Hi. I’m going to give a talk this evening about what I like to call activist metadata. First off, I’m Harlo. I currently work for a group called The Guardian Project. We build primarily mobile (but not entirely) software that is built for circumvention technology, and our clientele—well I mean everyone, we want everyone to use the apps—but we also do a lot of hands-on support for journalists, legal clinics, human rights activists, and other do-gooders all over the world. I also just finished a fellowship at the New York Times sponsored by both the Mozilla Foundation and the Knight Foundation, which are both large supporters of the press. And I worked with the computer-assisted reporting team on their workflows of documents.

My research interests right now are and have been for the past couple of of years are in metadata. And that’s a really really sexy word right now, so: What’s metadata? I Googled it. I Googled it. Okay. So “there are two types of metadata, structural metadata and design metadata” or whatever. Actually metadata is data about data. Data that describes the data that you’re looking at. By way of illustrating what metadata is I decided to actually go to the image search because this is what metadata is. You will get the answer to your question via being around the question and seeing what kind of data pops up to the fore.

You’ll notice that one of the most popular associations with the term metadata, because it’s been pushed to the forefront of the Google image search is “NSA.” And of course living in the post-Snowden world, you guys all understand exactly how this word got associated with the NSA in such a way that it was pushed to the top of Google’s image searches. So that’s a very very interesting way of thinking about what metadata actually is.

So how can it be activist‑y? I’ll give you a couple of examples. This one I really really like by a journalist from Reuters called Megan Twohey, where she investigates these illegal exchanges of adopted children in the United States via advanced searches on Yahoo! Groups. And she was able to call a lot of this data in an automated way, massage it using data-scraping techniques and natural language processing in order to paint this picture about how children in our country are just being tossed around from family to family like you would a car or a used Prada bag or something like that.

