I’m very very happy to be here. I was invited here, I think, to talk to you user experience designers, because there’s a sense that the UX community might have something to learn from the games community, which I am already questionably representing.

I think that might be true, but there’s another truth. It’s a secret that I’m going to make not so secret, and that’s that we games folks still actually have a lot to learn about ourselves. One reason is that we don’t actually have a very good handle on our object of interest. “What is a game?” for example.

What does it mean to play one? Sometimes we even talk about this idea of “gameplay” which is a sort of nickname for the experience players have when they play a game, and all of these concepts are really loose and circular. No one really agrees on what they mean. So they offer enough meaning that we can use them casually in ordinary conversation, but not to really use them professionally, not to understand what’s going on when we make and engage with the kinds of media that we call games.

If you think about it, you’ll realize that this is the case. Can you really tell the difference between a game and an app these days? What is that difference, exactly? Do you know when something is being played versus when something is being used. What is that difference?

This is the worst of the lot, this word, and it’s what I want to talk to you about today. Because “fun,” after all, is the feature that is supposedly endemic to games, and it’s the one that designers like yourselves sometimes want to extract from games and apply to web sites and apps and whatever else. You know, “make it fun.”

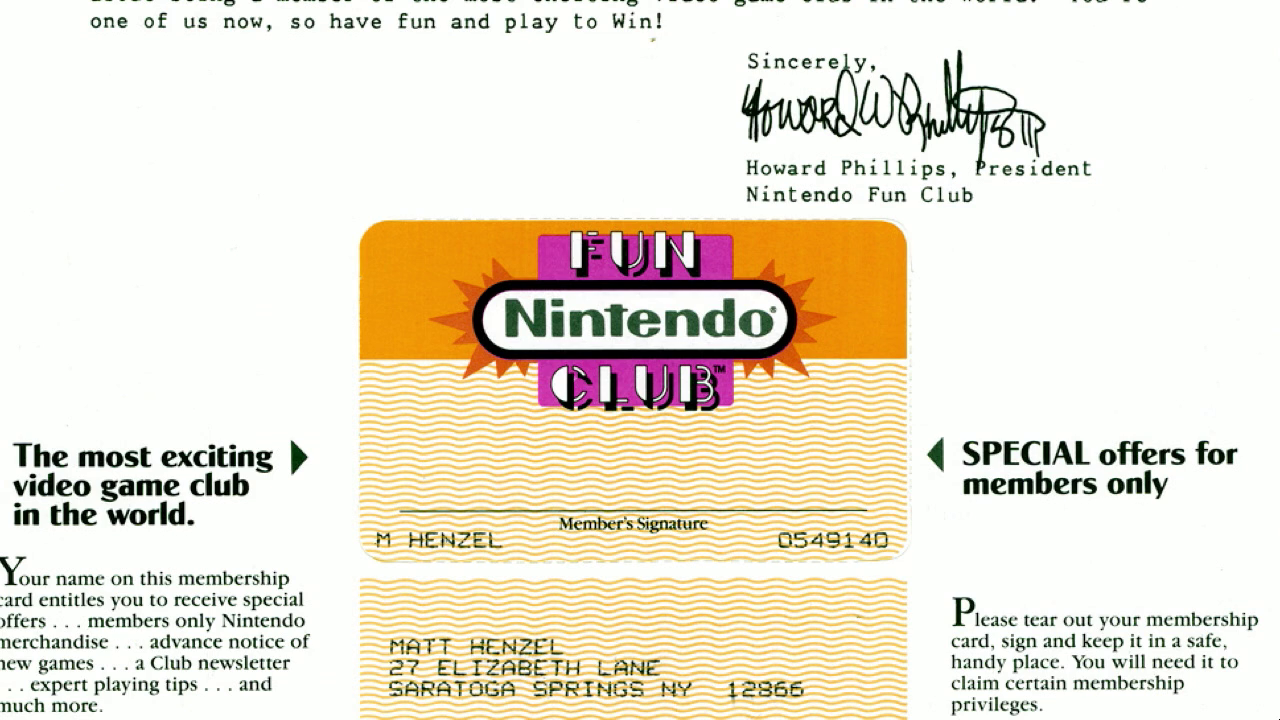

In the world of game design, fun is taken as a given. It rules as an assessment of artistic quality. A game has to be fun, we say. In fact, that sentiment, that statement, is one that could easily be made by an adolescent boy on an Internet forum or by Nintendo’s CEO in a keynote before 20,000 game developers at our annual conference which takes place right across town.

