Hi, good morning. It’s nice to see you all here. So, what I want to talk about is what may seem like a rather boring topic, institutions. Why we not only continue to need them, but also why I believe that each of us, with our sort of new values, should be actively contributing to creating the institutions of the future.

So, if you look at human history all the way through, we organize ourselves in different ways. Tribes, religions, guilds, states, more recently companies and networks. And what these institutions do is they sort of codify values and beliefs, and then they transport them across the generations. So we see this phenomenon that when you codify values in institutions, you give those values longevity.

This picture is a professional guilds of glaziers, people that work with glass. And for hundreds of years, they’ve been sort of conservatively managing their own professional values about how you work with glass, and they share that with people that come after them. It’s the same with accountants and lawyers. Today there’s a lot of pressure on professionals to sort of cut corners, to hide cheating in companies, to sign off accounts which are actually quite dodgy. But these people have professional values and standards built into their institutions that actually are supposed to prevent them from doing that.

Now, sometimes institutions can actually play a really important role in protecting values during hard times. This is an article from a former head of the BBC, and what he points out is that today when the BBC is really under attack by a conservative government and by commercial interests, nobody really wants, in the commercial world, to see the BBC being strong. And if it was destroyed, it would never be invented again. And yet the BBC is probably the greatest custodian of the liberal sort of multi-ethnic modern values of the UK, much more so than even the state. So you have a great example of a very old, very conservative, quite bureaucratic and old-fashioned institution that somehow manages to protect a notion of public interest and public service broadcasting that the commercial sector and even the government really would never create today.

Now, it’s interesting. You know, we can be very critical of companies, we can look at them and think they’re all sort of bad. But if you look at some of the oldest companies, and there are companies in existence today that go back to the 7th century and the 6th century, you know. There are some very very old organizations. But what the oldest ones have in common is that they have nurtured their ecosystem.

But in America, perhaps Lloyd’s most famous moment came as a result of the San Francisco earthquake of 1906. After the earthquake, Lloyd’s underwriter, Cuthbert Heath said: “Pay all of our policy holders in full irrespective of the terms of their policies.” This message has since passed into insurance legend, because the San Francisco disaster cost Lloyd’s dearly — more than $50 million — a staggering sum in those days, the equivalent to more than $1 billion in today’s terms. Lloyd’s faced an enormous bill. But they honored it, and Lloyd’s good faith was soon rewarded.

Rachel Brown, “5 Of The World’s Oldest Companies”

This is Lloyd’s of London, formed in 1688 in a coffee shop, through a network of people that wanted to improve shipping. And one of the really interesting things about its history is that in the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, it faced ridiculous levels of claims. And actually, if it did things by the book, it was able to not pay out on lots of those claims. But they said, “You know what? Screw it. Pay everybody,” and it cost them the equivalent of like a billion dollars today. But what it did was it built trust, and it protected the ecosystem around Lloyd’s of London that would otherwise have collapsed in the face of those claims. And so it continues today as a successful institution.

But the problem is that in the 20th century, we’ve built these sort of castles, these corporate castles, with thick walls, barriers to entry, preventing other people from competing with them through the sheer size, and scale. And then what we did, within those organizations, is we built rigid management structures, rigid bureaucratic hierarchies. And so these company then optimized in these vertical silos to deliver something that wouldn’t change. And as a result, by the end of the 20th century many of them are really struggling because things are changing, and things are changing a lot more quickly than they’re able to cope with.

So I think an interesting question is if bureaucracy was the platform for the Protestant work ethic period of bureaucratic management, then what is the platform for the future? And this is where I think you guys have a really important role to play.

So first question, why do I even need institutions? Surely we’re all hipsters now, in coffee shops with our startups and our devices and all sort of craft coffees. Well, I think we do. And I think the first reason why we need them is that actually, the world of startups is not as rosy as it might seem. We’re building startups whose goal is to die. They want to flip, they want to be destroyed by bigger corporate interests or by investors. And effectively these startups are sort of a financial product. They’re being traded, bought and sold.

This is a flyer that was put up around Palo Alto, aimed at Palantir workers. Palantir is a massive, absolute mega sort of modern corporation that’s developing there. They rent half the city’s office space, I think. People are saying, “Look, you guys have been fooled. Actually your common stock is worthless. All of the value is accruing to the owners of that company, not to you the workers or those involved.”

