Ijlal Muzaffar: Hello everyone. My name is Ijlal Muzaffar. I am associate professor of architecture here at RISD. I’m also the graduate program director of our other degree, Global Arts and Cultures, which was launched with NCSS and it’s just as involved this conference and the things that it’s dealing with.

So my job is easy. My job is to just introduce the speakers of the spectacular panel that we have now. You can read the description, it’s called Architectural futures, public infrastructure + the Green New Deal. I’ll summarize it in words paraphrasing Damian, which is, does architecture give a damn? So, we’ll find out. I think it does. But it has an uphill battle. So, to discuss this I’ll invite, and you can read again their detailed bios in the packet that you have but just to give a very brief summary, Bill Fleming, who’s research coordinator at Ian L. McHarg Center at UPenn; Peggy Deamer, professor of architecture at Yale and The Architecture Lobby; Daniel Barber, professor of architecture at U. Penn; and Liliane Wong, who’s professor of interior architecture at RISD. So please welcome.

Billy Fleming: Good morning. Give me one second while I orient myself here. I just wanna begin by thanking Damian and everyone else here at RISD for having us and for organizing this incredible event. I’m sure those little cheers in the back were all the students I’ve driven from Penn into coming up here while I’m here so thank you, you’ve fulfilled your contractual obligation to cheer for me.

I think that Damian asked me here in large part to talk about this essay from last spring in Places Journal that begins pretty timidly with this line, I don’t know when the myth of designers as climate saviors began, but I know that it’s time to kill it.

Which as you can imagine got me invited to lots of dinner parties at Harvard. So I’m going to talk a little bit about this piece and some of the things that went into it. And I’m going to talk about some of the work that’s been underway within the McHarg Center and elsewhere around the Green New Deal sort of since this thing went live.

And I’ll begin with some of the myths that I sort of set out to challenge a bit in that essay, sort of design and designers as agents. The so-called agency of landscape and the centrality of design to the struggle for climate justice, which…we’re canceling. And the notion of design and designers as a sort of mystical practice, the work itself a product of lone, creative geniuses cloistered away making change, or as some colleagues up the road from here suggested earlier this year in an exhibit, somehow making social change through maps and images. Which we’re also gonna cancel.

And in their place I offered what I think many others have argued in allied fields for a long time, something that folks who do not spend a lot of their time in elite design schools read and said, “Like no shit.” Which is that—and what Ananya Roy, Neil Brenner in urban planning, Peggy Deamer who’ll follow me here and Keefer Dunn in The Architectural Lobby and others have said for a long time, which is that design is in fact none of these things, it’s merely an instrument for power. And that who wields that power is the boundary that sets how landscape and architecture and planning are expressed in the built environment.

