First I just want to say thank you to Addie for bringing us all together for the launch of Deep Lab, and thank you to Golan and Lorrie [Cranor] and Linda and Marge for getting us here and hosting us, keeping us feed and supported while we work. That’s really such a privilege.

This was my plan two days ago, and I’ll be doing something like this. First I just want to give a quick heads up that I’m going to show a video later with a little bit of violence. It’s far less than you’d see on TV, but I don’t want anybody to be taken by surprise, so just fair warning.

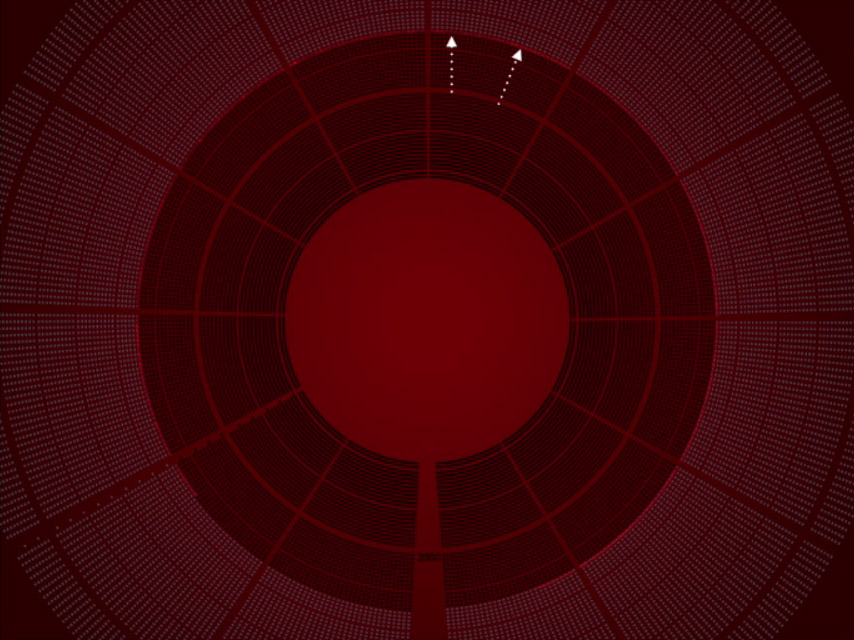

Almost a year ago, I put my heartbeat online, and along with my heartbeat an accounting of all the days I’ve lived, and the days I statistically have yet to live, along with my average heartbeat for each day. So I was playing with the idea of privacy. Here’s this very intimate measure, in a way. But I’m not worried about sharing it because there’s not much you can learn about me from my heart rate.

Screenshot of One Human Heartbeat

But it turned out I don’t know much about heart rates, and you can see starting in mid-July that my heart rate goes up an stays up. So there’s this bright red ring around, and toward the top, the bright red gets much brighter and stays bright all the way until now. That’s because of my pregnancy. Just for reference, the first arrow is around conception and then the next arrow is when I found out I was pregnant. And you can see, maybe not here but in general, that the bright red starts just before that spot.

About two years ago I gave a talk at SXSW with Molly Steenson called The New Nature vs. Nurture and I introduced the Big Data Baby, which was the first baby to be predicted by Big Data, by Target’s algorithms in particular. And in fact the Big Data Baby was born to a teenage mother. And the baby was announced to her whole family, specifically to the father of this teenage girl, by marketing materials that were sent by Target to the family’s address. Our faces are formed between two and three months, and so this Big Data Baby might’ve been identified by data before it’s face was even formed.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wFY_KPFS3LA

Someone else that’s working with data and pregnancy in a more detailed way is Janet Vertesi, a Sociology professor at Princeton, who did a whole experimental project where she tried to hide her pregnancy from Big Data, which mostly meant hiding it from Facebook and Amazon. She often quotes that a pregnant woman’s marketing data is worth fifteen times an average person’s data, so I’m very very valuable to marketers.

