So, from babies to skeletons.

I grew up in the 1980s, and I grew up with Fighting Fantasy novels, the set that were brought into being by Steve Jackson and Ian Livingstone. For those of you who don’t know what these are (which is probably only a small percentage of the audience) these are a combination of kind of adventure fantasy books. The main thing about them is that they present you as the hero adventurer on some kind of thrilling story. You make choices, you save people, you get to punch quite a lot of strange animals and beasts along the way. And hopefully, somewhere along the line you save the day, in what ever form that takes. But there’s also quite a lot of ways to die. There’s quite a lot of ways for your adventure to end.

I like them a lot. I’m sure a lot of people like them a lot for the same reasons. They gave you a sense of agency in terms of what you were doing. They kind of made you feel like you had some choices on your hero’s path through the world, You weren’t just reading passively.

I got older. I put away semi-childish things. I started learning about science and technology and innovation and the social and the political and the economic sides of it. I started doing work with governments, with universities, and all sorts of bodies around the place and in between. And realized, slightly to my horror quite recently, that the Fighting Fantasy world actually bears an awful lot of resemblance to the way and the stories stories that get told through policymaking, particularly around science, technology, and entrepreneurship.

This isn’t, I think, I’m mostly sure, because policy around science and technology gets made in the department for Business, Innovation & Skills, or at Number 10, or in the White House by various ministers and civil servants sitting down with two dice and a notebook and frantically trying to read a book while getting their fingers wedged in the pages to try and figure out which pathway they should be taking. But I can’t be 100% sure of that one, given some recent decisions.

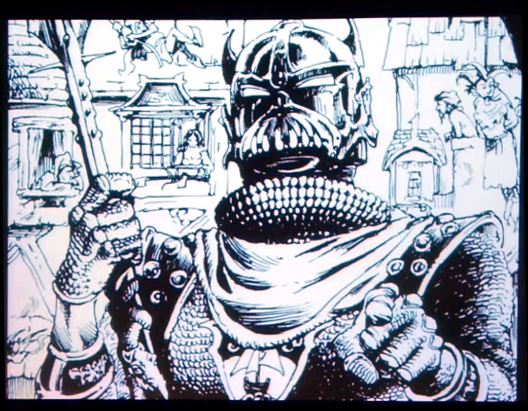

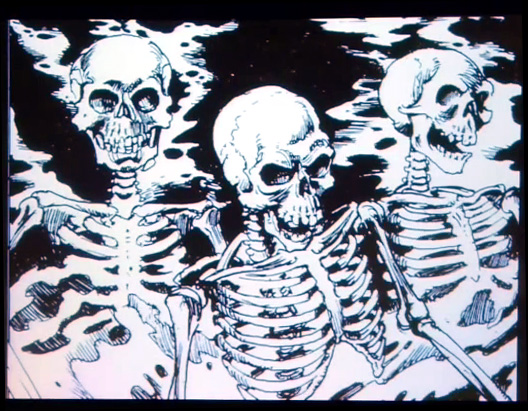

But what I can say is that the worlds that get built in science and technology policy bear a kind of odd and uncanny resemblance to a lot of what Jackson and Livingstone wrote about. City of Thieves was one of my favorites, and it’s actually almost one of the less violent stories, although it still has this hero’s path. It’s set in this world where the merchants of Silverton call you as your adventurer to say, “We’ve got problems. There’s an evil skeleton lord who lives over in Port Blacksand who wants to come over and take over our village.”

There’s kind of a minor subplot about if he really wants to come and steal away someone’s daughter in the standard saving-the-maiden way, but it’s actually quite a capitalist story. The intro is set up around you being brought in to save these very rich merchants. You have a very nice life from this skeleton over there. They’re going to reward you, and they’ll reward you with very nice and shiny things themselves. Zanbar Bone, the skeleton, is terrifying, he’s menacing, he has Moon Dogs who have razor-sharp fangs, and he needs to be defeated. And that’s where you come in.