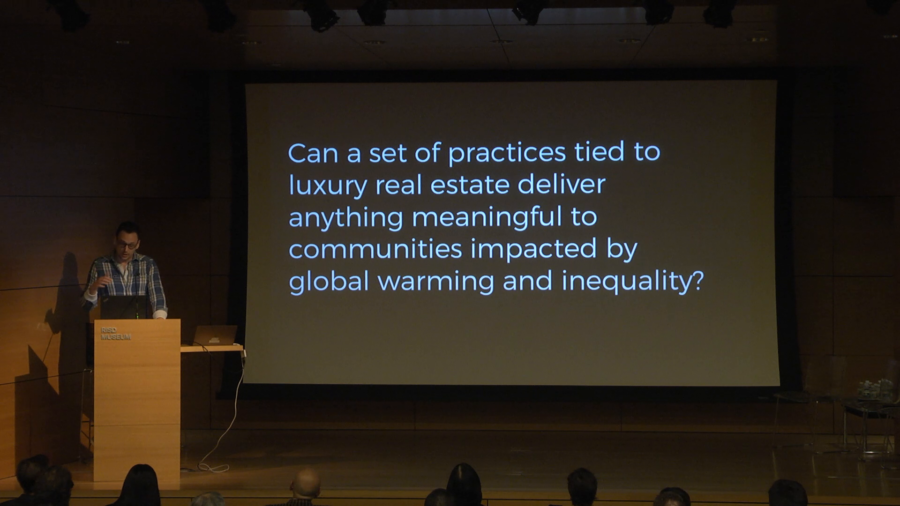

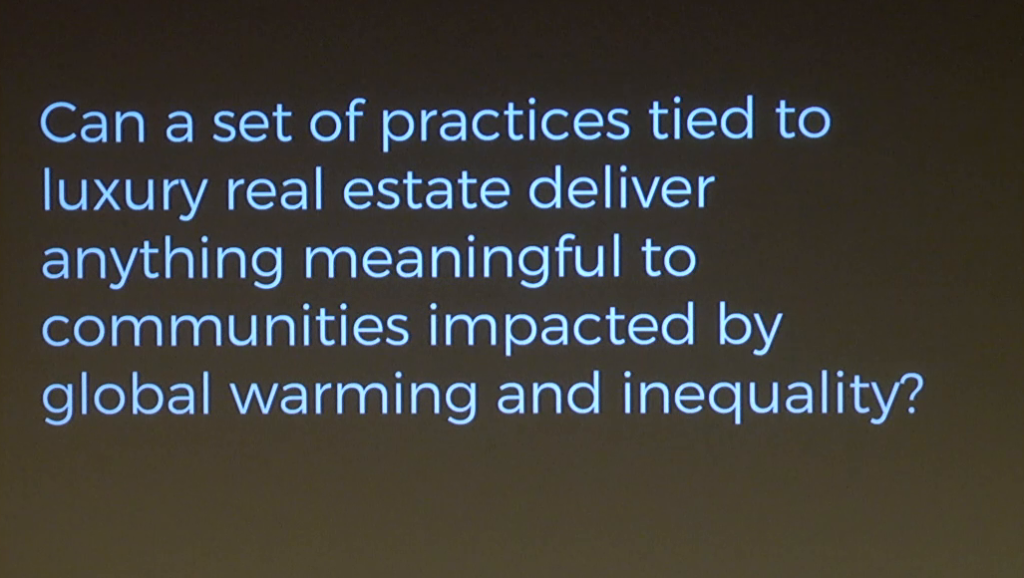

And among the many questions I asked here, and some folks who’ve benefited immensely from the rise of neoliberalism and the financialization, privatization, and depoliticization of our fields who I think viewed it as maybe a bit too provocative and perhaps striking the wrong tone, partially because they felt it as an attack on all of the sort of wealth and benefits they’d built for themselves over the years, something I think is increasingly important to a rising generation of designers caught in the myriad traps of precarity and downward mobility set by this prior generation of designers who have found comfort and material wealth in their relationship with capital. This to me seemed like the only question that mattered for the rest of my time in this field. And namely, can a practice tied to luxury real estate and urban development deliver anything meaningful to communities impacted by climate change and extreme inequality? Or to put it another way, can design be both an instrument of neoliberalism and an activist force for good in the struggle for climate justice? And I think the answer to that is pretty obviously no.

And so I don’t mean to say that designers aren’t doing good or interesting work. I think quite the contrary. There are plenty of good pilots and demonstration projects out there. Rather I wanted to argue that we would be hard-pressed to look at the world around us beyond the cloistered worlds of places like Penn and Harvard and RISD and to believe that things are largely fine, that these projects are in and of themselves enough. And that we are but a few small tweaks away from where we need to go. And that ultimately there are only dead ends for us in the sort of professional structure tied completely to the whims of capital and elite clients. And that we’re left with this sort of creeping sense that we’ve been sold a discipline or set of disciplines whose tools, operations, and modes of practice are fundamentally misaligned to the goals that we’ve set out for ourselves.

And I’m not gonna belabor this point too much. This is a thing that everyone, if you have not read should read at some point, Alexandra Lange’s…the last in her series of retrospective book reviews of some of the canonical architecture books of the 90 and early 2000s. This is from Koolhaas’ X…S, M, L, XL—which I can’t believe I said that right, I’ve never said that right the first time—where she asks in here could Rem have used his stardom to do the things that we all sort of I think and hope architecture will do in the next ten or twenty years, which is to use his stardom to refuse competitions, to establish parameters for equitable practice, to set a forty-hour work week, not to work with authoritarian regimes. Could he have? Maybe. Did he? No. And I know Peggy will talk more about this but this is one of the challenges before us now for folks at places like this.

And so, if we take this critique seriously that design is and always has been an instrument of power not an agent of change, then we must also begin to view our role in the academy as something more than simply trying to chip away at the worst effects of climate change and capitalism. That instead what we must do is develop and offer a viable alternative to design practices structured entirely around flows of capital and elite whims. And that what we must begin to build together through these different networks that Damian and others are beginning to build is an anti-capitalist counter-hegemonic block aligned with movements and not with these similar bodies of clients. And for us, the single and only big idea on the table in that regard is the Green New Deal.