And I think another challenge is that if you look at where we’re going now, it’s not all apps. You know, we can’t live by apps alone. We also need hardware, we need physical goods. And so we’re seeing a shift from the virtual world back to the real physical world. And what that needs is the engineering skills of Finland, and Germany, and Italy, and the sort of European tradition of how to make things really successfully.

But connected products need connected organizations. And this is why I think we really are in need of a fairly radical reworking of of the institutions that we operate in today. Bosch is a superb company. They make billions of sensors. Their sensors are probably all around this room today. They are superb engineering. But they’re so optimized into these individual product lines that they find it challenging to build lateral connections across them, which is what you need for the connected car, the connected factory, and the connected home.

Now, we do have some emerging corporate institutions of the 21st century, what Bruce Sterling calls “The Stacks,” Amazon, Facebook, Apple, Google, and so on. But these are not the droids that we’re looking for. They are successful. They have created in some cases very successful ecosystems. But they are really not a model for the 21st century institution.

So, the question is what might the characteristics of a 21st century institution be? And I’m just going to really race through a few of these. Obviously it’s networked. Networks are the new value chains. They’re the new protection. Not the sort of castle walls that we looked at before. But I think they’re also lateral and layered.

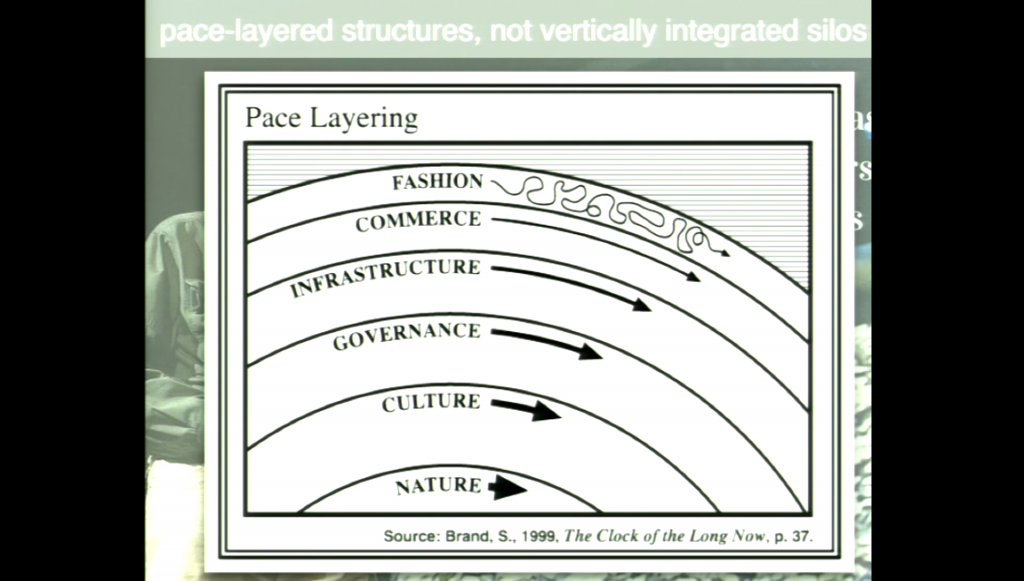

“The order of civilization. The fast layers innovate; the slow layers stabilize. The whole combines learning with continuity.”

Stewart Brand, The Clock of the Long Now

You may have seen this guy Stewart Brand, a really great thinker in California. And he talks about the fact that all civilization is built of these layers that move at different speeds. So, at the bottom of the stack, nature changes very slowly, our culture and our governments change a little bit more quickly. But if you look at the top of stack, areas like fashion and technology and content and so on, that changes very rapidly. And we need to reflect this in our organizations. Just as software used to be very vertically integrated from top to bottom, now software is a collection of microservices and services and data layers and APIs. And they all move and change at different speeds. And that I think is a really good architectural model for the organizations that we’d like to see.

We need also to be service-oriented. If we have loads of teams who are developing different things, or people doing different functions, instead of managing them through a sort of bureaucracy going up and down hierarchies to get things done, we need pier-to-pier, service-oriented relationships. So, you know that this team makes X, and this team makes Y, and they can work it out between themselves. This is a drawing [not shown] by a friend of mine Dave Gray, whose book The Connected Company is a really good study of how this stuff works in the real world.

