justifying the decision to kill Bụi Đời Chợ Lớn. That’s not surprising, but it is unusual because these very public debates and conversations about this topic, censorship, hadn’t really existed a year before. It’s also interesting because the people who created these images and shared them didn’t make their point with angry blog posts written in all-caps, but by using the tools of remix and pop culture and humor.

Vietnam of course is Asia’s other rapidly-developing autocratic Communist state. Like its neighbor to the North, [it] undertook quasi free market reforms a couple of decades ago and now Vietnam is in the midst of a huge economic boom. It has a big emerging middle class and an Internet penetration of nearly 40% among its 92 million people. Incidentally, Vietnam is the 13th largest nation in the world by population; true fact. As in China, almost all media in Vietnam is at least partly state-owned and very tightly controlled, and authorities there have a habit of jailing outspoken bloggers on charges of abusing democratic freedoms and spreading propaganda against the state. Last year sixty-one Vietnamese citizens were given lengthy prison terms for peacefully expressing themselves on the Internet, more than any nation in the world, except for one.

Unlike China, however, Vietnam’s Internet is relatively open. Google and YouTube are among the top-visited sites there. Most of the social media platforms that you and I use are available there. And despite the block on Facebook at the DNS level (easily circumvented) twenty million Vietnamese people update their status every day. That means that 70% of Vietnam’s Internet users have a Facebook page. In the US that figure’s 55%.

It’s also important to keep in mind that for generations Vietnam has nurtured a collectivist, Confucian ideology that places national development, political stability, social harmony, and respect for authority above almost all individual interests. A great firewall has never really been necessary here, between the chilling effect of regular arrests and imprisonments and decades of social conditioning, political commentary on the Internet is understandably rare. It’s considered dangerous, pointless, and—at least among older citizens—Un-Vietnamese. But that’s changing.

