To understand human nature, I focus on human language and what it can reveal about how we think. Unlike other animals, humans can communicate an infinite number of thoughts through language. And one reason that language is powerful is because we can use each of our words flexibly, with several different meanings.

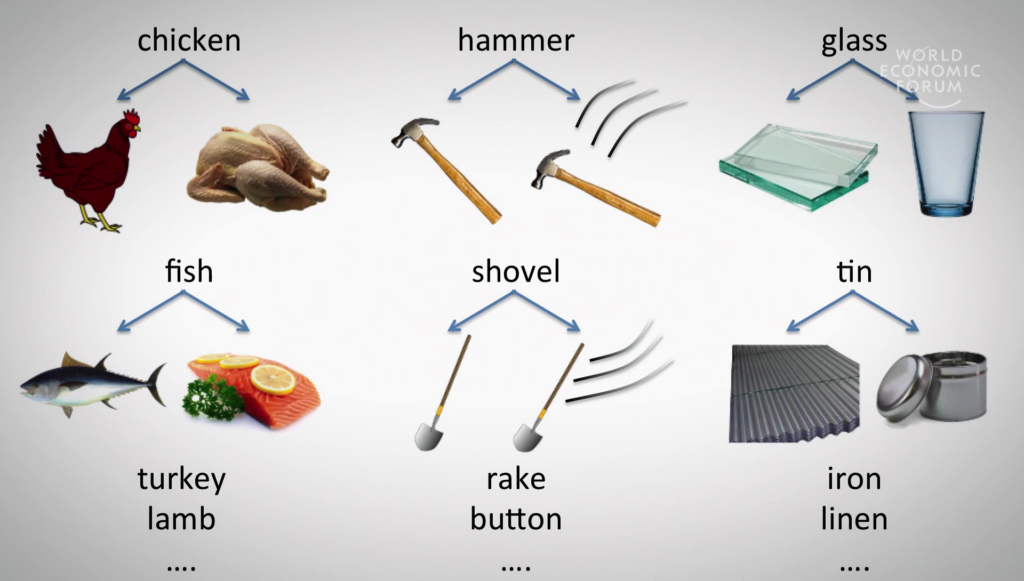

For example in English, “chicken” can label an animal or meat, “hammer” can label a tool or an action, and “glass” can label a material or an object made from that material. And these are just examples of more general schemes through which we can communicate many thoughts using a smaller set of words.

So these schemes reveal how we think, and how we can perceive the very same thing in different ways. So for instance, when we call these chickens “hungry,” we are thinking of them as animals. But when we refer to them as “tasty,” we’re thinking of them in terms of their meat. So in this way, flexible uses of words can reveal how we are construing a particular situation.

By framing our perspectives, flexible words can even shape how we behave. So for instance if we’re told that this patient is “battling” cancer, the language of war might encourage us to consider aggressive treatments for the cancer. In contrast, hearing that the patient is on a “journey” might actually discourage short-term invasive treatments.

So because language reflects how we think, it can reveal how we frame important issues. So by understanding how people around the globe talk about terrorism, climate change, or economic policy, we can better understand their underlying assumptions and biases. And this could lead to greater international consensus.