We also need to be platform-based. And that doesn’t mean Uber and Airbnb, necessarily, where all the value is captured at the center. Amazon is a brilliant example of a platform business that also develops ecosystems based on its own needs. But actually the probably the most interesting ones are in China. So things like Alibaba, and this company called Haier. Haier used to be a state enterprise. It produced really poor-quality goods. And this this guy, Zhang Ruimin, sort of changed all of that, first of all by inverting their hierarchy. So he said, “Okay, if you are more than three steps away from a customer, you’re just sort of support staff. You’re like an admin person.” And so suddenly all of the management talent sort of runs to the edges of the organization and works with customers and markets.

But his next and more radical transformation was to turn the company itself into a platform. So each individual department of this company is now a micro-enterprise, and they work on a common platform that Haier has created. And the next logical step beyond that is obviously that they can open that up to other companies to operate on their platform. So that’s a true platform ecosystem play, and I think a very interesting one of to study.

We need distributed organizations. Small teams, eight to twenty people focused on a single thing, joining together in much more imaginative structures, rather than just hierarchies. We need them to be self-managed. We used to think that automation and technology would threaten the lowest-level jobs. But actually I think the biggest threat from automation is middle management. It’s people whose job is to operate the bureaucracy, to move information from one place to another, and to tell people what to do. Well, you know, that’s something that computers are actually pretty good at. So I think we will see a replacement of lots of management by sort of algorithmic management and real-time data flowing around organizations.

I don’t know if this word exists, but I sort of feel it should. We need cyberorganizations. We need sort of cyborgs. In other words, a happy relationship between machines and people. We used to think artificial intelligence was all about replacing human intelligence, but now we realize it’s about augmenting human intelligence. It’s about creating environments where the skills, the values, the sort of instinct of humans can operate more freely.

This is an example [not shown] of a factory where you have the sort of friendly co-bots operating alongside people, not taking away the skilled work, but doing all the basic stuff that people don’t really want to do.

We need a level of sentience in organizations. Because we are connected with our social networks, we have this human sense in that work. It’s the basis of what could be a sort of democratic system within organizations, where people can tell you what needs to happen. They can give you feedback, they can tell you what’s broken, what needs fixing, what’s not working so well. And we need to use that, and we’re not using that today.

And I think we also need self-aware organizations. Before coming on stage, I look at my Apple watch to see how ridiculously high my heart rate is because I’m nervous. And I can actually get my heart rate down by looking at this this data. We also need quantified organizations. We need to understand what makes up a healthy organization. And we need to grab the data and the feedback to monitor that, so that organizations can have a degree of self-awareness that can lead them to transform in new and interesting ways.

They probably also need to be agile. We used to think that the way you manage an organization is that you predict and then manage. So you sort of predict the future, and then you manage each step towards that future. Well, the future is more or less unknowable at this point. We can’t really plan more than two or three years out. So what we need is to sense and respond. We need this sort of sensitivity to changes, and an ability to flex and to adapt to meet those changes head on, and always be changing rather than just have fixed organizations that go through occasional, painful top-down reorganizations.

And I think finally another characteristic that I think is really important based on the history of companies, is we need glocalization. We need to be both local local and global.

This is a map of companies, mostly corporations in Southern Germany. And if you look at a map of towns like Gütersloh, where Bertelsmann and Miele are based, or Stuttgart, where Bosch is based, or Munich, where Siemens is based, you will see that these are physically-located companies that actually try and work in a way with local communities, because they need a flow of labor, they need ecosystems, they need suppliers and so on. But if you do the same map for a hedge fund, or a sort of purely virtual financial organization, they really have no location. Maybe it’s on a yacht, maybe it’s off-shore somewhere. And so that means that they’re much more prone to throw negative externalities out there into the community.

And I think these don’t need to be local, physical communities. They can be a virtual networked communities as well. But we need to think about the sort of center of gravity of organizations, and make them grounded in the people that they work with. So if we look at all these wonderful new models that we have to explore, then if we’re going to do this, if we’re going to explore all these models, then I really do think that we need to be conscious of the sort of operating system of the organizations and institutions that are going to pursue that future for us. We can’t just imagine that this belongs to someone else and we can just work on products or startups or these cool new ideas.

We sort of need to get involved in defining the future of institutions, because we don’t want big grand museums like this, which are not very human-scale and don’t change. What we really want is living systems that people can contribute to. And I think those are the kind of institutions that I believe all of you guys with your lovely values can help build, and I would love to see you get involved in. Thank you.