But using Big Data to identify pregnancy, I used to talk about that, but I did this project and now it seems to me that that could become antiquated. As more people opt into to pulse-tracking and other forms of bio-tracking, companies will be able to predict pregnancy after just a few weeks, moving the prediction date even further forward to before a woman even knows that she’s pregnant.

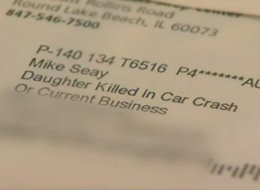

Big Data isn’t just in the business of births, it’s also tracking deaths. Last January, OfficeMax sent Mike Seay this marketing mail, a glitch that shows us he’s in the “daughter killed in a car crash” marketing container. So corporations are using data to announce births and also using data accidentally to remind us of deaths.

I’m going to talk about two future data directions that are particularly disturbing to me right now. And the first is data colonization. This is Shamina Singh from the MasterCard Center for Inclusive Growth. She’s speaking at a data and society event, “The Social, Cultural & Ethical Dimensions of ‘Big Data.’ ” It’s important that you remember that she’s representing MasterCard, and this is going to be about three minutes with some interruptions.

[Transcript of portions played follows video.]

…and the big issue for us is economic inequality, inclusive growth, the gap between the rich and the poor, financial inclusion[…]

[Jen Lowe] And here’s she’s about to tell us the data that MasterCard tracks for each transaction.

It takes your credit card number, your date, your time, the purchase amount, and what you purchase. So right now there are about 10 petabyes, they tell me, living in MasterCard’s data warehouse. In the Center for Inclusive Growth, we’re thinking about how do we take those analytics, how do we take all of that information, and apply it in a way that addresses these serious issues around inclusive growth? Around the world, and we all know what’s happening in Syria, we’ve all heard what’s happening in Somalia, refugees are traveling from their home countries and going to live in refugee camps in safe countries.

Have you ever thought about what it takes to move food and water and shelter from places like the United States? When everybody says we’re giving aid to the Philippines, or we’re giving aid to Syria, what does that actually mean? It means they’re taking water, they’re shipping water, they’re shipping rice, they’re shipping tents, they’re shipping all of these things from huge places around the world, usually developed countries, into developing countries, using all of that energy, all of that shipping, all the fuel, to take all of this stuff to these countries. And what happens? Usually the host country is a little pissed off, because they’ve got a bunch of people that they can’t support inside their country, and they don’t have any means to support them. So one of the things that we have been thinking about is okay, how do we use our information, how do we use our resources to solve that—to help at least address some of that? One of the answers? Digitize the food program.

So instead of buying the food from all of these countries, why not give each refugee an electronic way of paying for their food, their shelter, their water, in a regular grocery store in the home country? But the outcome is that these people, these refugees, who’ve left everything they know are showing up in a new place and have the dignity now to shop wherever MasterCard is accepted? Can you imagine?

[Jen Lowe] I just have to play that again.

…and have the dignity now to shop wherever MasterCard is accepted? Can you imagine?

[…]

Again, working with people at the bottom of the pyramid, those who have least, to make sure that we are closing the gap between the richest and the poorest.

PLENARY — Social, Cultural & Ethical Dimensions of “Big Data”

This is a worldwide plan that MasterCard has, and another worldwide plan comes from Facebook through internet.org, the idea of using drones to deliver Internet to currently-unconnected places. And Google’s Project Loon is the Facebook plan but with balloons instead of drones:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m96tYpEk1Ao

Sometimes everyone isn’t really everyone like when people say everyone’s on the Internet because the truth is for each person can get online there are two that can’t and when you look closer, that everyone looks even less like anyone[…]

“Introducing Project Loon”

If you see a video with animated string and a little girl’s voice, that’s a sign that you might be terrified. So, really for me these three things come together—MasterCard, Facebook, Google—to represent what might be the complete remote corporate colonization of the dark places on the map that’re being wrapped up like a present.