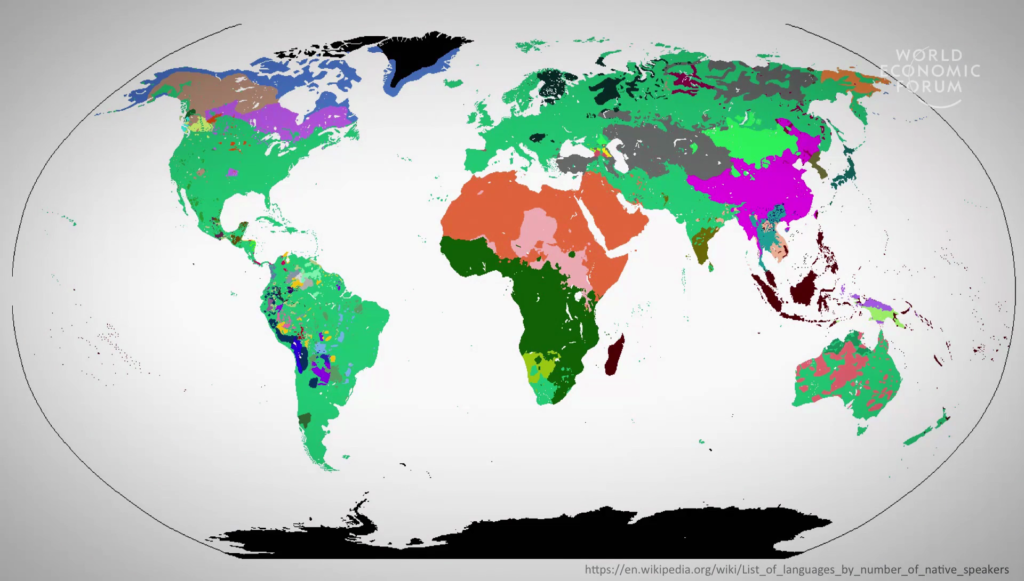

But to use language to reveal different cultural perspectives, we really must first understand how languages vary. There are roughly 6,500 languages spoken in the world today, many of which have distinct lines of ancestry. And so, these different languages could have very different systems of flexibility than English.

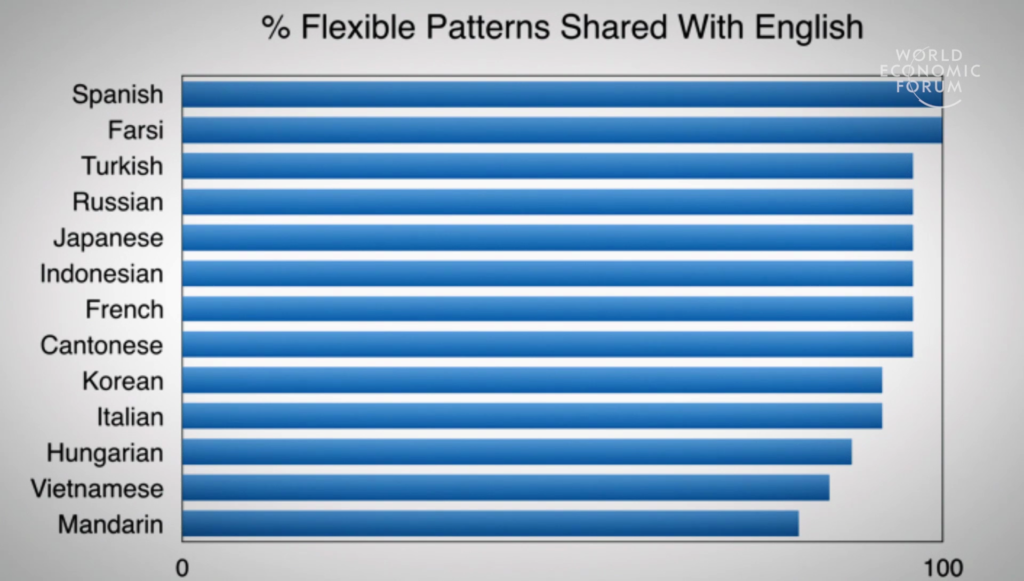

So, interestingly, work from my lab shows that although languages do differ from English in interesting ways, they nonetheless share many of the same patterns of flexibility. This suggests that despite geographic and cultural differences, speakers of all languages may share a common cognitive framework, making it possible for us to understand one another’s perspectives.

