My topic, as Paolo said, seeking personal truth, really builds on the back of much of what we have heard already this morning around the challenges of changing times, changing technologies, changing language, changing expectations.

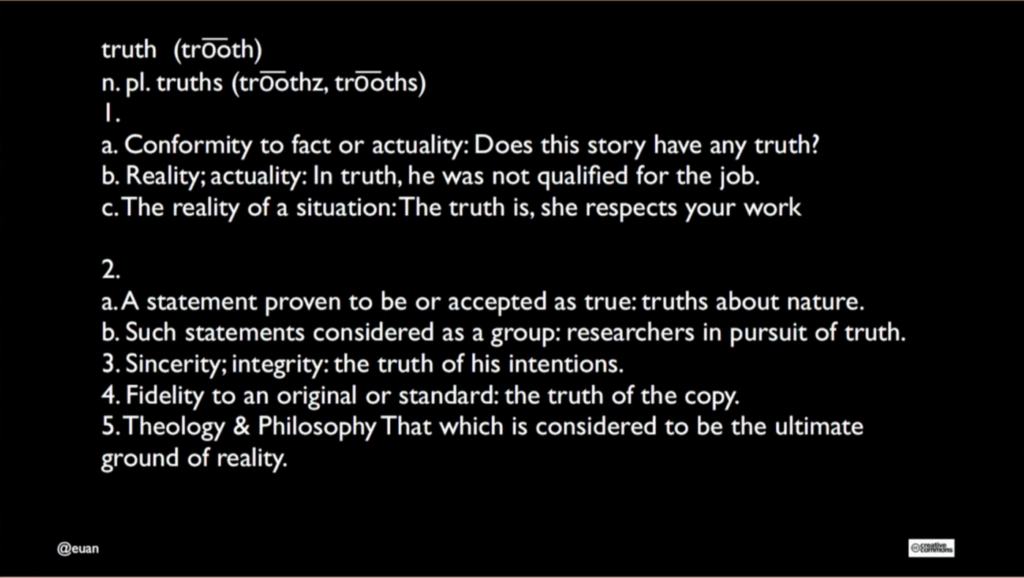

And I thought I would look up the word truth. And I thought it was interesting that there were eight different definitions of the word truth. And even the fact I’m using the word truth rather than fact—because being grammatically pedantic it occurred to me that you can have correct facts and incorrect facts. Which is odd. But I think we are groping towards this idea of truth. And even the word truth can be defined in multiple different ways. So we are by its very nature dealing with a very slippery topic.

And I discovered just how slippery when I did two stints of jury duty in the United Kingdom. It’s unusual—most people are asked to do it once. For some reason I had to do it twice. And the first time was a young lad who had been accused of sticking a beer glass into somebody’s face. And he was a rough lad. He looked “stereotypically” like somebody who you could imagine doing that. But nobody had actually seen him doing that.

So when we got into the jury room, if any of you have seen 12 Angry Men with Henry Fonda, I ended up being Henry Fonda. Because everybody else just said, “Well, of course he did it.” Well I had to keep saying no, nobody saw him. There’s no evidence. We’re here to assume innocent until proven guilty. And the case ended up being thrown out. And they had to start again. So I came away from that very disillusioned about the jury system and the imprecision of it as I saw it, and the fact that there was no way I ever wanted to be on the receiving end of that process.

The second time, there were two cases. One was again a young man who was meant to have beaten somebody up in a pub fight. Differently this time, there were many people who had seen and it was pretty obvious what had happened. And we found him guilty. And the second case was somebody who supposedly had been involved in a fight, but it turned out to be a business competitor trying to discredit him.

In that second circumstance I felt more comfortable that we had got to the truth in both of those cases. But we got there by a very roundabout, imprecise, way. And each of the witnesses, who offered very confidently their truth, actually saw very different things. And there are so many scientific studies of just how subjective, even in really critical situations, our sense of the truth is.