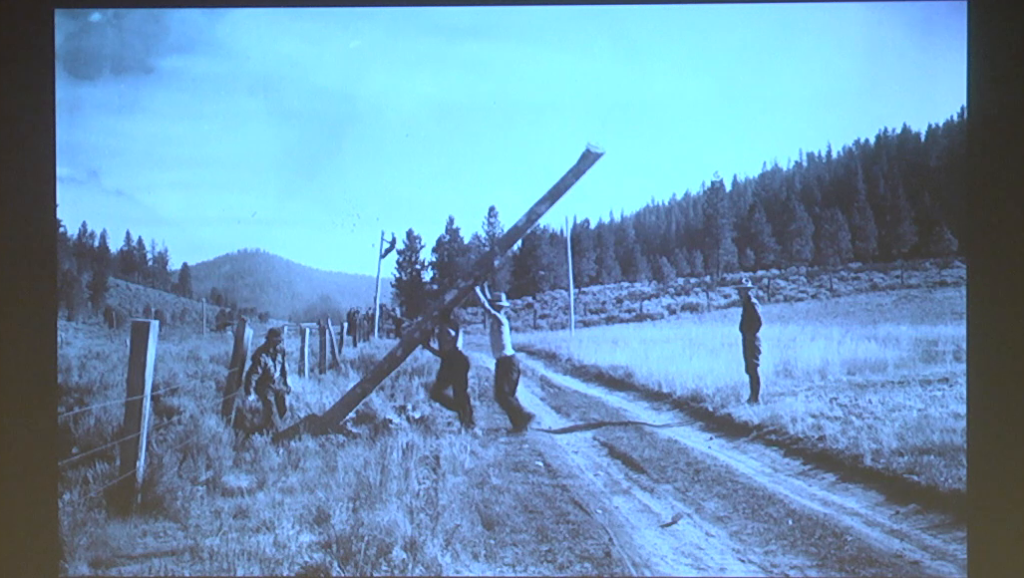

And to do that it requires that we recover and produce new histories of some of the moments in this country’s history and in global history when power has been wielded by different actors and wielded well. We were looking at Red Vienna, we’re looking at an image here of CCC workers during the New Deal. And we have to begin to tell more fulsome histories of the sort of canonical projects that our fields hold up.

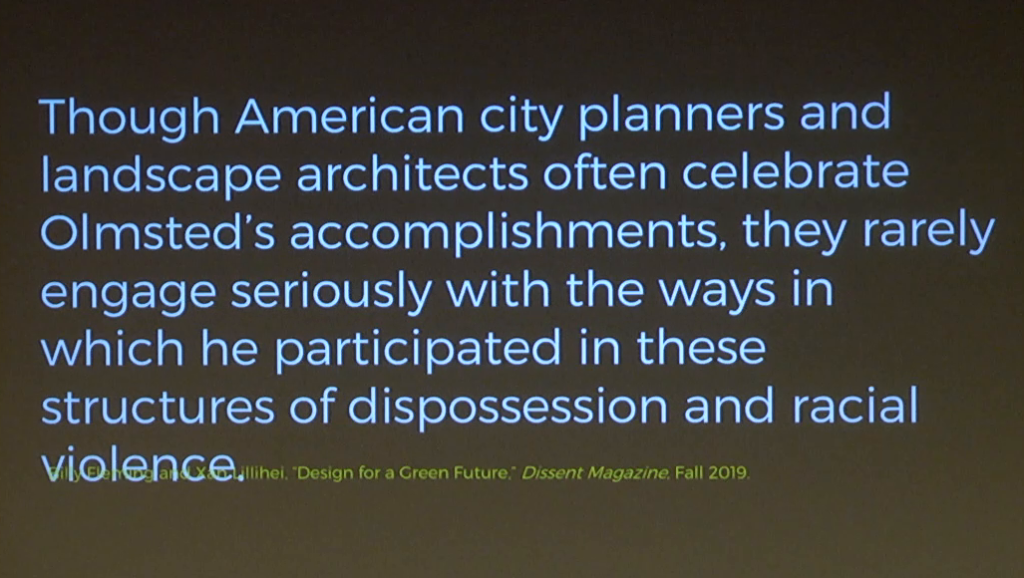

Design for a Green Future, Billy Fleming & Xan Lillehei

This is—I don’t think she’s here. Xan Lillehei, who’s a grad student who’s done a bunch of work with me. This is from an essay she and I had in Dissent magazine earlier this year. The text is a little wonky going from PC to Mac, sorry about that. But we should begin to tell some more fulsome histories about people like Frederick Law Olmsted and his Central Park, the canons that sort of bound our fields or shape our fields, and to talk about him and certainly others as the product of their willingness to collaborate with racist city elites and developers and evicting the black residents of Seneca Village to make way for the ultimate bourgeois park, Central Park.

