Frank Lantz: Tonight I am extremely excited to welcome Robert Yang. He is the newest member of the full-time faculty here at the NYU Game Center. And that is especially exciting. I have followed Robert’s work, as a game designer and also as a critic and writer, as a scholar and speaker and thinker, and someone who has been teaching game design for many years now both at Parsons and for us here as an adjunct, and has on his blog and on his YouTube series, demonstrated I think some of the keenest and most insightful analysis of games and how they work and how they’re put together, about game aesthetics, and game culture, and game meaning. And also about teaching, about what it means to make games. To wrestle with the creative problems of game design and how they relate to a person’s life. And as an artist and as a creator, Robert’s work has just gotten stronger and more successful. And over the past couple of years, he’s had a series of really remarkable games about gay sex and queer identity, but also about a kind of intervention into game culture about sort of reappropriating the tools and materials and aesthetics of conventional 3D games and channeling them toward something truly idiosyncratic and personal and weird and individual. I think he is one of the talented and smartest people working in video games in 2017. And I am very excited that he is my colleague now, here at the NYY Game Center, and I’m excited to welcome him here to the NYU Lecture Series. So, Robert Yang.

Robert Yang: Hi, I’m Robert. So, first I’d like to thank the artist for this poster. His name’s James Harvey. He’s a really phenomenal artist. Super happy that he was able to draw this poster for me. Also thanks to Charles Pratt for art directing this poster for me.

Okay. So this talk is called “Gay Science.” It’s going to be about thirty, forty minutes long—hopefully more on the side of thirty. And obviously this talk is about video games. So, let’s begin.

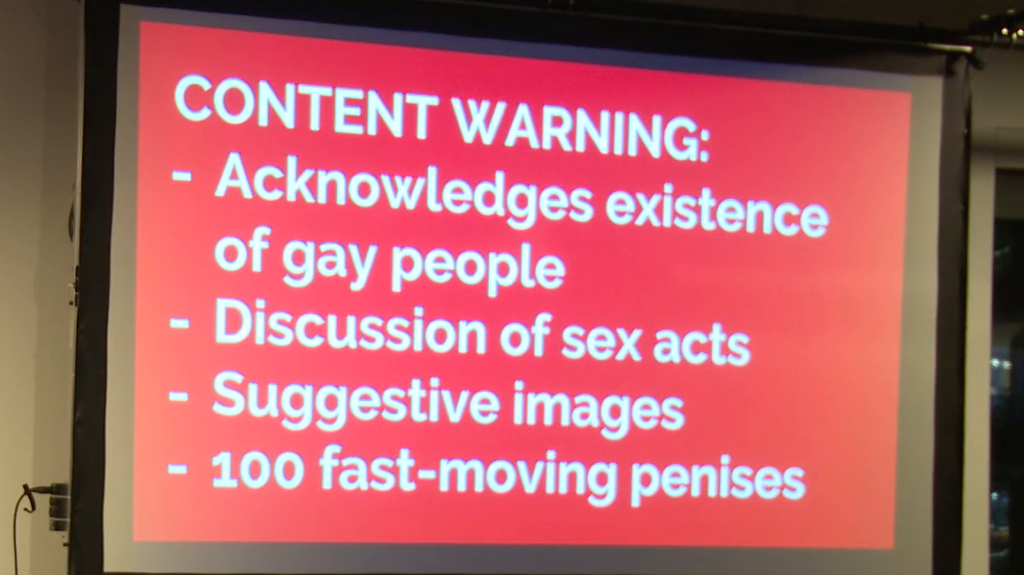

…with a brief content warning. I’m going to be talking about gay culture. I’m also going to be talking about sex at some point in this talk. And there will be suggestive images. And one slide specifically will have literally like a hundred fast-moving penises. And if any of that sounds objectionable to you that’s okay. I’m like half-serious here. Like, feel free to avert your eyes if you can’t take it, or like leave. It’s fine. I’m really okay with it.

So first, Act 1,

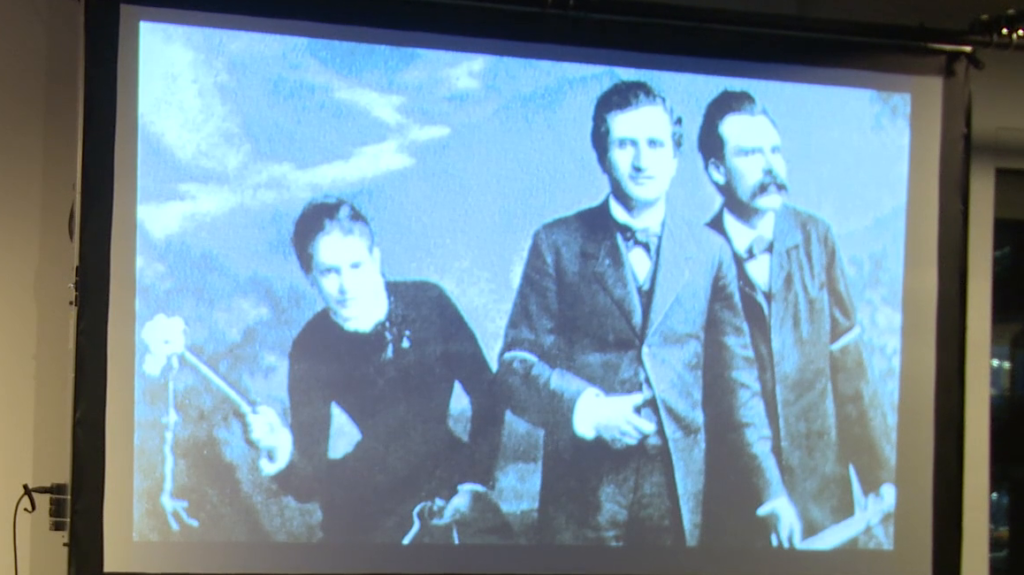

There’s something about Friederich

It is 1882, and Friederich Nietzsche’s migraines are only getting worse. Not only that, but Nietzsche is also vomiting everywhere. When he isn’t vomiting, he also has a lot of diarrhea. And when he doesn’t have a lot of diarrhea he’s also losing his sight. And he’s been sick for so long, for such a long time, that he can’t even remember the last time he was able to sleep. For Nietzsche, life is basically just neverending misery.

Oh. And he also proposed marriage to his best friend’s girlfriend, over there on the left, twice. And he also got rejected, twice. I mean, she’s actually really interesting in her own right. Her name’s Lou Salomé. She was basically kind of a genius in her own time, and became on the first psychoanalysts of her time as well. But she will never feel the same way about Nietzsche, who she sees more as like this mentor and not really as a romantic partner.

So they basically had this big argument, this big fight about everything, and Nietzsche kind of loses both his best friend and her as friends. They kinda have this big falling out. And those are kind of his last few friends in the world, kind of. So he’s also just like a really kind of lonely guy, too.

Why is Nietzsche’s life full of so much pain and suffering? Why doesn’t he have any friends? Maybe he’s kind of an asshole? No, that can’t be, right? So you know, if the problem isn’t with him, the problem has to be like with the world, right? What can he do about it?

Well, that’s when Nietzsche just goes gay—completely, completely gay. And by gay I mean one of Nietzsche’s early books, The Gay Science, first published in 1882, where he basically describes the core of his philosophy. Keep in mind back in 1882 “gay” doesn’t really mean like…gay for the same gender or anything. Gay means more like “a little too happy” or “excessively joyful.” When he says “science” he also means it more in the Shakespearean sense of science. Not just biology or physics, but here science (“science”) refers to any discipline or philosophy focused on seeking truth. So, some translators actually translate this title not as gay science but as “joyful wisdom.” But this talk is called “Gay Science” so ignore those people. They’re wrong. It’s definitely called “Gay Science,” this book and this talk.

And in this book called Gay Science, Nietzsche says a bunch of stuff, including the famous declaration, “God is dead and we have killed him.” But I’m not here to talk about that stuff. I’m here to talk about a sort of thought experiment he proposes in this book as a way for you to kinda test how good your life is. So I encourage you all to take this test with me. It’s kind of called the idea of this like eternal recurrence, or eternal return.

2. “Eternal return”

Nietzsche asks us to imagine, what if some day or night a demon were to steal after you into your loneliest loneliness (“Steal” means like sneak into your room, right, not like steal.) and say to you [Adopts a hoarse voice for the demon’s quotes], “This life as you now live it, and have lived in the past—you will have to live once more, and innumerable times more.” Or maybe he’s like Batman. Maybe the demon’s Batman. “There will be nothing new in it. Every pain, every joy, every thought and sigh will have to return to you.”