So this story, again, has echoes in some of the big stories that have been influential in changing the ways that technologies have come into being, a lot of which have been set in play by economists and policymakers over the past 70 years or so.

The first of these stories starts around the time of the Second World War. Just afterwards, when a bunch of Austrian economists started looking back at the fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, at the economic mess at the end of the two wars, at the stagflation that they’d seen, at the bank collapses. And they were thinking, “This has been terrible. How can we prevent this happening again? What kind of policies or futures can we point towards that would stop this from happening.”

The conclusion that they had come to was that what had led to a lot of these problems had been a particularly heavy-handed state, this thing that had been clamping down and causing more problems that it really needed to. And what was needed instead was a way of bringing change and growth into an economic system, but without the heavy-handed state itself.

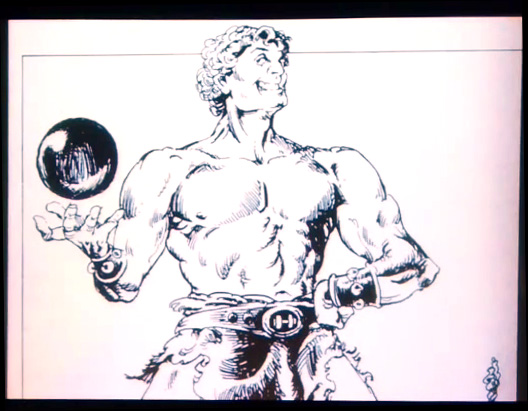

The way they thought that could be done was through entrepreneurship. The hero idea of this entrepreneur started to emerge from the 30s and 40s onwards, but really kind of came into form in the 70s itself. This wasn’t just the Austrians themselves. This was a bunch of economists, Polanyi, Hayek, Schumpeter, later Milton Friedman, who all built this idea, this hero myth of the amazing entrepreneur who would be there to introduce change, save the world.

And it really was a heroic narrative. [John] Maynard Keynes even came on board to say that entrepreneurs were filled with these amazing animal spirits. They would take great risks under conditions of extreme adversity. They would innovate even when conventional economic analysis said that the gambles are too wide. They would leap over that cliff. They would be there. They would be fighting at the front.

This is a very seductive narrative of the hero entrepreneur who will bring innovation and change. In the growing of this myth, the words “entrepreneurship” and “innovation” and “innovative” and almost “creative” as well started collapsing in on each other as well. So you have the entrepreneur who makes new things, who’s innovative, who brings innovations into the world in a bit of a messy way that is kind of ill-defined.

It was a policy and idea that picked up steam particularly during the 80s. Again, it was this seductive idea that you could have this fantastic new world simply by these heroes who would come through and ride on through and bring change with them. Brilliant. And it’s something that persists today, even in the way that business gets taught, even in the language that we see through a lot of science and technology communities about the need to be entrepreneurial, the need to be innovative.

And there’s a problem here, because sometimes stories themselves don’t actually come true. Academics at Sussex Paul Nightingale and Alex Coad, like many contemporary economists, have raised an eyebrow at this mythmaking around the entrepreneur, and they decided to crunch through the numbers in the UK and see what they came up with instead.

In innovation policymaking, you get quite a lot of drawing on animal myths. Not just the animal spirits themselves in the entrepreneur, but you get talk of small firms that grow quickly are gazelles; they leap. Firms that grow big and are powerful and strong are gorillas. This is the language that gets used in policy documents. And continuing with that, Nightingale and Coad when they crunched the numbers said, “Yeah, we’ve kinda got a problem here. We haven’t really got gazelles, we haven’t really got gorillas. If you look at what makes up most of the market in the UK, it’s muppets.” It’s Marginal, Undersized, Poor-Performing Enterprises.

So what we would call entrepreneurial firms or startups and entrepreneurial businesses in the UK, they’re small, they’re marginal, they’re underperforming. They perform more poorly compared to other types of firms themselves. They’re less innovative. It’s not a happy story.