And that’s partly contextual, to go back to Massimo’s point this morning. So much of our sense of truth is down to context. And we get that context from our society, our parents, how we grew up, how we observe the world around us as we grow up, which is our culture. Culture partly being mediated and propagated by the media. And we had a discussion this morning and over lunch around the role of the media and whether it does or doesn’t help us get to the truth.

We have set up and supported and trusted institutions to validate the truth, to accredit things, to license things, to verify things. And have trusted those institutions to tell us the truth. And all of this based on authority, which again came up in some of the conversations this morning. We have conferred authority on those institutions, and individuals who work in those institutions.

Another aspect of the context is how we make sense of the world. And some of you if you’ve been at these events before will have heard me discussing or comparing the impact of the Internet with the impact of the printing press. And how prior to the printing press the Medieval church were the custodians of the truth—that was the one version of the truth. They owned all the manuscripts, they wrote all the manuscripts. It was a very formalized, rigid structure. And then the printing press weakened that. And our ability to write and tell and share stories eventually led to the reformation of the church, and England, and the Enlightenment, and our modern scientific worldview partly at least arguably came out of that step change.

With the Internet I think we’re going through another similarly significant challenge, period of change. Now, in that context we have to make sense of our lives through stories—through big stories. And this is about…thinking back to pre First World War, where the church and the state had been around, stable, trusted—a relatively safe, predictable world. And then Charles Darwin and the First World War trenches blew holes in those two sets of stories. People became less confident, less trusting of those big stories.

And then between the wars, you had the two isms, fascism and communism, as the big pseudoreligious, sensemaking, contextualizing stories that stabilized—people thought that was the way the world was. And then the Second World War blew holes in those two stories. And subsequently both of those ways of looking at the world have diminished and retired to some extent.

And then they were replaced, for most of us in the West, with consumerism. Buy stuff till you die has been the predominant story. Get a good job, make enough money to buy things, do that for long enough until you can retire and buy a fancy holiday has being the main motivation for many of us in our lives. And I think we’re running out of that story. That story does not work. It’s not making us happy. It’s not giving us answers. And I think we’re feeling unsettled because of that absence of big sensemaking stories. We’re sort of making it up as we go along.

And along comes the Internet, which speeds things up. It exacerbates things. It amplifies things. It amplifies truth, it amplifies mystery. It speeds up the speed at which information is coming to us. It amplifies all the consequences of that unease that we were feeling.

And it is very malleable. In that world the truth is very…fragile. Anybody with a loud enough voice or a big enough following, or who’ve paid enough PR and marketing people—whatever—can dominate the sense of truth. Partly because we have been trained through the previous story about buying stuff till we die to be mostly passive consumers. We’re used to waiting for people to tell us the truth. It’s easier.

Somebody said the other day that it was easier in the old days when the news told us the truth. We haven’t had that for a long time. You end up in a sort of relativistic mush, as I call it, where anything can be true. We don’t know how to grope our way towards absolute truth. We were talking over lunch about science, and even many scientific facts don’t last very long. In fact, the power of science is that it’s constantly questioning its own facts. And if you just look at the polarity between whether sugar’s good for your or fat’s good for you that’s going on at the moment, which of those are truths?

But more positively, back to some of the comments again that we had this morning, there is the possibility of greater transparency. I’ve already forgotten the speaker’s name that was talking about the freedom of information and the fact that more facts are potentially more visible to the citizenry to make better judgments about those in authority. And we’ve all seen the fact that we all have broadcast devices in our pockets that [are] making it possible—not inevitable but possible—for the truth, the ephemeral current truth to be made visible to lots of people very quickly. It’s very hard for the official world to stop people filming a policeman killing somebody in a car.

So the tendency is there to transparency. And it is really challenging us in terms of trust, and who we trust and why we trust them. And you notice that I’ve said who and why rather than not what we trust. Because I think it is about what the source of information is, who we confer authority to, that is the basis of trust. And again our unease is we’re confused about who to trust.