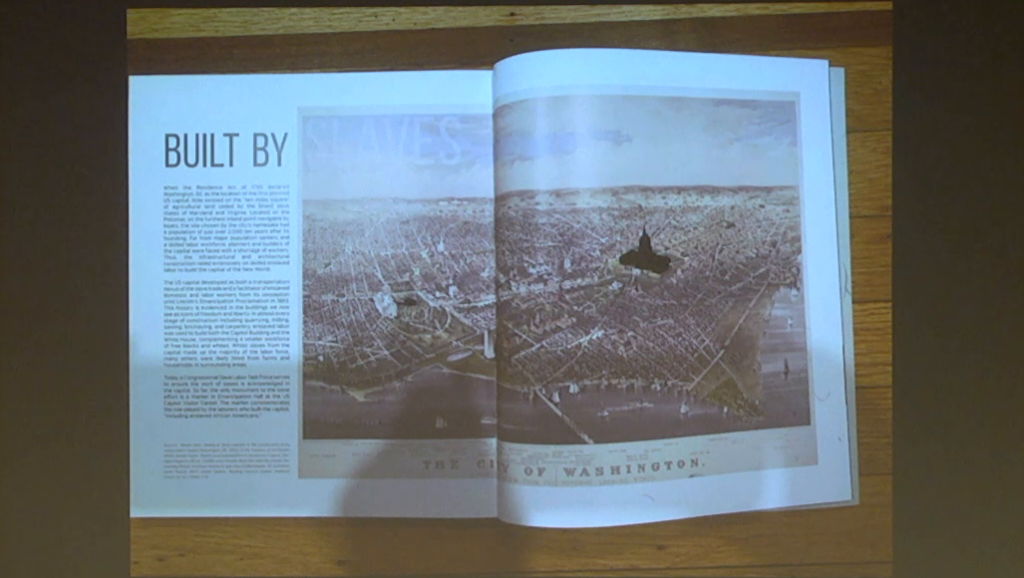

And even within the New Deal (we’re looking at DC here), the willingness of planners and architects within the Farm Security Administration to dispossess black farmers in the delta to make way for white landowners seeking to consolidate and industrialize agriculture in the rural south, processes ever long underway before the New Deal but that accelerated during it. And the pervasive use of slave labor in many of our nation’s sort of iconic cities. This is from an an old issue of LA+ showing the buildings here built by slaves in Washington DC. These are not histories that are often taught in our core history and theory courses at design schools.

And as I also wrote in that essay anyway, the Green New Deal represents the biggest design and environmental idea in a century for us. And it largely has materialized without us. As Damian sort of alluded, this is an idea that’s been put on the table by movements and organizers struggling for years and years in obscurity to create space for people like us to come together and talk about this sort of an event, or these sort of ideas in a context like this.

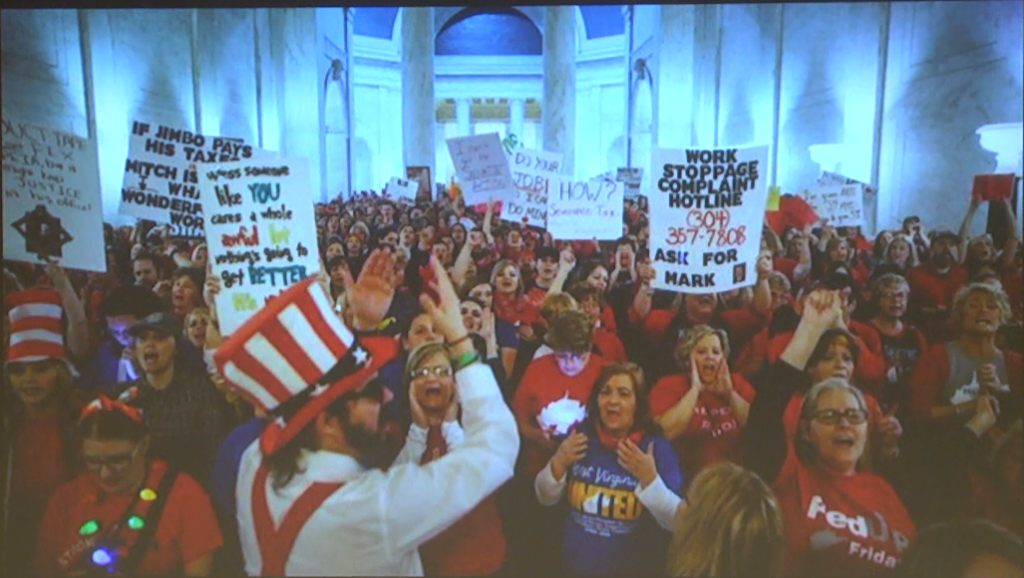

So, if we look at— This is coming from the protest Damian mentioned. And we can already see some of the opportunists within our fields, out in the design fields, clamoring to sort of steal these ideas for themselves, either in perpetuation of their own personal brand or in the sort of constant seeking of business development opportunities for their firms, willing and looking and eager to say that what they do is already the Green New Deal so send us more money to do more things we already do.