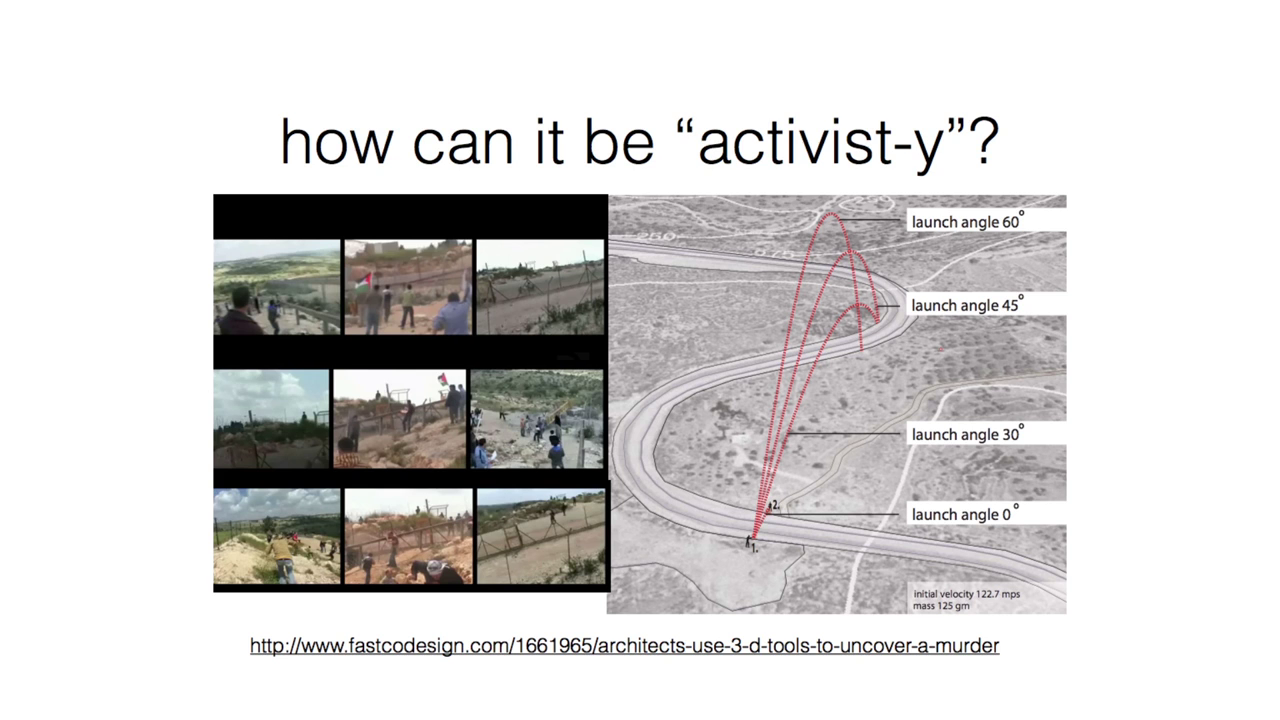

Here’s another example that I love from a group called SITU Studios out in London. This is an analysis of ballistic forensic analysis of an event that took place in the Palestinian region having to do with a protest. A protestor was shot by an Israeli soldier, and the culpability of that soldier was eventually proven via forensic analysis of the video of that protest event that was taken haphazardly from three different angles. And then SITU Studio, which is actually an architectural firm, took those three videos and were able to prove culpability based off of the image metadata captured inside the videos alongside with matching up audio, matching up camera angles, and things like that.

These are really really excellent, excellent examples of activist metadata. However these examples are kind of few and far between, for a couple of reasons, and actually that prevents them from being activist‑y. I’ll tell you why. The ballistic forensic information, in order to achieve that particular domain knowledge actually takes a lot of study. It takes a lot of investment to actually peruse the scientific journals that aren’t necessarily open to you because you don’t have the domain knowledge and you’re not part of the university system, or whatever barriers are in your way that prevent you from achieving this domain knowledge and put[ting] it to data.

Also there’s a kind of stereotype of the nerd once again. When you google a nerd, there you go. When you Google that profile (Google of course being the absolute unmitigated truth) that profile doesn’t necessarily match the profile of those who are sitting in human rights organizations, or in press outlets trying to answer these questions.

Another thing that stands in people’s way is money. And there’s a system that works on a lot of these domain-specific questions in an elastic way called Palantir, which is a really really great program, however it’s incredibly expensive. It’s not open-source, despite the fact that they use the terms “open” and “source” so much on their web sites, it’s not. It’s a very closed-source program. The “open source” that they talk about is the data that they pull down from it and work on. That said, what we decided to do was to find a way to answer questions using metadata, creating tools that were elastic enough for people to use under any scenario they can imagine that kind of looked like Palantir but was 100% open-source and for the people.