If “fun” just indicates that a product is sort of any good, then I guess it’s a reasonable sentiment but it’s also a kinda mercilessly vacant one, right? I mean, the unexamined weirdness of these terms seems to go under-discussed.

The weirdness of concepts like “fun” and “game” were most effectively summarized by one of the most well-known 20th century philosophers of play, Mary Poppins. As you already know, in “A Spoonful of Sugar” the Victorian nanny opines on all of the different ways that a spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down. You’re familiar with this, you’ve heard it over and over. It’s kind of cloying.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vLkp_Dx6VdI

But despite the apparent joy that this sentiment produces in the Banks children, we ought to remember that they are not real. They are fictional characters that have been scripted for a film. They’re not actually responding to Mary Poppins’ proposal through some sort of test of logic or experimentation.

In fact, it’s good to closely read our Disney films. She only offers two examples of her theory, if we can call it that. There is a robin that sings a song while collecting sticks and twigs to fashion a nest, and a honeybee that enjoys a sip of nectar while buzzing from bud to bud. And these are metaphors, right? We have no reason whatsoever to believe that the robin or the bee get bored or impatient with their tasks. Besides that, she’s not even right. The way that bees work is that they store nectar in a pouch that’s called a crop, and then they regurgitate it back when they get to the hive… Is this the model that we want to use for clean-up with our children?

So we should already be suspicious of the magical nanny. If there’s anything I want you to take away from this talk, it’s that we hate Mary Poppins. But robin and honeybee notwithstanding, “A Spoonful of Sugar” actually offers much less advice than it seems to. It essentially recommends covering over drudgery. Just as the robin’s song hides the supposed boredom of nest-building, so the Poppins song hides the boredom of clean-up. And this works great in a musical, because the clean-up itself is simplified, it’s abstracted, it only takes up as much screen time as it needs to. But real effort can’t be so easily conducted. You can’t just continue singing “Spoonful of Sugar” choruses until you’ve cleaned your house. That would be awful.

In the world of educational technology, we sometimes call this advice “chocolate-covered broccoli.” Chocolate is awesome. We love chocolate, but it’s not good when it you put it on broccoli. Or rather, the sum total of the broccoli with chocolate on it is awful. Like the robin and the bee in the song, it only sort of symbolizes the practice of making unpleasant things enjoyable. You can kind of talk about trying to make something awful taste better, but it doesn’t really prescribe a method for how you would do so. And then when you test it out, it fails.