The people who start these firms, the British entrepreneurs, are happier, and that’s good. Again, the agency of working for yourself is fantastic. But that is not the story that we’ve been sold here about how they’re going to save the economy and it’s all going to be magic. “Happiness” is not going to do that. There’s something else going on here itself.

The example that Coad and Nightingale give is a fish and chips shop. They say you want the classic—the most common type of entrepreneurial business in the UK is a fish and chips shop. It’s something that was set up most likely by someone who is unemployed and with their money as a way of creating a business for themselves. It will likely set up in a town where there’s already a fish and chips shop and there isn’t really enough of a market to support another one. So either that shop will go out of business or it will displace the other one and they’ll both go out of business themselves.

So the story is not necessarily true, and this is very recent work so what influence it has on policymaking is unsure. But the language lives on, the stories themselves become real. Particularly the stories themselves are very very heavily colored by the stories that come out of California, the Apples, the Googles, the Facebooks, the things that could be, that could be seen in that way. The Silicon Valley, the silicon word that gets reflected everywhere like some kind of charm.

We’ve got problems as well when we start believing the myths in other places. There is, certainly moreso in the Bay Area, far moreso than in the UK, an awful lot of money swimming around for those who would be in startups, who would want to again create these innovations, who would be these entrepreneurs and go for it in the world themselves. It’s an uneven process. A lot of this money is swimming toward the founder teams and towards the people they bring into them, who are of a particular demographic. And as we heard in the last talk, a lot of that particular demographic is young white men who are often straight out of college and are taking up these huge and terrifying salaries, these large amounts of money to make things on this entrepreneurial dream that they will change the world in some way and everyone will get rich and everyone will be happy.

And weird stuff starts to happen here. Weird, weird stuff. Firstly, when you’ve got these homogeneous teams of people who are all quite similar, who due to some kind of insidious idea of culture fit are not particularly happy or willing to bring in people who are not like them. And when every one of you is all the same, that’s quite a low bar to be setting for yourself.

So the kind of technologies that get made are not necessarily very exciting. They’re representative of the kind of things that this demographic would want, or that they can project out to some other demographic needing but without their direct experience and world-sense. So you get a lot of little digital things, a lot of dating apps, a lot of places where you can find a restaurant, a lot of things where you might be able to track things or track a place to take a date to a restaurant or something like that. It’s something that [Alexis] Madrigal of The Atlantic said, these technologies that are coming out of these startups, they’re nice, they’re cheap, they’re fun. And they’re about as world-changing as another variation of beer pong. This is not big, radical change.

But the belief in it can create change in other ways, in the systems around the Bay Area. In response to this swell of money going into this particular demographic, again, weird things start happening themselves. Ellen Cushing described this change process as something turning into the bacon-wrapped economy, where you’ve got a lot of service provision that starts rising up to support the needs of these people, these young men who are making a lot of money very quickly and at low risk. Remember, not are they the hero jumping over some terrible canyon, but someone who if they lose their job tomorrow, their company goes down tomorrow, there’s likely to be more money; that’s alright.

So you’ve got things like fancy restaurants, but fancy restaurants serving things like fried chicken at $48 a plate. You’ve got things like high-end whiskey tasting. You’ve got things like being able to rent fast cars very easily. You’ve got things like clothing companies that spun up selling types of essentially tracksuit bottoms so that you can wear them to work and not have to be too smart. But sometimes the tracksuit bottoms have got reflective panels on the bottom so you can roll them up and go cycling, and some of them are a little fancier. They’re dress pants, they’re dress tracksuit bottoms if you need to be a little bit smarter at the office one day.

So there’s this weird kind of lock-in to this space in terms of who’s there, what they’re making, the bubble that surrounds them. But this wouldn’t really be happening if there wasn’t any money coming into the system, and that funding stream as well starts to lay on weird problems, too.

If it’s not friends or families, a lot of the money can also come from venture capitalists. Venture capitalists do not exist out of the world, they exist very much in it. Funding and financing is incredibly risky. Most innovations fail. You will most likely die on the journey. You will most likely get eaten by something. So venture capitalists as much as anyone else, they know that most ventures they fund will fail in some way. They’re trying again, to dampen down the risks, to make this into something as low-risk, as less dangerous, as possible.