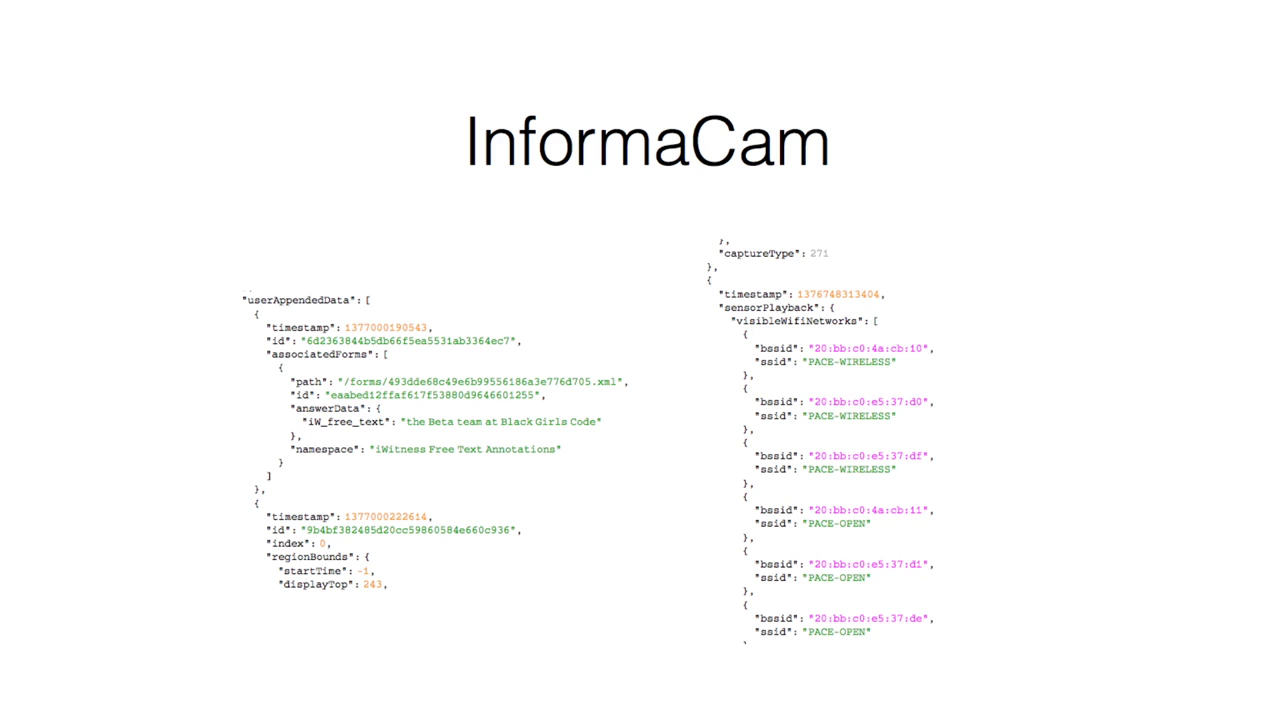

This started out with a project that I started with The Guardian Project, an organization called WITNESS, and the International Bar Association called InformaCam. It’s a horrible name and I’m very sorry. But, for instance, you take a photograph or a video and we all are aware of EXIF data but we decided that we were going to add a whole bunch of extra metadata. So in addition to your EXIF data you also have your accelerometer data, so the way that you actually hold the device as you’re taking a photo or framing your perfect shot. We also sample things like light meter values, because that actually corroborates any story you might tell about what time of day it is. Geo is latitude and longitude, that’s kind of old. We decided that we could better corroborate location by adding extra data points such as visible cell tower IDs, visible wifi devices, and stuff like that. I’ll tell you an interesting story about the wifi devices. But we also allowed people to add in human-readable bit of data. So in the protest example, you can say, “That’s the policeman that shoved me.” or whatever. And all of this information was then taken and imported into a program that I’ll talk to you about very shortly, and made automatically indexable and searchable. So you could actually run Google-like queries, that say “Show me all of the photos that were taken on the Brooklyn bridge around this one particular cop in the area.”

In our initial experiments with this particular program, we actually kind of noticed that—and you’ll see on the right side of this screen—we have some wifi networks. I unfortunately don’t have a picture of it here, but we started to notice that a lot of those BSS IDs, which actually correspond to routers that you might see in a room, were showing up as all zeroes. What that means is that you probably have a case of IMSI catchers or “StingRays” or something like that on your hands. So that became an interesting data point, to say like “show me all the protest photos where there was a Stingray.”

We built a couple of versions of this, one being the version that we built for the International Bar Association that is a little bit more streamlined. In addition to taking all that metadata, you are able to tag stuff and say “that’s the victim, that’s the perpetrator” or whatever. That was indexable and searchable. We also built a version of it that had a simpler and more graphically-intensive interface for a legal clinic in the Southern United States, for migrant farm workers. So they could actually take selfies to check in at work, and if ever a farmer said that So-and-so was not working seven hours on this farm, he was only working six, we could actually show them the metadata and say that you’re going to have to pay this person for the work that they did. This app also allowed people to take incident reports for on-the-job safety violations, and also took track of how long their lunch breaks were so we could file more long-term, further-reaching reports.