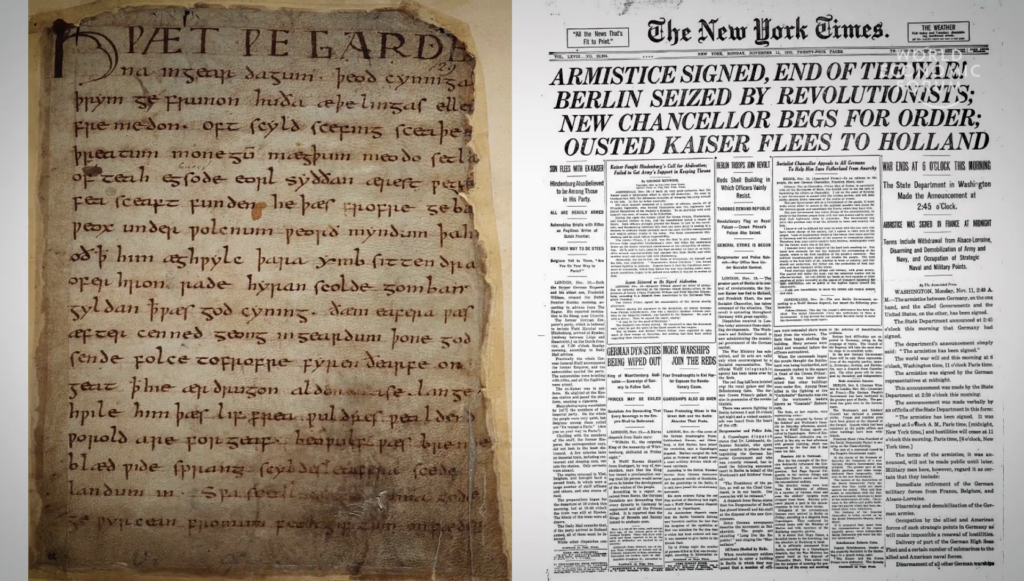

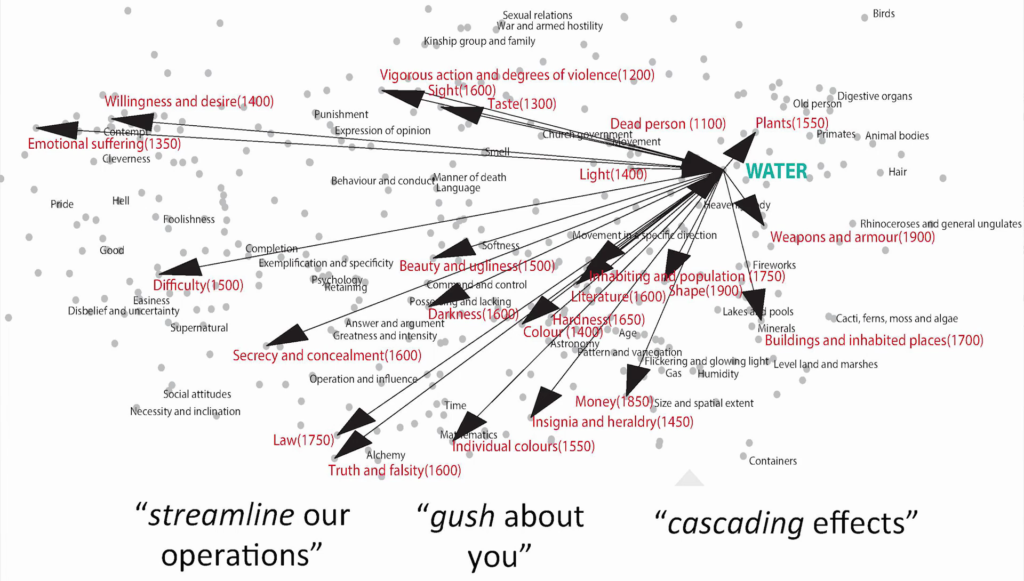

And this cognitive framework, interestingly, is visible not just in similarities across languages, but also in the evolution of a single language. For example work from my lab has traced how English words have developed new meanings through computational analyses of archives dating back a millennium to Old English.

And our models show that words have developed new meanings in systematic ways that could reflect how we think. For example words that described concepts in the external world, like words for water, have been extended throughout history to describe more abstract concepts, as seen with “streamline,” “gush,” or “cascade.”

Now that we see the systematic flexibility across languages and throughout history, we can ask whether this reveals something very fundamental about how we think. And if it does, it might even be present in young children. Even young children might find it intuitive to use words flexibly with these different meanings. And so to study children’s understanding of flexible language, my lab uses eye-tracking technology which monitors where children look as they’re listening to language. So the red lines here indicate where the child is looking.

And this method can give us insight into what children are thinking in real time as they’re listening to language. Using methods like this, my lab has shown that children anticipate the different uses of flexible words from a very young age. So after learning that an action involving a tool is called “daxing,” children expect the tool itself to be called “a dax.” This is similar to how we can hammer with a hammer, or shovel with a shovel.

Our studies show that children understand many of the different patterns of flexibility employed across languages. They creatively use words to label animals and their meats, they use words to label objects and their materials, space and time, and many more. And childrens’ early mastery of these schemes suggests that it might be natural for the mind to link concepts in these ways.

This cognitive flexibility, critically, could be foundational to our sophistication as a species. Our ability to redefine the role of an object in different contexts allows us to see problems in new ways and to come up with insightful solutions.

So to close, the study of flexible language and thought paves the way for many real-world applications. We can better understand the perspectives of one another. We can find ways of promoting children’s open-mindedness and creativity. One day, we could even build artificial intelligence that’s capable of using and understanding creative uses of language. Thank you, and I look forward to discussing this with you all.

Further Reference

Mahesh Srinivasan profile and Language and Cognitive Development Lab at University of Berkeley Psychology

2016 Annual Meeting of the New Champions at the World Economic Forum site