Part of this is looking to their own experience in ways that do seem to make sense. So venture capitalists who have background experience in large firms tend to fund teams that have a person in them with a background from a large firm. Venture capitalists with a background in small firms tend to fund teams which have in them people with a background in a small firm. Venture capitalists with engineering backgrounds tend to fund teams which have in them someone with an engineering background. So there’s this mirroring effect. But the mirroring effect also takes itself into the culture. There’s a certain way that entrepreneurs and startup kids are meant to present themselves when they go to meet to VCs, which shows them—it’s almost like dating. You’re not coming across as too arrogant and too cocky, but you’re making an effort and you’re trying to reflect in the venture capitalists’ eyes something that they want to see.

So if you’re meeting a VC who comes from a mergers and acquisitions background, the general advice is “wear a tie; they like that.” But on the other hand if you’re meeting a VC from a European background, you don’t want to be too smart because that just looks like you’re trying too hard. That’s like turning up on the first date in a full suit and tie and it’s just really off-putting.

If you’re a girl, if you’re a woman, then Forbes advise you when you go to meet VCs, “if you want to, you can wear a pop of color like maybe an orange blouse or pink skirt.” And that will give the VCs something to remember when you’ve left the meeting. But not during the meeting. You don’t want to turn up as some kind of multi-colored freak, but just a little something on the retina to go, “Ooh, yeah. Okay. We like that.”

What this does is it ends up creating this incredibly weird hall of mirrors effect in terms of what gets funded where the funders are looking into the startups, and the startups look at the funders, and down they go and down they go and down they go until you get to a situation where you have Paul Graham from Y Combinator saying, “I can fooled by anyone who looks like Mark Zuckerberg. We once funded a guy and he was terrible, but I said, ‘How can he be bad, he looks like Zuckerberg.’ ” Money. Money. A lot of money here, kids.

There’s also things which are very very difficult to get funding for, even outside of this little bubble. Things that are untouchable. That even if the technology or the idea is good and money-making, they will not get funded.

Mostly, this is anything to do with sex. Pornography itself doesn’t really get VC funding; it never really has. And it’s odd because this is one of the industries that is very hyped up as being highly profitable. It kind of isn’t, not anymore, but still you’d think given the kind of dross that does get funded, you’d think well maybe it’s a money game. But it’s really not. It’s about the social reputation as much as anything else of what gets funded. So porn companies don’t get funded. There’s financial elements to it as well. They don’t tend to have good exit strategies, but that again comes back to who would buy them. Who would buy them? Who would put their reputation on the line to do that? Even if the VC things, brilliant idea, lots of money, they then have to go back to their boards and say, “I did that, with your money. I funded that. That’s what I did.” And VCs are not willing to take that risk at all.

The interesting mirroring even comes down to clothing. There’s this kind of idea that pornographers are those in fantastic, long leopard-skin jackets or are just very scruffy guys in cutoffs and t‑shirts, which is not really true at all if it ever was. But there’s that idea there. So much so that a financier who spoke to Gawker said, “Maybe pornographers would get funding if they just dressed up a bit and wore nice blue blazers. That might be good.”

So this world exists where the market skews in this way that’s shaped by so many social and political and cultural forces. And actually for all of this, the state has been waiting behind the screen and it’s still there.

Despite all the rhetoric of “hurrah entrepreneurship” and “throw it to the market,” actually the state has funded an awful lot of technologies that are currently in play and have made a lot of money, and have become pervasive, and very influential, and in some cases very controlling as well. Mariana Mazzucato is an economist, and her thesis is basically the entrepreneurial state. She’s done this incredible historic economic analysis where she pins back various technologies and their original funding to their source and says, actually, look at this. If you look at the iPhone, for example, the modern one, look at where the original funding from the Internet came from. Look at where the original funding for touch screen came from. Look at where the original funding for voice-activated technology came from. Look at all of that, and you will find that back down the line there was either basic funding from the state or applied funding from the state, or even some seed funding from the state itself in a sort of fast capital type way. So there has been a role where the state itself has come in to bear the risks that the market, the amazing hurrah free market actually hasn’t been able to cope with.