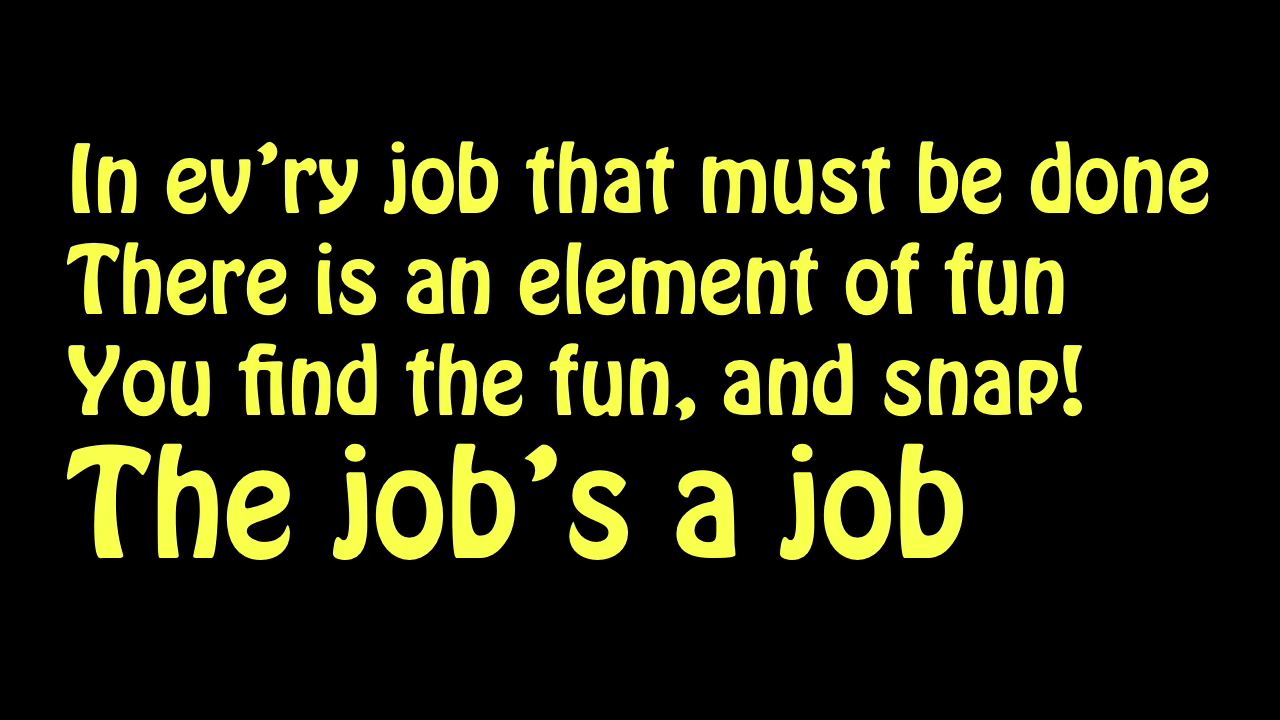

Here’s what Mary Poppins actually says:

In ev’ry job that must be done

There is an element of fun

You find the fun, and snap!

The job’s a game

This is a lovely little lyric. At first blush it seems like terrific advice. But just try to follow it, actually. I can’t believe I’m the first one to point this out. If an element of fun is hidden in every job, then how do you find it? Where do you look? By what process, beyond this sort of supernatural snap, does the job become a game?

“A Spoonful of Sugar” actually offers an entertaining pointer to something that we already know, which is that things are more enjoyable when they’re not less enjoyable. A job seems like more fun if it’s more fun, so…make your jobs fun so they’ll be fun.

Incidentally (and I’m not going to talk much about this) this is also the kind of logic of a trend known as gamification. Games are fun, so let’s add games to things that are miserable, and it’s kind of shame on us for falling for this. It’s the same as Mary Poppins’ snake oil. We’re just trying to dupe people that don’t know any better into doing our bidding.

But I think the fundamentals of this problem come from the word “fun” itself. It’s a word that we use indiscriminately, without knowing what we’re actually saying. And that’s not in itself bad. There are a lot of words like this, more than we realize. Much of our ordinary speech is just automatic, functional. It’s not really deliberate or expressive. So when someone says, “How are you?” they don’t actually care how you’re doing, they’re just saying hello to you. It’s a functional act. Then when you reply, “I’m fine,” you’re sort of acknowledging “yes, here we are together speaking and I acknowledge your existence.”

Actually, this works even with seemingly momentous phrases that get deflated. The first time you tell someone “I love you” it feels momentous because it marks some new level of intensity or commitment in your relationship. But then months or years or decades later, “I love you” works more like, “How are you? I’m fine.” It kind of reinforces an expected state of affairs. It says everything’s okay. In fact, over time, “I love you” only means anything when it’s withheld, when you expect to hear it and you don’t.

Fun is kind of like that. It’s a placeholder more than it is a description. It’s sort of like, “How are you?” When someone asks, “Did you have fun?” it’s mostly a courtesy. Yeah yeah yeah, we had a good time. And in common parlance, it kind of suggests, like “How are you; I’m fine.” that everything went…okay. There’s nothing we need to report on further.

But weirdly, as an aesthetic assessment, it sort of works similarly. So when you say, “This is a really fun game” it’s sort of like saying “This is a good book. It was a good movie.” It’s a generic, slightly positive, but basically empty sentiment that does little more than kind of endorse the speaker’s unexamined, imprecise feelings about something. And it may even do less than that for games, because other media don’t tend to enforce a single meaningless, almost immeasurable metric for aesthetic value. What critic or creator or consumer, even, would take art seriously if its aesthetic ambition was something as vague as “being good?” This is clown town, right?

If we want to be more generous, we might say that fun is a surrogate term for some more complex yet unspoken sensation of gratification and satisfaction, rather than as a kind of description for that satisfaction. And that stand-in could be replaced by any number of varied emotions. It’s sort of like a pidgin. Fun is a way of translating actions into emotions, but we never fully complete the translation. I think that’s also why designers like you folks are maybe slightly mistaken to be interested in games on account of their ability to deliver fun or engagement or whatever the hell it is that we deliver.