And you get challenging circumstances like WikiLeaks, and Edward Snowden. I’ll come to ISIS in a moment. But I put my hand in my pocket and paid modest amounts of money to support the legal support for both of those. And looking back at Assange particularly, you can be very very questioning of his motives. But at the time I felt it was a strong statement, a brave statement, about the reality that we’re walking ourselves into, asleep. So he was just pitching out there that these are… As more and more of our data becomes visible, more and more of our data’s collected. Governments and other groups, commercial groups, know more about us than they ever have before. And we don’t always know that. We don’t always realize that. So people being brave enough to stand up say, “No, this is happening,” as Snowden did, I think are important at least in the short term.

And then with ISIS, you know, it’s probably too current to get away with the old saying of one man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter. But it is really interesting how they are managing in their communities and their networks to be appearing to tell the truth to enough people to cause the massive resources of the Western world to feel significantly challenged and afraid, whether it is factually true or not.

So in a sense all three of these I think are just symptoms or significant aspects of the power that’s beginning to head our way, as is Trump. Actually, before I go into Trump, just to go back to Brexit. I mean, it was really interesting just watching the badly-informed debates. And trying to work out what was actually happening even through the formal news media was really hard. And I went to bed the night before thinking, “It’ll be alright. There’s now way.” And then woke up the next morning obviously thinking, “Bugger. They’ve done it.”

And I really really worry that we’re heading towards a similar sort of scenario with Trump, where enough Midwestern Americans or die-hard Republicans or whatever are almost not caring that he’s not telling the truth. You know, some of the stuff is so extreme that truth almost doesn’t come into it. It’s just wish fulfillment. It’s fantasy, it’s a narrative. And of course it’s happening because enough people are taking at face value, or responding positively, or confirmation bias that we heard about earlier, the sort of stuff that’s coming from the Trump camp.

And we’ve also heard this morning about the fact that volume is a significant challenge. Just trying to work out from the massive number of sources that we’re faced with, the massive amount of noise that we’re faced with, what is actually signal. What is worth paying attention to. Clay Shirky talks about attention deficit. We only have so much attention we can pay to things. And part of the reason that Trump and others have as much impact as they do is because we’re tired. We’ve sort of given up trying to work out what the truth is because it feels too hard, and trying to hear the signal for the noise is just too hard.

But I think it’s literally in our own hands, increasingly. In the sense that we have these devices, which we are in control of, no matter what Facebook or others try to do with them. We choose when we turn them on, we choose when we turn them off. We choose what we look at. And there’s a chapter in my book that I called “We all have a volume control on mob rule.” So we have the opportunity, we have the responsibility, to decide what we pay attention to, what we don’t pay attention. What we amplify and what we don’t amplify. And this comes down to micro decisions of what am I going to like on Facebook? Why am I liking that? What will my network think if I like that? Will they respond? Will they further amplify that? Will I push back against it? Will I argue against it? Will I take on the righteous right or whatever else by sticking my hand up and saying, “No, that’s not true?”

And I think we are all going to have to get better at, braver at, more confident at, exercising that responsibility. Because at the moment the truth flurries around on the Internet like shoals of fish, and we don’t know where it’s going to land. So, again back to what Massimo was saying, I understand the fears, I’ve obviously talked about some of the risks. I think the risks are real, pertinent, current, and significant. But equally, you get nothing without taking a risk. And I do also feel that we are in the period where you have enormous opportunities to do things differently. To reinvent our institutions. To reinvent the practices and processes and laws that make things turn out well rather than badly. And we need to get better and faster at doing that.

Now, again we’ve been talking over the last couple of days about the need to slow down, and the fact that many early adopters like Paolo and myself have just spent so long with so much passing through our heads, with so much information, that you realize you just need to get better at shutting it up, and getting it to stop, and giving your head the room to recover and to think. So there’s a whole industry around mindfulness and meditation and sort of techniques and ways of looking at the world that just help you to distance yourself and step back from the buffeting that we’re all beginning to suffer from. So for instance I climb mountains and go for long walks, partly just to force myself to get away from the constant connectedness.