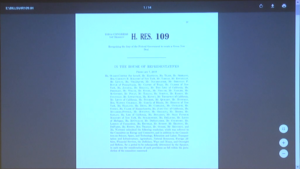

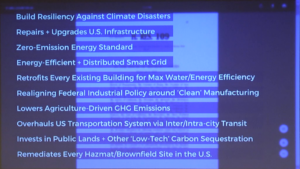

Now, others in this field have also taken a position I think that the Green New Deal as currently formulated is missing certain things. So we-re looking at HR 109, a sort of framing document here. And that because they looked at it, it’s missing some things that their particular sub-sub-sub…sub-field of their discipline cares a whole lot about, it has to be canceled, it’s over. Or they’ve read it and concluded that the Green New Deal sort of already exists in the way that they practice and nothing really needs to change. I’ll say for us—we sort of came to this in the McHarg Center…with the idea that I think what most people would understand represents a sort of framework. So if we look at the various built environment aspects of HR 109, some of which are up here on the screen, we can get a sense that like, this is to be viewed as a skeleton to be filled in. This is what we’ve been doing now, with a group of public housing residents organized mostly by People’s Action and the Homes Guarantee, and a number of other people who’ve been involved in sort of crafting the policy framework for this going forward. And I feel like I would be in very big trouble and remiss if I didn’t mention how much of this work has been produced in partnership with Daniel Aldana Cohen, my work husband and like, housing dad at the University of Pennsylvania.

So, I’ll mention that stuff briefly in a moment. I’ll come back to the Green New Deal work we’re doing. But I think we also have to begin with its primary reference, the New Deal and talk about what we can learn and we can not from that, since these movement folks have told us that you know, through the Green New Deal this is where we have to begin. And so the New Deal for us anyway represents probably the last moment in this country when there was an alternative on offer in the design field to the sort of elite and private capital-led practice of architecture, landscape architecture, and city planning.

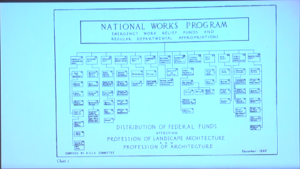

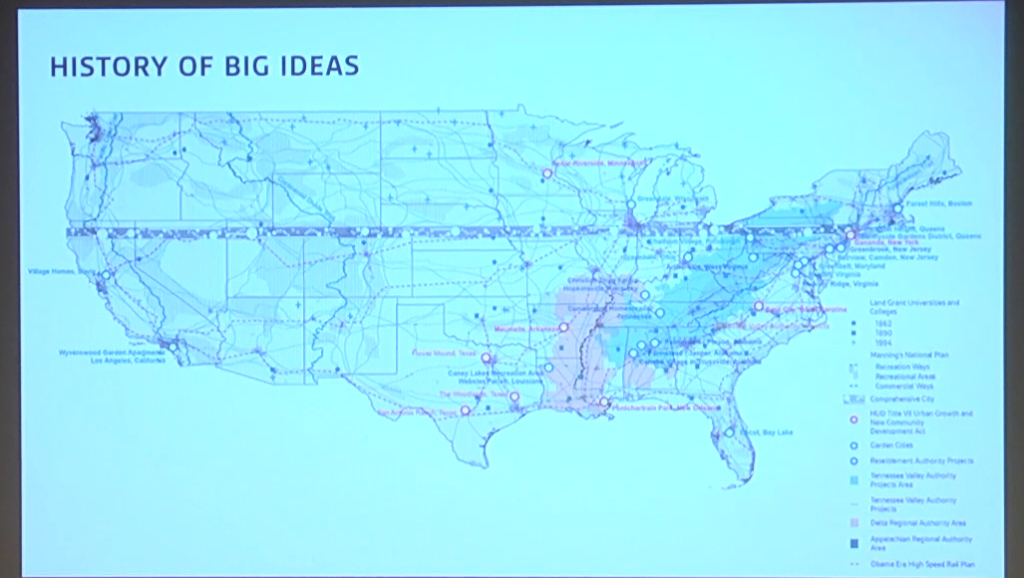

And beyond introducing universal programs like Social Security, the New Deal also radically reshaped the physical landscape of the United States. We’re looking here at The Living New Deal’s sort of mapping project showing about 15,000 of the 55,000 or so built environment projects built by the New Deal. And you know, this is create for us what Phoebe Cutler sort of called her book The Public Landscape of the New Deal a designed bureaucracy. So we’re looking here at the sort of organization of designers in the federal government through the New Deal, with some lingering sort of vestigial components still remaining in places like the EPA, the Army Corps, the BLM; some of our actual worst actors in the federal government, where we still have designers and planners employed.

And I think it’s becoming more widely understood that the New Deal itself was not a single piece of legislation or even a package of legislation but a descriptor for an era of policy making? Which is again I think how the Green New Deal is now becoming more commonly understood. It was initially sort of canceled by people for HR 109 not being a serious piece of legislation; people who didn’t understand it was intended as a set of goals and frameworks. And if we look at the sort of—the why and the how of how the New Deal itself came together we can look at three overlapping crises that produced the space for it to occur.

One of them was their own ecological crisis, the Dust Bowl and the forced migration of three and a half million or so people from the Midwest, mostly to California. The second was the sort of massive global financial crisis of the Great Depression, which brought us to about 20, 22% unemployment in this country and gave us the politics space for something like a jobs guarantee and the CCC and WPA in other places. And the third was the rise of global fascism. And the political crisis that forced FDR and his colleagues to the table to offer an alternative.