The software that we use to pull down and make use of all this data is our open-source version of Palantir, which I call Unveillance. It’s kind of like a mixture of Palantir, which I described before, and Dropbox. So you can just take a group of files, dump them in your folder and then in the background, just as Dropbox does, it performs calculations on the documents that you put into this folder, and it allows you to take that data from those calculations and massage them into whatever questions you might have to answer. Working with The Guardian Project and the New York Times, I was able to bring this about, and I started to use it to answer some more questions, because what good are you if you’re not trying to muckrake, right?

So I thought about the recent group of documents that came out of Darren Wilson’s grand jury trial, and how there are a lot of really interesting reports circulating about how the officer’s perception of Michael Brown colored the way colored the way that he treated him, and having to do with his size and his race, and how that gave him the illusion of a more dangerous suspect. So I put the grand jury testimony data through some accelerated test searches using the Unveillance engine having to with how they talk about this man’s size. And this is a little video here where we’ve done some topic modelling based off of the search terms that we had here.

[Over the next paragraph, Harlo is talking over a block of video running from approximately 12:00 to 13:40. Inline timestamps are linked to screenshots of some specific references, for context.]

[12:29] Down at the bottom we have groups of subjects that come out of natural language processing that inform where in these various parts of the depositions people are talking about his size and how they’re talking about his size. And we noticed that a lot of these things are usually linked to drugs and a paranoia that this is a crazy person on some sort of hallucinogenic drug or whatever. And so we were able to then search deeper within the corpus of documents. [12:50] That pink document, number 5, is Darren Wilson’s testimony himself. The OCR-ing, which is how you use optical recognition in order to get text out of PDF documents is a little bit imperfect, so our engine allows you to edit that if you need to and then run those processes again. But this is the unedited document. And then finally we come to, this is once again the grand jury testimony of Darren Wilson, [13:20] able to run this through more natural language processing where we can map certain terms, like “marijuana” and “gun” and stuff like that, and his largeness or whatever on to specific parts of the document, [13:36] in order to draw certain conclusions about stuff like that.

So where next? Something that I find interesting (This is a project that we’re working on this week with the help of some of the other speakers that you’ll hear from tonight and the other evenings), [we’re] working on a project called Foxy Doxxing, which is inspired by this interesting case that came out a couple of weeks ago, maybe two weeks ago, about how a woman who had been attacked on Twitter by you know, “the trolls” decided to take forensic analysis into her own hands in order to find out who was attacking her online. What I find interesting about this particular scenario is that the woman here, she’s a security researcher who works for the Tor project, so she’s incredibly technically savvy of a developer, as you can imagine. And the tools that she had used, and the techniques that she had used, are not necessarily available to anyone who might seek protection. Unfortunately what I’ve come to learn from working with several newsrooms and speaking to several journalists, particularly women but not always, is that there’s a huge disconnect between…actually there’s no technical capability at any of their newsrooms to protect them from these particular threats. And that’s kind of sad, given that this one particular security researcher was able to fend for herself and find her attackers, yet you go to somebody who works for the Washington Post and she can’t do anything. The Washington Post can’t do anything. So that’s where we’re going next with this particular engine.

And so the strengths and weaknesses are, as I was mentioning domain-specific knowledge before. Like that forensic ballistic example. I personally didn’t spend decades researching natural language processing. I don’t plan on spending much more doing natural language processing. But because this engine that we’ve created is open-source, it actually runs on gists on Github from specific users. So if someone who has more domain-specific knowledge than I do looks at my little snippets of code that run those integral pieces of programming and says, “Well, you know you might want to change that.” they can submit some sort of edits to Github and if I accept them and run the documents through the processes over again, we can actually get better at analyzing things, together.

And that’s it. So thank you for listening to my little show and tell. Thanks.