This is a word that gets misused and overused, and certainly back in the early days of blogging it was a significant aspect of what we were trying to do. But again, this is an opportunity. Having been mindful, having been more thoughtful, having slowed things down more, that whole thing about saying what you actually think, being authentic, saying clearly and as understandably as you can your interpretation of the world around you and being prepared to stand by it. Being willing to stick it out there, open it to disagreement, opening yourself to the consequences.

I mean, I’ve told the story before, but this is why I called my own weblog “The Obvious?” Because it was me overcoming my reticence about stating the obvious. I would think, “Well everybody knows this. It’s patently obvious.” Or they might disagree with me or whatever. But after fifteen or sixteen years I’ve learned that actually what I have seen and what I’ve understood, the way I perceive the world, isn’t necessarily obvious to everybody. And once you’re brave enough to open up and share some of that, amazing things happen, taking the consequences. And that takes courage.

And I think it’s courage that we’re not used to exercising, again going back to being trained to be conforming, passive, safe. This is one of the biggest challenges working with large corporations, where I’m extolling the virtues of having these networks internally. People are terrified of losing their jobs. They’re terrified of sticking their head above the parapet or being the tall poppy that gets chopped down. It takes real courage in those contexts to say what you think. And this idea is a book called Radical Honesty, that if we are heading towards transparency, if trying to hide and dissemble is increasingly a non-starter, being as honest as you can be as quickly as you can be in many ways is the best defense policy. So, more open, more transparent, more honest, earlier, in some ways is the best way to stay safe.

And that whole thing about being open and honest, especially in the UK, we’re quite resistant to that. I remember an older relative of mine saying, “Oh yes, blogging. That’s just people sharing their opinions.” Yes. What’s so wrong with people sharing their opinions? And still they said well, who are you to think that, or who are you to say that? Or you are self-obsessed, you are narcissistic. We even accused journalists of being narcissistic this morning.

But my older daughter Mollie, who’s blogging and I’ll show you her blog in a moment, responded to the thing about selfies and how Middle East folks who don’t take selfies dismiss it as young folks nowadays being narcissistic. And Mollie actually flipped it and said no, it’s more about being brave. It’s about desiring to connect with other people, being vulnerable. So there’s a whole fashion of—I can’t remember what they call this, like “naked selfies” or something, where they don’t wear makeup. Where it’s just them as they see themselves in the morning when they wake up. So a bit more back to again what Massimo was saying with the videos. It’s people choosing to be quite radically, to many of us uncomfortably, open in a very direct and intimate way. So rather than projecting inwards the image in the water of narcissism or projecting a particularly airbrushed vision of yourself out, it’s actually more about a vulnerability than it is about dominance.

Writing ourselves into existence.

David Weinberger [presentation slide]

And again, I’ve quoted this before, but this is a phrase from David Weinberger when he was talking about blogging. But I think it now… You know, the activity of blogging, if you like, has morphed into other platforms and other things. But this ability to as he described it writing ourselves into existence.

So for instance, I not only have my blog but I journal, and I carry Field Notes notebooks and pencils. And I’m just constantly scribbling stuff down that I’ve noticed, that I’ve thought, that piqued my interest. And in doing that I become more aware. I become more noticing of what’s happening around and perhaps what it means. And if I then choose to share that on Twitter, Facebook, Snapchat, whatever, I’m projecting and I’m pushing it out into my network. And then I get to see what reaction that gets.

And again, counter to some of the ideas that have been expressed this morning, it’s not just seeking approval. I’m never happier than when somebody comes back with a thoughtful, sincerely-conveyed rebuttal that says, “Mmm, you know. I don’t agree. I think there’s this difference. There’s this nuance that you’ve missed.” And over the years I’ve learned to appreciate that and to respond to that, and think okay, do I care? Do I still think I’m right? Will I adjust?