Or at least your interest in games may be slightly misplaced. The thing that you might think is a kind of black magic of engagement or enjoyment turns out, maybe, to just be the kind of ordinary practice that only seems exotic when it’s unfamiliar. There’s a kind of Orientalism in the interest in games among the design community. Asking how you can harness fun in your design practice might be a bit like asking “how can you harness umami in your design practice.” It’s just a mixed metaphor, it doesn’t quite make sense.

But the weird thing is that fun turns out to be unfamiliar like this not just in the design context, but kind of in every context. No one has any idea what they’re really saying when they talk about something as being fun. In fact, even the origin of this word is murky. We can’t trace it back philologically and gain much ground. It seems to be really uniquely English, which is interesting, and there’s a Middle English word “fon” which is related to the fool, to be a fool, to make a fool of. And that’s a meaning that we sometimes use, “don’t poke fun at me.” But it’s far less common than the usual sense of amusement or enjoyment that we’ve adopted today as a way of describing fun. Fun used to mean a particular kind of jocularity or diversion, one meant for or done specifically by fools.

Commitment

Fools and foolishness we usually think of as negative traits, but they don’t have to be so. Imprudence may actually characterize one aspect of the fool or the jester or the trickster. But the flip side of that, if you think about it, is a kind of commitment. That may sound strange at first because we normally opposed indiscretion to commitment. But fools can have their own shrewdness, their own way of approaching things. Instead of toeing the line, instead of maintaining the standard way of things, the fool asks “what else is possible?” and then actually carries out that other thing that’s possible, even if it’s outlandish. And the surprise of foolishness arises from this exploration rather than from being witless, from not knowing what you’re doing. The fool finds something new in a familiar situation and then shares it with us.

So think about it: a friend returns from an evening out.

“How was your night?” you ask.

“Fun. We had a good time,” she reports.

What does she really mean? Even with the same friends, at the same bar, with the same hot wings, and the same complaints about the same co-workers, the evening resulted in some new discovery. The way that a particular sense of humor responded to a particular story. Or the way that a face blanketed a new worry with some kind of familiar gentleness. So just like I love you, “We had a fun time” is a kind of compressed shorthand. It’s a way of telling a story without telling it.

This is where Mary Poppins leads us astray. The spoonful of sugar covers over something, it tries to hide it. It tries to turn it into a lie. It assumes that the situation itself is always insufficient; that it is never capable of holding up to scrutiny; that we’ve already figured out everything there is to determine about it and that thing is negative; it’s wanting. And that sing-song job works in a movie, but if you face a challenge like this in real life (a big messy room or a long boring flight or whatever it is) then the song and dance number just becomes an affectation. It’s just an adornment.

Then we feel guilty about that because we were weaned on children’s stories like Mary Poppins, that taught us that meaning comes from outside a situation, from what we make of it. That it has to arise from ourselves. That we have to manufacture it, otherwise we’re ungrateful or lazy or something. And it’s not just a problem for children. In their book All Things Shining, the philosophers Bert Dreyfus and Sean Kelly talk about this exact same issue in the context of the depression and madness of our secular age. They argue that meaning today has to come from within because we’ve forgotten about God so we can’t just choose the arbitrariness of theology, and that this demand to make something wholly from scratch by sheer force of will is slowly eating away at us. It’s driving us insane. David Foster Wallace becomes a sort of martyr for this cause in Dreyfus and Kelly’s book.

So along with Mary Poppins, we assume that finding the fun is a task that comes from us rather than from the thing itself and we just have to encourage or support that activity. We have to bring something to the table that makes intolerable things tolerable, or we have to somehow cover over those things so as to make the intolerable things tolerable.

But what if that’s wrong, what if it’s just the opposite? What if we arrive at fun not through expanding the circumstances that we’re in in order to make them less wretched, but actually by embracing the wretchedness of the circumstances themselves? This will feel very counterintuitive to you. What if, in a literal way, fun comes from impoverishment, from wretchedness? What if it’s in the broccoli without the chocolate?

The philosopher Bernard Suits argues that playing a game is “the voluntary attempt to overcome unnecessary obstacles.” A game is something that’s good enough on its own, something for which on-its-ownness is precisely the point. Suits calls this willingness to accept the arbitrariness of a game the “lusory attitude.” We have to adopt this lusory attitude and accept the thing for what it is. So golf would be worse than a good walk ruined were it a Broadway song and dance number about dropping balls in holes, maybe, but when we really play golf if we reject it as insufficient, then we’re missing the point of golf. The point is that golf is meant to be annoying and unsatisfactory, and that’s why we like it.