And Nietzsche asks, if you had to relive your life over and over and over exactly as you lived it, “would you not throw yourself down and gnash your teeth and curse the demon who spoke thus?” Or curse the Batman who spoke thus? “Or, have you once experienced such a tremendous moment in your life that you would answer, ‘You are a god and never have I heard anything more divine.’ ”

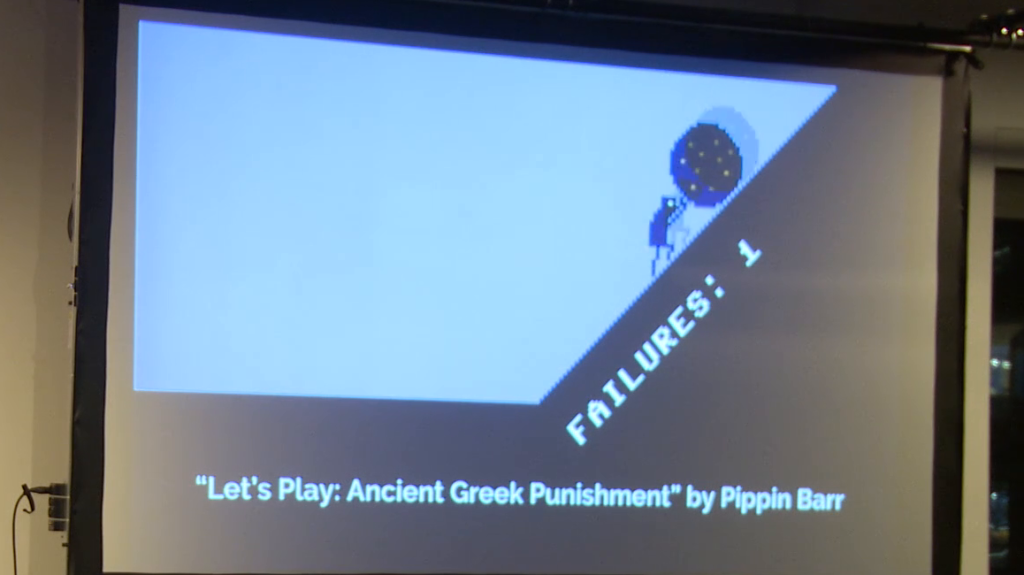

Pippin Barr, Let’s Play: Ancient Greek Punishment

So. If you had to relive the same life over and over, would that be a blessing or a curse? You can recall the myth of Sisyphus, who is forced to push a boulder up a mountain only for the boulder to roll back down each time. Sisyphus was cursed to repeat this pointless task over and over, forever. The gods decided the worst punishment possible was a neverending, very repetitive life of meaningless work.

But the French existentialist Albert Camus famously argued, however, that Sisyphus gets the last laugh here. When Sisyphus learns to accept his punishment, when he’s like pushing up that rock and he’s like, “Man, I really like how this rock feels today,” right, he’s getting the last laugh. Because he’s kind of finding meaning intrinsically in his pain and suffering. Albert Camus argues that “we must imagine Sisyphus happy.” So he learns to love his life, love his fate, and life is worth living even when life just sucks so much.

Or for a more recent point of reference, you can look at the 1993 movie Groundhog Day, where Bill Murray is a cynical, sarcastic asshole TV newscaster guy. And he’s cursed to relive the same day over and over for many years. And spoiler alert, if you haven’t watched this movie— You know, just like close your ears maybe and don’t read my lips, either. At first, Bill Murray’s character lives this really great, hedonistic life where he can do whatever he wants without any consequences, and he thinks it’s just so great.

But as the absurdity of reliving Groundhog Day over, and over, and over slowly drains his life of all meaning, he actually ends up committing suicide…and then wakes up the next day. He can’t even kill himself at this point.

So finally, after ten years of reliving the same day over and over and over— And I actually read in the original script he was meant to relive the same day for ten thousand years. But that was maybe too depressing for American audiences? So they decide to cut that—that’s not Hollywood enough.

But he finally breaks that curse, only when he learns to finally love other people unconditionally. Which is kind of too warm and fuzzy for Nietzsche, actually. If you know a little bit about Nietzsche, you might know that one common critique of Nietzsche is that he’s kind of selfish and narcissistic. And he always kind of pushes people away. He insists that distance between people is really important. And maybe that’s why a lot of teenagers are drawn to him, and teenagers often go through like, Nietzsche phases. But all of us in this room have totally outgrown our Nietzsche phases, I’m sure.

Like if a demon asks you, and just you, “Would you want to relive the same life over and over?” doesn’t that also mean everyone else in your terrible life has to relive your terrible life with you? Like, why’s that your decision to make? Think about your friends, think about your family, who would also be forever cursed to put up with your annoying shit for all of eternity, right? How can you possibly inflict that upon them by taking this thought experiment, right? That would be awful.

But also remember that Nietzsche wants us to imagine laying awake at 3:00 AM in the depths of our loneliest loneliness (his words) disconnected and alienated from everyone else. Does that sound kind of familiar? Sounds a little bit like Nietzsche’s life, right? I kind of feel like when Nietzsche asks whether life is worth living he’s desperately trying to reassure himself, too, right? Like he should stay living as well. And in his own lifetime Nietzsche was actually this walking like indiepocalypse. He only sold a few hundred copies of his books in his lifetime. And he was basically— He died thinking he was kind of ignored, but he was still kinda defiant about it. Was there a way for even Nietzsche to love his terrible failure of a life anyway?

And I’m kind of inspired by this, how Nietzsche’s life sucked so bad he invented his own philosophy to explain why he should survive. It’s as if philosophy isn’t just random stuff that you read for school. Philosophy isn’t just random stuff that Charles Pratt makes you read, right? Philosophy is actually this really deeply personal thing, maybe. A vital tool to help you survive.

3. Toward a gay science of video games

So, now I want to talk about video games a little bit, finally.

But before that a little bit more about Nietzsche. After he died, Nietzsche became one of the most popular philosophers ever. There’s actually been this long tradition of thinkers always appropriate Nietzsche for their own purposes. Anarchists tried to appropriate him. Early Zionists. And famously the Nazis appropriated Nietzsche’s philosophy. Even though Nietzsche would’ve been very anti-Nazi if he was alive during that time. He would have hated antisemitism and he rejected German nationalism, actually.

We can kind of read Nietzsche today, and we do because partly a lot of French left wing thinkers in the 1950s like Foucault, Deleuze, and Derrida worked hard to rehabilitate him and scrub all that fascism off of him. I’d kinda like to join that tradition of stealing Nietzsche’s theories and applying them in a new way. And I also think with the rise of neo-fascism and Nazism today in the world, we may have to defend Nietzsche from the Nazis yet again.

So my way of defending Nietzsche maybe is I kinda want to put the “gay” back into gay science a little bit. And I want to use video games to do it.

Scholars have actually argued over whether Nietzsche was gay or not. Like I read a lot of Wikipedia about this. He wrote a lot about the importance of desire, and passion, and sexuality. But oddly enough he never really wrote about his own sexuality or desire. There’s like a random story about how he wrote a letter to a classmate and told his classmate his lips were kissable. And he basically never married. There’s that one failed romance but he barely showed interest in women. But maybe that’s just because he was a misogynist. I don’t know. It’s really hard to know where he kinda stands on this.

But I think I’m going to stand with one of Nietzsche’s most authoritative, most important translators, Walter Kaufmann, who translated the authoritative version of The Gay Science. And Walter Kaufmann argues in 1974 when he’s translating, that you have to use the word “gay” in translating The Gay Science, because the German word “fröhlich,” that doesn’t just mean like, cheerfulness or joy—or it can’t be, the way Nietzsche uses it. It has to be more than just being happy. It has to be a little bit subversive. It has to be a little bit too happy. It has to be a little bit…gay, right.

And New York City I feel like is arguably getting a little bit less gay every day. I mean if you’re straight you might not really notice it. But a lot of gay and queer people around New York City are kinda always in this weird apocalyptic mood. Like, forty or fifty years ago, New York City was arguably much gayer. Gay bars, gay bathhouses, gay bookstores, gay porn theaters, were everywhere. And now they’re gone, and a lot of these people say, “Oh, New York is like so over,” right.

And for example Times Square specifically. This is a picture from near Times Square in the 80s. Times Square used to be a seedy red light district, home to many marginalized queer people of color. Because they weren’t really allowed to be anywhere else. But then Mayor Giuliani chased them all out and sold everything to Disney. Like literally. Read the Wikipedia on it. And Times Square you know, it used to be somewhere that no “self-respecting” New Yorker would visit. And now it’s still somewhere that no “self-respecting” New Yorker would visit, right. But you have to ask who really benefits from the “new Times Square.”

Also, you might think that Giuliani was kind of on to something. It turned out the best way to destroy and displace gay communities was through capitalism. There used to be more than eighty gay bars across New York City. But after several waves of gentrification, now there may be fifty gay bars. And maybe only four lesbian bars. And actually in San Francisco, there are actually zero lesbian bars there now. San Francisco. This was the last lesbian bar in San Francisco, The Lexington Club, and I think it closed last year.

San Francisco is supposed to be one of the gayest cities in the world, yet the lesbian community there has fewer and fewer spaces. Gay people used to joke that gay bars were like gay church, where they function like these crucial community institutions and you visit every Sunday and so on. And you go there to see your friends. But now these places are vanishing. So I’m also kind of thinking about gay geographies and gay places and how gay culture will survive in the future.

And I promise I’m going to talk about video games soon. Let me just talk about medieval poetry for a second, though. Like, what’s interesting is that this kind of gay history of vanishing and disappearance kind of parallels the medieval sense of the word “gay science.” Back then the term “gay science” referred to lyrical poetry of these people called troubadours, which are like bards or something in the 1100s and 1200s. But in the 1300s, no one was doing that stuff anymore. So they literally started and established all these competitions and academies dedicated to “gay science” to encourage a revival of that form. So it kinda makes me wonder how we can kinda do that now. How can we imagine new gay worlds, or gay academies, or gay science. How does that exist today?

So, video games are supposedly the medium of the 21st century. Video games are supposedly really good at depicting and simulating worlds, and the sensation of inhabiting them. Ian Bogost calls this “transit,” right, this beautiful feeling of being in a place.