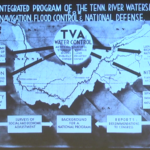

Though those are important?, I don’t want to spend too much time in this talk on the sort of well-known stories. I know other people will probably do that or we can have that in the conversation. The TVA, the CCC, the WPA—we’re looking just quickly at some of the TVA’s images here—in part because I know other people will cover them but also in part because those agencies are often held up as exemplars and they’re actually quite dangerous for us to think about in this context? The TVA itself was a very anti-democratic centralized planning institution. Its board is comprised of people appointed by elected officials in the region it covers. Almost all of whom are funded by the coal and fossil fuel industry. And so it shouldn’t be a big surprise when the TVA’s fuel mix turns out to be much more reliant on coal than the median utility in this country. It’s because the people who appoint the folks who sit on the board make their living raising money from the coal and fossil fuel industry?

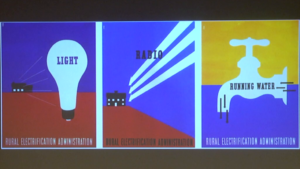

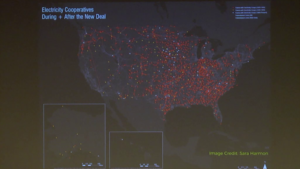

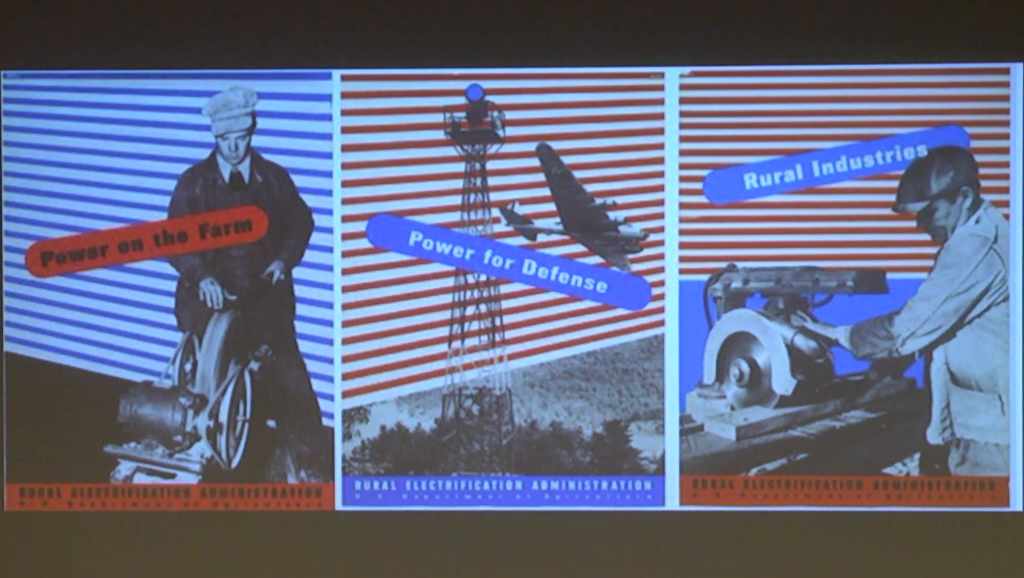

There’s actually far more I think in there for us to learn from places like the REA, the Rural Electrification Administration. One that built some 380,000 miles of transmission line over the course of the New Deal. That’s about 42% of all the lines ever built in this country. And in a few short decades, less than the time scale we’ve been handed to decarbonize our economy now, they were able to raise rural electrification rates from 10 to 97%, and did it mostly through cooperatively and publicly-owned utilities, many of which still exist today. And we’re looking at a map here from one of my grad students who I think is not here, Sara Harman, just showing literally a footprint of the REA over the course of the New Deal, the places where it stood up coops, where it built transmission lines, where it did all of the work I just sort of described to you.