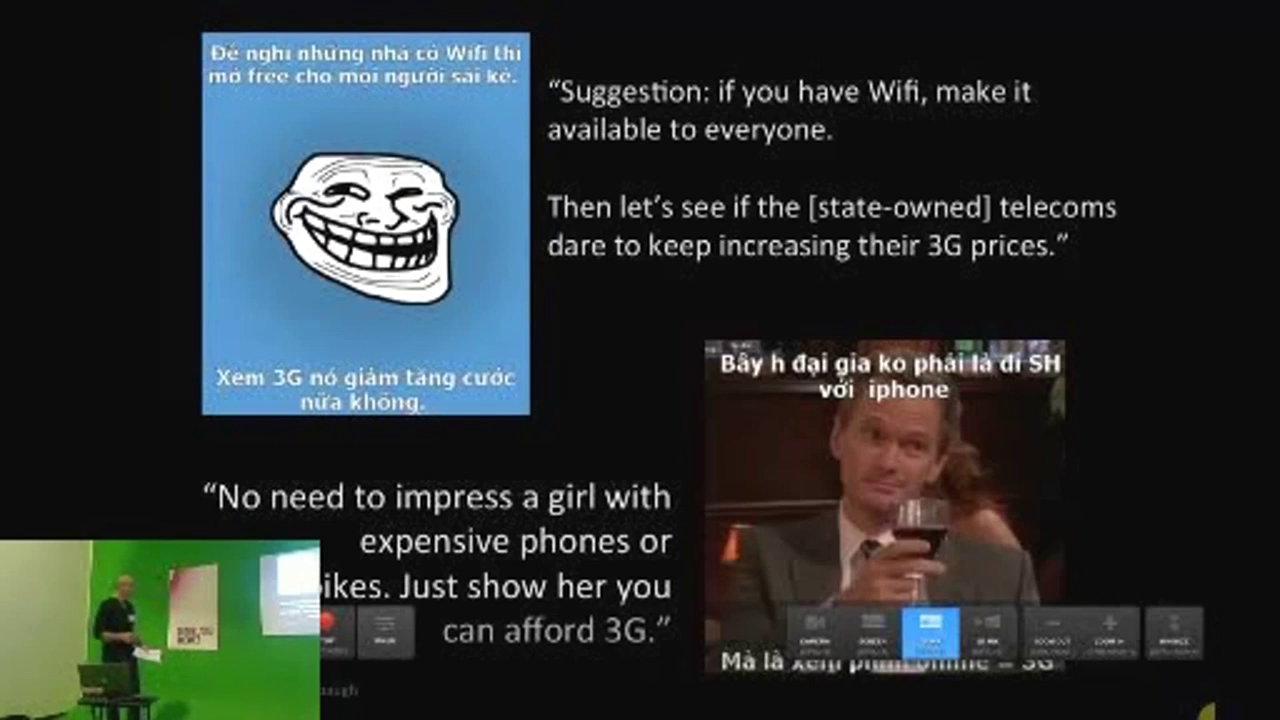

For the past five years I’ve taught a course called “Asian Cybercultures” at RMIT University. It’s an Australian off-shore campus in Saigon. Last spring I noticed that many of my students had begun citing examples of remix culture and user-generated content from a new image-sharing website calling itself hai.VL. The name means “funny” in Vietnamese, among other much-naughtier things. The users of hai.VL, which seems remarkably similar to sites like 9GAG, have begun churning out silly trollfaces and template memes. And these images proliferated across the Vietnamese web with astonishing speed, partly because social media is an affirmation of everything a collectivist culture holds most dear. And also because today’s Vietnamese youth, who have come of age in a globalized Internet-connected society, are very different people from their grandparents and their parents. They outnumber them, too. 65% of the current population is under the age of 30.

But there’s another reason. Last year at almost exactly the same moment, as many of you might recall, Facebook introduced a new function allowing users to comment by posting an image with no accompanying text. This changed everything. In a place where the wrong words can land you in jail, there’s a powerful sense of security in being able to express yourself to thousands of people without writing anything. Almost overnight meme culture blew up in Vietnam. Pretty soon hai.VL was giving Google and YouTube competition for web traffic, clones of hai.VL popped up like mushrooms, and the remixers began getting more creative.

Header for the Tuyết Bitch Collection’s Facebook page, ~July 2015

This is the Tuyết Bitch Collection. It’s a Facebook page that was created last August and it now has a little over a quarter of a million followers. The Tuyết Bitch Collection specializes in remixing Disney animated film stills and characters with Vietnamese text and complex references to the social and pop cultural ecosystem. They put up two or three of these a day, riffing on the kind of issues that all Vietnamese youth would be able to identify with. Money, family, love, sex, the lack of sex, current web trends, issues in the news. They rarely engage in overt political talk, but in an authoritarian nation with no civil society, in which every moving part is explicitly controlled by a single party, pretty much everything is political by default. A typical post from these guys gets ten to twenty thousand likes, a few hundred comments, and is shared as many as a thousand times across the Facebook network, and that’s only on Facebook. I know global brands that would kill for that kind of engagement. Tuyết Bitch is two young guys, both with full time jobs, who do this on laptops out of their bedrooms in their spare time.

This all puts me in mind of what Ethan Zuckerman of Berkman Center has called The Cute Cat Theory of digital activism. Among other things that theory suggests that ordinary online tools and platforms, the kind that people commonly use to share innocuous content such as cute pictures of cats make it possible for non-activist users to create and disseminate activist content online. And to me that seems like exactly what’s happening here. I would guess that very few of the young Vietnamese participating in all of this think of themselves as activists with a political agenda. They’re just kids communicating in the way that seems most natural to them about things they find interesting and amusing. The tools of remix and meme culture are by nature innocuous. Most of the stuff from Tuyết Bitch is created in PowerPoint, if you can believe it. How much less threatening can you get than the Ancient Aliens guy?