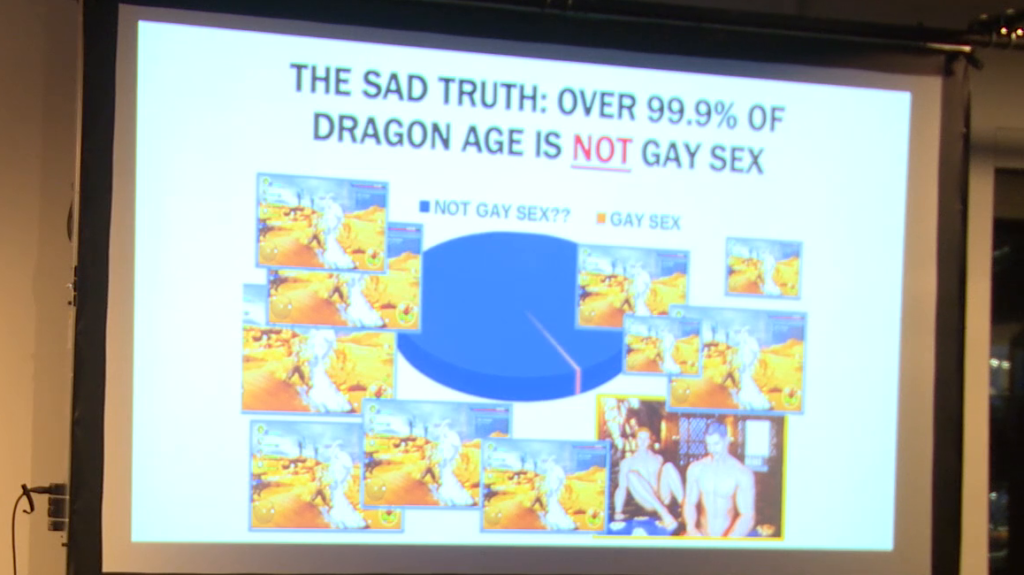

How do we make gay worlds in video games? Well, I can tell you how not to make a gay world. You should not rely on the AAA game industry to pity you and leave you some table scraps. I’m tired of being 0.1% of a world, right. Why isn’t Dragon Age 100% gay sex, right? Get rid of all that boring crafting or whatever. Who needs that, right?

So, I think a better example of gayness in AAA video games is Overwatch, a game where… It’s about like a bunch of random people shooting each other in the future—it’s…whatever. But the developer, Blizzard Entertainment, intended to make one “officially gay character.” And that was going to be their one very generous (Oh, thank you, Blizzard!) gesture towards diversity and inclusivity.

But then, all of Tumblr rose up. And through their sheer force of will… If you Google any Overwatch character names, makes you have Safe Search on, because they were doing lots of gay, kinky shit on Google Image search.

And it’s through this sheer force of will, through this sheer force of their horniness, you know. It warms my heart how Overwatch has been transformed into this game where clearly everyone is gay in this game. And even Blizzard can’t change that now, right. Blizzard just has to like be awkward about it.

And you know, it’s not perfect. But I do think it’s a better example of what I think I’d want from a gay science in some kind of mainstream game culture. It’s not generously bestowed upon us by the grace of the beautiful game industry, right. Instead it is kind of this defiant happiness, this subversive kind of performance of pleasure. Like everyone takes joy in how gay everyone in Overwatch is. And you know, we all just collectively wielded power, and we weren’t happy with .1% of a gay game, or 1% of a gay game. We were only happy with 100% of a gay game, of a gay world, and we took it.

4. Gay science as seduction of the game industry

But why stop at Overwatch? Try to listen to your passion, you know, the desire deep inside you. The gay person deep inside—even straight people sometimes. We seduced Overwatch. Maybe we should just seduce the rest of the game industry as well.

Does anyone know what that means, by the way? To like, seduce something? Like raise your hand if you’ve seduced someone before. Eric Zimmerman, put your hand down. I don’t… Really? Okay, maybe. Maybe, right?

Okay, but seriously. It’s okay if you didn’t raise your hand, because maybe seduction is defined by its ambiguity. Like if you’re too obvious, if you come on too strong, it might be a little bit cute and funny but it’s not like “seductive,” right?

Or maybe you know, she just really likes eating strawberries, right? Like you never really know. Like, “Oh, is that strawberry really good? I guess they’re in season. Oh wait, is she looking at me?” Right? You know, you never really know. Are you reading too much into it?

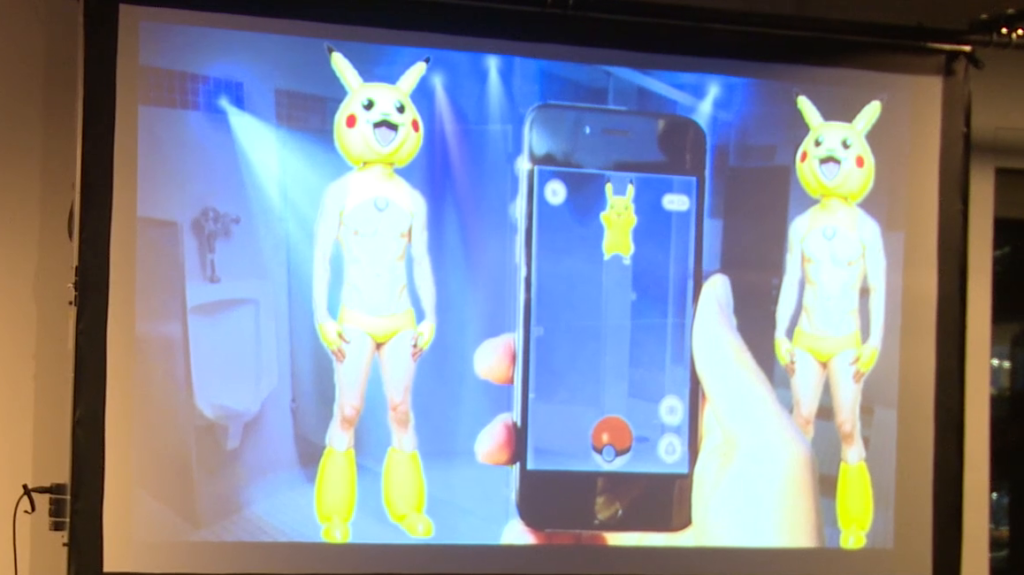

So, I’d like to bring up bathrooms. Is a bathroom seductive in the same way? Well, maybe not by itself, no. But you know, with a little bit of gay science, you can transform a bathroom into what’s called a tearoom, a place for men to anonymously pop in for a quick sexual encounter with another man.

It’s kind of as if this gay world or gay science or gay dimension—whatever you want to call it—it’s kinda like this alternate dimension, or parallel universe that exists in plain sight, maybe. It’s like when two dudes exchange a wink and a nod, and then that consent, that “I see you” kind of thing, that consent transforms the bathroom into a tearoom.

And then if a bystander happens to walk in who doesn’t want to play at all, the tearoom instantaneously collapses back into a regular bathroom, with no one the wiser. And throughout history sometimes like Republican senators have not been very good at this game. And they kinda just mess it up and cause a rip in this gay spacetime continuum, when everyone can see the tearoom for what it is. But most of the time it works. And I think these realities kinda easily coexist without many complaints.

I also think it’s kind of funny how straight people are really excited about augmented reality now because in a sense, gay people invented augmented reality. We project tearooms onto the bathrooms, right. We’ve been playing Pokémon GO for hundreds of years. Why are you so late to the party? We’ve been taking over gyms. We’ve been showing our Pikachus to each other, right? And the real genius of the tearoom is maybe that straight people are kind of building us new ones every day.