There’s something deeply abhorrent about games, something kind of revolting. But then out of that revulsion comes sublimity, occasionally. It’s not just true for games. When you operate a mechanism like a steering wheel— We sometimes talk about the “play” that’s built into that system, a space through which the steering wheel can be turned before the shaft couples with and turns the pinion at its end. You can find this elsewhere, too. The play of light, the play of the waves, a play on words. The game designers Katie Salen [Tekinbas] and Eric Zimmerman have adopted this sense of play in their formal definition of the concept, which is one that I like a lot, “free movement within a more rigid structure.”

So when designing a game, the question is not how to make it taste sweet, but what sort of structure it ought to be, what sort of structure it can be, what sort of structure it wants to be. And then when we’re playing a game, the question we ask is not how to overcome that structure, not how to reject it and make it something it’s not, but what it feels like to subject ourselves to it. To take it seriously. To really play golf for what it is.

So play turns out not to be an act of diversion, but the work of working a system, of working with it, of interacting with the bits of logic that make it up. And fun is not the effect, it’s not the enjoyment that’s released by that interaction, but it’s a kind of nickname for the feeling of operating it, particularly of operating it in a way we haven’t done before, or haven’t seen before. That lets us discover something in it that was always there but that we didn’t notice, or we overlooked, or that we found before and now we’re finding again.

The colloquial senses of game or play or fun would hold that those activities normally go outside the boundaries of normal behavior, of doing whatever we want. That’s usually what we think of when we play. Don’t play with your food. This is why I think designers are so interested in taking advantage of fun, and why they are mistaken in thinking that fun relates to pleasure or to reward, when it’s really just the opposite. Fun is related to structure, not to effect. So you can’t add fun to something, no more than you can cover broccoli with chocolate. I mean, you can, but it doesn’t work.

You can only craft structures that might sort of excrete fun under certain conditions. There’s this paradox intrinsic in this process, in play. Play is an activity of freedom and openness and possibility, but it’s one that arises from limiting our freedoms rather than expanding them. It’s why golf isn’t just a nice walk ruined. Rather, as Suits put it, it’s like asking us to accomplish something using only the means that are permitted by the rules of the game, where those rules prohibit us from doing so in a sensible way. They prohibit us from doing something efficiently, in favor of less-efficient means, and in fact where those rules of inefficiency are accepted just because they make the activity possible, otherwise you’d just walk up and drop the ball in the hole.

So play is a material property of certain objects like steering columns and language and games. And fun is the sensual quality that emanates from it when you kind of pet it, when you touch it in just the right way. Fun is like an admiration for the absurd arbitrariness of things. It’s a name for the feeling of deliberately operating a constrained system.

Dignity

So rather than valorizing the act of play or the effect of fun, this perspective that I’m describing shifts the frame from play as an activity to play as a kind of condition of certain media, and it shifts the form of fun from that of an experience to that of a kind of exhaust that’s produced when an operator can treat a thing with dignity.

What does it look like when you treat something with dignity? Most of the time it doesn’t look like very much at all, actually. It looks like shifting gears or knitting or playing the guitar. These are things that we take seriously and we respect, and from an individual’s perspective (a player or a user, if you must call us that) means taking something for what it is rather than for what it is not, and then following that conceit that this thing, this absurd thing, is what it is and I’m going to take that to its logical extreme, beyond its logical extreme. “What are all the things I could possibly do with this guitar?”

From a designer’s perspective, this activity of creating fun means conceiving of something worthy of being taken as such and then having the courage to birth that out into the world, which is very hard. Not everything is fun not because we haven’t added fun to it, but not everything is fun because not everything has earned it.

This isn’t really how we think about craft or experience these days. We think that everything has equal right to be celebrated and successful and treasured. But in fact I think the things that we find the most fun, they are not really like that at all. They’re not easy, but they’re hard. They don’t pander. They don’t apologize. They don’t onboard. If anything they resist you. I mean they literally resist you, and it’s that resistance that inevitably lets the fun escape.

So if you want to design something fun, you have to almost let it go. You have to trust that it will pay dividends, or if it won’t you won’t know right away. In that respect, you have to give it time. Fun design is a kind of slow design.