On the surface it all appears to be just harmless fun and therefore inoffensive to both government officials and, crucially, to other citizens. The medium of the message allows indirect social and political commentary to sneak in disguised as lulz. And it also assures that the content is shared much more widely and viewed much more widely than direct critique would be. In between the two poles of the starry-eyed techno-utopians and the skeptics there are thinkers who’ve suggested that the real potential of online tools for social change in places like Vietnam is not necessarily in coordinating massive street protests and mobilizing activist movements but rather in how they enable citizens to articulate and debate a welter of conflicting ideas throughout society. In other words, social media may matter most not in the streets and the squares but in the myriad spaces of the social commons that Jürgen Habermas called the public sphere. These images and the worldviews behind them are becoming part of the national discourse in Vietnam. And in the process they are quietly, incrementally shifting the zeitgeist.

One more example. Last summer Vietnam’s top health official badly bungled her ministry’s response to a series of vaccine-related infant deaths. This time the remixers drove the online conversation again with a flood of repurposed images.

This one is an imaginary new national stamp honoring the health minister for her service, but it just wouldn’t stick. Online commenters had great fun explaining that’s because people were spitting on the front of the stamp instead of the back. Photos of the Minster—not an especially attractive woman—[were] given a wide, endless variety of satirical captions. The Tuyết Bitch Collection got involved in the fun, not surprisingly. Another version was a mock advertisement which had the Minister endorsing a potent anti-shame cream. A favorite of mine was a “get out of trouble free” card for government officials used in dangerous situations to get out of penalties of all kinds, unlimited usage.

After a couple of months of this a mainstream online newspaper, The Petrotimes, published an op-ed in which they suggested that maybe for the good of the country it might be best if the Minister considered stepping down. This was the first time in the history of modern Vietnam that a state-controlled news outlet had openly called for the resignation of a senior party official. Within a few hours, not surprisingly, the op-ed had been taken down, relegated to the Memory Hole, but screengrabs of that op-ed continued to circulate widely around Vietnam. And at a news conference a short time later, a top party official was asked on the record if he thought that the Health Minister should resign over pressure from Vietnam’s “online public sphere.”

Vietnam is hardly the only place where this has been happening. We saw it just a few weeks ago in Turkey, as all of you probably remember. Artist and Internet commentator An Xiao Mina of The Civic Beat called meme culture “the street art of the Internet.” She’s pointed out that Weibo users in China have for a long time been using Internet memes to circumvent and mock government censorship there. They can even jump the rails of the web and burst out into the real world, where their impact is even more powerful.

It’s often said by way of criticism that these images are amateurish and juvenile and short-lived, and that’s true. But they seem to be achieving what all the finger-wagging from the dissident bloggers in Western democracies has not. They’re changing minds. And they’re doing it so precisely because they are juvenile and short-lived and ephemeral and yes, often silly. That’s the whole point.

As for what all this means for Vietnam’s future well, I think if we’re expecting Tahrir Square or Gezi Park to to break out in Hanoi anytime soon, that’s not going to happen. Vietnam has had enough of violent conflict to last for a very long time. But as scholars like Clay Shirky and Zeynep Tufekci have suggested, perhaps it’s time we stop spending so much time spending attention to the high drama of social media-fuelled protests and instead start considering these tools’ roles in capacity building. It’s also a mistake to consider all of this through the lens of Western assumptions and expectations. A young Vietnamese friend of mine said to me recently, “The revolution is beginning here. But it will happen in a Vietnamese way, not a Western way.”

One more point. Last November, a few months after Vietnam’s meme community went apeshit over the censhorship of Bụi Đời Chợ Lớn and just a year after Vietnam had banned The Hunger Games throughout the country, the second film in that franchise, Catching Fire, opened in hundreds of Vietnamese cinemas without a word from the censorship committee about it being too violent or too anything.

Thank you.

Further Reference

Prior to Theorizing the Web, Patric posted Make Lulz, Not War on Medium, which contains an early version of parts of this talk.