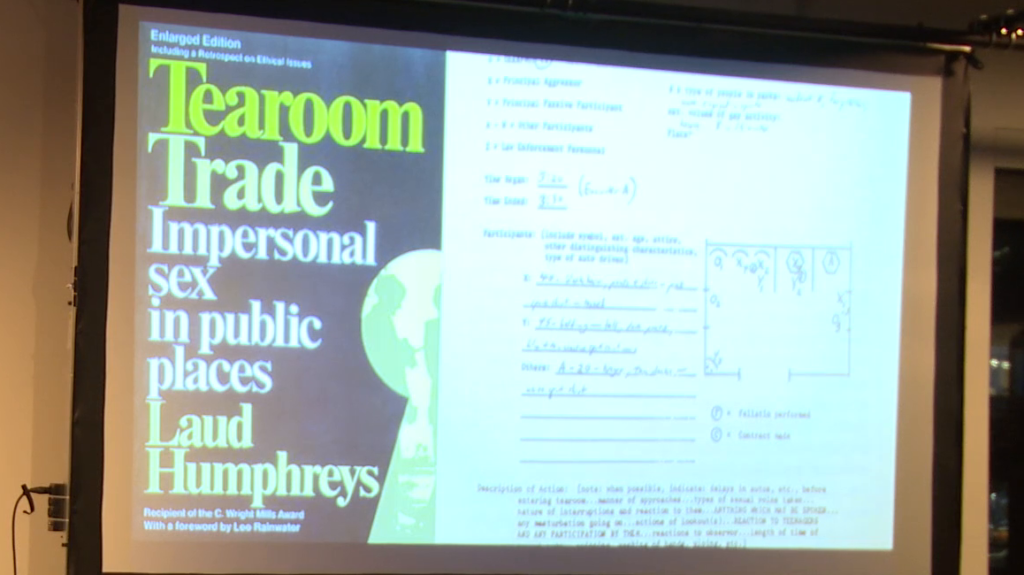

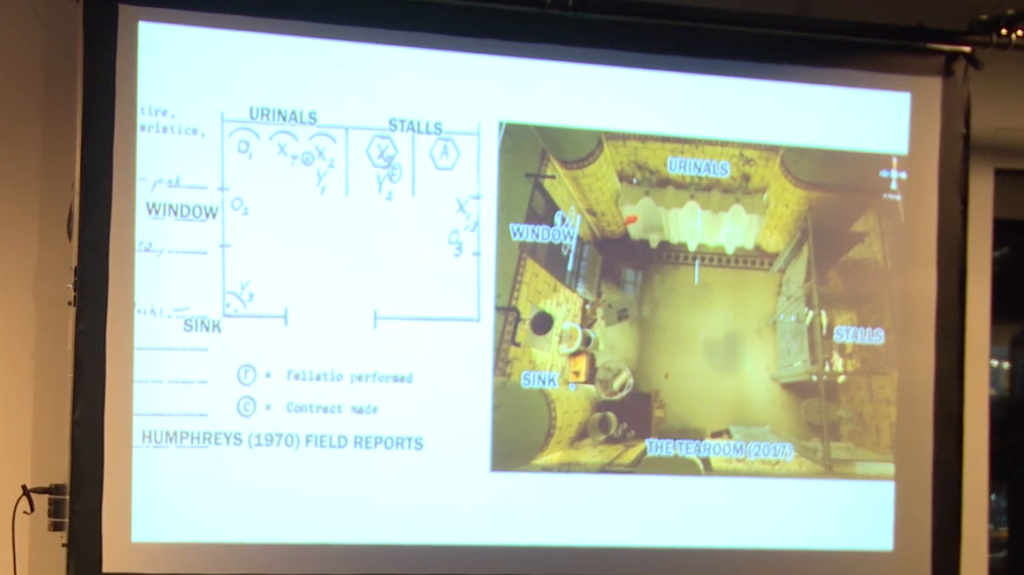

Much of what we know about tearooms is actually from this really famous book called Tearoom Trade. I highly recommend you read it if you’re interested in this stuff. It was published by a sociologist named Laud Humphreys—I’m just going to call him Humphreys. Humphreys visited tearooms, he meticulously took notes about what people did, and controversially he then followed some men home and interviewed them.

But what he found out was that a lot of the men who visited tearooms didn’t identify as gay. Many of them were straight, and they actually lived straight lives. They just liked having sex with men sometimes. So you know, maybe in 2017 they’d identify more as like heteroflexible or bisexual or something. But if you think “gay” as like this umbrella term, this still kinda belongs under this umbrella of “gay culture” because straight culture sure as hell does not want this.

And Humphreys was also really interested in kind of the mechanics of how these spaces work, too, in like the gameplay of this. Like he even uses the word “games” specifically in this book. He talks about players, he talks about strategies. His word for the magic circle was “interaction membrane.” Which sounds really cool to me. That actually sounds cooler than magic circle, I don’t know. And we might define a tearoom not just as this particular place, but it’s also kind of this place in time. It’s also like a system of logic in itself.

https://vimeo.com/255927131

So I actually made a game about this.

[The next several paragraphs, through “…and it’s game over,” are spoken while the game trailer is playing.]

It’s called The Tearoom, and it’s the most advanced historical bathroom simulator in the history of video games. It’s part of my attempt to do gay science to forge new gay geographies in video games.

It’s set in Mansfield, Ohio, which by the way didn’t have a single gay bar from 2004 to 2014, I found out on Wikipedia. And it’s worth noting that tearooms are especially common in more rural areas where there’s not an established gay community or anything.

So in a sense tearooms are kind of logical. People have needs. Tearooms are commonplace. They’re free. They’re nearby. You operate with an expectation of privacy. Why wouldn’t you have sex in a bathroom? It’s a no-brainer, right?

So in this game you hear a car roll up. And you’re looking around. And what I really wanted to focus in this game is kind of your gaze. When you look at this guy, he looks back at you, and he notices you looking at him. And then sometimes you’re supposed to not look at him at all, right. Because that’s how flirting works. I realize most of you don’t know how flirting works. You gotta you know, give and take, give and take. And if he’s not into it, he won’t look at you and he’ll just walk out and it’ll be okay.

By the way you have infinite urine in this game, an industry first.

And when you make enough eye contact with him, the contract is sealed, consent is established… Or maybe not, maybe you have to flush a little bit. I worked really hard on this flushing simulation, by the way.

And then he finally comes over. And notice his penis is a gun. Because the video game police are actually constantly banning my video games. So I thought, I can’t have penises in my game, the only way I can get around this to put in the only thing video games will never ban, which is guns.

And you can see he got caught by this undercover cop, and now that player loses all their progress and it’s game over.

I actually based the layout of this virtual bathroom on Humphreys’ actual drawings from his field reports. And here you can see I kind of try to repeat this same kind of structure. There’s a sink in the lower left. There’s a window the on the left side, there’s a door at the bottom. And really important, there’s three urinals in a row. Unsuspecting bystanders in bathrooms often like that there’s three urinals because that means they can leave the middle urinal unoccupied, therefore maintaining their hetero masculinity or whatever. Because we wouldn’t want to pee too close to each other, right.

But tearoom players also like it because that actually gives them the distance and space and time to negotiate. If you were just peeing next to each other, it would actually be really hard to seal a contractor or do any negotiating of consent there. That ambiguity, that gray space, is really important for seduction.

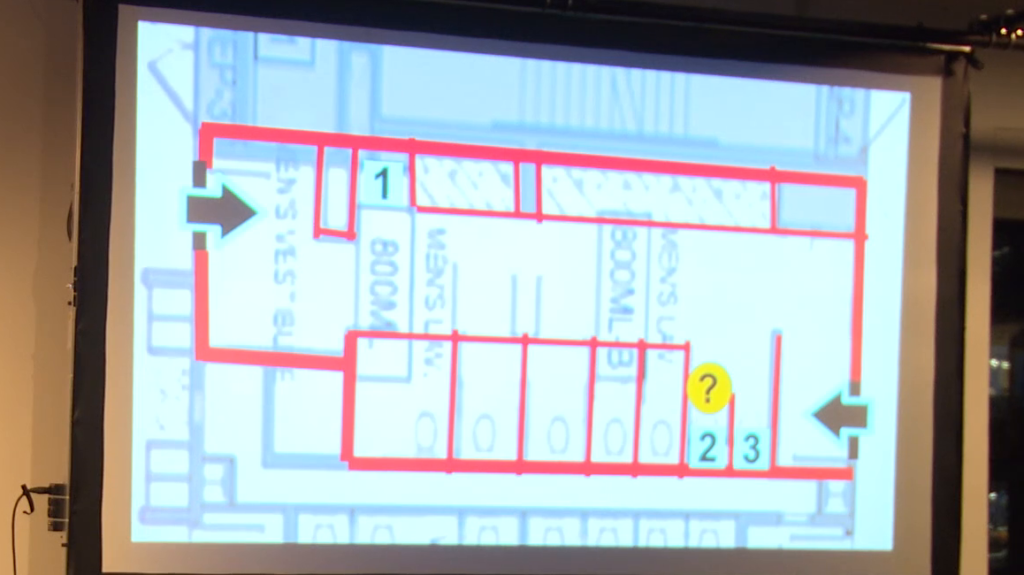

And this is a map of the men’s bathroom actually on this floor, in 2 Metrotech, eighth floor, one minute behind you. This is conversely not a good tearoom. There’s too many entrances. Your line of sight when you enter this bathroom actually sweeps over the entire room with very little warning. Notice that there’s not three urinals in a row. Instead they did this really awkward thing— And visit, by the way, that bathroom and you’ll see what I’m talking about. I numbered the urinals in this map. Number 1 urinal is like next to sink. So someone will be washing their hands, and you’ll be like peeing next to them and you like, share a moment or something. I don’t… It’s just really weird. And then urinals 2 and 3 are down there. But that’s not three, urinals, right. That’s two urinals. So that’s not enough gray area for seduction to take place.

And it’s just really difficult, I think, to find anywhere to have sex in this bathroom. It’s a really bad design flaw. Frank, where were you on this? I feel like the one place you could maybe have sex in this bathroom is maybe that orange spot right there. Because at least you’re shielded from that left exit, and maybe in the right exit if you hear someone opening the door fast enough you can zip up or something. I don’t know. It’s just not a very good bathroom.

And I feel like that’s not a coincidence, that this bathroom is both bad for sex and just both bad in general. Like it’s just unpleasant to be in there. And if you visit it after this talk you’ll see what I mean, I think. To have sex in this bathroom I think would be to bless it. And I refuse to bless this bathroom. I can’t wait to move into the new building and see that bathroom.

Image: Mitch Alexander, terracedcottages

But some bathrooms are actually really great for cruising. It’s as if they were tailor-made for cruising. They’re super evocative. Like if you look at this photo, there’s this photograph by an artist name Mitch Alexander as part of this project to document an “aesthetic of tearooms.” Or cottages, as they’re called in the UK. And I feel like if I visited this bathroom in real life, I would be just totally clueless, right. I would not have noticed anything.