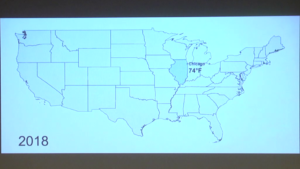

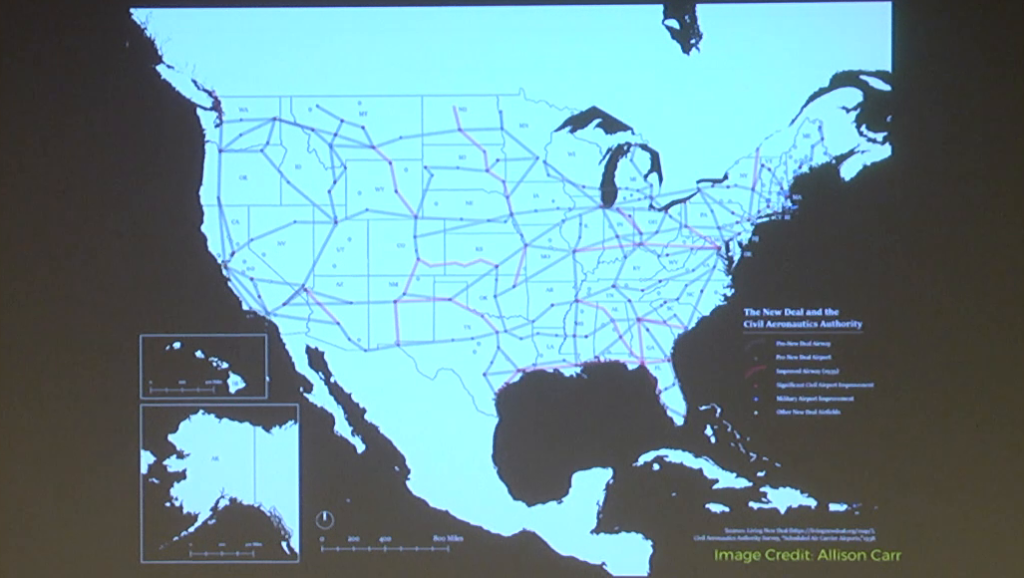

We might also look at a place like the Civilian Aeronautics Authority, an agency that gave us our network of municipal airports and all of the weird pre-radar sort of way-finding devices that we still have scattered across the landscape. These are like literally large arrows drawn and built into the landscape for planes to follow. And for folks who’ve flown to Chicago you recognize this probably. This is Midway, most of our municipal airports can trace their roots back to the New Deal.

And we’re looking here— I think Allison is here? Carr? Are you here somewhere? Yeah, she’s back there. So this is her map, another one of my students. We’re working on a Green New Deal studio together this semester. And so if you look again these are places with a very high carbon legacy. These aren’t things we wouldn’t necessarily want to replicate exactly as we find them today? But they’re nevertheless I think an example of what we can point back to when we’re told that the hollowed-out government we’ve designed for ourselves can’t do anything big anymore. Of course it can’t, we built it that way. But that hasn’t always been true, and design has not always been weaponized in the way it’s been weaponized in this particular moment.

And so as we think about what our sort of generational projects might be, and what ambitions we might take from the New Deal, and we think about their overlapping crises…we think about the moment we find ourselves in now with our own ecological crises. This one, that of global climate change, our own financial crisis, part of it stemming from the Great Recession. But also the sort of continuation of downward mobility amongst rising generations in this country and around the world. And our own, again, political crisis with the rise of not only global fascism but fascism here at home.

The Public Works, Nancy Levinson

It seems increasingly clear, at least it did a few years ago when Nancy Levinson from Places offered this to us in one for many amazing essays on the topic, that as we look ahead to the Green New Deal, it seemed at the time anyway (this is 2012, I believe) that the Great Recession is not sparking a New New Deal. We didn’t yet have the language of the Green New Deal. And that if we confront this crisis and our political climate, at the moment anyway that she was imagining this, we seemed very contemptuous to the very idea of the public. So a lot has changed in a few short years.

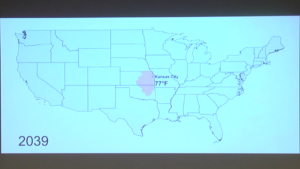

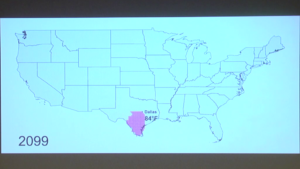

And if we think about how we’ll… We’re looking at Chicago’s temperature profile over the course of the next century here. I think the big questions I have about the Green New Deal that we’re trying to work through now fall into sort of two categories.

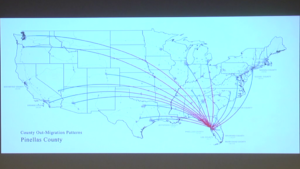

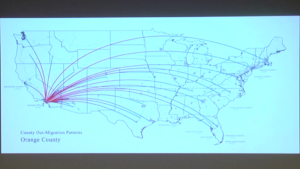

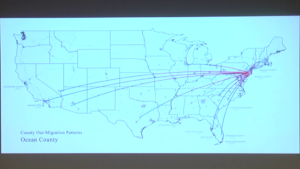

One is, how are we going to balance the need to build the most stuff we’ve ever built, as fast and as well as we’ve ever built it, with our desire to uphold this country’s democratic values and self-determination? We’re looking here at migration patterns projected from sea level rise and climate change, and this is where they’re going to move. This is Mat Hauer’s work at the University of Georgia that we visualized for him.

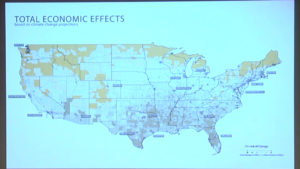

And we’re looking here at just…on top of those climate refugees adding 100 million people to the US, which is the sort of median projection for the next fifty years or so, what that would look like building at these different densities.