There’s still a politics at play about what will get funded. Science policy is a politics, as the name itself suggests. It is not just the case that things get money thrown at them and sent out in the world. In policymaking there’s this idea of picking winners which has kind of fallen out of favor because of how obvious it seems. It’s literally what it sounds like. The governments would say, “Okay, so that green energy we will target a lot of money for that. We will fund a lot of students to go and look at it. We will fund a lot of research labs. Or maybe car manufacturing; we will fund that. We will pick those winners.” And it has fallen out of favor because it’s so obvious, but at the same time it’s started to kind of gently rise back in in the past few years, this idea that actually the markets might not be able to do that. There might have to be a bit of a bigger push there going on.

But there’s also more insidious forms of creep as well, these things where even the technology itself starts to cast a very long shadow in what it’s doing, and the direction of that shadow, the shape of it itself is controlled by aspects of the state and also by links with the private sector, too.

The most recent one in the UK was the porn filter that was brought in, or was advocated to be brought in by our Prime Minister earlier this year. This idea that there would be this opt-in that came from ISPs, that if you wanted to look at anything that was pornographic, you would actually have to say, “Yes. I stand here and I would like to look at dirty pictures, thank you very much,” and that would be brilliant. There’s been a lot of furore around this for various obvious reasons in terms of workability, but one of many interesting aspects of it was when people started to dig a little more and looking down at what actually was going to be on that list of things to opt into. It wasn’t just pornography. It was things like what was broadly termed as “extremist and terrorist sites.” There were anti— kinda suicide sites. Web forums might have been on the list? And the fantastically-ambiguous “esoteric content,” which could be defined as anything, really. But that was the kind of controls that were being placed.

But again the way that states can build technology can not only have the same biases but the biases of history built into it as well, and particularly the mythmaking around entrepreneurship and startups and what should be done and how technology should be built and what works. We’ve talked, at this conference, a fair amount about the NSA and surveillance, and there’s been mention of XKeyscore, which is one of the surveillance technologies that was specifically developed by the NSA to allow analysts to search metadata, to look through emails, look through browsers. They could do searches by email addresses, by IP addresses, by names. A very sharp bit of technology, and possibly not a particularly consensual one.

But that was the technology. And of all the things that I found completely fascinating about the way that it got built was the language that the NSA used to describe it. They described how they had built this in-house with a little startup-style team to do it. They had made sure that the developers and the customer support people and the support staff were working close to each other so they would be able to work together on this. They described how they used agile techniques to achieve their surveillance technologies. They described how they worked closely with the customer to deliver (remembering the customer is at this stage the NSA.) And most importantly of course, they shipped code early and they shipped it often.

At the end of City of Thieves, if you’ve done it in one of many right ways, you will come face to face with Zanbar Bone, who in his own little way is a tiny bit like the NSA. As you’re climbing up the black tower at the very end, he calls to you and says, “A ha, foolish adventurer. I can see you, but you can’t see me.” Which raises questions about the kind of surveillance techniques in place around Silverton and Port Blacksand. But you go in, you’re a hero, you kill him. That’s great, you’ve done your job. You go back to the very rich merchants who are very fattened and well-fed. And they give you coins and I think they give you a really nice sword, and it’s brilliant. And that’s the end of your adventure. You are the hero, the hero has come through.