But when Mitch photographs it like this, and it’s just a little bit dark on the left side and there’s something around the corner— Hm, I wonder if there’s gay sex around that corner, right? It’s suddenly become so much more mysterious and evocative and seductive, even. It’s like I’ve tuned myself into this new frequency suddenly, where I’m noticing new things that I never noticed before. And I think when we notice these new aspects of our world, we can create new worlds within that.

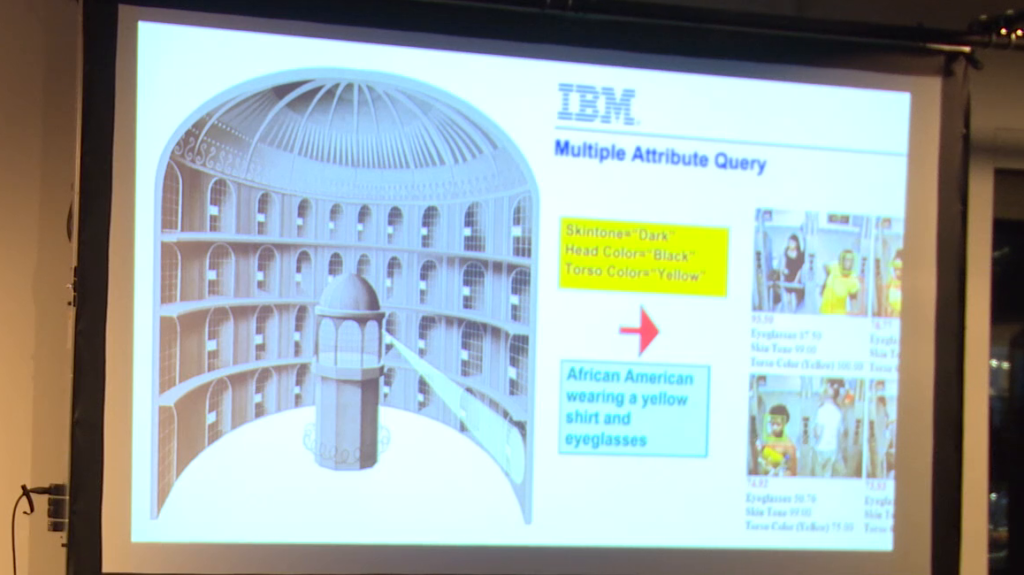

But you also kinda just need to think beyond physical architecture. Over here on the left is the Panopticon. Are people familiar with the Panopticon? It’s kind of this theoretical philosophical prison, or dream prison I guess, where prisoners never really know when they’re being watched and thus they always regulate their behavior. That was the whole idea of it. But actually the idea of a panopticon is totally obsolete. You know, you don’t really need to build prisons if you can already put cameras and surveillance everywhere, and you can make the entire world into a prison anyway.

So over there on the right you can see some beautiful surveillance software being designed by the fine folks at IBM, which I’m sure will be sold to every friendly government around the world.

Once you recognize the system of control you can begin subverting it. Walls and windows are just metaphors. When I talk about level design and architecture and stuff, I want to try to apply that same logic and analysis to the structure of society itself and have the metaphorical equivalent of gay sex in the structure of society itself. Whatever that would be I don’t even know.

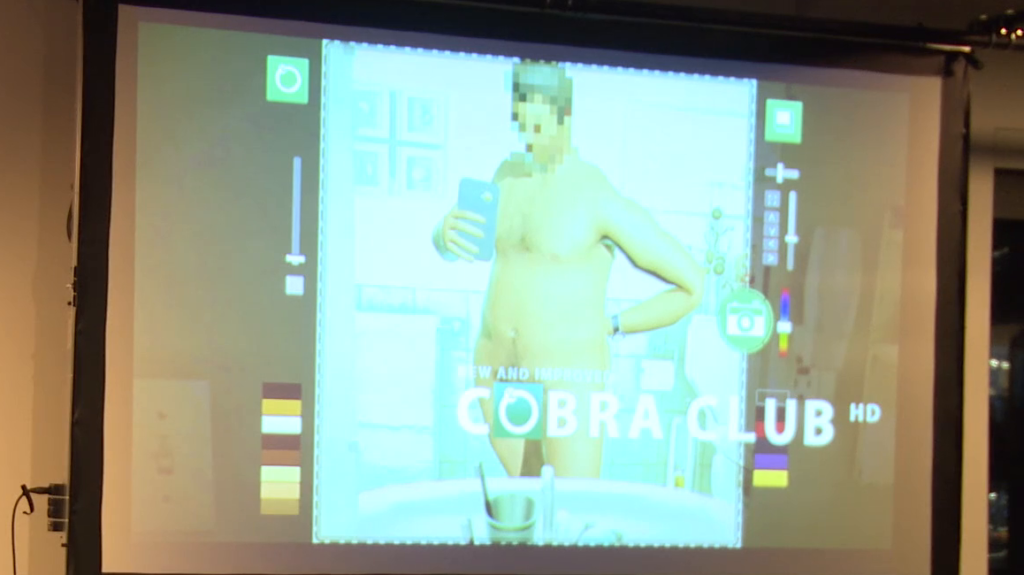

So a while ago I made a game called Cobra Club. It’s a dick pic photo studio game, where you’re in a bathroom. And I guess I really like bathrooms. I’ve made multiple games about bathrooms. And in this game you kind of play with all these different sliders, and play with all these Instagram filters and make your own fun little dick pics. And I think you can totally locate some of the art of this game within the first-hand experience of playing this game. But to me a lot of the art and meaning of this game also has nothing to do with really playing the game. A lot of the art and meaning of this game has to do with how the game actually secretly leaks all your dick pics that you make in this game to a public database without your knowledge or consent.

And then this is what it looks like. And then the game is like, “By the way, I’ve been stealing all your dick pics and I’m sending them to the NSA. Hi.” And it looks like this. This is how surveillance and systems of control work. Once you know that complete strangers or government officials might be looking at your dick pic, you’ll probably making them a little bit nicer at least, right? Put a little bit more time into them.

To this day, the Cobra Club database now has over 75,000 dick pics. That is 75,000 more dick pics that me and thousands of players have lovingly brought into this world and uploaded to the Internet. And there’s still more every day. And thanks to our monumental efforts I’d like to think there’s at least .001% more pornography on the Internet. Thank you. Thank you all.

So, when I make my sex games I kind of want them to extend outside that magic circle, go through—penetrate that interaction membrane, if you will—and touch this larger system that kind of surrounds us all and informs our lives. Because I think that’s where sex and seduction go, you know. Like oh, are they interested in me? Every relationship has to have that talk where you’re like, “So what are we?” right? Like you need to eliminate the ambiguity in the relationship in order for seduction to end and for you to go on with your life.

5. Eternal games as seduction

So, I kind of want to end this talk with the idea of an eternal game. So if you remember that whole thing about the eternal return and eternal recurrence, that thought experiment about reliving the same life over and over. As game designers, we get to live in our own special hell when we take that test, right. If you’re reliving the same life as a game designer, that means you’re remaking the same games over and over and over. So I guess this is also kind of about what game would you gladly remake over and over and over?

I’ve actually been doing this a lot lately. I’m kind of obsessed with this idea of remakes and remasters. I’m currently in the middle of the third remaster of my game Radiator 2. And I’m just enjoying it so much I think I’m just going to keep remastering it, like forever. I think every year or two, I’ll just update it and change the graphics up a little bit. What if you remastered a game five times, or a hundred times, right? Or a thousand, a million times, right? How would that change the meaning of your game and its significance to your life?

But if you’re going to take such a long view of things, such an eternal view of things, I think you also have to think bigger than that. Like my games I think aren’t just about taking dick pics in bathrooms, or having sex in bathrooms. If you zoom out a little bit more, I think my games represent one bathroom in an ocean of many other bathrooms. It’s all virtual. All the walls, all the windows, are metaphors. The bathroom is a metaphor, right.

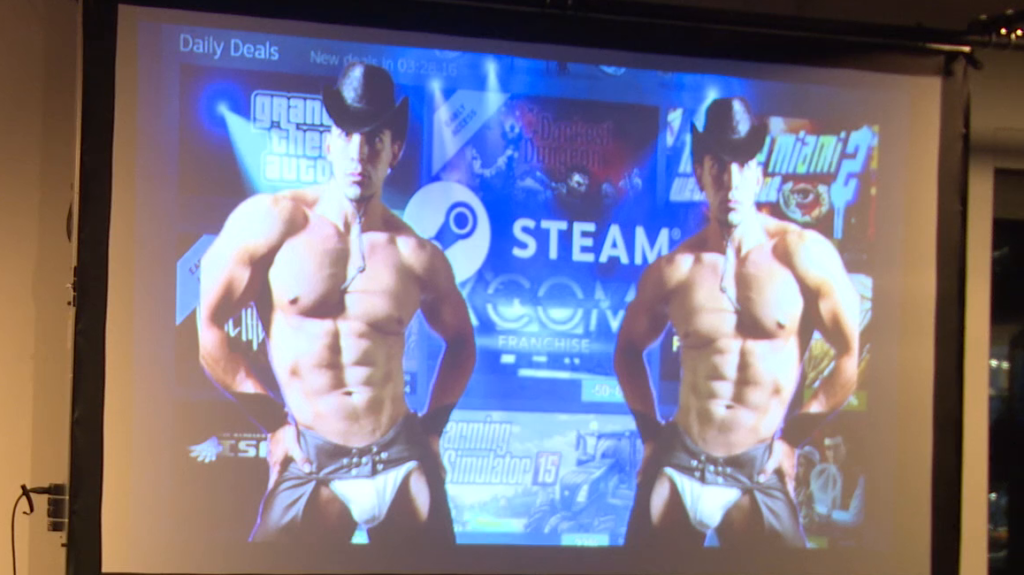

Instead, I want to not just cruise for sex in a bathroom. I want to cruise for sex in the entire video game industry. Let’s have gay sex in the Steam dashboard, right. What would that look like?