The second data direction that’s disturbing and particularly timely in the US has to do with three things I see (I’m sure there are more) going on together with policing in the US. Predictive policing, militarized police, and also something that’s very specific and new that I’m calling “protected police.” Predictive policing is actually happening in Chicago. The Chicago Police Department was funded two million dollars by a Department of Justice grant. They used an algorithm and data to create a “heat list” of the 400 people that they predicted to be most likely to be involved in a violent crime. There’ve been Freedom of Information Act requests for that list, but those have been denied. And particularly important I think is that sixty of those 400 people have been personally visited by the police. Basically just to say, “You’re on this list and we’re keeping an eye on you.” So precrime is sort of real. And another thing that’s particularly disturbing about that story is that the researcher involved uses this kind of language. He

assures The Verge that the CPD’s predictive program isn’t taking advantage of — or unfairly profiling — any specific group. “The novelty of our approach is that we are attempting to evaluate the risk of violence in an unbiased, quantitative way.”

The minority report: Chicago’s new police computer predicts crimes, but is it racist?

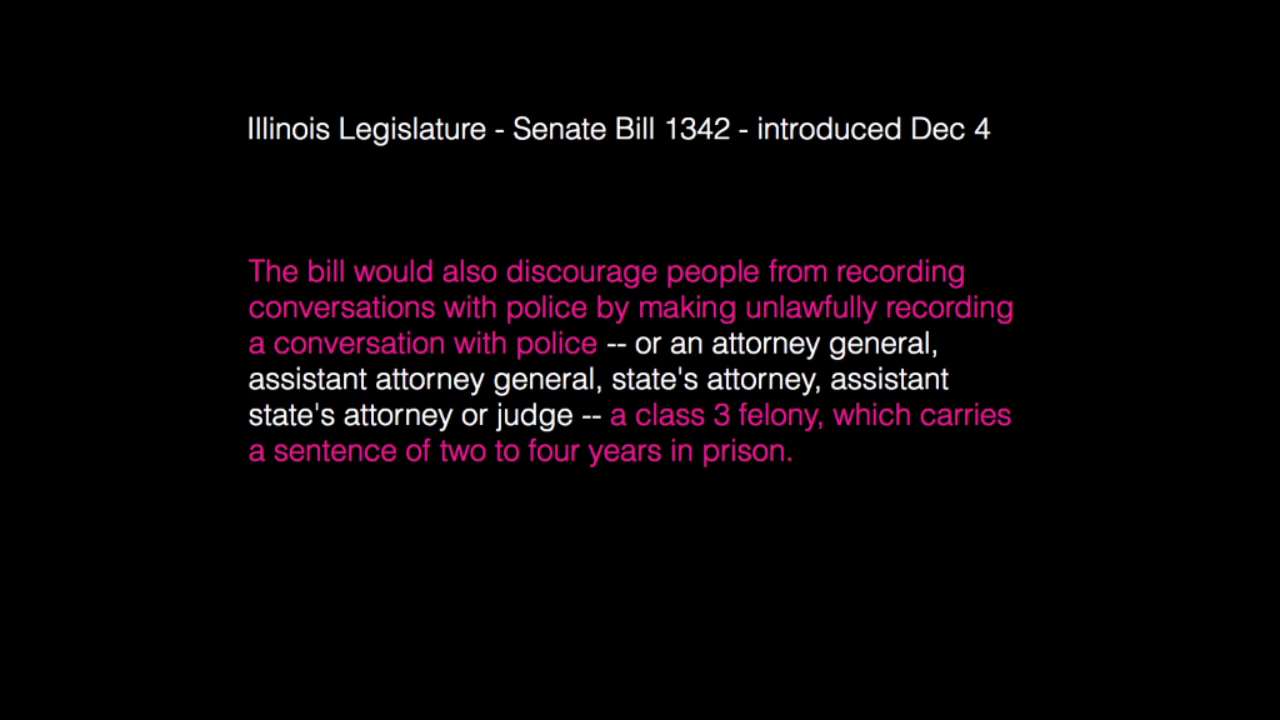

Don’t ever trust “unbiased” and “quantitative” put together. So that’s happening in Chicago, and the Illinois legislature just December 4th [2014] introduced a bill that basically makes it a felony to videotape the police up to a sentence of two to four years in prison. So in Chicago if you add this together what it ends up meaning is that police can use all data available to them to predict citizens’ actions, but citizens can’t collect data on the police.