But then every now and then, we get a hint of how deep a system goes when we let it steep long enough and then we sip at it just right. In the summer of 2010, John Isner and Nicolas Mahut played a match of tennis for three days at Wimbledon. This was a remarkable thing if you’re a tennis fan. But it was also a remarkable thing if you’re not a tennis fan. It happened because neither player was able to break the other’s service, and thereby tip the match out of equilibrium. So the players served over one hundred aces each, and as evidence of the levelness of their ability, and maybe the unevenness of their volley games compared to their service games, Isner finally, after days, bested Mahut with a 70–68 final set. That was actually a higher score than the one at the buzzer in that years NCAA basketball finals. This was a crazy match of tennis.

And Isner and Mahut were there; they contributed to that outcome. They were implicated in it. But they didn’t exactly make it. They didn’t fashion it. And yet neither did the Victorian designers of the modern game of lawn tennis. Rather, Isner and Mahut found something in tennis that nobody had found before. Something that was preserved in it, durable even as it was incredibly fragile, like finding a fossil at Pompeii. They coaxed tennis slowly over 150 years, almost, to give up this secret. Because they and those who came before them treated it with such ridiculous, absurd respect, that the game finally couldn’t help but release this secret. And that’s what fun looks like at its best, when the whole world watches an abstraction give up its secrets.

So feeling that something is fun, even in the ordinary and popular sense of fun, it’s a good sign that you’ve given it respect, that you’ve been able to give it respect. And likewise when it doesn’t feel fun, it might be a good sign that you haven’t done or that it hasn’t earned it. I think we’re all guilty of this. We expect things, and especially media, to come to us. We expect them to prove something to us. “Show me that you’re worth my time. My time is very valuable.” But then we don’t give it much chance. “Sorry, there are cat photos to look at” or something.

But maybe it’s the things that don’t meet us halfway, or even partway, that seem not to try, maybe those are the things that are the most fun. The ones that don’t give up their secrets right away, that don’t try to make us feel comfortable. Maybe comfort is more a part of the problem than a part of the solution.

So if we return to our new enemy Mary Poppins it turns out, I think, that the thing that makes the job fun is not finding the element of fun that makes it a game, but finding the element of fun that makes it a job.

Jobs are fun when they are not games, or parking meters or oysters or anything else, when they are exactly what they are, and when we take them seriously. Even if we sometimes can take them seriously by making them into a game. So there’s kind of truth in this tautology “the job’s a job.” The guitar’s a guitar. Really and truly taking something as a unique and discrete thing in the world that is nothing other than what it is, and really making something that means to be exactly what it is, that deserves to be exactly what it is, rather than lying about it to try to gain advantage. Or sometimes (and I know this is hard) not making the things that can never meet that bar for earnestness.

So we fail to have fun, or we fail to kind of facilitate fun, because we don’t take things seriously, not because we take them too seriously. It’s not that we’re not having enough enjoyment. And there’s a kind of weird foolishness or gullibility or even insanity in this practice, but it’s also no surprise if you remember that fools and fun are connected. The fool is infatuated. “I’m a fool for you” we sometimes say. It’s an obsession that’s affectionate and earnest, rather than optimistic and naïve. The fool’s fun is a kind of fondness. It requires devotion and enthusiasm, even infatuation.

And that means that fun doesn’t operate on the time scale of agile sprints or minimum viable product. It’s measured in historical time, and thus it might even be incompatible with the whole idea of product design and development.

So with that in mind, what can you do with fun? Maybe one thing is to respect it for what it is in the same that it asks us to respect other things for what they are. Fun is not a hub you fork or a seasoning you sprinkle on your fast-burn app. Fun cooks slow. It’s a commitment to something that’s largely accidental, and it demands seeking out new novelty within boundaries that have largely been erected for a long time. And when you find it, fun turns out to be not very welcoming. It’s kind of cold. But it’s that cold indifference, almost that stupidity of fun, that makes it what it is, that treats something for what it is.

Fun is a kind of exploration, a way of finding these tiny air bubbles of freshness in something that’s suffocatingly familiar. Fun involves treating things like their existence is reasonable. Having respect for something that doesn’t deserve it but doing so anyway and then occasionally catching sight of it blushing when it opens up to reveal its secrets.

Thank you very much.

Further Reference

Before UX Week 2013, Jesse James Garret posted a conversation with Ian about the topics he would be speaking on.

Prior to 1978’s The Grasshopper, Bernard Suits advanced his definition of games in a short 1967 paper “What is a Game?” [Closed access, but can be read online with a free MyJSTOR account.]

“Gamification is Bullshit” at Ian’s blog.