So I think gay science is about kind of finding these margins of the game industry. And then you fill that up with gay sex until it envelops the game industry completely, just like Overwatch or something. So despite all our pain and suffering you know, we have to keep living, we have to keep surviving, we have to keep creating, we have to keep worlding new worlds. We have to find every hidden alcove, every secluded orifice of the video game industry and do all kinds of gay shit in it. To me this is poetry. To me this is gay science.

So why stop at cruising just in my games, right? Like, the next time you’re driving around in Mario Kart you know, maybe on like Rainbow Road or something, take a pit stop with your friends and honk off each other. Why not? Or you know, the next time you boot up PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds, run over to the bunker and hide in the corner, and then tap your shoes twice and listen for someone to respond. And you might be in for a pleasant surprise, right?

I don’t want just one video game about having gay sex in bathrooms because really, I think all video games can be about having gay sex in bathrooms. The entire Steam catalog can be your bathroom. And it often is, right?

And when you do this, I’d really like it if you just let me know. Because I’d really love to hear all about it. First, I will listen attentively to you. To every nasty, sordid, juicy little detail you have to offer. And then with due reverence, I will lean over to you and whisper, “You are a god. And never have I heard anything more divine.” Thank you.

Frank Lantz: That was beautiful.

Robert Yang: Oh, thank you.

Lantz: And we’re going to open it up to questions from the audience. But first I get to ask a few questions. That’s my prerogative. And I’m going to start by asking… I’m going to shift gears a little bit. Like in Stick Shift. And…

Yang: I got it.

Lantz: Thank you. And ask a little bit about your process as a creator. You started out… Like there’s a thing when you showed that scene from The Tearoom, it is a first-person game. And that’s a big part of what makes that game work I think, right, is that experiential kind of like…that being inside of this space and being…really embodied in the experience of it.

Yang: Mm hm.

Lantz: And you started out modding 3D games. It’s always been an important part— Like, I guess my question is how important is that first-person perspective to you? You started out making basically Source engine mods, modding Half Life. And you’re now working in Unity I think, primarily, is that right? [Yang nods] And you know, how key is that to your ideas and your work, that first-person-perspective?

Yang: I think it’s really key because for some reason I think just the first-person perspective brings this weird like, immediacy to it. Like you’re there, and if you duck behind a wall, you now can’t see anything because you ducked behind a wall, right. So I feel like when you are first playing in a first-person game, suddenly your place in the world matters so much more, and you’re so much more aware of how you fit into the world.

So I think that’s why— Or at least that’s like the nice, beautiful, poetic answer maybe I’d offer to that. Really I think I also just really liked violence for a long time—

Lantz: Really.

Yang: —and I really liked shooting people in the face. But then, I realized we should shoot people in the face in a totally different way, right. And then I felt like violence is kind of this trope that we lean on way too hard in video games. It’s important to explore violence and think about violence. But to lean on that as the default crutch or interaction, it’s just kind of lazy I think. And then I thought what’s the only force that’s nasty enough to repel violence in video games? And gay sex was that answer.

Lantz: Is there… Has there… Do you miss those Source engine days? I mean there’s a certain quality to the look and feel of Half Life and games that were built on that engine. And Unity has its own kind of aesthetic overall look. Do you miss those days? Do you miss making Half Life stuff?

Yang: Um… No, I mean I like having money now, so it’s okay. But…

Lantz: How do you make money? Do you charge money for your games?

Yang: No. They’re actually [crosstalk]

Lantz: Where’s the money coming from?

Yang: Oh. I think you.

Lantz: Oh.

Yang: I think you, actually.

Lantz: Yes.

Yang: I think.

Lantz: I did— Yes, I pay you to teach.

Yang: Yes.

Lantz: But I would have done that if you would have continued making Source engine mods.

Yang: Right.

Lantz: I guess… No, I guess not. I guess yeah. Your ability, like your… I guess it’s true. I see the connection. I see how it all adds up.

So is that it? You just followed the money? You just like, “Oh, this is what the world wants, is Unity.”

Yang: That’s why we all get into video games, right? To be really rich, right? Now, I think I do miss those days a little bit. Because that was when I easily fit in with straight people a lot. And now, when I started making all this gay sex stuff, now people are like, “Oh yeah, you’re that promising level designer that suddenly went off the rails and made all this gay sex stuff. How are you?” And then it’s like oh hey, I’m fine. How’s your mother?, right. So it’s kind of like, I think I miss that kinda more for the community a little bit. Like a sense that we were all kinda speaking this similar language, and kind of working with the same tiny problems that no one else cares about but are really important to us for some reason. And that kind of fellowship was really helpful in my growth as a developer, I think.

Lantz: Your games get streamed a lot on YouTube.

Yang: Right.

Lantz: And I think my understanding is that you have a bit of a contentious, or ambiguous relationship to streamers, right. In some ways, I mean you appreciate the exposure. (We know you like being exposed.) But on the other hand, you… Is it hot in here? On the other hand I think you…from what I’ve heard you talk about you’re not crazy about the way that your work is framed often, as just like sort of… You know, first of all it’s sort of free content for for people who are just exploiting it for that purpose. But then also kind of treated as a parody or a joke when it’s not intended always like that. I don’t know, what are your thoughts on the people who stream your work?

Yang: Yeah, so my relationship with YouTube is kind of weird, because a lot of YouTubers like playing my games, and I like it when other people enjoy playing my games. But you know, as any game developer can tell you, when you make a game and someone else plays it, they might not play it the way you think they should play it, right. So I make games that in my mind celebrate gay culture and queer theory and all this stuff. But in the hands of a homophobic YouTuber who’s like a shock jockey who wants to deal in scandal and stuff, they play my games and weaponize them into weapons of homophobia and stuff.

I actually try really hard not to watch YouTubers play my game, because it’s really upsetting to me sometimes how I feel like I’m complicit in them broadcasting homophobic messages to their audience. It kind of becomes this way for them to point to gay sex and it becomes this two minutes hate thing for them where they can spit and growl at it and laugh at how disgusting it is. When really the joke was more “Isn’t sex and bodies weird? Isn’t it fun how sex can be like this or like this?” That was kinda more when I was going for, but unfortunately video games have players. I look forward to the day when video games do not need players at all. When I can just have an AI just play my game and no humans are involved.

Lantz: Okay, let me see if I can make an argument—

Yang: Unless it’s homophobic AI, that would be bad.

Lantz: Let me see if I can—

Yang: Facebook’s making it right now.

Lantz: I’m going to muster a defense for this hypothetical streamer that you’re describing, whose growling and spitting. Maybe this person is like…as hateful as it is, maybe this is the way that this person has gay sex, right. You know what I’m saying? Like you know, they would not be playing your game and streaming it if there weren’t something there that they were drawn to, right? They’re not ignoring it, right. They’re playing it and they’re playing it in public, right. And this public performance of growling and spitting, is their response. You know what I’m saying? Like that is in and of itself pretty gay, isn’t it?

No?

Yang: Do you— Have you like, met gay people? I just feel like if I want someone to growl and hiss at me for who I am, I’ll just like walk outside or something, right. I don’t know. I want more of a substantial reaction from a YouTuber. If they are going to do that, they should be really smart about their homophobia or something, right?—No, I wouldn’t want that either.

Lantz: Yeah. I don’t know. Here’s how I’m getting to this place. There’s a sense— I’m trying to figure this— There’s an interesting puzzle at the heart of your talk and your work, and the more I think about it the more confusing—the more dizzy I get. Which is that there’s this relationship to video games… Like you were talking about how there are fewer and fewer lesbian bars in San Francisco. Which is…weird, right?

Yang: Zero. Zero.

Lantz: But it’s not because there are less lesbian people, I don’t think. Or it’s not because lesbian culture is less accepted. Maybe it’s partly because gay and lesbian and queer culture is more accepted, right. It’s more mainstream. There’s less of a sense in which there needs to be an explicit kind of separate culture, because it is more and more mainstream and it’s more and more accepted and it’s more and more understood as being part of the spectrum of human life and culture and no longer this forbidden, underground thing. And so in some ways it’s what success looks like, right. In some ways it’s a good thing. But in some ways it’s… As you pointed out, there’s a tragic loss to it as well.

And I sometimes think about that in terms of video games in general. Sometimes I think about what video games used to be before there was even a hint of respectability. When it was just…they were considered gutter culture, you know. As something that it was obvious on the surface of it that they were for children and degenerates, for pre-adolescent, twisted male psyches. That there was nothing serious or important or culturally significant about them…

Yang: You run a games program, though. You know that, right?

Lantz: Yeah. But do you remember when games had this status? It’s true, right? And that’s less and less the case, right? More and more, I think there was a sense in which people who got into video games, who saw something more to them, recognized that they had the capacity to be rich and expressive meaningful culture in the same way that music and film and these other things could be. And were excited about the idea that they could rise in their status and be accepted alongside these other cultural forms.