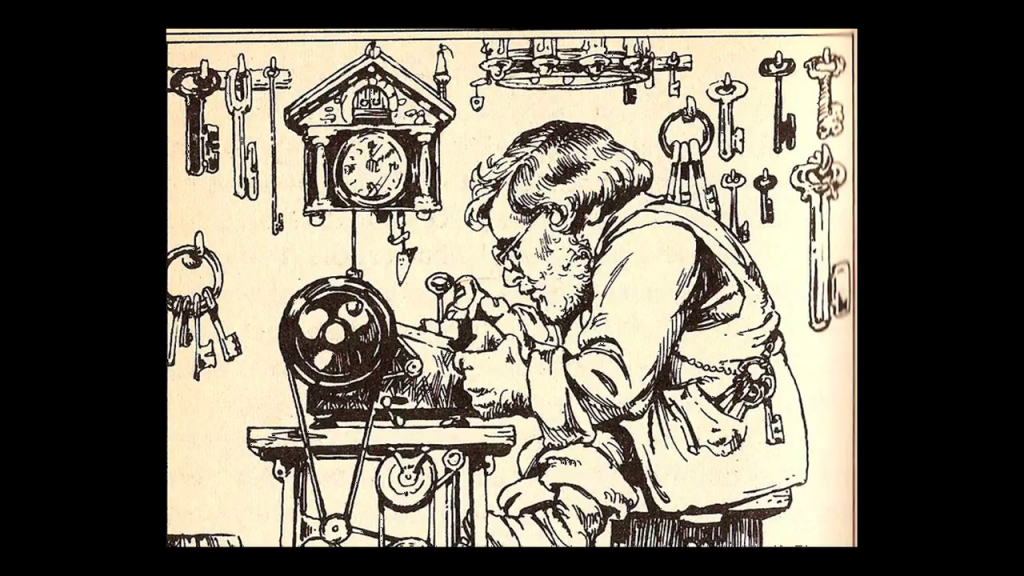

Except when you look back, there are some questions that needed to be asked here. Firstly, what has seemed to be an adventurous quest has actually been very controlled from the outside. There are choices you’ve made, generally along the lines of “Do I go left down Candle Street? Do I go right down East Street? Do I steal this brooch from this lizard?” There are things that you learn along the way, and not just if you’ve got your hands in the book like that, but you figure out where the various routes are that you might draw a map. And there is an element of luck and chance in the dice, but ultimately this is a story that’s been set up by someone else. This isn’t Zanbar Bone pulling the strings from behind the scenes going, “Ha ha ha, if they go that way they will find the table with the scorpion brooches.” This has been set up by a bigger system.

Secondly, if you’ve got to this end successfully and you’ve done everything you need to do in order to finish, you will have things like your hank of hags’ hair, you’ll have your black pearls, you’ll have your lotus flowers. These things destroy Zanbar Bone. You’ll have the silver arrow you need to knock him down as well. You will have killed or at least maimed (it’s never quite clear in Fighting Fantasy) an awful lot of people to get to that point. There’s not really a path that is you skipping around merrily and no one touches you and it’s brilliant, the end. There is generally somewhere along the line, people, sometimes going about their own business. And to get to Zanbar Bone, generally in some iteration you will have seriously wounded a lot of men and women. You will have punched probably a centipede somewhere down the line. There are some giant rats you will have taken out and a lizardine. Most of the creatures you saw in the previous slides are not here anymore, because of you.

But it’s okay. You’ve won. But more than that, one of the things you need to do to get past him is to have on your forehead a tattoo of a white unicorn and yellow sun. And there you are marching around like some kind of terrible hipster with this thing on your face. And you’ve won. Brilliant. But you are transformed. You are transformed by what has happened.

There’s a way to describe the way that technologies come into the world by Frank [?]. He calls them “hopeful monsters.” The technology comes into the world hopefully, because it wants to change the world, but it’s a monster because actually it’s not familiar and it’s not right for the world it’s in. And one of the things from policymaking and from Fighting Fantasy is the monsters are not born that way. Technologies are made monstrous by the processes they have to go through, the ways that they get skewed, the people who are allowed to [work?] them, the paths to funding, the places where government approves or doesn’t approve of them, the locations they’re adopted into. There is a skewing and messy way where the larger political and economic and cultural and social systems create this monstrous being that emerges into the world, and it’s not the monster at the end of the game. It’s the game itself.

Thank you very much.