So again, back to that volume control on mob rule, I’m making microadjustments. Trying to—within the context of my ego’s willingness to be right all the time, whatever else—trying to adjust what I think is true. And if I’ve done a decent job of pushing it out into the network. Not as a professional journalist, not a story teller, but just as somebody who’s gone, “Oh, that’s interesting.” If I’ve done that well other people go, “That is interesting. I didn’t know that.” Or, “I’m glad somebody else has said that. I’ve thought it for ages and I’ve never shared it with anybody.” So it’s like throwing pebbles into a pond. And you get better at throwing bigger pebbles into better ponds and causing bigger ripples.

And I mentioned Mollie’s blog, and she’s she’s been blogging for a couple of years now. And she’s just gone up to university at Cambridge to study English literature. And she has over the years suffered significantly from anxiety, to the extent that it made her physically ill. When she was nine or ten she had ME and had to be off school for about a year. And when she went up to Cambridge, she was scared, and she became physically sick, headaches or stomachs. Penny my wife had to go and stay with her over the weekend.

And then Mollie’s written a couple of blog posts about that. The second one was more vulnerable than the first, and she sent it to me in advanced and said, “Am I oversharing, dad? Is this too much?” Asking me just to check the motivation, if you like. So to some extent, to some people, that might have felt like oversharing. Like being vulnerable, like taking a risk. But boy did she get a positive response. She had lots of people coming out of the woodwork who she’d never met yet at university saying, “I’m so glad you wrote that. I feel the same.” Other people offering help, whatever. And this extended her network exponentially. And I think that to me is the opportunity, is that fact that we have this opportunity to think harder, share better, respond to what we’re sharing. And out of that to begin to build the fabric of society.

Now, we will get hurt. People won’t always agree. People will not understand. And again, there was a risk involved in this that she could have been vilified for it. Getting better at being brave on a more regular, ongoing basis I think is key. But actually again as has been said this morning, being human… Now, I think we’re going to hear from a later speaker around technology and AI and all the amazing stuff that’s becoming possible. And in some of my talks that I do with corporations I call my presentation “Staying Ahead of the Robots.” That if technology is going to eat away at the lower end of routine bureaucratic, financial, legal, medical work, how are you going to add value? How are you going to differentiate yourself above what could be done by a robot? It’s by being more human. And being human means being fallible, means being scared, being brave.

…the more people are trained to think in terms of moralistic judgements that imply wrongness and badness, the more they are being trained to look outside themselves—to outside authorities—for the definition of what constitutes right, wrong, good, and bad. When we are in contact with our feelings and needs, we humans no longer make good slaves and underlings.

Marshall B. Rosenberg, Nonviolent Communication: A Language of Life [presentation slide]

Now, having expressed concerns about relativism, and clearly there are things that we need to get to some kind of consensus about right and wrong, this was really interesting. Our willingness to be in an ongoing position of working things out I think is going to increasingly be a key skill. Being less hung up about getting to a right answer and being more tolerant of ambiguity.

The other thing is that we’ve been so seduced into thinking that our brains are the most important parts of our bodies to the denigration of the rest of it, we’re this bit of meat between our ears lumbered with this rest of our body. But neuroscience is showing us that we have as many neurons in our stomachs and our hearts as we do in our heads.

We know the truth not only by reason but also by heart

Blaise Pascal [presentation slide]

And the whole language of gut feelings, broken hearts… You know, we do respond to the world with a whole complex system, not just the analytical, reductionist, language-based bit of meat between our ears. So again, celebrating that humanness and that mixed set of triggers and responses.

And just a last couple of thoughts. I think we are increasingly faced with ephemeral truth. Truths don’t stay true for very long. Our perception of what’s true doesn’t stay fixed for very long, and as I said that is a disconcerting, challenging, environment. But equally, we all know the big, eternal truths. The sort of truths that the various religions over the years have sort of hijacked and sold back to us. We know, mostly, what being kind means. We know what causes harm to other people. We know what makes us happy if we stop long enough to think of it.

If you have the choice of being right or being kind, be kind.

Wayne Dyer [presentation slide]

And I’ve always enjoyed this quote from Wayne Dyer. And I think as we move into a more challenging and ephemeral and volatile world of truth, being less hung up about being right and more aware of the need to be kind. Thank you very much.