But, as that happens, in the same way that one might miss the quality of being marginal, right, for its character, for its power, there is a sense in which sometimes I worry about that for video games in general. And I don’t know if I’m over interpreting what you’re saying, but there is a sense in which video games were always queer culture in that sense, right. In the sense that they were marginal, they were not considered mainstream, that they were considered the other, they were something for people who were not normal, who were not accepted, who were not… You know what I mean?

And…I don’t know, is that… Does that fit into that picture the that you’re painting of the gay science of video games? The fact that they were maybe always gay? Because in your work, you’re pointing out the way which video games are the mainstream. But if you step back a little bit, in the same way that you’re pulling back the camera to see the bigger picture, there’s a sense in which video games were always already gay.

Yang: I don’t think that’s what I’m saying.

I mean, maybe I’ve confused myself. Maybe I didn’t have a point to begin with.

Lantz: Yeah. But do you see what I mean?

Yang: Yeah. I think you’re wrong, I think.

Lantz: Really? So if video games were straight…

Yang: Okay okay, let me—

Lantz: Back when they were like—

Yang: Let me start like five minutes ago.

Lantz: Okay.

Yang: Like, I think… You were talking about lesbian bars, right.

Lantz: Yeah.

Yang: And the issue of disappearing lesbian bars… There’s a lot of debate about why exactly they’re disappearing. Is it disappearing because we don’t need lesbian bars anymore? Well, talk to lesbians and they’ll disagree with that—they want lesbian bars. So why are they disappearing? Is it because rent is going up really high in San Francisco? Is it because women are paid less than men on average, so they have less money to rent and go to bars and spend money in disposable income and stuff? So—

Lantz: But that was also the case back when they were thriving.

Yang: I mean, it was cheaper, though, I think. I think it was a very different climate back then. So, to that extent I think it’s really weird to argue that video games were always gay, because I think a lot of gay people would be like, “No, they didn’t feel that way then. And they still don’t really feel that way now,” as I’ve argued.

Lantz: I mean yeah, maybe I’m pushing too hard to make this move. But I think it’s similar to the move you made at the very end when you talked about how in a way, sex is gay, right. Like not just gay sex is gay, but like…

Yang: Okay, I’ll take it.

Lantz: Right? You know what I’m saying? Like there’s something queer about sex, right?

Yang: Okay, yeah.

Lantz: When you think of the role sex occupies in culture, it is this thing on the margins. It’s this thing that’s hidden. It has a weird transgressive power. It’s not part of our normal daily experience. And yet it is…it is normal. It is natural. It is powerful and it’s beautiful. Um… Uh. Yeah. Right? So that’s kind of what you’re saying? Have I got that part right?

Yang: Let’s just say yeah.

Lantz: Okay.

Yang: I think.

Lantz: That’s the sense in which I think of… My interpretation of your message is that video games are the gay science, right? That that’s…right?

Yang: Well, maybe not yet. [crosstalk] Not yet.

Lantz: They could be.

Yang: But they could be. I think that’s kind of what I’m saying.

Lantz: But they…but they can’t be, Robert, don’t you see. Because if… [Yang and audience laughing] Hear me out. Hear me out. Because if they were, right, if they were, there would still be a need for… There’s always a need for the other, right. The power of that perspective, of the queer perspective, is not in the particular identity, right. But it is in the… There is always a perspective which is outside of the frame of what is considered normal and accepted. So if you were successful at transforming the video game industry and making it fully gay from top to bottom in this way that you’re picturing, wouldn’t just make it straight? Like wouldn’t that— Do you see what I’m saying? Wouldn’t that make…

Yang: Always want to bring it back to straight people.

Lantz: Well, I mean. Do you see what I’m saying?

Yang: So I feel like… Don’t take it super literally, right. Like when I say Overwatch is completely gay… No, of course not, right. It’s actually built and owned by 300 straight dudes living in Southern California, right. That’s what Overwatch kind of is as well. So when we articulate a demand that everyone in Overwatch is gay, or replace every game on Steam with gay sex, right. When you do that, that’s articulating more like this radical agenda that may never be fulfilled—

Lantz: Right.

Yang: It’s not supposed to be a practical agenda.

Lantz: Right.

Yang: It’s supposed to be a queer agenda—

Lantz: Right.

Yang: —where it’s just supposed to get people upset and angry and change things.

Lantz: Right.

Yang: I think. At least that’s my view.

Lantz: Yeah. This is how I’m interpreting what you’re saying. Like, Nietzsche’s larger point is that you cannot construct values within in a value system, right. If you’re inside of Christianity, you cannot then really understand— You can’t construct a morality withinside a morality. And yet we’re all in this position of having to construct morality for ourselves and each other, right. We have to come up with values for how to live our lives, and beliefs and behaviors, ways of living, that we believe are correct and true. You can’t do that if you’re already inside of one of those systems, right.

Yang: Well, we killed God.

Lantz: Right. Killing God was the escape.

Yang: Let’s get rid of all the other stuff, too.

Lantz: Yes. Yes. And, yeah. And so I guess… Yeah, I guess this is an endless process, right. Does it end somewhere? It doesn’t end when oh, this is fine, now we have the correct amount of gayness in video games or in the world, but rather it’s just this ongoing process of always being able to escape from the existing framework of what is considered normal, standard, accepted. And in order to discover what is possible, what is true for us, now, at this given moment versus what is imposed on us as being normal or…

Yang: Yeah, there’ll never be this moment where everybody’ll be like, “Okay, gay rights won! Let’s all go home now,” right. I mean, that’s what some people want to happen, and that kinda sucks right now. But it is this idea that like, we’re always heading toward some horizon, toward some rainbow over there. And we’ll never reach it, but it is important that we keep going towards there, right.

And I think that plays into this idea of like eternal return, right. The struggle isn’t going to end. Your life will be full of pain and suffering, forever. But it’ll also be full of art, and beauty, and things to distract you from pain and suffering temporarily. And that’s what makes kind of life worth living in the end, right.

Lantz: And I do realize that what I’m doing is maybe a little bit in danger of being an appropriation—an attempt to appropriate, like the sort of straight— Because I want… You know what I mean? I to claim some…

Yang: You want to be gay.

Lantz: I want to be gay, is what I’m saying. [audience laughs] What I want is to claim for like, queer— You know this idea of like…the power of queerness, to have nothing to do with sexual preference, right. To say it’s not about what genitals you have or which genitals you like to rub up against. But is rather a desire to look beyond what is imposed on you as normal or accepted or standard, and to be seeking, always, other possibilities in order to create for yourself these values. And to say that yes, we can do that regardless of our sexual preference.

Then I realize yeah, that’s a weird move. Because you know, as a supposedly straight dude, to be wanting to be able to claim that maybe I should just be like oh yeah, that’s fine. I don’t need to own that too, you know what I mean? So… Let me ask a couple more questions, [audience laughs] and then we’ll put it up to the audience.

[Checking notes:] All sex is queer sex, yes we covered that.

I’m going to say…one more question, which is you wrote recently a very funny and insightful piece about how you don’t always need to play video games in order to understand them and interpret them. And one of the things I liked about this was that in some ways it’s the opposite of what video game intellectuals have often said, which is like, “You’ll never understand video games if you’re just watching them over the shoulder of a player,” like they’re essentially about interactivity. Until you understand what it means to be inside of a video game making choices and taking actions and experiencing that, then you’re just looking at it as a cartoon.

But then you made this point and it’s like I realized oh yeah, it’s really true. Especially now. So to what degree do you think people need to play your games in order to understand them? Can I watch a video of you game and get most of it, or do you think people really do need to play them?

Yang: Yeah, this is one reason why I always put out artist statements with my games. Because it’s actually really great if you don’t play my games. And it’s great if you don’t watch them, either, because that means PewDiePie gets less ad revenue, right.

So again, I think games are beyond just this commodity or product you consume. There’s culture that we’re swimming in all the time. And when you consume a game there’s so many different ways to consume a game, right. You can watch someone else play it. You can talk about it. You can talk to someone else about and lie about having played it. Which is what I do all the time, right? Like, I think that’s kind of the common sense every day relationship we have with games. And I just feel like we should be more honest about it?

Like if I’m playing Call of Duty, and my mom is watching me play Call of Duty and she’s like…“That looks stupid.” Does she understand Call of Duty? I would argue yeah, maybe she does, right? How can you argue she doesn’t, right?

We put such a focus on depth and stuff in gameplay, and that’s certainly important. But I think there’s also another dimension of like cultural depth that video games are still in baby aesthetics land, and we still haven’t figured out how not to be embarrassing.

Lantz: It does seem like one of the things that’s happened in video games is that in the past couple of years video games have gone through some of the same stuff that happened in film like during the 70s, right. This awareness of the influence of videology on formal qualities and aesthetics qualities, of how film works as culture. And the importance of identity and how identity is expressed through film, stuff like that. And sort of video games just recently went through a similar set of realizations all of a sudden. But it was like an atom bomb had gone off at Toys R Us, you know what I mean? Things like—

Yang: Toys R Us doesn’t exist anymore. Do you know they went bankrupt?

Lantz: Because of the atom bomb.

Yang: The video game atom bomb, okay.

Lantz: And you know, we saw this incredible, weird, reactionary backlash. You had Gamergate, and there was this… It was as if people had just never…had never like, left their bedroom, right. They’d never recognize that in the past fifty, sixty, a hundred years, what was happening in culture. How worried should we be about that that? Is that a normal thing? Is that just a process that culture goes through? Or is there something special about video games that caused them to have this reaction?