So now that we’re totally depressed about data colonization and trends in data policing, I’m going to use a little Nina Simone to revive us. In case you miss it, the interviewer asks, “What’s free to you?”

[Transcript of portion played follows video.]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Si5uW6cnyG4#t=74

–Well, what’s free to you?

–What’s free to me? Same thing as to you, you tell me.

–I don’t know, you tell me. Cuz I’ve been talking for such a long—

–Just a feeling. It’s just a feeling. It’s like how do you tell somebody how it feels to be in love? How are you going to tell anybody who has not been in love how it feels to be in love, you cannot do it to save your life. You can describe things, but you can’t tell ’em. But you know it when it happens. That’s what I mean by free. I’ve had a couple of times on stage when I really felt free, and that’s something else. That’s really something else. Like all, all, like, like, I’ll tell you what freedom is to me. No fear. I mean really, no fear. If I could have that, half of my life, no fear. Lots of children have no fear. That’s the closest way, that’s the only way I can describe it. That’s not all of it. But it is something to really, really feel.

–Have you… Like, I’ve noticed…

–Like a new way of seeing. A new way of seeing something.

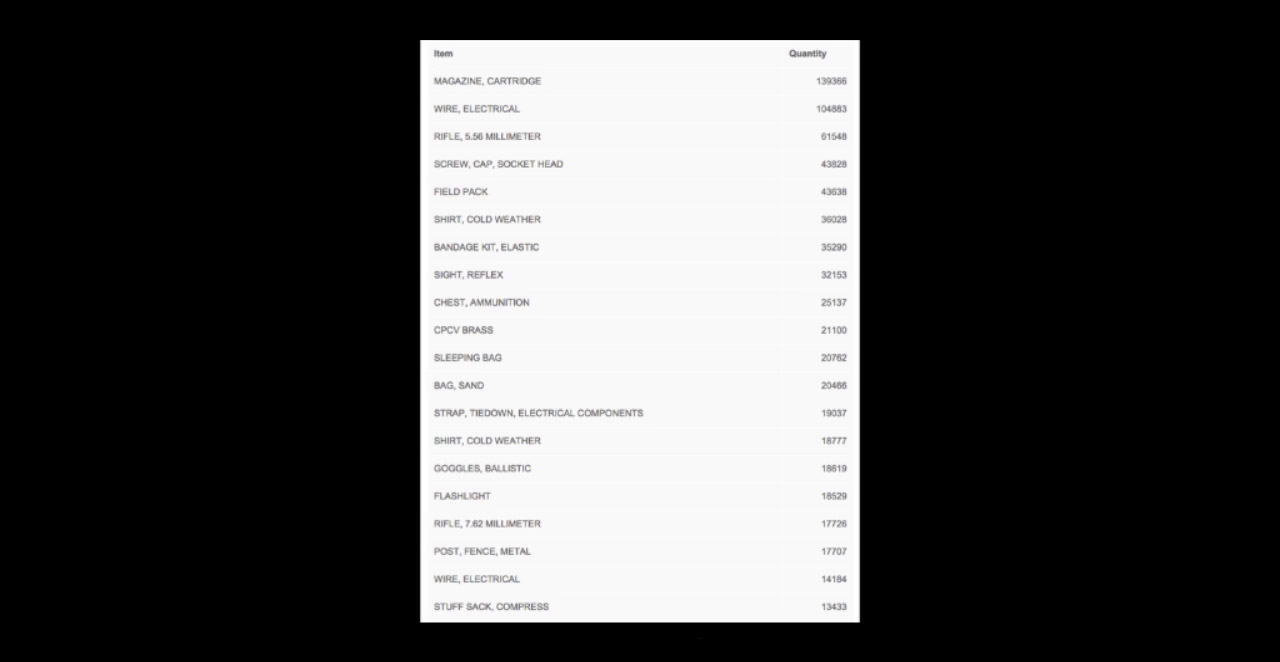

So if freedom is no fear, it’s safe to say that we’re pretty far from that right now. The Pentagon’s 1033 program, which provides transfers of surplus Department of Defense military equipment to state and local police without charge is creating this police militarization. And during this week, Ingrid Burrington has been working with the data from this 1033 program. This is a list of the most common items provided free to police in the US, and the data’s available online, if anybody feels like working with it:

Sample of data from https://github.com/TheUpshot/Military-Surplus-Gear

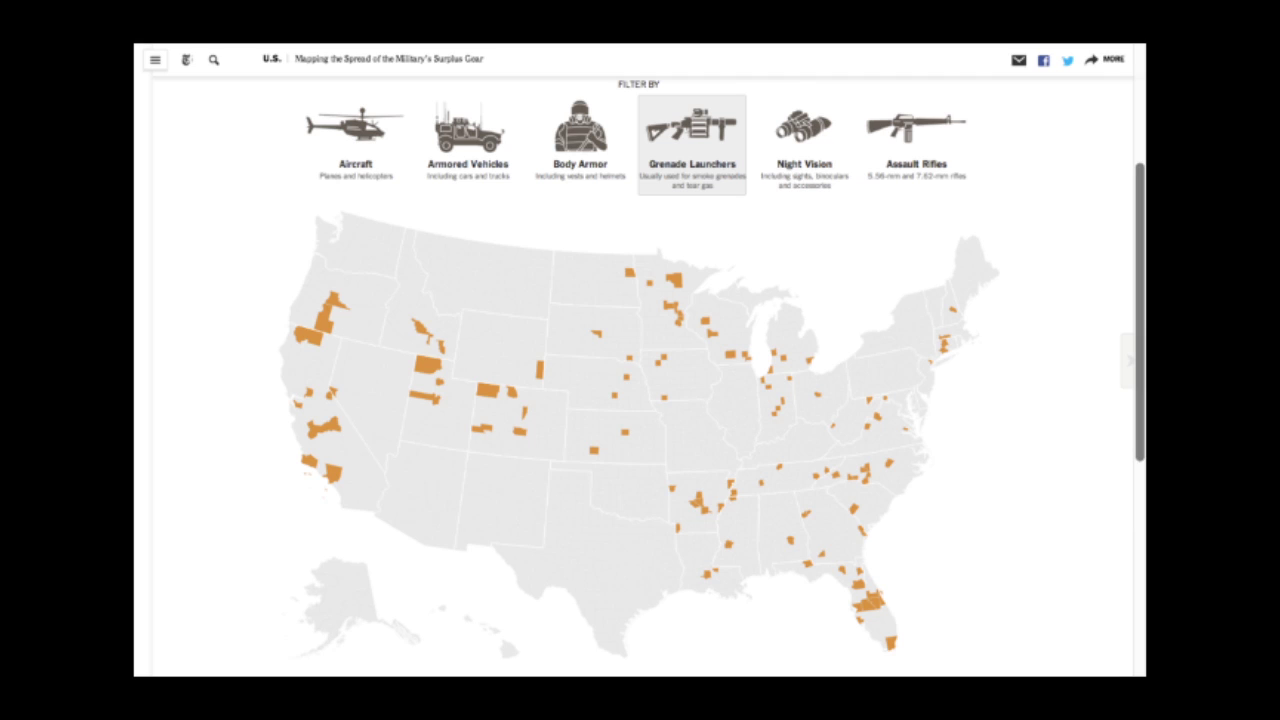

The New York Times has a nice visualization of the location of various giveaways from this 1033 program. Here you see the 205 grenade launchers that have been given to police, and where those went:

Grenade launchers are primarily used for smoke grenades and tear gas. And tear gas is a really personal thing for me right now because it causes miscarriage. So there’s been all these protests in New York, and I’d love to go out and take to the streets but it’s not something that I can do right now. And I feel very much because I know that if I went out with my friends they might be able to protect me but there’s no protection from something like tear gas.

I think about this Turkish woman all the time when I think about protest. And I think about the Standing Man in Turkey who started this protest by silently staring at his own flag.

And I’ve been sort of, not towards any purpose, but reading a lot about silence over the last year. This is from Sara Maitland’s Book of Silence.

We say that silence ‘needs’—and therefore is waiting—to be broken: like a horse that must be ‘broken in’. But we are still frightened. And the impending ecological disaster deepens our fear that one day the science will not work, the language will break down and the light will go out. We are terrified of silence, so we encounter it as seldom as possible.

Sarah Maitland, A Book of Silence

This is Ernesto Pujol’s work. He’s a performance artist who creates site-specific works that use walking, vulnerability, space, human energy, and silence as his materials. I’m going to read from his 2012 book.

The performance begins to reveal how time is an incredibly elastic construct. As the performers stood still, walked, and gestured slowly for twelve hours, their silence became an entity that heightened not just their own but everyone else’s awareness, slowing down everything and everyone, filling and sensorially expanding the dimensions of the room, it’s height, depth, and width. The silence emptied the room of noise, it rejected noise, filling the room itself, as tangible as liquid, as if the room was a water tank. Silence did not create a void. It had a tangible body we could cut through with a knife. Our Chicago public, unexpectedly found silence again. A silence that human beings need to sustain the human condition for listening, remembering, reflecting, discerning, deciding, healing, and evolving. Silence is a human right.

Ernesto Pujol, Sited Body, Public Visions

This came out super-recently and it’s an example of silence stopping a fight on a New York subway. Watch for the snack guy:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Erlw-ODVZxU

So this guy comes in and without a word or even like a gesture or an expression, he’s just silently eating his Pringles but successfully breaking up the physical violence of this fight that’s going on.

So we’re here this week working on projects related to privacy and anonymity and the deep web, and I noticed that this weird thing happens when I talked to people about coming here. It’s that when I mention that I’m doing something about the deep web, people I know, their immediate response is like, “Isn’t that just a thing that’s for child porn and human trafficking?” And I also happen to be from Arizona. And I’ve noticed it’s almost the same sort of response. When I say I’m from Arizona people immediately say something about how racist Arizona is. And so these seem to me that they’ve become these sort of shadow spaces to be avoided.

And to be clear, Arizona has a lot of issues. In 2011 there was a mass shooting where eighteen people were shot and six people died. In 2002 three nursing professors were killed on the U of A campus in Tuscon, actually while I was teaching. The Oklahoma City bomber developed and tested his bombs while living in Arizona. Two of the 9⁄11 highjackers took flight lessons in Arizona. It took Arizona voters three tries to pass Martin Luther King Day as a holiday, from ’86 to 1992 when I was a kid. The state lost hundreds of millions of dollars to boycotts. Stevie Wonder refused to perform, the Superbowl pulled out. I remember from being a kid that the defense at the time was money, that the state couldn’t afford another state holiday. So when the holiday finally passed and they had to have it, they took away Columbus Day, which was a lovely sort of balance. And this is just the video for Public Enemy’s “By the Time I Get to Arizona” which sort of chronicled that fight to get Martin Luther King Day in Arizona.