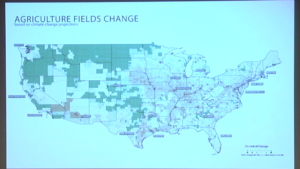

The second question is how we think about growing our coalition beyond rooms like this, beyond places like Philadelphia and Providence and New York and Boston. I’m from rural Arkansas so I think a lot about places like that, and in our studio we’re looking at places like Appalachia, the lower Mississippi Delta, and the Corn Belt in the Midwest in part because we know we can’t actually achieve any of the goals of the Green New Deal without putting those places if not first then very close to first? And we also probably cannot grow our coalition large enough to achieve all the things we want to achieve without bringing more and more people along.

And I’ll zoom through those pretty quickly.

And so let me begin to kind of wrap up here by connecting the dots between the New Deal, the Green New Deal, and the sort of political train we now find ourselves in. And to the former the point, you know those of us at places like RISD and Harvard and Penn, in particular, with resources and power at our disposal—this is with what Damian was just talking about—have to begin to organize our colleagues, too, not just to allow ourselves to be organized by the movements we’re hoping to serve but to organize our colleagues around these ideas. To do more than to give out a practice that simply blunts the worst effects of climate change, produces striking visuals and the like. We have to begin the offer on-ramps from our places into movements, to create space for climate action and climate activists to be welcome and part of our schools. And for us to find ways to move together to build this anti-capitalist counter-hegemonic bloc that is going to determine whether or not we succeed on this Green New Deal terrain.

And what I’ll say— I know I’m like, running out of time, I’m going to be very very quick. Damian asked me to talk a little bit too about this sort of like ongoing fight I’ve had with Shawn Kelly and ASLA, which I’ll do really quickly. Shawn is thankfully no longer president at ASLA so…goodbye?

But anyone who was in Atlantic City with me last…February, January, might remember I gave a presentation about a book we’ve just put out called Design with Nature Now. Very benign presentation. About an hour. The last three minutes or so, I put up a slide showing a AIA’s very like, timid endorsement of the Green New Deal, HR 109, and sort of asking people in the audience to email, call, whatever ASLA’s office and ask them to make a similar statement, or maybe a better one, God forbid.

And I did not know at the time, but Shawn Kelly was in the audience. He was extremely not happy with me. Went to the stage the next day, in theory to give a talk and used that entire talk to talk about why they would not be endorsing…not the Green New Deal because he didn’t know the name of it, but that green plan? So he also I think sided with Nancy Pelosi on that.

And eventually they felt compelled to put out a statement around the Green New Deal, HR 109. Which is, if you read it it’s probably the worst statement I’ve ever read on any piece of legislation. It made everyone mad, it did not endorse it, it did not attack it, so everyone from every side was mad with them. And for us then… Aside from picking a fight with the ASLA president which maybe was not the smartest thing I’ve ever done, it really set us into action and then to work I think within the Center to think about pressing them on this issue in a variety of ways.

So, one of those was to pull together this event that Damian’s mentioned, Designing a Green New Deal in September. This is Varshini Prakash leading a bunch of stiff designers in song. You can see like, this is one of the most insane pictures for people who know designers to ever look at. You have Marilyn Taylor who was our former dean and like very into corporate architecture next to Naomi Klein, next to Raj Patel, next to Alyssa and Thea and like DSA Ecosocialist Caucus over here in the center. I don’t know if she knew who all these people were, but this is an insane picture to think that I have now.

And then this event and many other things got us to work on helping to write what became the Green New Deal for Public Housing bill that AOC and Bernie just put out for the Homes Guarantee bill, the Homes for All Act that Ilhan Omar just put out. And the formation of this sort of student-led group. Let me zip through these really quickly. Those are just some of the Data for Progress things you can always look at if you have not already.

It also led to the creation of this really amazing group of students who’ve been agitating ASLA for the last few months as well called ASLA Adapt and who then I think along with us and all of this other outside pressure we built on ASLA, sort of forced them to the table to put out this statement around the Green New Deal for Public Housing bill that just came out a couple weeks ago, where they actually endorsed it. Part of that is that Shawn’s…no longer the president, and the CEO at the time is no longer there. But also because of all of this outside pressure that had bent ASLA into this coalition in ways that I did not expect to happen quite so quickly. And that has I think helped us think about how this work might continue going forward as we think about the other aspects of the built environment in a Green New Deal that we’re gonna take on in the Center and as a set of fields.

And so I just want to end here—I promise I’m done—by just acknowledging my students who are here today. Can you all like, raise your hands. I see some of you in the back. This is also my way of keeping attendance. There’s absolutely nothing in this presentation that I think would’ve come together for me as clearly or as quickly—and it’s like, I think we’re supposed to be ten and probably really fifteen minutes—if not for the work they’ve been doing with us this semester. They’ve done really incredible things helping me think about the Green New Deal an the built environment. And so I wanna think Damian and thank them for having me here.

Further Reference

Climate Futures II event page