Yang: So, I think this kinda reminds me of what you were saying earlier when you wished you could detach gay and queer identify from sexuality and gender and all that stuff. Because if you’re going to argue that games were always queer because misfits, all misfits are queer, then you also have to include Gamergate, who are misfits in that queer umbrella. Which is really disturbing to people already under the queer umbrella. They’re like, “No, don’t come under this umbrella…”

Lantz: That’s what the video game folks said. That’s what the video game folks said.

Yang: You’re going to slash this umbrella to pieces. Please don’t do this.

Lantz: That’s what they said, Robert, right?

Yang: Okay… But we’re gonna like die from it. Or we get death threats over it and stuff, too. Right? Like it kind of takes… I don’t know how much you’ve been harassed on the Internet. I’m sure you’ve seen your share. But when you get hate mail or like Nazi death threats on Steam or something, it kinda sucks. And then you’re like… Okay, you are not my queer ally misfit fellow gamer, you’re this weird hostile force that’s trying to destroy me.

So my reaction to a lot of that is to kind of… I think that’s why I don’t trust players anymore. That’s why I wish people wouldn’t play my games anymore. Like, I think in the end I kinda had to draw a lot of boundaries and pull myself back from that, or else I would get destroyed I think by that, if I let video games consume so much of my identity and had so much of that depend on video games.

Lantz: Yeah. Wow. Alright, let’s open it up to the audience, shall we? Are there questions out there? Yes.

Audience 1: Is there any other people that are kinda like disrupting or subverting those kind of social or cultural norms through video games that you would like the highlight? Other people that—either your colleagues or just people that you look up to or that you like their work?

Yang: Yeah. I really love Christine Love. If you’re not familiar with Christine Love’s work, she makes grand like, Korean sci-fi space opera like murder dramas that are just really, really intense. And then they’re also very much about intimacy between women.

Some people ask me why I don’t put women in my games, and sometimes those people are like straight men who wanna like honk off to my games about having sex with straight women. But I don’t do that because I think people who are immersed in that identity are already doing it, and I’d rather highlight them than try to mime or perform as them a little bit. So, Christine Love’s really great.

I really like Kitty Horrorshow, if you know Kitty Horrorshow. I’m actually commissioning her for No Quarter. Come out in a month, November 3. But Kitty Horrowshow, she does really great games that play with like the materiality of it. She’s making these really creepy horror games about like capitalism destroying us and these hollowed out cathedrals. And then it looks like in 90s CG or PlayStation 1 games, almost, in this really deliberate but like haunting and affecting way. And I feel like that’s pushing a lot of boundaries as to video game aesthetics. Like how should games look and operate? I’m always impressed by her work a lot, too.

Lantz: Yes.

Audience 2: I’m just curious if you’re willing to share what inspired you to go from as you said, promising level designer, to the person who makes—

Yang: Why did I throw my life away? Oh my God. I ask myself that every day. Well, what really happened was I graduated with a degree in English, which is super useful. And then I decided well, maybe I’ll just— Because I was modding a lot at the time, making all these levels. So I thought maybe I’ll just go join the video game industry and make some murder simulators or something.

So then I went to GDC and I got an interview with Valve somehow. And Valve back then made games and stuff. They were great. And back then I sat down with Valve and I showed them my weird gay divorce simulator mod. And then Robin Walker totally played it and went through it and was like, “Oh yeah, okay. This is really smart, really well-designed stuff. But it’s kind of too weird. Like, if you were to work on Half Life 3, we don’t know where gay divorce fits into Half Life 3.”

And I was like, “Oh really?”

But he was like, “Really.”

And then I was basically kinda told I was a little bit too weird to fit in the industry. So he was like, “Why don’t you make some normal levels where you like shoot monsters and stuff?”

So I was kind of faced with this choice, right. I could either go in the game industry and make normal stuff, or I could go to art school in New York City and just be even more gay or something, right? And that’s what I chose, and here I am now.

Lantz: Yay!

Yang: Don’t follow my footsteps. I don’t— No, don’t do what I did. Take the job at Valve. You do it.

Audience 3: I was really happy to hear you talk about flirtation and seduction. I think anybody who’s played with your library can see those mechanics kinda getting more and more integrated, more and more complex. And obviously more and more fun. And I think most video games, those mechanics are either circumstantial or inadvertent. Also very fun. I’m wondering how moving forward you plan on developing those kind of mechanics. And in a fantasy world, where would you take that?

Yang: Oh God. I think a lot of my approach to making intimacy or like flirting in games came from that slide about Dragon Age, where I noticed like, Dragon Age is known for gay sex, and they spend like five seconds on gay sex. So if I just spend ten seconds on gay sex that’s already two times better than Dragon Age, right?

So I was thinking like, well I can just keep making these short games. All my games are pretty short to play, by the way. So even if it’s just two minutes, that’s already…like, a lot can happen in those two minutes. So in terms of how to do intimacy in that, and seduction, I think I compress a lot of stuff. My games I think are hopefully…dense in a certain respect? Where there’s a lot of stuff happening, and then after two or three minutes you’re like, “Woo, what happened?” and then you say I gotta smoke a cigarette or something, right.

[From audience:] Two minutes!

Right? A lot can happen in two minutes, hopefully. I don’t know.

Audience 4: My question to you is, when you want to think about a game or when you think about a game’s mechanics and you want to explain the game through play—no dialogue, anything like that—what is the inspiration when you think of your [inaudible]?

Lantz: Yeah, inspirations for level design in games.

Yang: Oh. In level design.

Lantz: Still something you’re well-known for, although your own games don’t have big levels typically. But you’re known as kind of a real insightful critic of level design.

Yang: I’ve kind of— Like, if you’re talking about how other video game levels affect these sex games, I would say they’re not— Other video games aren’t really the big influence for the level design of my recent games. Like really, I think of every game I make almost as like a music video now, kind of. And I just watch a lot of music videos. Like I waste a lot of my time on YouTube just watching music videos a lot.

But in terms of level design, I’m just really… I think my favorite level maybe is a level called The Cradle in a game called Thief 3. And Thief 3, if you were to play it maybe just get Thief 3 and then down a save game that lets you go The Cradle, because the rest of Thief 3 is like, okay. But The Cradle’s really really good. Because it’s this abandoned monastery that turned into an orphanage, that turned into like a mental asylum. Which leans on really lazy tropes about mental illness. But at the time, I was totally unaware of those problematic elements and I was like, “Oh wow, this really dense, ingenious…” Because there’s just… Like in that level… No, I don’t want to spoil it for you. But it plays with the rest of the mechanics in the game in a way that no other level does in that game. So I think I really like levels that are just very different from the rest of the game and that stand out like that. I don’t know, does that answer your question?

Lantz: That’s a good answer, I think.

Yang: Is that good enough? Sorry.

Lantz: I think it is.

Audience 5: I thought it was really interesting to find out that you had an English degree. I noticed your games have a lot of tactile and visual communication. Are you not interested in the verbal, or is that something you plan on exploring? Like dialogue?

Yang: Yeah, some of my games have a little bit of dialogue. But I usually stay away from it just because that means I have to like sit down with a voice actor and record all that stuff, to get to the production value I want, to like mock AAA production value. So it’s like really…narrative is expensive sometimes. Especially in the way that I want to practice it. So I think I’m avoiding it kind of, for a little bit.

But one day when I do have infinite resources or some like, [to Lantz] delicious NYU grant money or something? Like, my most favorite novel of all time is Mrs. Dalloway. And my goal in life, in 2023 when Mrs. Dalloway goes public domain, is to adapt the crap out of that novel and make this really weird experimental, weird AAA with all this voice acting and crap like game that’s just super dense and and lyrical and captures the style of that novel.

But for now, I’m also kind of practical and thinking I can’t do that right now. I’ll just have gay sex instead.

Lantz: Well, with that I think we’re going to wrap it up. We have No Quarter, right? You mentioned No Quarter. So, No Quarter is an annual exhibit of games that the Game Center commissions. Robert, you’ve been curating No Quarter for the past few years. So when is that happening and where can people go check it out?

Yang: It’s happening on November 3rd in Bushwick. So you know, mark your calendars. And we have a really great lineup this year. We have Auriea Harvey, she’s half of Tale of Tales. They famously quit video games, until they got a call from Robert Yang…

Lantz: Yeah.

Yang: We also have Kitty Horrorshow, as is I talked about before. She’s making a really cool piece that’s really creepy and unsettling, but like in the good way. We also have Pietro Righi Riva, and he’s half of an Italian design group called Santa Ragione. And they made a game called Mirrormoon as well as Wheels of Aurelia and all this other stuff. They make really cool stuff, and he’s making a game for us as well. And then we also have Droqen. Droqen you may know, he made Starseed Pilgrim. And Droqen’s making another game for us.

Lantz: And how do people get on— Do they have to RSVP? They go to…?

Yang: Oh, right.

Lantz: Yeah, they go to the Game Center web site—

Yang: gamecenter.nyu.edu, the poster’ll probably come up, and then you click on that.

Lantz: November 3rd. Where do people go to get your games? Steam?

Yang: Yeah, you can go on Steam—

Lantz: Type “gay sex” into Steam and you—

Yang: Just search “Robert Yang gay sex” and you’ll get all my games.

Lantz: And your latest one is The Tearoom, but you have like half a dozen games on there. So check them out. You’re the best. Thank you Robert.

Yang: Thank you.