Arizona also has a long history of racist policing, especially when it comes to border issues. Teju Cole has this very excellent Twitter essay about the Arizona/Mexico border. In 2010 Arizona passed a bill that requires immigrants to carry proof of their legal status and also requires police to determine a person’s immigration status if they have a reasonable suspicion that that person is an immigrant. So that law basically demands racial profiling from the police.

But other things grow in these shadow spaces like Arizona. The Sanctuary Movement started at the Southside Presbyterian Church in Tuscon, Arizona in 1980. And it provided housing and other support for refugees from Central America, especially El Salvador and Guatemala. It expanded to include over 500 congregations nationwide. I don’t think it’s well-known but it really was the Underground Railroad of its time. A friend of mine in grade school had a Guatemalan family secretly living in his house, which he didn’t tell me until we were in college.

There aren’t many images of this because providing refuge and sanctuary are by necessity quiet acts. In researching this talk I found that there are new Sanctuary movements popping up again all over the US, again providing refuge to immigrants. No More Deaths and Humane Borders are two Southern Arizona groups that primarily care for immigrants by the simple, quiet act of putting water in the desert. Members of both groups have been prosecuted for leaving water and driving immigrants that are hurt to the hospital. So carrying water into the desert and driving dying people to the hospital become dangerous acts.

The Dark Web and anonymity on the Internet are popularly seen as shadow, criminal spaces. People say, “Why do you need to be anonymous? You have nothing to worry about if you have nothing to hide.” But I learned that in Arizona, that in the shadows and in anonymity there is power, that the Wild West is a good place for making silent but revolutionary change.

Still from Black Mirror, “15 Million Merits”

This is an image from the second episode of Black Mirror, which is not me encouraging you to watch Black Mirror, necessarily. It’s…you’ll need a therapist if you are going to watch the show. But in this particular episode Bing, who’s the character pictured, ends up being richly paid to perform the voice of dissent. Two years ago I was doing this insane five-day drive across the country, and it was just me and my dog and I was moving from California to New York. And I stopped the day after Christmas in Albuquerque to meet with my friends Shaw and Rachel. Rachel and I had just spoken together at this Big Data marketing conference, and we were very much playing to role of the voice of dissent. So we were talking ethics when we were supposed to be talking money. Everyone else was talking money. And I said to them, “I feel like when we show up and we give these dissenting talks from money (we get paid for giving these) we’re like holding the glass to our throats.” I feel just like this Black Mirror episode. It’s a performance. It makes power feel like they’ve earned their badge for listening to our dissent. But what does it change? And they asked, “Jen that’s nice, but what do you want to do instead?” And at the time, I said this:

I’m thinking about how to become more dangerous.

This seems really complicated. It seems like how do I become more dangerous compared to this world where these giant corporations are using Big Data, and now I feel this sort of, how can I become more dangerous when I can’t even go out in the streets and protest, because I don’t want to be around tear gas? But I increasingly think that, for me, and maybe also for you, becoming more dangerous can mean finding a quiet gesture that helps us to create less fear and more freedom.

And this works in all spaces, offline and online. But online spaces strike me as these particularly rich spaces for these sort of invisible gestures. And some of the work that’s being done this week, Harlo’s Foxy Doxing project which provides more information and context about abuse online, Maddy just described her Safe Selfies project which gives individuals this aggressive power to protect their own files. Also I can think of when individuals just fill in OpenStreetMap data in areas of humanitarian crisis or natural disaster to help aid workers find their way. And related to why we’re here and the future of this grant right now, Julian Oliver and Danja Vasiliev’s work teaching people how to use Tor and other tools for anonymity.

So as we go forward as a collective I think about how we might become more dangerous. For me becoming more dangerous means answering: how might I offer sanctuary in the midst of uncontrolled monitoring of our behavior online, of the commodification of consciousness; in the midst of data colonization and predictive policing? How can I build refuge? And becoming more dangerous means answering in the midst of all these hostile off-line and on-lie environments: how can I carry more water? Thank you.